Penal camps have a centuries-old "tradition". Many of them were established in isolated and unhealthy places of the world, where it was not possible to encourage free emigrants to settle. These were places where labor was needed to build roads and fortifications, to work on plantations, fell trees and extract natural resources.

One such place was the Kolyma region in the north-eastern part of Russia, where millions of prisoners lost their lives mining gold from under the ice. It is one of the coldest regions in the world, lying mostly beyond the Arctic Circle.

Kolyma on the map (Source: Wikipedia)

From the first days of their power, the Bolsheviks attached great importance to creating gold reserves. In the first years after the revolution, in order to cover the expenses for the suppression of the opposition, propaganda, espionage and diversion, they sold valuables confiscated from the rich houses of the bourgeoisie, in monasteries, and churches. Crown jewels and church utensils were sold to jewelers abroad.

Already in 1928-1929 it was discovered that Kolyma had huge gold reserves and it was immediately put under the exclusive administration of the NKVD. In 1931, Dalstroi (Дальстро́й, Far North Construction Association) was established to take care of prisoners forced to work in the mining industry in the area.

It is a land of darkness, snowstorms, howling winds and despair. During the long, polar winter, which lasts there for most of the year, the temperature usually drops to 60° C below zero. The vegetation is dominated by taiga and tundra. It is a land of permafrost. During the polar day, the ground thaws there only 20-30 cm (8-12 in) deep and mud forms, which is difficult to walk through.

Stalin established over 100 slave labor camps in Kolyma. These camps were intended for the "enemies of the people", in which the Soviet authorities included all Poles who resisted the invasion of the Red Army in 1939, opposed communism or otherwise defended the independence of their homeland.

Prisoner in Kolyma (Source: www.kolyma.ru)

Prisoners were transported under escort by trains to Vladivostok, and from there they were transported in inhumane conditions below ship decks to the port of Magadan, where they were sorted and transported to the camps.

In 1939-1940, about 10,000 Poles were deported to the Kolyma labor camps. They were separated from those previously imprisoned by moving them to mines located in the western part of the Dalstroi area, where working conditions were particularly harsh and dangerous.

Along the road stretching 1000 km (621 miles) from the port to the Lena River, camps were located at various distances. Prisoners dressed in rags forced to labor in the mines paid for it with their lives. A particularly high mortality rate of 75% occurred in winter.

Gold mining in Kolyma was carried out in two ways: the mining method, which was harder, as the gold was mined underground, and the open pit method, i.e. by digging into rock from the surface of the Earth.

The excavated rubble was transported on wheelbarrows and stored in huge heaps. When the polar day came, the aggregate was ground into smaller pieces, and then the golden sand was washed out of it in troughs lined with cloth. If the temperature during the polar night was lower than -62° C, no work was done on the surface.

There were norms at work and the allocation of food depended on their performance. It was often impossible to meet the work quota because the standards were very high and the starved and weak prisoners could not cope with them. The extremely difficult living conditions of the gulagers had an additional negative impact on their health.

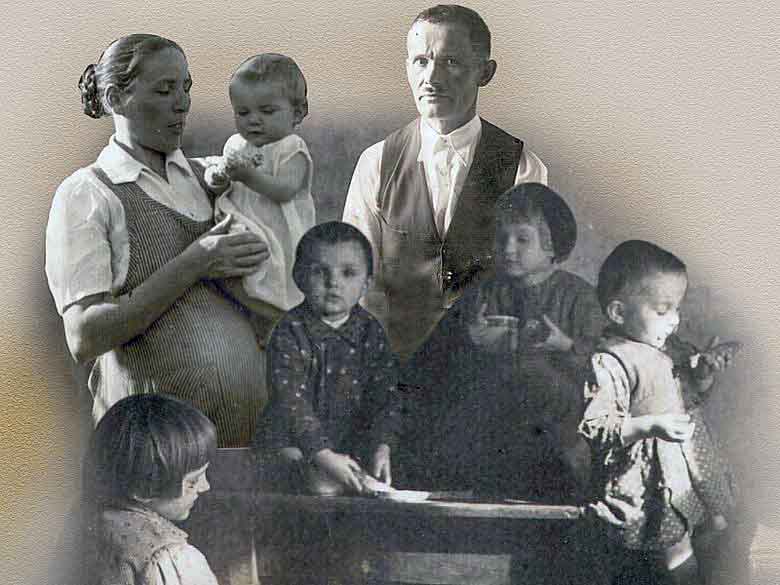

Children of the Kolyma camps (Source: www.kolyma.ru)

Mortality in Kolyma assumed enormous proportions. According to the best estimates, 75-80% of prisoners died within the first year of their stay.

Based on the testimonies of those rescued from Kolyma, it is calculated that each ton of gold mined equaled the lives of 1,000 prisoners who were tortured to death.

They were dying of hunger, cold and disease. They suffered from kidney disease, leg swelling, scurvy, blindness, severe frostbite resulting in amputation of limbs, bloody diarrhea and exhaustion. The daily "candy" cooked from mountain pine needles did not protect against scurvy. The few who managed to survive resembled skeletons.

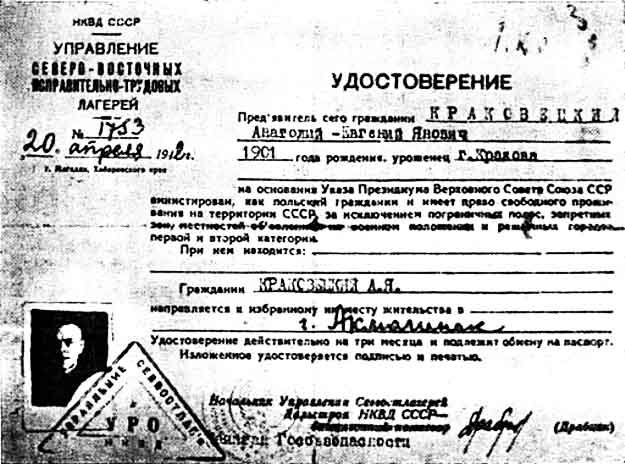

On the basis of an agreement between General Sikorski and Stalin, an amnesty was announced, under which Poles imprisoned in Russian labor camps should have been released. The news of this reached Kolyma late. The NKVD did not want to release most of the imprisoned Poles because of "unforgivable" political judgments, and in fact because of the fear of losing the workforce to fulfill the slave norms and production plans. The last released prisoners reported about a thousand Poles still detained and left in Kolyma. At the same time, the NKVD authorities gave misleading information about the location of the formation of the Polish Army.

Out of over 20,000 Poles sent to the mines in Kolyma, only 170 made it to the Anders Army, many without fingers or toes.

Soviet NKVD ticket for a freed Polish prisoner of the Kolyma camp, 1942 (Source: Wikipedia)

Bronisław Brzezicki, a prisoner of the Nakhodka Bay camp outside Vladivostok, recorded in his diary a shocking sight in the last days of his stay in the camp:

On September 20, 1941, after the so-called amnesty, a ship with a transport of about 1,000 Poles, prisoners returning from Kolyma, arrived at the nearby marina. When, after some time, the compact mass reached us and as if paraded in front of our ditches, leading each other by the hand, an amazing and blood-curdling sight presented itself to my eyes. Men in tatters, swaying shadows with stubbled faces, more spectral than human. It was a dramatic sight, incomparably more terrible than Grottger's painting depicting the deportation of Poles to Siberia. They were literally crippled, many without one eye, others completely blind, without noses, ears, without arms, on stilts, without legs...

Among the thousands of forced labor camps in the Soviet Union, Kolyma was a place of real extermination. Imprisoning innocent people on fabricated charges and forcing them to slave, exhausting work was sanctioned solely by the desire for power, industrialization and collectivization of the Soviet Union. This was done at the expense of thousands of Poles kidnapped from their homes — indentured slaves of the communist system.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.