The article originally appeared on the "Teologia Polityczna" website.

The book of prof. Ewa Thompson goes beyond the boundaries of previous research on the phenomenon of yuródivy (юродивый). The researcher confronts the portrait of the saint madman preserved by literature and hagiography with the social and political context of their activities in pre-revolutionary Russia. Thompson argues with the view that the phenomenon of God's madness, booming in Rus and later in Russia until the time of the October Revolution, grew unequivocally out of Christianity. It proves that yuródivy have even more in common with Siberian, Turkish or Finnish shamanism, and their activity is an example of a specific Russian phenomenon, which is bi-faith. Remembering this particular condition of Russian society allows us to come closer to understanding the phenomenon not only of historical, but also of contemporary Russia.

The yuródivy' special place in Russian history is largely overlooked in the West. The holy madmen are little known and not very well understood because they are difficult to fit into the framework of Western social taxonomy. This book is devoted to the analysis of the phenomenon of holy madmen and their largely underappreciated contribution to Russian culture, writes Ewa Thompson in the introduction to the book "Understanding Russia".

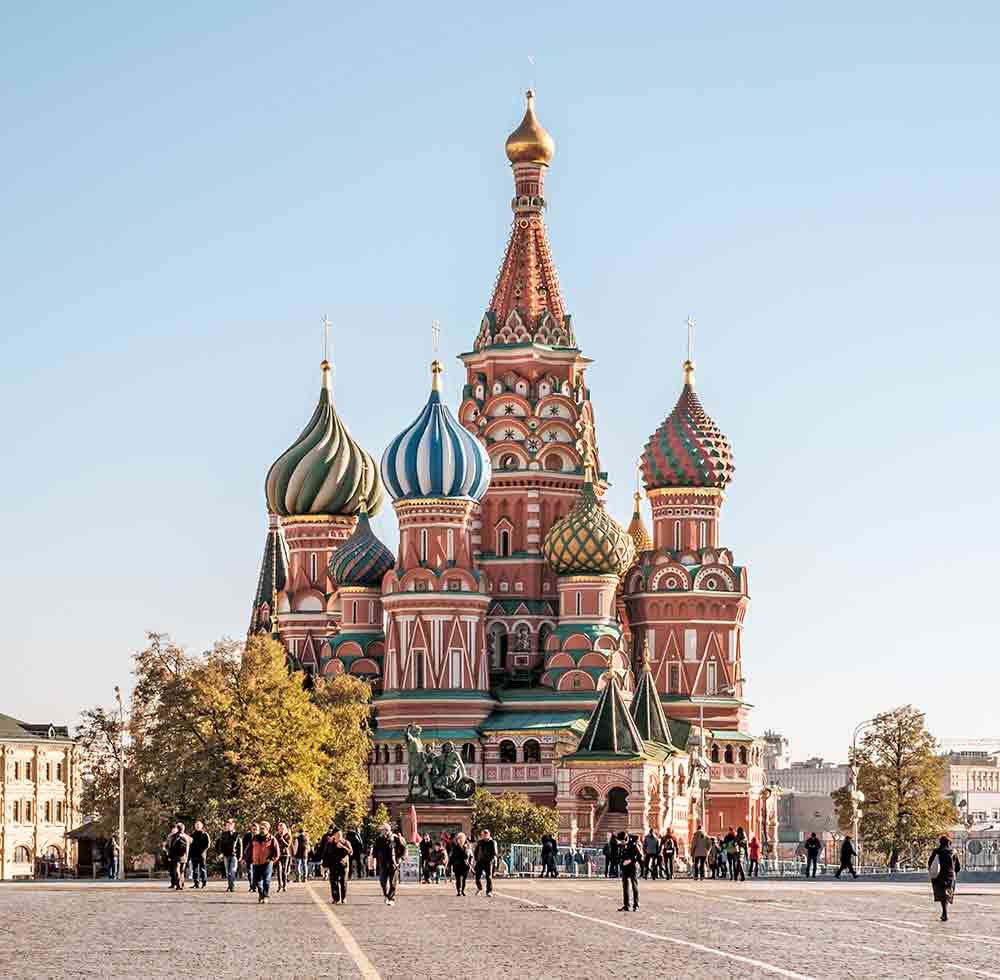

The Intercession Cathedral in Moscow is named after St. Basil (Source: Wkipedia)

On Red Square, right next to the Kremlin, stands the most colorful and famous of the Russian Orthodox churches: Saint Basil's Cathedral (Sobor Vasiliya Blazhénnovo). Its fame and popularity as a Moscow attraction dates back to the 16th century. In 1852, the historian of the Russian Orthodox Church, Alexander Raczyn, wrote: "Of all Russian churches, no one, whether in Russia or abroad, is as famous as the Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed." Rachen's words ring as true today as they did then. This cathedral is still the most famous tourist attraction in Moscow. Its bulbous domes appear on posters, guidebooks, and Russian and foreign books about Russia. They have become a symbol of Russia as much as the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of America.

The worldwide fame of the multicolored domes of Red Square contrasts sharply with how little-known the man to whom this cathedral is dedicated remains. Few people outside of Russia realize that the patron saint of the most famous Russian church is not venerated as a saint anywhere except Russia itself, where he was raised to sanctity in circumstances unclear to this day. Only a few Western Russian history textbooks mention it at all, and those that do, repeat the descriptions found in a Moscow travel guide. Tourists sometimes mistake him for the founder of Orthodox monasticism, St. Basil the Great, but Blessed Vasyliy has little to do with this figure from the 4th century.

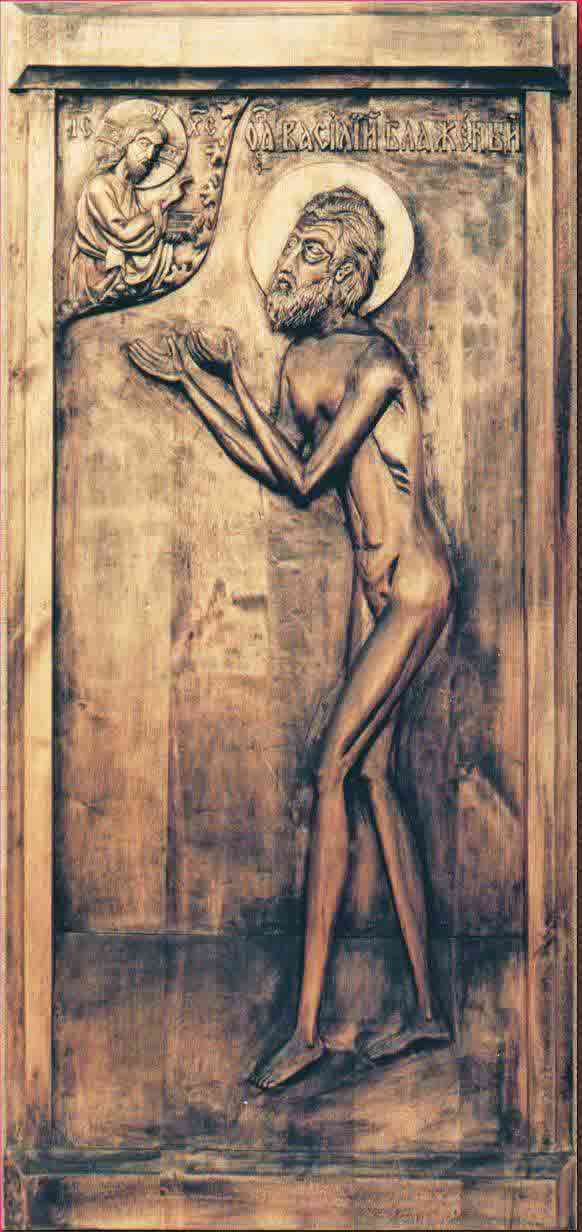

Icon of St. Basil the Blessed (Bas relief, St. Basil's Cathedral, Moscow) (Source: Wkipedia)

Russian St. Basil, i.e. Vasiliy Blazhénniy from Moscow, lived in the times of Ivan the Terrible and was a Moscow patriot. Even in winter, he walked the city streets completely naked. He was credited with such miracles as blinding several girls in the marketplace, then restoring their eyesight, miraculously killing a man who was trying to rob him, and saving Moscow from a Tatar attack. When he died, the metropolitan bishop himself presided over the funeral rites, and Tsar Ivan the Terrible was one of the bearers of the coffin.

Vasiliy, although little is known about him abroad, occupies a significant place in Russian collective memory. He is a figure known in Russian folklore, and the popularity of the church devoted to him proves a deep-seated attachment to the attitudes and values that he symbolized for many generations of Russians. He belongs to the group of people whom the Russians call Fools-for-Christ, or holy madmen, and in shortened form yurodivy. These people were considered holy men, even though they behaved like madmen. They played an important role in the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Russian Empire. According to the public opinion, supported by the statements of some representatives of the Church, they were Christian saints. However, several researchers in Russia and abroad have suggested that the holy madmen were mentally disturbed, or that their worship was a remnant of pagan practices. While they were ignored in official historiography and the press (sometimes by order of censors), Russian literature and folklore presented an idealized image of them in such figures as the holy madman Nikolka from Pushkin's Boris Godunov, or Prince Myshkin from Dostoyevsky's Idiot.

Fool-for-Christ Sitting in the Snow – painting by Vasilij Surikov (1885) (Source: Wkipedia)

Why was this "madness" associated with Christianity? The famous words of St. Paul's statements about being "foolish to Christ" refer to total devotion rather than to imbecility or other forms of mental disturbance. If the holy madmen were sane, why did they behave in such a bizarre manner? If they were mad, why were they honored as Christian saints? The Russians themselves argued over these issues. The October Revolution put an end to these discussions by abolishing all religious worship, including that of holy madmen. Thus, one of the most interesting aspects of religious life in ancient Russia faded from memory. But has it completely disappeared from Russian culture? In my opinion, no.

The yourodivy' special place in Russian history is largely overlooked in the West. The holy madmen are little known and not very well understood because they are difficult to fit into the framework of Western social taxonomy. This book examines the phenomenon of the holy madmen and their largely underappreciated contribution to Russian culture.

When I first became interested in this question, I took the apologists' statements at face value, believing that the holy madmen were the Russian counterparts of St. Francis. As I began reading the compelling and contradictory testimonies about them, I realized that the explanations I had been given before were either incomplete or false. While some of them could probably be legitimized by Christianity, the vast majority of Russian saintly madmen had little to do with Christian holiness. The fact that the legend of their Christian legitimacy had been accepted for so long, and that both Russian (including Soviet) and Western researchers kept coming back to it and presenting it as proven and true, was an additional stimulus for me to undertake polemical research.

In the history of the Russian Church, in the Russian approach to mental illness, and in the tradition of shamanism in Russia, I have found information that contradicts what apologists for holy madness claim. The sources I used included, among others, nineteenth-century Russian periodicals, which were to some extent religious in nature. I paid little attention to "representative" periodicals of the Russian intelligentsia, such as "Otechestvennye Zapiski", "Sovremennik," or "Russkiy Vestnik". Instead, I focused on lesser-known religious, medical, and anthropological publications, the titles of which are given in the bibliography. The testimony of these sources led me to conclude that the phenomenon of holy madness consisted largely in the imposition of Christian legitimacy on shamanic behavior and that it was the fullest and most important manifestation of Russian double-faith. It owes its uniqueness not only to Slavic paganism, but also to some peculiarities of Ural-Altaic shamanism, which in the 19th century was widespread in Russia, and is now practiced by the Ural-Altaic tribes of Siberia.

A God's Fool, by Pavel Svedomsky (Source: Wikipedia)

On the basis of my research, I also came to the conclusion that the phenomenon of holy madness had a significant impact on the way Russians interpret their own culture. The question of the transfer of legitimacy from the holy madmen to Russian social and political life is discussed in the final, and perhaps the most controversial, chapter of this book. The hypothesis that different layers of culture share the same structural features has already been put forward by a variety of scholars, from anthropologists and historians to literary critics; however, there is seldom subsequent evidence to prove that this is the case. There are many difficulties in trying to demonstrate this. There is no generally accepted methodology for such endeavors, and there is little work that can serve as an example. At the time when I started this research, there were no such studies at all. Therefore, I am fully aware that by suggesting the existence of such a relationship, I am entering an area to which access is limited. However, I hope that my attempt to link together the various threads of Russian cultural and social life may be an impulse for further research on an object that has so far been seriously neglected, and the consequences of which go far beyond the mere phenomenon of holy madness.