The dominant aspect, if we look at the more than three hundred years of existence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, when it was inhabited and co-created by about ten generations of citizens, remains the tradition of freedom and citizenship, which was shaped by two hundred and several dozen Sejms, by thousands of assemblies. The deep roots of this tradition meant that people drawing from the spiritual achievements of the Polish-Lithuanian state, brought up by the stories of their ancestors, could not agree to life with a bent neck.

Insurgents (author unknown) (Source: gov.pl/PAP)

In the past, the nations of today's Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus used to elect their own rulers and had personal and property freedom, which was a guarantee of security from state violence. Nihil novi sine communi consensu – “nothing new without the general consent” – was the principle on which the political life of the Republic of Poland was founded. It is the basis of the spirit of freedom, which did not agree to the imposition of an alien lifestyle from the outside. It is from this principle that the desire for independence and readiness to fight for the most precious cause, for dignity and freedom, grows.

Parallel to the memory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, there is the heritage of the tradition of uprisings against oppressors in the 18th century. Its sources can be found in the confederation called Dzików (1733), which was the first uprising against enslavement, against the powers that took away Poland's independence within its borders at the time. This became clear in 1733, when the Russian army entered the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in order to impose on it a ruler favored by the Tsarina of Russia and the Austrian emperor, and to prevent the rule by the one chosen by Polish citizens. The reaction to this situation was an uprising. The Bar Confederation (1768–1772) was another armed act against the authority imposed from outside, which was a reaction to the humiliation that the Russian ambassador inflicted on the senators of the Republic of Poland, kidnapping them from the center of Warsaw and transporting them deep into Russia. Then the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) breaks out, followed by the Greater Poland Uprising (1806), which brought about the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, and the most famous one — the November Uprising of 1830/1831. It is followed by even less known uprisings: the Krakow Uprising (1846), a series of uprisings from the Spring of Nations (1848).

It can be calculated that in 130 years (from 1733 to 1863) five to ten uprisings broke out — depending on which we take into account. This means that in a very large proportion of the families of noble origin and in many a bourgeois families, and sometimes even in peasant families, there was a memory that one had to fight for one's dignity, even if the fight was seemingly impossible to win; that persisting in a submissive, humble attitude distorts human nature and one should try to straighten one's bent neck.

Setting the beginning of the insurrection for January 1863 was associated with the impressment (pol. branka) ordered by the authorities — a forced conscription to the Russian army. Branka was in response to the constant development of the underground movement, numbering about 20,000 sworn-in young people. Between the November Uprising and the January Uprising, in the years 1832-55, the Russian authorities selected 200,000 recruits from the Kingdom of Poland, a tiny entity with 4-5 million inhabitants, of which 175,000 were lost forever in the Russian Empire. The small land on the Vistula River lost 175 thousand. people only because they had to fight under duress for the Russian empire. The reaction of the insurgents was an expression of protest against the local youth dying on the Caucasus range, or in Kazakhstan, for the glory of the Russian emperor.

Image "The conscription of Poles to the Russian army in 1863", Aleksander Sochaczewski (Source: Wikipedia/Maciej Szczepańczyk/lic. CC)

The outbreak of the January Uprising led to a diplomatic crisis on the European political scene. The rapprochement of Prussia and Russia, which was a response to the initiation of the uprising, met with the reaction of France, Great Britain, and Austria. In May 1863, there was a chance for a war between Russia and the Western powers. When we say that the January Uprising had no chance of success, we forget about this fact. In actuality, no other uprising was so close to causing a European war, in which the Polish side had a chance to obtain external assistance from Western countries.

Farewell to Europe, a painting by Aleksander Sochaczewski. The theme of the painting is the exile of Poles to Siberia after defeating them in the January Uprising (1863) against the Russian Empire. The painting shows the stop of the exiled convoy at the obelisk marking the border between Europe and Asia. The artist himself is among those exiled here, next to the obelisk, on the right. (Source: Wikipedia)

It is little known that it was then that Russia lost Alaska due to the January Uprising. The threat of war with Great Britain and France multiplied the costs of servicing the Russian debt, and this, combined with the high costs of pacifying the January Uprising, led to a situation in which the Russian treasury de facto became bankrupt. The finance minister begged the tsar to sell Alaska in order to obtain funds — ultimately a paltry $7 million — to keep the specter of bankruptcy away from Russia. It was an indirect result of the January Uprising, which needs to be remembered.

An issue worth noting is the supranational nature of the January Uprising. The symbol of this insurrection, which was the last joint uprising of the nations of the First Polish Republic, was a triple emblem, containing not only the Eagle, but also the Vytis (the White Knight) and St. Michael the Archangel — a symbol of Kiev, Ukraine, where this uprising, although less pronounced, was also marked. The rebellion of 1863 in Lithuania was powerful and involved almost exclusively peasants who had revolted against the same invader with whom the Polish nobility had fought, i.e. Russia. The latter deprived them not only of political freedom, but also of religious freedom. Earlier, e.g. in the Kościuszko Uprising or the November Uprising, the nobility of Lithuanian origin, often speaking Polish, walked arm-in-arm with the Crown nobles, i.e. ethnic Poles, fighting for freedom against a common enemy. This confirms that the Commonwealth did not cease to be a unity until 1863. In 2023, we can say that, spiritually, it has not ceased to be, as evidenced by Ukraine.

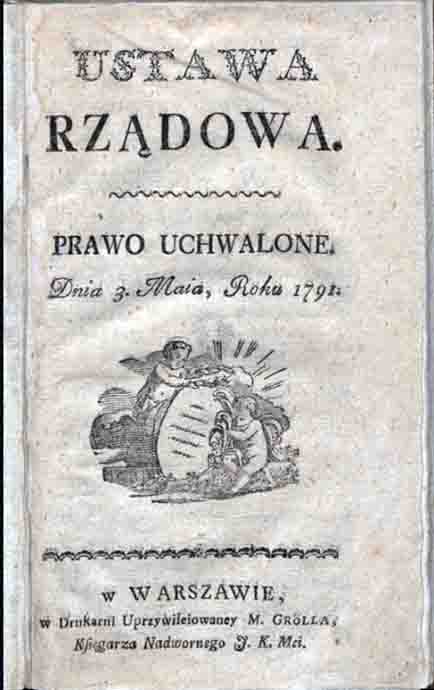

If we take into account the psychological factor — the spiritual legacy of the Republic of Poland and the tradition of fighting for freedom that lived in the consciousness of the January insurgents — as well as the political climate accompanying the decision to initiate the insurrection, the popular claim that the Polish romantic spirit is the antithesis of reason must collapse. This belief has its roots in the Enlightenment propaganda, which was directed against the Commonwealth. It intensified especially when the Polish-Lithuanian state began to recover from the collapse, when the legislation of the Great Sejm was prepared and the Constitution of May 3 was finally adopted.

From the moment Stanisław August Poniatowski announced his program of reforms in 1764, propaganda has been intensifying, financed on the one hand by Empress Catherine II of Russia, and on the other by Frederick II, who jointly hired the greatest heads and pens of the French and German Enlightenment, led by Voltaire. The avalanche of texts defaming Poland created by these enlightened hosts perpetuated harmful stereotypes. One of them was the belief that Poles are madmen and romantics who tilt at windmills. On top of all this, one must add Prussian propaganda aimed at the Kościuszko Uprising, presenting it as a romantic gesture ending in tragedy for the Republic of Poland. It was then that the image of Kościuszko falling down, allegedly uttering the words Finis Poloniae!, or "The end of Poland!", was disseminated.

Thaddeus Kosciuszko at Racławice, painting by Wojciech Kossak (Source: Wikipedia)

We should not forget that uprisings are not only a Polish specialty. We can find them as a very important part of the Irish tradition, they are also an important part of the identity of Italy, Germany, Spain, Hungary, but also Russia, which has in its history both victorious and lost uprisings. However, what determines the uniqueness of Poland, and at the same time gives rise to suspicions of excessive romanticism, is the fact that Polish uprisings had to face not one opponent, as was the case with Ireland or Hungary, but three at once.

Three continental powers — Russia, Prussia and Austria — dismantled the Commonwealth in the years 1772–1795. The importance of the Polish question lies in the fact that it affected the three greatest powers simultaneously, which made it a matter of great importance, and gave our struggles for independence a particularly difficult character. This fact makes taking up a fight with a rational goal seem like madness. The difficulty of the victory was due to the strength of the opponents who tried to prevent Poland from winning. Today, however, we live in a free country, which is the best proof that the uprisings were not a failure.

Without persistent reminding of the fact that Poland exists, is alive and has not resigned to the verdict of the powers, we would not have regained independence in 1918. Constantly advocating for freedom is part of our identity. After World War I, of course, the geopolitical map changed. In 1918, Poland was not founded alone, but a whole series of other, smaller, weaker states were established, which, it would seem, would be doomed to non-existence in the face of the interests of empires. The existence of Ukraine, Lithuania, Slovakia, or even the Czech Republic is to some extent determined by the persistent demands of Poles for the nation's right to independence. And this is our precious heritage. On the other hand, those who adore empires and believe that only they should rule the world, because they are the guarantor of order, have the right to condemn the Polish uprisings.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.