Today is the 85th anniversary of the Soviet aggression against Poland. On September 17, 1939, in the early morning hours, the Soviet Union attacked Poland by force of arms. In this way, Stalin fulfilled the August secret agreement with Hitler (the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact), which provided for joint aggression against the Republic of Poland, the occupation and division of its territory, and the effective liquidation of the Polish state.

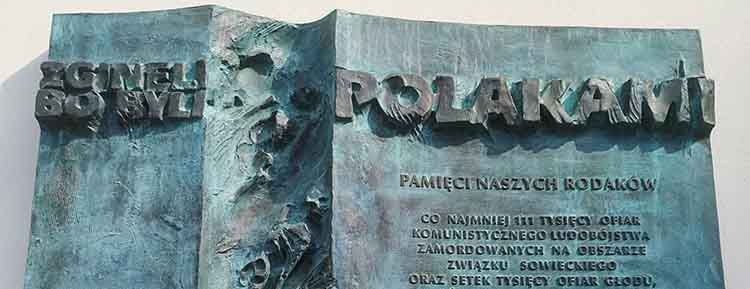

If we wanted to erect a monument in the form of a simple wall, with the names, surnames and places of origin of people who died in the Eastern Borderlands as a result of World War II and the Soviet occupation, or were deported and never returned to Poland, we would build the largest monument in the world. However, we cannot erect even such a simple monument, because after almost 100 years since those events, we do not know all the names and surnames of the victims of those events.

A huge part of those murdered and repressed by the Soviet regime were members of the intelligentsia. Estimating the scale of losses suffered by the Polish intelligentsia in the Eastern Borderlands during World War II is a very difficult undertaking. This is primarily due to the fact that we do not have full lists of the names of those lost. The term "loss" itself is not a homogeneous category either. In addition to those murdered, whose counting is somewhat easier, we have a whole host of those who were deported deep into the Soviet Union, where they died in various circumstances, or — if they were more fortunate — survived until the soldiers of General Władysław Anders took them to the West. Some of them never returned to Poland, which is a permanent end result and indicates the heterogeneity of the concept of "losses" in the context of the intelligentsia.

With this in mind, it is easier to understand the scale of the challenges facing researchers who are trying to estimate the losses suffered by the Polish intelligentsia in the Eastern Borderlands during World War II. This is not only historical work, but also archaeological one. Documents from the era were deliberately destroyed. What remains is largely due to chance; it is only a part of the entire source material and there is no chance today of recovering the rest — it simply no longer exists. We are able to reconstruct certain things by comparing the state before the outbreak of the war to the reality later, but this will not allow us to effectively estimate the total losses.

The intelligentsia was the social group that the Soviets feared the most. It served as a kind of heart of the nation. Without it, society was more susceptible to denationalization and ideologization — the basic actions of the new government. A nation of farmers and workers — although these were extremely important and necessary professions — without the intelligentsia would not survive. The Soviets therefore counted on the liquidation of the nation "on the spot" by destroying the most important centers of Polish intelligentsia in the east. In connection with this, Soviet actions were aimed, for example, at the Lviv community centered around the Jan Kazimierz (John Casimir) University and other institutions, which together constituted the most important Polish scientific center in the interwar period. Only Warsaw could match it.

The inauguration of the academic year at the University of Lwów. (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

Lviv was famous for its brilliant school of mathematics, which we remember to this day. Fewer people realize that there was also an excellent humanities community there. Excellent and pioneering medical research was also conducted in Lviv, e.g. on typhus. This fantastic intelligentsia center was not only destroyed, but also expunged from our consciousness for many decades. The Soviet plan to completely erase the Lviv center from the memory of Poles fortunately failed, but the losses incurred as a result of the USSR's policy were multidimensional and multiplied by years of perpetuation.

It is worth taking a closer look at the specifics of the provinces in the eastern borderlands of the Second Polish Republic. The level of civilization there was not high. Schools often served as the only centers of local intelligentsia culture, and the universities in Lviv and Vilnius were the two beacons of special importance. The Soviets were aware of this, which is why they struck at these centers first. They closed down the universities, removed all the professors, took away their apartments and banished them from the cities, condemning them to pauperization. At a later stage, they struck at teachers of grammar schools and lower-level schools. They robbed the assets of educational institutions, devastated their property, and destroyed library resources. The scale of the destruction was enormous.

In the context of Soviet crimes committed on Polish soil during World War II, the aspect of contemporary society's awareness of these actions is also important. There is no doubt that a crime is always a crime, and a kind of bidding war over which regime – the Soviet or the Nazi – caused more damage to Poland is pointless. Both the Germans and the Russians acted in a brutal and unjustifiable manner. However, knowledge about German crimes is more widely disseminated among Poles, which is mainly due to the fact that during the Polish People's Republic, it was possible to talk about them freely and conduct scientific research on them, while in the case of Soviet crimes, it was the other way around – censorship effectively blocked any manifestations of taking up this topic in the public space. There was of course a second circulation, where this topic was present, but official information channels were blocked for these issues. Over time, society got used to this state of affairs.

From the perspective of Polish historians, the situation is similar. For decades, they did not have access to documents and other sources on the Soviets' dealings with the intelligentsia in the Eastern Borderlands. There was a District (State) Archive in Lviv that collected these materials, but subsequent generations of researchers not only did not have access to it, but – especially in the case of the younger generation – did not even know what could be found there. As a result, the memory of Soviet crimes is only now gradually being recreated. Historians are trying to restore their status as equal to German crimes in the public consciousness; to make people realize how much they influenced the Polish nation and its culture. This is an important, long-term and very necessary task.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.