The concept of historical awareness is more often used by historians than sociologists. The latter use them quite rarely, usually referring to the category of memory of the past or historical culture. This is due to the fact that for historians the issue of historical awareness most often means correct knowledge of history: events from the past, people, places. Sociologists, on the other hand, look at this issue in a broader dimension, as the entirety of the presence of history in the present — the common ideas about it, ways of commemoration and related rituals and practices.

Insurgents of 1944 (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

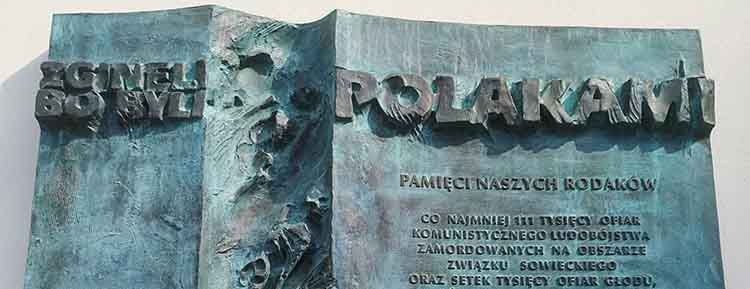

This means that memory is more imbued with emotions and values about what happened in the past, in which "correct" knowledge approved by historians is usually only an insignificant element, and sometimes even does not exist at all. If, after reading Henryk Sienkiewicz's novel, a specific idea about the past of our homeland appears in us, it is also an element of our ideas about history and sometimes even dominates our consciousness. This shows the paradoxes of memory, which is expressed in both family heirlooms and museums, street names, monuments and commemorative plaques. Therefore, memory and history surround us always and everywhere. In every product of culture there is an element of history. Whether we perceive it or not depends only on our sensitivity.

Speaking about the historical memory of Poles, we analyze it in the context of the nation's collective memory (national memory). It refers to the figures and events that collectively shape our image of the past and bind us to the national community. But each person participates in many memories, e.g. regional or family. They interpenetrate to varying degrees, sometimes excluding each other, sometimes stimulating each other.

What is the memory of Poles? The answers to this question can be found in the report "Education for Remembrance", which was commissioned by the Institute of National Remembrance. The research we have carried out is multidimensional and covers many segments and issues.

They indicate, for example, that the collective memory of the young generation of Poles resembles the memory of the older generation. If we ask young people what events from history or characters are important to them, they will usually mention the same ones that older respondents indicated. This fact indicates a relatively effective intergenerational transmission of memory. Of course, the frequency of these indications in different generations is not the same and these nuances, analyzed in detail, indicate the directions of further changes, sometimes disturbing.

Insurgents from the "Czata 49" Battalion after leaving the sewer near the exit of ul. Warecka on ul. New world. A characteristic patch with the letter "C" and the number 49 on the soldier's cap. September 2, 1944 (Source: Warsaw Uprising Museum)

For example, when formulating a ranking of events from Polish history that Poles feel proud of, the activity of NSZZ "Solidarity" appears only in the indications of the older generation — most young respondents do not mention it. Why is it so important? I always tell students that every nation had an important and great battle, every nation had a poet or explorer in its canon of heroes, but no nation has done what Solidarity did — none forced the authorities to register an independent trade union in the realities of a totalitarian state. And all this because of the phenomenon of grassroots social activity, based on moral values, and not on the basis of fighting with weapons in hand. Only Poles succeeded in this, and — in addition — on an unimaginable scale, because we are talking about a multi-million movement. I think, that "Solidarity" is unique on a global scale. Something similar is hard to find in the history of other nations and Poles are not aware of it.

I believe that the reason for this lies in the fact that we treat "Solidarity" as another independence uprising among many others, which makes it lose its uniqueness. We do not create the memory of it as an amazing phenomenon of social activity. Therefore, in a specific competition on the "market" of memory, "Solidarity", understood as it is today, will never "win" with, for example, the Warsaw Uprising and other heroic uprisings for independence. “Solidarity” is a different and absolutely unique phenomenon that requires a special approach, a completely different narrative.

Young people will leave school at some point and their contact with history will be limited to drawing on popular culture, film, or the Internet. Therefore, the question arises what image of history young Poles will go into the world with. If elements such as "Solidarity" do not appear in this picture, I dare say that historical education in this sense does not fulfill its role.

Of course, I am far from looking at the formation of memory as a technocrat who wants to form it by issuing orders and directives from above. I am a supporter of creating memory by saturating history teaching as much as possible with a reflective component, reflection on the relationship between what happened and our individual fate. Our report indicates that, unfortunately, such reverie does not appear among us very often. For most of us, history is a material to be "cuffed" in school, passed and forgotten. We do not undertake a deeper reflection on the "current relevance" of history, we do not treat it as a resource of useful knowledge for today. This is a serious problem that implies the fundamental question of why we need historical education at all.

Shooting position of the soldiers of the "Rafałki" platoon. The soldiers have the letter "R" and the emblem of Poland painted on their helmets. August 1944 (Source: Warsaw Uprising Museum)

Improving the education system in terms of shaping the functional memory of the past is an important challenge facing the Polish state. The report "Education for Remembrance" proves that 90 percent of schoolchildren are ready to devote their time — also extracurricular — to explore history through one of the activities, such as going to the field, visiting a memorial site, recording a conversation with a participant in historical events, preparing a project or reading an extra book. This is an issue worth attention because it shows that young people do not turn away from the word "history" — on the contrary, they are ready to explore it in a way that is attractive to them.

Cover of the report "Education for Remembrance" (Source: IPN)

It is also worth noting that most of the young people indicated during the survey that a visit to a death camp is, from their perspective, the most interesting form of contact with history. This type of contact was also indicated as the most reliable. This fact proves that young people expect not only attractions, but above all authenticity. In a place like KL Auschwitz there is no room for the proverbial fireworks. The space of the former German camps, places of torture and suffering screams without words. For the young generation staring at smartphone screens, it is still important and I think it is very optimistic piece of information. I hope that the results of the study "Education for Remembrance" will contribute to initiating a discussion on the problem of historical education. The material from the study suggests possible scenarios, indicates those that may meet with a good response, and those that will fail. The collected material — which is something absolutely unique in this type of research — allows one to compare the answers of students, the older generation and history teachers.

Reflecting on why remembering the past, let us be aware that memory is a key element shaping our identity. We often hear in the public space that there is too much history, that it is not so important nowadays, and that reflection on the past should be replaced with something more "useful". I believe that this is not true and our research confirms that there is a deep awareness among Poles of how important history is to us.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.