The German aggression against Poland on September 1, 1939, gave the opportunity to implement the criminal plans to another large neighbor of the Second Polish Republic.

The aim of the Soviet invasion of September 17 was not only to take over a specific area, but also to permanently eliminate the leadership layer of the conquered lands. Mayors (pol. starostowie) and former mayors (who hailed from the local landowners and were among local government officials), as well as other professional groups representing the Polish state or constituting local elites, found themselves under a direct threat. It was not, as in the German case, a national on a racial basis, but on the basis of the social class.

It is characteristic that the threat to them was greater than to their colleagues in office in the western voivodeships. There, there was an awareness of the dangers of falling into German hands, and therefore there were evacuation plans. The threat was immediate and therefore it was possible to prepare for it. Hence the so-called plans to withdraw to central and then eastern Poland.

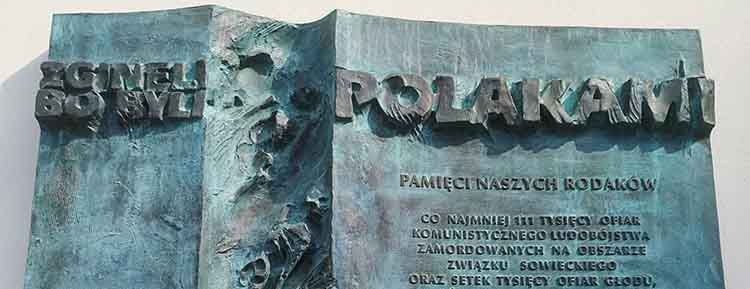

(Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

However, mayors in office in the borderland voivodeships until September 17, 1939, experienced war events only to a moderate extent, and the state administration in this area was still working. Once aggression broke out, the chaos was deepened by Soviet disinformation: the first bits of information claimed that the Soviets were coming to help as allies. As the then deputy voivode of Tarnopol recalled years later, "during these preparations [to hand over the office to the Soviets], Voivode Jarecki from Stanisławów told me by phone that there was no agreement with the Soviets, that they had violated the border themselves and entered a state of war, the attitude is to be the same as to the Germans, and that there is an order to evacuate all mayors." The situation of mayors fleeing from voivodeships located near the German border was particularly difficult. Their status was the same as that of refugees — they were trapped.

As in the case of the Germans, Soviet murders began from the moment the Soviets entered Poland. On September 17, Romuald Jarocki, mayor of Sarny in Volhynia, died at the border. He was shot by the commander of the Soviet patrol. On the same day, the former mayor of Stolin, Henryk Kintopf, who served in the Polesie Voivodeship Office in September 1939, died. Five days later, Jan Płachta, mayor of Złoczów in the Tarnopol Voivodeship, was murdered by the NKVD.

Soviet aggression also opened the way for protests by the local population. After the outbreak of the war, Władysław Staniszewski, a retired mayor of Toruń and Gdynia (he was the initiator of, among other things, paving the road to Kamienna Góra and establishing the Witomin cemetery), evacuated to an estate in Polesie. He was murdered by locals during the demonstrations that took place after the Soviet attack. He was buried on site, in a mass grave.

These crimes, committed "on the spot", in local prisons, with the participation of the Soviet security apparatus, were also committed in the following months. Their victims included, among others: Leon Gutowski, the last mayor of Stolin, and in 1919 co-organizer of the network of the Polish Military Organization in Kaunas Lithuania (for which he was imprisoned twice). At the end of October 1939, Stanisław Harmata died in Lviv, and in the years 1920–1938 he was the mayor of Radomsko, Rohatyn and Stryj. At the turn of 1938 and 1939, he became the head of the voivodeship office in Kraków, and after the outbreak of the war, according to the general pattern, he evacuated east, to Lviv. After September 17, like many others, he found himself in a Soviet trap. Some of those arrested remained in Soviet prisons until the German attack on the Soviet Union and fell victim to the crimes surrounding the evacuation. Wojciech Kostołowski, nominated for the position of a mayor in Bóbrka in August 1939, died on June 26, 1941 as part of the action to liquidate prisoners in Brygidki in Lviv. A long-time mayor, as well as a judge and senator, Tadeusz Giedroyć died in a "death march" after the evacuation of the prison in Minsk.

Generally, those who evacuated to Lithuania in September 1939 were more fortunate. A large part of them got to the West and had a chance to join the Polish Armed Forces. A few, like the last mayor of Stołpce, Stefan Eichler, who were imprisoned in internment camps, were transferred to Soviet camps after the occupation of Lithuania by the Red Army — Eichler found himself in the deserted Kozielsk, from which Polish prisoners of war had been transported to the Katyn forest a few months earlier. He managed to reach Anders's army that was forming.

Marian Wyród-Przyborowski, a former mayor in Brzeziny, and then an inspector at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, responsible for prosecuting abuses in local administration before 1939 (which incidentally caused him to have a nervous breakdown), was not so lucky. Mobilized in September 1939, he found himself in Lithuania, where he was interned. In August 1940, after the Soviet aggression, he was caught while crossing the border. Held in prisons in Marijampolė or Kaunas, sentenced to exile, he was to die in transport in April or May 1941.

Mayors and former mayors fell victim to the genocide that was the Katyn massacre. Its goal was to eliminate the intellectual and political elite of the Second Polish Republic. We can find them in the Katyn pits, but also on the Ukrainian list. Characteristically, until September 1939, many of them managed poviats (counties), e.g. in the Kraków Voivodeship. You can also indicate others who are probably on the Belarusian list that has not yet been found.

Those who were exiled had a certain chance of survival. Some of them will manage to reach Anders and after the war we will find them among emigrants, e.g. in Great Britain. For example, two former mayors and retired generals did not have such an opportunity — legionnaire, founder of the Tatra Volunteer Emergency Service and sailor Mariusz Zaruski and Edward Piotrowski.

During the Soviet occupation, mayors involved in conspiratorial activities also lost their lives. This was a simple consequence of the weakness of underground structures, which were thoroughly penetrated by the Soviets. Their creation on a larger scale was possible from 1941, after the occupier was replaced by a German one. As a result, former mayors operating in the underground (on principles similar to those in the case of the General Government) were subjected to repression during the second Soviet occupation, from 1944.

As in the case of German crimes, only examples of the actions of Berlin's Soviet ally are presented here — actions that were in practice more consistent, murderously effectively eliminating representatives of the Polish intellectual and political elites. Actions whose perpetrators have not been brought to justice to this day.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.