Trapped in collective memory

The Battle of Warsaw, commonly known as the Miracle on the Vistula and associated mainly with the date of August 15, 1920, led to the end of the Polish-Soviet war and the signing of the Treaty of Riga in March 1921. In Riga, the shape of the eastern border of the Second Polish Republic was decided upon, and consequently also the fate of 1.2 to 2 million Poles (depending on estimates) living in the eastern territories of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which were not included in the reborn Poland. Some of the Poles living after 1921 in the territory of the Soviet state and formally subject to the local authorities became victims of the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD in 1937-1938.

Not everyone realizes that not only the term "Miracle on the Vistula," but also "Battle of Warsaw" is a metaphor. I mention this issue to draw attention to the fact that what we remember and how we remember is, to some extent, only an illusion of the past reality, co-created by all participants in the historical discourse, and - above all - by the people and institutions that set the tone for the discourse.

After all, the Battle of Warsaw did not take place only on the outskirts of Warsaw, but on a much larger territory, reaching as far as Białystok at one point, and August 15 was not crucial for the fate of a number of military operations taking place on August 13–25, which were given over time the name of Battle of Warsaw. The term "Miracle on the Vistula" is a reference to the French "Miracle on the Marne" (1914), and the fact that August 15 marks the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Catholic Church contributed to the dissemination of this expression and the association of one of the greatest victories of the Polish army with the miraculous intervention of the Mother of God. The state also contributed to the process of creating the historical memory of Poles in the field of the Battle of Warsaw, establishing first the Soldier's Day, and then the Day of the Polish Army on September 15.

The content of history textbooks and museum halls, as well as the order of public holidays, are a construction designed to help society organize and understand its own past. This does not mean, however, that events of interest to the collective memory of a given group are objectively more important and significant than those that the group does not remember for various reasons. This applies, for example, to the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD in 1937-1938, which is not talked about much in Poland, and which was an event no less important and no less worth commemorating than the Katyn massacre or the Volhynia massacre.

"The Polish Operation" of the NKVD

The "Polish operation" of the NKVD began on August 11, 1937 on the basis of order No. 00485 issued by the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs Nikolai Yezhov, then approved by Joseph Stalin himself. As a result of the criminal activities of the Soviets, at least 139,835 people were subjected to repressions, of which no less than 111,091 were murdered - most often with a shot to the back of the head.

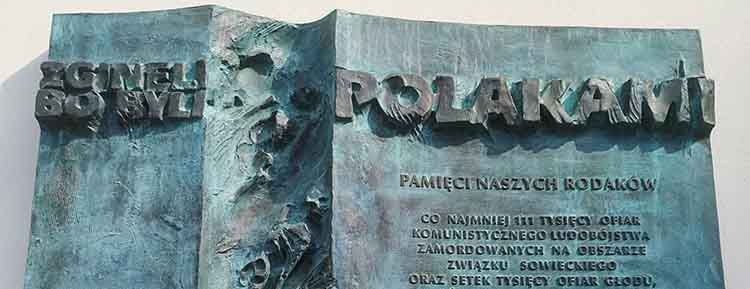

Plaque commemorating the "Polish operation" of the NKVD in Krakow - photo August 11, 2020 (Source: DlaPolonij.pl)

The “Polish operation” was carried out under the accusation that its future victims allegedly belonged to the Polish Military Organization (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, POW), which was supposed to conduct espionage and subversive activities in the USSR for Poland. Document No. 00485 stated that: “(…) work on liquidating local Polish sabotage and espionage groups and POW organizations is not fully developed. Both the pace and the scale of the investigation are extremely inadequate." The task of the NKVD was to correct this error.

In fact, there was no Polish Military Organization at that time that would carry out “espionage and subversive” activities in the USSR. The Soviets wanted to force the Poles to submit because they strongly resisted the state-imposed collectivization and atheization. It was also feared that in the impending war with the West, the Polish population would be a potential support for the enemy. Terror, intimidation, and brute force were the methods the Soviets considered most effective. They chose to use them in this case as well.

According to Order No. 00485, the following were arrested:

- Activists of the Polish Military Organization discovered during the investigation and not yet found.

- All Polish prisoners of war remaining in the USSR.

- Fugitives from Poland, regardless of the time of their transfer to the USSR.

- Political emigrants and persons coming from the exchange of political prisoners from Poland.

- Former members of the PPS and "other Polish anti-Soviet political parties".

- "The most active part of the local anti-Soviet nationalist element" from Polish national regions.

Hence, the social or economic status did not matter. Only "anti-Sovietness" that was directly related to Polishness mattered in the order.

The "Polish Operation" was not the only nationalist action carried out in the USSR. However, it was distinguished from the others by the exceptional scale of repression and the brutality of the methods used. On August 15, Nikolai Yezhov issued order No. 00486. Under this document, not only "traitors to the homeland", but also their families were subjected to repression. As a consequence, the relatives of those murdered by the NKVD were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan, and often also locked up in gulags.

The vast majority of the victims of the "Polish Operation" were Poles. Among the murdered and repressed, however, there were also Ukrainians, Belarusians, Jews, representatives of other ethnic and national groups living in the USSR, as well as the Russians themselves. The genocidal action of the NKVD ended with order No. 00762 of November 26, 1938, signed by Lavrentiy Beria. It was preceded by a directive issued on November 17 by the Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party (BCP) and the Council of People's Commissars to suspend the operation of special judicial bodies and to end mass operations. As written in the order:

The resolution of the SNK of the USSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (b) of November 17, 1938 (...) exposes serious irregularities and distortions in the work of the NKVD and the prosecutor's office and indicates the ways of improving the activities of our Soviet intelligence regarding the final defeat of the people's enemies and purging our state of espionage subversive agents of foreign intelligence and all traitors and traitors to the homeland. (…) The organs of the NKVD, consistently implementing the resolution (…) of November 17, 1938, under the leadership of the Party and the government, should quickly and decisively eliminate all errors and distortions in their work and thoroughly improve the organization of further struggle for the complete destruction of all enemies of the people, for purging our homeland of the spy and subversive agency of foreign intelligence services, thus securing further achievements of socialist construction.

The number of more than 111,000 human deaths, therefore, is a "serious irregularity, error and distortion" in the work of the NKVD officers and the prosecutor's office. In the near future, the Soviet authorities will use the same moniker to refer to the rule of the one who headed the state during the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD — this is history's giggle.

At the margins of collective memory

The "Polish operation" of the NKVD — despite the shocking scale of this genocide — was pushed to the margins of collective memory and did not penetrate the consciousness of Poles to a degree similar to the massacre in Volhynia or the Katyn massacre. Although, in the 21st century, a number of scientific papers were devoted to the event, and some institutions, such as the Institute of National Remembrance or the Juliusz Mieroszewski Center for Dialogue, cultivate the memory of it, in the social dimension of historical discourse it is almost absent.

The political situation in Poland in the years 1945–1989 played an important role here. The falsification of history in the People's Republic period, the silencing of Soviet crimes, and the repression of people fighting for the truth undoubtedly contributed to the deepening of the problem. The Great Terror of the 1930s was then presented as a period of "Stalinist distortions", the victims of which were mainly leading representatives of the Bolshevik party or members of the Communist Party of Poland. The millions of other victims, including over 111,000 murdered during the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD, were not mentioned.

However, this is not the only reason why "The Polish Operation" is practically absent from the collective memory of the Polish society. Prof. Krzysztof Malicki, in the text *The Warsaw Uprising is high in the historical memory of Poles, published, among others, in Kuryer Polski, writes about a specific rivalry between historical events within the memory "market". The researcher points out that, for subjective reasons, we prefer certain events from the past more than others, which makes them much better remembered and seem more important.

I believe that the memory of the "Polish Operation" was drowned in the sea of blood spilled during World War II and during the Great Terror in the USSR. It was overshadowed primarily by the Katyn massacre — a mass murder of a similar form (execution by a shot in the back of the head), also carried out by the NKVD, which took place only two and a half years after Yezhov signed order No. 00485. The events of 1937–1938 were also in the shadow of the Volhynia massacre — another genocide committed against defenseless and innocent people of Polish nationality beyond the eastern border of the Second Polish Republic — and the Great Famine in Ukraine — genocide committed on a massive scale by the state apparatus of the USSR just five years before the order of the "Polish Operation". The memory of Katyn, Volhynia, and the Holodomor was, and is, strong enough so that it even survived the several decades of silence and falsification of history by the communists. The same cannot be said about the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD. Why did this happen?

In my opinion, answers should be sought in the interwar period. The issue of the attitude of the Second Polish Republic towards the Poles who inhabited the territories granted to the Soviets after the Treaty of Riga remains controversial to this day and is the subject of academic debate. There is no doubt that Polish diplomacy in the 1930s was a passive observer of the tragedy of Poles repressed in the USSR. The question of how much this resulted from the lack of real abilities to help them, and how much of it was ignoring - more or less consciously - what was happening in the Soviet Union, remains open. There are also different opinions among historians about the Treaty of Riga itself and the decisions made at that time about the shape of the Polish eastern border, which determined the fate of Poles who found themselves outside of it.

Attributing the blame for the effects of the "Polish Operation" not only to the NKVD officers and the Soviet authorities, but also to the Polish signatories of the Treaty of Riga is definitely too far-reaching and inappropriate. The fact remains, however, that as a result of the decisions taken in March 1921, from 1.2 to 2 million Poles were left without the protection of the Polish state, but under the formal authority of the Soviets. The Treaty of Riga admittedly provided to the people living in the Russian Empire (since 1922, the USSR) the ability to apply for Polish citizenship, and assumed that the Soviet authorities would allow them to go to Poland. However, this required the Soviets to respect the provisions of the treaty. In practice, they did everything to prevent the Poles from returning to the country, and the repatriation operation was completed in June 1924, when, according to the Polish side, there were still about 1.5 million Poles in the USSR. I consider the efforts of the Second Polish Republic to change this state of affairs as far from perfect, even taking into account the fact that the possibilities of the Polish state in this respect, especially in the 1930s, were very limited. In this context, the words of Anna Zechenter are not groundless, as she stated, with a certain amount of exaggeration, that "since before the war everyone was silent about the tragedy of the Poles, which took place nearby, on the other side of the eastern border, it is hardly surprising that it did not survive in the memory of subsequent generations ” (A. Zechenter, What was "The Polish Operation"?).

However, in the process of marginalizing the memory of the "Polish Operation", the policy of the Soviet authorities towards the Polish population living in the USSR remains crucial. On August 15, 1937, Nikolai Yezhov issued the aforementioned order No. 00486 on prosecuting the family members of "traitors to the homeland". As a result, the overwhelming majority of those who, after the fall of communism, could demand justice and commemoration of those murdered during the "Polish Operation", were thrown into gulags or deported deep into the USSR and subjected to forced Sovietization. In the case of the Katyn massacre and the Volhynia massacre, as well as the Holodomor, the situation was different. Prof. Nikolai Ivanov, one of the leading researchers on the "Polish Operation", pointed out that "the victims of Katyn or the Volhynia massacre were commemorated by their families living in Poland, who (…) had the opportunity to speak on their behalf, especially after the fall of communism. Those murdered during the Polish Operation do not have such guardians” (N. Iwanow, The Polish state and the "Polish operation" of the NKVD 1937–1938).

To save from oblivion

The diagnosis by Prof. Nikolai Ivanov is accurate. Therefore, the responsibility for cultivating the memory of the "Polish Operation" rests with state institutions, historians, popularizers of history, and partly also with the rest of society. The victims deserve to be commemorated with a special day of remembrance, to be mentioned at least once a year in the press, radio and television, to discuss their history extensively during history lessons, to devote plays, films, music, and poems to them. There is no reason why the memory of the "Polish Operation" of the NKVD should be less valuable than the memory of the Katyn massacre or the Volhynia massacre.

The "Polish operation" of the NKVD is an unaccounted for crime. There was no full trial of the perpetrators, and no compensation was awarded to the families of the victims. Like Katyn, this genocide reminds us of the civilizational offer Russia brings to Europe, so proudly referring to the traditions of the Soviet Union. Since in the past, the crimes of the Soviet regime remained unpunished, today the citizens of Ukraine experience the continuation of the previously "proven" methods. Remembrance is a necessary means to stop this vicious cycle of hatred and violence, but certainly not the only one.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.