The history of Polish Texans is not very well known. Very few people among the Polish diaspora realize that Texas was the first landing place for Polish refugees escaping the hardships after the November Uprising of 1830; also the site of the first Polish settlement in America; the first home for a Polish Catholic church and parishes on the continent; and the location of the first Polish-language school. Lots of "firsts" here!

Likewise, few people realize that Texas (260,000 sq. miles) is more than twice the size of Poland (121,000 sq. miles). By comparison, it's closer from Warsaw to Paris then it is from North to South Texas, or from East to West Texas! On the other hand, Texas — while being somewhat less populous (29 million inhabitants in Texas, versus 38 million in Poland) — has a GDP of $1.8 trillion and is the 10th largest economy in the world.

Polish Texans were, for many years, one of the most isolated, tradition-preserving, conservative, and rural ethnic groups in the state. According to the 2000 US census, there are at least 228,309 Texans of Polish ancestry.

Professor Mazurkiewicz

"Polish Texans: The History of Texas Polonia" was the title of a presentation by professor Jim Mazurkiewicz delivered at St. Thomas University in Houston, on October 4, 2021. Dr. Mazurkiewicz is a prominent leader of Texas Polonia, Professor and Regents Fellow Texas A&M University (TAMU), as well as doctor honoris causa SGGW, Warsaw. He is the Leadership Program Director for Texas A&M AgriLife Extension and Texas A&M University Professor in the Department of Agriculture Leadership, Education & Communications, and that's just scratching the surface of his numerous posts and accomplishments. He is a native of the Brazos Valley. His family originally settled in Washington County at the end of the ninetieth century and they still own and operate the family farm in Chappell Hill, Texas.

Dr. Mazurkiewicz is a true Texan. To wit, in his spare time, he operates a commercial beef cattle herd, and he is a certified national as well as international beef cattle judge. Yet, he always proudly proclaims that he is "a fifth generation Pole," and he has no qualms speaking in a Polish dialect reminiscent of Wielkopolska (the Greater Poland) from where his family arrived in Texas, with an admittedly heavy accent, but unimitable eloquence, passion, and directness.

In his lecture, Dr. Mazurkiewicz gave a grand tour of the history of Polish Texans, starting with the earliest settlers who arrived in 1818 at Champ d'Asile, near Liberty, Texas, according to historical records. These were several Polish soldiers who had served in Napoleon's defeated armies, who ended up in Texas fighting for its freedom. Champ d'Asile unfortunately broke up eight months after its establishment as hunger, sickness, and other misfortunes did their work.

The Town of Goliad

In 1821, Captain Joseph Alexander Czyczeryn joined Dr. James Long's second, unsuccessful filibustering expedition into Spanish Texas. A filibuster is someone who engages in a formally unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country or territory to foment or support a political revolution or secession. These attempts happened with some regularity, but just as the first James Long expedition, and many others under different leaders, this one ended up in capitulation and imprisonment of the filibusters after a three-day siege of La Bahia (now Goliad) by Mexican forces.

Later, several Polish soldiers, including Michael Debricki, the brothers Francis and Adolph Petrussewicz, and John Kortickey, were in the ill-fated army of Colonel Fannin. This group, composed of about four hundred men, mostly American volunteers, was surrounded by a force five times greater under Gen. Urrea, near the same town of Goliad which was the scene of Dr. Long's adventure. On March 11, 1836, over two hundred remaining officers and soldiers were overpowered and captured. On Palm Sunday, March 27th, the Mexicans marched the prisoners out by detachments under the pretext of setting them free and shot down nearly all of them. Of the Poles, only J. Kortickey is thought to have escaped (according to [4], contrary to the account of Dr. Mazurkiewicz).

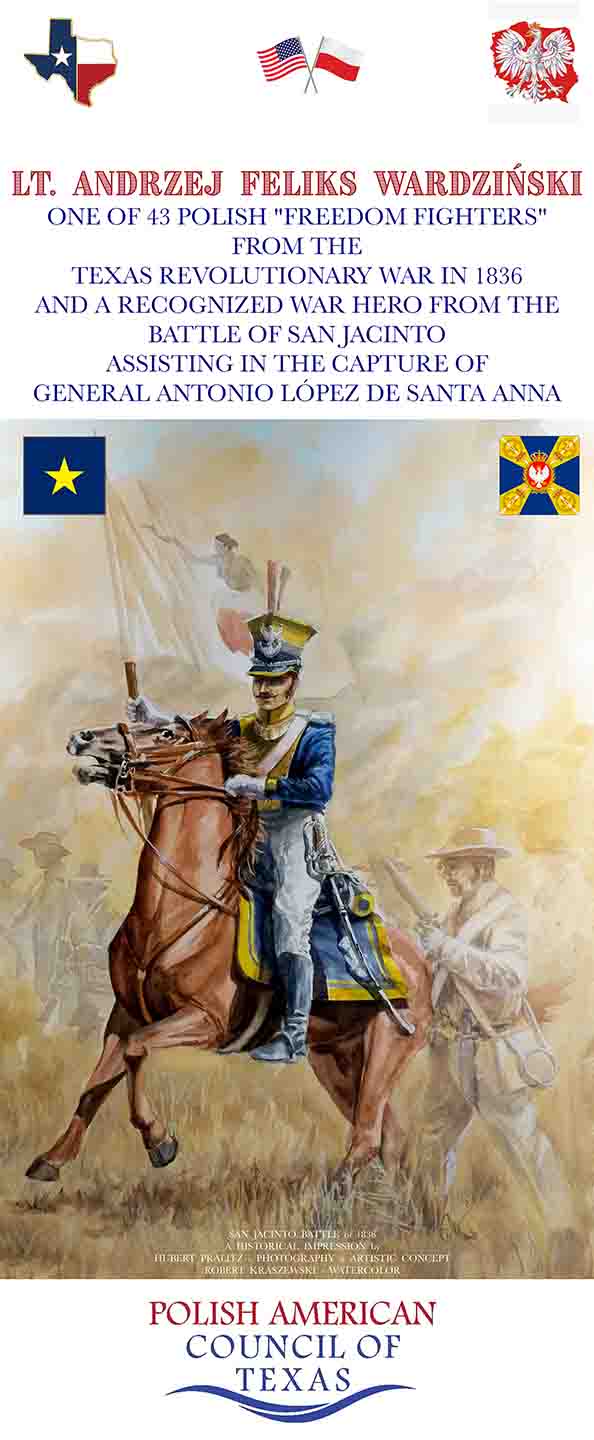

Lt. Andrzej Feliks Wardziński

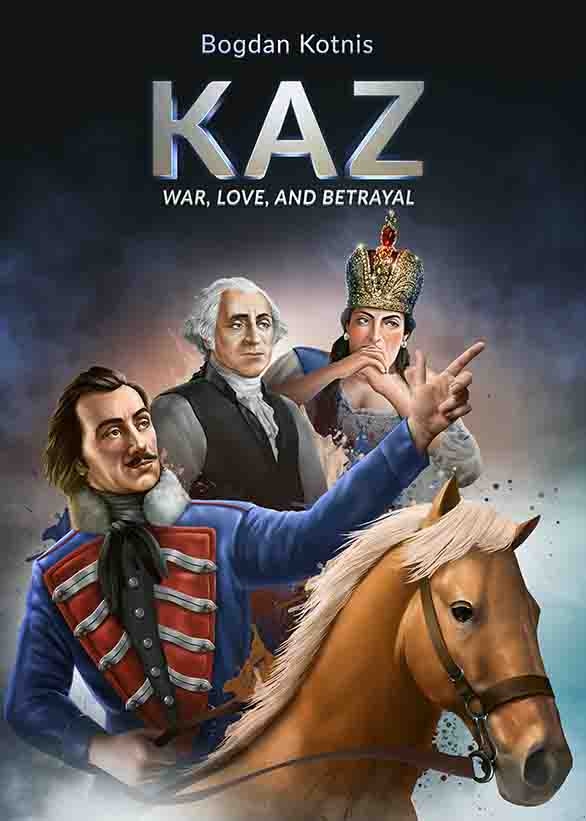

After their unsuccessful uprising against Russia in 1830-1831, known as the November Uprising, many Poles left for abroad. Some of these found the Texas Revolution timely and sufficiently exciting — and excitingly dangerous. Among them was Lt. Andrzej Feliks Wardziński, an officer trained at the Military Academy in Warsaw. He and other Polish refugees, a total of 235, arrived in New York City on July 14, 1834. Most of them were officers in the November Uprising. Wardziński was quickly recruited by Lt. Amasa Turner, and although he was an experienced officer and leader, he was given the rank of private due to his lack of English language skills, but that did not deter him from becoming one of the top heroes of Texas. In total there were 43 Polish "Freedom Fighters" that fought for Texas independence in 1836, of which Lt. Wardziński was the most prominent.

A poster by Hubert Pralitz (photography, historic and artistic design), Robert Kraszewski (watercolor), courtesy of Polish American Council of Texas

The Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna personally directed the action against the insurrection and employed ruthless means to suppress the independence movement. He soon met with a defeat, however, at the hands of Gen. Sam Houston at San Jacinto and it was Wardziński's patrol that delivered gen. Santa Anna on April 22, 1836 to Sam Houston. For his service, Lt. Wardziński received land from Texas in Harris County. Even though he could have retired to his farm then, in 1845 he joined the US army in a fight against Mexico and served until Feb. 2, 1848.

In 1936, during the Texas Centennial Exposition, it was announced that he will have his name inscribed along with Sam Houston and Stephen F Austin in the Texas Hall of State in Dallas — becoming one of the three biggest heroes of Texas.

Additionally, Michael Dembiński, Frederick Lemsky, plus six additional Poles fought under general Sam Houston at San Jacinto, and all of them survived.

Father Leopold Moczygemba

The man who opened Texas to Polish mass immigration — and started a new chapter in the history of Polish immigration in the United States — was Father Leopold Moczygemba, a Franciscan monk.

On September 1, 1852, Moczygemba arrived at Galveston and served as pastor to German immigrants in New Braunfels and Castroville, Texas, until December 1854. Born in 1824 in Płużnica Wielka, Upper Silesia, he received much of his education in Italy and was admitted into the Franciscan Order in 1849. Later, while studying in Germany, he volunteered for missionary service among the German Texans. He served in New Braunfels, Castroville, and Fredericksburg and quickly recognizing the opportunities in Texas, he wrote glowing letters to his relatives and friends that effectively started an emigration fever around his birthplace.

The first group of this movement, numbered about one hundred families from the Upper Silesia, chartered a sailing vessel and landed at Galveston in 1854, bringing with them not only their household goods and agricultural implements, but also a large crucifix and bells from their church in Poland. When they arrived in Texas, yellow fever epidemic was raging on shore and the 6-month-long inland trek to the settlement on the San Antonio River was miserable. They eventually settled in Karnes County and founded the village of Panna Maria (Virgin Mary). The first mass was said beneath a large oak tree on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1854. However, the discomfort of famine, exposure, and disease caused resentment among the colonists, with Father Moczygemba bearing its brunt and being forced to resign and leave after 18 months.

Two years later, he became the first Commissary General of the Conventual Franciscans in the United States. He worked in Kentucky, New York, Illinois, and Michigan. In Detroit, in 1885, with Father Joseph Dobrowski, another Polish priest in Texas, he established the oldest Polish American Institution of higher learning: Saint Mary's College of Saints Cyril and Methodius Seminary.

Father Moczygemba died on February 23, 1891 and was buried in Detroit, Michigan. On October 13, 1974 his remains were reinterred at Panna Maria, Texas, near the same oak tree where he said the first mass for the Polish immigrants on December 24, 1854.

"Za chlebem" (For the Bread)

Not everyone emigrating from Poland to Texas was a soldier. For example, in 1853, Erasmus Andrew Florian (Florian Liskowacki) born is Zasław, in Subkarpatian Voivodship, Poland, in 1813, came to Texas and prospered as a successful banker there, and established the first insurance agency in Texas, in San Antonio.

On April 23, 1867, the second wave of about 100 Polish immigrants arrived from Wielkopolska and Kujawy (Prussian partition) to New Waverly, Plantersville, and Industry, Texas (Brazos Valley) led by Meyer Levy, a Polish Jew from Kcynia, Poland.

Throughout early 1880s, Polonia, Texas, continued to be settled by Polish immigrants from Wielkopolska (Greater Poland) and Kujawy. Polish immigrants arriving from all three partitions continued to come to Texas until the beginning of WWI. These were predominantly economically driven immigrants, looking for a way to make ends meet. Many of them decided on America, where there supposedly was land, jobs, freedom, and opportunity, as the solution to their problems.

Most of the Poles who settled in the United States did not find that land, however. They ended up working in the mines, mills, factories, and packinghouses of such cities as Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Buffalo, but the Poles who came to Texas were exceptions in that regard. In many cases, they arrived as essentially indentured servants, lured in as the result of the labor shortage after the Civil War, labored at cotton plantations replacing the newly emancipated slaves. They eventually found land thanks to being able to accumulate enough capital due to their hard labor and thrift. [5]

Just as important to the immigrants as the land was the preservation of the Old World language and faith. Like many other Catholic immigrant groups, the Poles believed that language and faith were intimately related, that any loss of the language among the community would inevitably lead to a loss of religion, perhaps even conversion to the Protestant values of the surrounding East Texas culture. [5] By the late 1830s, Texas had more Polish Catholic parishes South of San Antonio and along the Brazos River than any other state in the US.

The parochial schools helped preserve the language and culture of the Old World. The first of them was St. Joseph. It was established in New Waverly, in 1866, making it the first Polish school in America.

Journal of the 1800s

Here are the highlights of Dr. Mazurkiewicz's lecture, covering the eighteenth century:

1841: Alphonse Pisarenski, Texas Santa Fe expedition.

1841: Bernard and Benjamin Kowalski came from Inowrocław (Kujawy) and established businesses in Brownsville. Ben's 6 sons: mayor, 2 oil executives, insurance, lawyer, engineer.

1835: Alexander Werbiski born in Warsaw in 1817, participated in 1830 uprising, escaped to the US and after the Mexican War established a mercantile business in Brownsville and served in the Texas Legislature in 1872 and was the first mayor of Brownsville.

1854: Kiolbassa family from Swibie, Silesia and Stanislaus was a member of the Prussian Assembly in Berlin before coming to Texas. His brothers Frank and Bernard were successful businessmen in San Antonio.

1855: Charles Radziminski was a refugee of the 1830 uprising and came to the US in 1834, later came to Texas in 1855 as a soldier, engineer, and surveyor.

1855: Kalkst Wolski came to Texas and was a member of 1830 uprising. He is noted as the first Polish travel writer in Texas. Born in 1816 in Potoczek near Lublin and educated in Warsaw. His book Do Ameryki i w Ameryce (To America and In America) appeared in 1876.

1856: Joseph Cotulla registered his brand in Panna Maria Post Office in 1865. He was born in Wielkie Strzelce (Wielkopolska). Established Cotulla, Texas in 1881-82.

1866: Bishop of Galveston brought Resurrectionists priests, Polish missionaries to Texas. The order ws founded in Paris in 1843.

1866 Vicar General Adolf Bakanowski became the first Vicar General of Polish Missions in Texas. His memoirs about the Texas frontier were published in Polish in Lwów, in 1913.

1869: Joe & Ed Kotulla met in San Antonio at the Menger Hotel and flipped a coin to see who would keep the original spelling of their name. Ed won. Both men originally settled in Panna Maria.

1876: St Stefan Wagner born in Belencin (Wielkopolska) came to Texas in 1853 as a teacher. Interested in medicine, he attended St. Louis Medical School and returned to Texas to practice in Bellville, New Waverly, Bremond, and finally in Houston. He ws a real estate broker and key leader of Houston Polonia.

1862: William Dobrowolski was born in St. Hedwig, Texas. Adopted by Ed Kotulla, William became a very successful businessman in San Antonio. Active in St. Michael Church & St. Albert's Polish Society in San Antonio.

1867: Leonard W Oryński was born in Łęczyca (Pomerania) in 1845. He fled after the uprising of 1863 and joined forces with Maximilian in 1864. When Maximillian was killed in 1867, he fled to San Antonio and became a prominent pharmacist in the 1880s.

The Big Picture

According to Professor Mazurkiewicz, there were four major waves of Polish immigration to Texas:

- "Za chlebem" (for the bread), mostly from Silesia (Prussian partition) since 1854.

- Also "za chlebem", Wielkopolska and Kujawy (Prussian partition) and Małopolska (Galicia, Austro-Hungarian partition) since 1867.

- "Solidarnościowa" (Solidarity), after WWI in 1918, after WW2 in 1945, and after martial law in 1981, from all over Poland, seeking freedom.

- "Dla gospodarki" (for the economy), since 2000 to present, from all over Poland, California, U.S. Midwest, and East Coast.

We may add that, preceding the first wave "za chlebem," was the influx of many seasoned and talented soldiers after the November and January uprisings of 1830 and 1863 respectively. Perhaps we could suggest it as the "wave zero" of the Polish immigration to Texas...

The first two "major craddles" of Polish immigration to Texas were Panna Maria and New Waverly, with Panna Maria being justly proud of the fact that it is the oldest purely Polish settlement in the United States.

In conclusion of Dr. Mazurkiewicz's lecture, the Polish people that have come to Texas have helped shape the culture of Texas through their Catholic faith, music, food, traditions, and work ethic highlighting the values of faith, family, friendship, an freedom.

The Message

It's only appropriate to conclude with the call-to-action and directive for the Texas Polonia that Dr. Mazurkiewicz presented in one of his slides:

If Polonia in Texas is to survive, we must work together as one Polonia, including old and new Polonia in all activities, events, and projects.

There is no future Polonia without the new immigrants. The influx of new Polish immigrants helps keep our culture and heritage alive and strong.

We must involve and invest in our youth or there will be no Polonia in the future with no one to lead.

In addition, there is no future in Polonia without recognizing all of Texas Polonia, including all rural and urban Polish communities.

Dr. Jim Mazurkiewicz

President, PACT

This message by Dr. mazurkiewicz can and should definitely be extended beyond Texas, to the entire Polish community in the United States. Our strength lies in unity.