July 11, 2023 marks the 80th anniversary of the culmination of the Ukrainian genocide against Poles living in the Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic. The truth about these events has recently, but with difficulty, penetrated into the public consciousness.

During the People's Republic of Poland, it was carefully hidden, there was no place for it either in high school curricula or even within university curricula.

At present, for reasons of political correctness, the discussion of these painful events with our neighbor, Ukraine, is difficult and postponed for who knows when. For such conversations, any time is good, especially today. Any time is good for discovering the truth, understanding the mechanisms of those crimes, describing them and clearing up relations between the two neighboring nations — Polish and Ukrainian — especially today.

The concept of the Borderlands

Borderlands (Kresy) is the edge of the territory between our lands and other political entities. In the first Polish Republic, these were military watchtowers defending the eastern and southern borders against the attacks of the Tatars and Turks. The borders of the First Polish Republic in the sixteenth century reached from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea and covered territories where people of different nationalities and different cultures lived.

As a result of various external conditions and internal squabbles, the territory of the Polish state began to shrink until it was completely taken over by the neighboring countries — Russia, Prussia and Austria. For 123 years there was no Polish state and there was no concept of "Borderlands". After regaining independence in 1918, it appears again, but it has a different meaning, because the Second Polish Republic is very different from the first. It is a country several times smaller in terms of territory and national relations within it are organized differently.

Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (Source: Wikipedia)

Borderlands, within the meaning of the Second Republic of Poland, constitute 52% of the territory of the Polish state and cover eight out of sixteen voivodeships. These are eastern voivodeships where the Polish population was a minority. Borderlands played a very important role in the development of culture and the formation of our national identity.

Among the five most important cities of the Second Polish Republic (Kraków, Warsaw, Poznań, Vilnius and Lviv), two are located within the Borderlands. Two famous universities operated in these cities —Stefan Batory in Vilnius and Jan Kazimierz in Lviv. Two of the most eminent poets, Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, began their activities in the Eastern Borderlands, in Vilnius. The Borderlands were described by the writers Henryk Sienkiewicz and Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, and a famous school of mathematicians with Stefan Banach and Stanisław Ulam was founded in Lviv. Paul Baran, the creator of the foundations of modern network communication, also comes from the Polish Borderlands (Grodno).

The Borderlands created a huge cultural potential for the entire Republic of Poland, but also for the civilization of the world. We are the heirs of these values. So how did it happen that as a result of the barbaric actions of the Ukrainian nationalists, everything was so deeply re-evaluated?

Causes of Polish-Ukrainian conflicts

In the Second Polish Republic, there were 35 million Polish citizens, including 12 million citizens of other cultures and customs, including 5 million Ruthenians who turned into Ukrainians, 3.5 million Jews, 2 million Belarusians, one million Germans, 200,000 Russians, tens of thousands of Czechs, Gypsies, Armenians and other nations. These twelve million people, hailing from cultural circles other than Polish, were able to arrange their social relations. They lived next to each other, became friends, celebrated their Catholic and Orthodox holidays together, started mixed families. And so it remained in the northern provinces.

The situation is different in the southern voivodships — Volyn, Lwów, Stanisławów and Tarnopol. Here, the Ruthenians, later called Ukrainians, constitute the vast demographic majority, but they do not constitute the majority in the administration, they do not determine economic development and culture. The Polish and Jewish minorities definitely dominate in these areas.

The beginnings of the conflict could be seen in 1918, when the monarchies fall and the fight for a new division of land takes place. Poles want to rebuild their state within the borders of the First Polish Republic, and a strong national feeling is awakening among the Ukrainians and they want to build their own state on these lands. In 1918, the Polish-Ukrainian war takes place, from which we are left with images of the Eaglets of Lwów fighting for Lviv, or the figure of General Józef Haller and the Blue Army fighting for the eastern borders of Poland.

The Ukrainians lose this war, but they continue to fight the Poles by way of terror, manifested in attacks on Polish offices — post offices, railways — on Polish officials (e.g. the attack on the Minister of Internal Affairs Bronisław Pieracki). This is a foretaste of what will happen during the Second World War, and it will intensify especially in 1943-44.

The birth of the Bandera ideology

In the interwar period, in the Borderlands, especially in the southern provinces, various concepts of creating a Ukrainian state were being hatched. All these concepts were accompanied by nationalism. The creators of the foundations of the ideology, which later took the name of Banderism, are the author of "Nationalism" (1926) Dmytro Dontsov, and the author of "Decalogue of the Ukrainian Nationalist" (1929) Stepan Lenkawski.

Both positions were of great importance in the formation of the Ukrainian nationalist doctrine. These were guidelines modeled on the fascist-Nazi ideology, on the Nazi manifesto "Mein Kampf", showing the path that must be followed in order to build a Ukrainian state. The dominant element in this process of "building" was hatred towards other nations inhabiting the "disputed" territories, which, according to Ukrainian ideologues, should belong exclusively to Ukrainians.

The outbreak of World War II was a favorable circumstance for the implementation of these nationalist ideas. After September 17, 1939, Poland ceases to exist again. The Ukrainians were just waiting for such a moment. They were prepared to create the structures of their state. They had administrative foundations in the form of the structures of the UON (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists), a highly radicalized ideology, and political and military leaders — Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevich, Andriy Melnyk, Petro Olijnyk, Dmytro Klachkivsky, Vasyl Ivakhov and Ivan Lytvynchuk, who decided that these lands must be cleansed of national minorities. Klaczkiwski was the commander of the UPA-North (Ukraińska Powstańcza Armia, Ukrainian Insurgent Army) and personally ordered the murder of Poles in Volhynia.

The Genocide called Volyn Massacre

The crime of genocide is defined as an act "committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such." In Polish science, the Volhynian Crime is referred to as genocidal ethnic cleansing, the Volhynian (or Volhynian-Galician) Crime or Massacre.

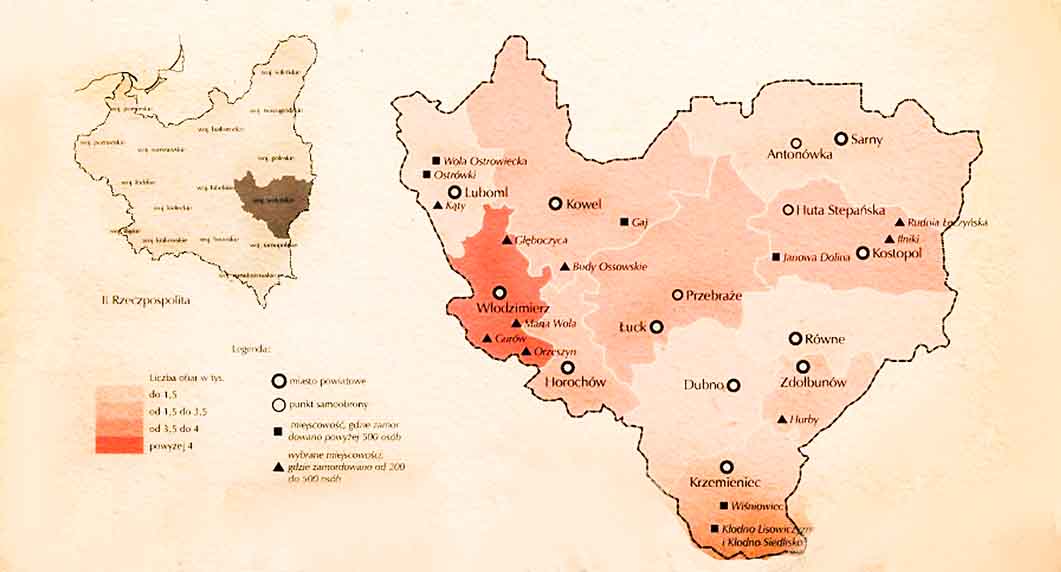

Map of crimes committed by Ukrainian nationalists against Poles in the Volyn province in 1943 (from the exhibition of the Gdańsk branch of the Institute of National Remembrance "Wołyń 1943"; author: Agnieszka Gumińska, graphic design: Bartłomiej Siwek, retouch: Andrzej Woźniewicz. Source: IPN)

Since after the September 1939 defeat Poland was deprived of any possibility of armed defense (it had no army, police or border guards), Ukrainian nationalists started ethnic cleansing in the Borderlands, the victims of which were national minorities, but above all Poles. What we conventionally call the Volhynian Massacre, the apogee of which falls on July 11, 1943, began after September 17, 1939. The first murders took place in the Tarnopol province as early as 1939 in the counties of Buczacz, Brzeżany and Podhajce. A wave of murders then swept about fifty villages, attacked and slaughtered en masse. Crime moved to the northern areas and in 1943 it reached Volhynia.

In the early summer of 1943, the leadership of the OUN-UPA (Organizacja Ukraińskich Nacjonalistów–Ukraińska Powstańcza Armia, Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists–Ukrainian Insurgent Army) approved a secret plan to physically annihilate all Poles in Volhynia. This plan was meticulously implemented. More and more villages were attacked, everyone was murdered, possessions were stolen, and buildings were burned so that there was no possibility of return.

The total number of victims of the Massacre has not been established to this day. We can only rely on rough estimates. In Volhynia alone, there were at least 60,000. killed. In the remaining voivodships, where Ukrainians continued ethnic cleansing in the following months, almost 50,000-80,000 more people could have died. The figures are frightening considering the speed of extermination. Even more shocking are the accounts of how executions were carried out on the Polish population.

The Ukrainians were characterized by extraordinary, even by the standards of World War II, cruelty. Witness accounts, preserved evidence, but also conclusions from the exhumation of the victims, clearly indicate that the Ukrainian militias, emboldened by the extermination of the Jewish population by the Germans, were deprived of any legal or moral restraints. They used sophisticated methods of torture that defied all standards of warfare and departed from any definition of humanism and Christian ethics.

The crime scene in Lipniki, bodies of murdered Poles (1943) (Source: Wikipedia)

They were incited to murder on religious and social grounds. No one was spared. The murdered Poles had their limbs cut off, their eyes gouged out, their insides ripped out, the children impaled on spikes in the fences. The researchers of the Institute of National Remembrance counted 368 sophisticated, especially cruel methods of murder. A particularly popular form of killing people was setting fire to buildings (including churches) in which the inhabitants of a given village were gathered. Many of the attacks took place on Sundays when the population was gathering for church services. The bulletin of the Institute of National Remembrance from 2009 reads, among others:

In the summer and autumn of 1943, the terror of the OUN-UPA reached enormous proportions. The murders of the Polish population, which began in the counties of Sarnenski, Kostopolski, Równe and Zdołbunowski, in June 1943 spread to the counties of Dubno and Łuck, and in July covered the area of Kowel, Włodzimierz and Horochowski, and in August also the poviat of Lubomelski. July 1943 was particularly bloody, especially Sunday, July 11, 1943. July 11, 1943 was called "Bloody Sunday" for a reason. On that day, 99 towns were pacified. People praying in churches were attacked, set on fire and murdered in a sophisticated way. Many of the attacked towns were razed to the ground, the population was completely wiped out. The attacks involved Ukrainian peasants equipped with everyday tools that could be used in combat - saws, scythes, axes, hammers, pitchforks, rakes. After the pacification, the property was plundered and the victims were buried in mass pits. Hastily organized Polish self-defence units were unable to effectively counteract the overwhelming enemy, especially when it attacked by surprise. The extermination of Huta Pieniacka in 1944 can serve as an example of genocide. Within six hours, a large Polish village ceased to exist. The inhabitants were gathered in barns by several dozen and set on fire.

It should be emphasized that not everyone agreed with the ideology of Banderism and therefore became its victims. Among the Ukrainians there were also many "righteous" people who saved Poles. Czechs, Armenians, Gypsies and Ukrainians who did not want to cooperate with the OUN-UPA also fell victim to the purges.

The killings stopped in mid-1944. At that time, Home Army units began to operate more actively, but the Polish population had already been effectively wiped out. The war then ended, but the murders and reprisals continued almost until 1948.

In the times of People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union, the Volhynia crime was not discussed at all — it was forbidden to talk about it out loud. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic gained an independent statehood, but the social system and young democracy were born with great difficulty. They were looking for hero examples while creating their identity.

Particularly outrageous is the fact that the independent Ukrainian state has not yet been able to condemn the anti-Polish activities of the OUN and UPA, and their leaders, people such as Bandera, Shukhevych or Klaczkiwski, are considered national heroes and monuments are being erected in their honor. Decisions on the exhumation of mass graves and the dignified burial of victims of genocide are made dependent on the reconstruction of UPA monuments in Poland. Gestures of this type are rightly perceived in Poland as manifestations of hostility and attempts to open wounds that are still unhealed.

What's next?

The Volhynia massacre was a huge tragedy and catastrophe, not only for the Polish population, for people living in the Borderlands, but also for the Polish state. During the extermination, hundreds of thousands of Poles were physically annihilated (it is estimated that the number of victims could reach even 200,000), and many centuries of Polish culture built in the Borderland region were destroyed along with them. The interrupted history and the drama that took place are a civilizational and cultural disaster.

Crime cannot be separated from culture and science. History is a continuity, an interpenetration of centuries of matter. The ties that had connected Poles and Ukrainians who had lived in these areas for several hundred years were destroyed.

Remembrance of the past, including painful events, is the responsibility of both countries - now free, independent, willing to implement the plan of rebuilding friendly relations in the spirit of solidarity and forgiveness. The horrors of war should not be an absolution for the bestial murders of innocent people. Poles and Ukrainians, despite their tragic past, remain neighbors and neither country can change its geographical location. We are doomed to live side by side. The point is to arrange mutual relations as best as possible.

Unwanted in many Polish cities, the Volhynian Massacre monument by master Andrzej Pityński will be erected in Dostawa, in the commune of Jarocin . (Source: Social Committee for the Construction of the Monument)

After eighty years, there is an urgent need for a thorough explanation of the past, based not on emotions but on historical truth, followed by clarification. An introduction to the reconciliation should be the exhumation of the bodies of the murdered and honoring them with a dignified Christian burial. "For it is not for revenge, but for rememberance that the victims cry out."

It seems desirable to prepare a broad educational campaign in the form of documentaries, exhibitions, lectures, competitions, etc. addressed to the young generation of Poles, but also Ukrainians living in Poland and Ukraine.

It seems that the 80th anniversary of the genocide in the Borderlands, in the face of the current events of the war in Ukraine, is a good moment to allow Ukrainians to understand the position of Poles and to bring about reconciliation. Even if it is not based on love, let it be the result of rational economic and diplomatic considerations — calculations that are beneficial to both nations.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.