"Miracle on the Vistula" is a term commonly used to refer to the fighting near Warsaw, which took place in August 1920 during the Polish-Russian war. In these fights, the Polish army resisted the Bolshevik forces, which sought to continue their westward expansion in order to spread the communist revolution. The reviving Poland stood in the way of the Bolsheviks and successfully opposed their expansion. In the history of Poland, there are only a few battles so important for the fate of our country and, simultaneously, for the entire world at the time.

The claws of the Bolshevik bear were reaching much further then. The German state, immersed in the chaos of war defeat, was constantly teetering on the brink of mass revolution. Soviet forces, if they found themselves on the borders of Germany, could change the course of history there. According to Lenin and his comrades, the revolution was to spread much wider. The Bolshevik army, having supported the revolution in the Western countries, could advance to all of Europe, and their hypocritical ideology could spread even to the whole world.

Jakub Różalski, Hammer and Sickle, digital illustration (Source: Pinterest)

The so-called Battle of Warsaw, although – contrary to the name – it took place not only in the vicinity of Warsaw, but in an area of several hundred kilometers from Grudziądz and Toruń in the north, to Dęblin and Puławy in the south [12], was one of the key events of the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1920 and was of great importance for the future of Central and Eastern Europe.

Polish troops, led by Marshal Józef Piłsudski, finally repelled the Bolshevik offensive, which stopped the advance of the Red Army on Polish territory. This victory played a key role in stopping the Bolshevik expansion to the west and had an impact on shaping the future political arrangement in the region.

Year 1918

The official date of the outbreak of the Polish-Soviet war is disputed among historians. There is no specific date, and no one has ever declared war on anyone.

The first clashes between Polish soldiers and the Bolsheviks took place in February and March 1918, long before November 11, before the armistice was signed after World War I. [1]

For Western Europe, it was the year of the end of the wartime struggles. For Poland, the war simply wasn't over in 1918, as the Bolsheviks continued to push westward and the borders with Germany remained fluid.

Year 1919

In 1919, when our country entered the first year of its independence, not a single border was formally established. Especially in the eastern borderlands, the situation was confusing, and Poland and Russia were not the only players there. The Ukrainians had their national ambitions and created as many as two states: eastern and western. Lithuanians and Latvians also sought independence. At that time, the German army was still in these areas. And Russia was divided into red, revolutionary, and white, continuing the tsarist tradition, and was in the midst of a civil war. There were lots of players.

On February 7, Piłsudski said:

At the moment, Poland is virtually borderless and everything we can get in the West depends on the Entente and how much it wants to squeeze Germany. In the East, it's a different matter; here, there is a door that opens and closes, and it all depends on who opens it and how far by force... [3]

Poland, despite the Entente's pressure to support the opponents of the Bolshevik revolution, under the leadership of Piłsudski remained neutral, which is understandable, because both the red revolutionaries and the whites treated the territories of the Russian partition as their own lands, neither promising anything, nor recognizing Poland.

The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, took advantage of the existing situation, following the retreating German troops, and occupied further areas of Lithuania and Belarus. In January 1919, they reached Vilnius and did not intend to stop. The unambiguous and ominous codename of the Bolshevik operation was "Target — Vistula". The seed of communist power, the Revolutionary Military Council of Poland, was ready. In February, the authorities of the socialist Soviet republics of Lithuania and Belarus were installed.

Józef Piłsudski in Poznań, 1919 (Source: Wikipedia)

Before Piłsudski could move against the Soviets, he had to reach an agreement with the Germans regarding the evacuation of their troops. It was not until February 5, 1919, that the Germans agreed to let 10,000 Poles east to form a front against the Bolsheviks.

The Polish army reached the Nemunas river and initially everything seemed to be a success, because a significant part of the Bolshevik army was then redirected to the battle with the Whites, but in February they took Kiev. In March 1919, the Polish army reached Lida. Piłsudski decided to attack Vilnius.

On April 16, 1919, Polish troops launched an offensive. The Bolsheviks were surprised by the attack of the Polish cavalry of Colonel Władysław Belina-Prażmowski, supported by infantry under the command of General Rydz-Śmigły, and after a few days, on April 21 (Wet Monday — the second day of Easter), using the considerable support of the city's inhabitants, Vilnius is in Polish hands, and the Chief of State Józef Piłsudski is triumphantly greeted at the railway station.

The next day, on Tuesday, April 22, Piłsudski issued a proclamation "To the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania", in which he wrote, among others:

Your country has not known freedom for a hundred and fifty years, oppressed by hostile Russian, German and Bolshevik violence – violence which, without asking the population, imposed foreign patterns of behavior, limiting the will, often breaking life.

I want to give you the opportunity to resolve internal, national, and religious matters as you wish, without any violence or oppression from Poland. [2]

This declaration of self-determination for all nationalities of the pre-partition Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth met with enthusiasm of the Polish-speaking part of the area's inhabitants, but the Belarusian side remained completely passive, and the Lithuanians were deeply disturbed by this idea. Their then government, residing in Kaunas, strongly protested. [3]

In turn, when Vilnius was still being stormed, Piłsudski was already anxiously looking at the western borders. The Germans wanted to regain Greater Poland and Pomerania. They had up to a million soldiers at their disposal. An alliance even began to emerge between the Germans and the Russians, the first talks on the coordination of the attack took place. The Germans called Poland a "seasonal state" and rejected aid to Poland ahead of the Bolshevik invasion. Fortunately, the French tried to curb German appetites. [4]

In the winter, at the end of 1919, the hostilities in the east seemed to come to a standstill. Some thought the war was over.

Year 1920

The Soviets initially pushed for peace. In their peace proposals one could read that Russia "recognizes Poland's independence" and "is devoid of any aggressive intentions" — these empty words of Soviet propaganda turned out to be more than effective, especially on the public opinion of the West. At the same time, however, the Soviets made every effort to strengthen their western front, preparing for war with Poland, as Lenin clearly described for internal use. [4]

Poles lost the propaganda war all over Europe at that time. According to the Western public opinion, it was the Poles who were the aggressors. The West could not see through the real intentions of the Leninist revolutionaries, for whom communism was an idea to recreate a new Russian empire, only with a different economic system. It always seemed to the West that communism and Marxism were the incarnation of lofty humanist ideals. Many people in Europe and America regarded them with sympathy and support. The true nature of the Bolshevik revolution remained unfathomable, because information about it reached only sporadically and was manipulated by the Soviet propaganda.

From the very beginning of its existence, Bolshevik Russia wanted to subjugate all the western lands of the former Russian Empire, including eastern Poland. Gradually, it expanded its influence and sought to seize new lands, regardless of the views of their inhabitants.

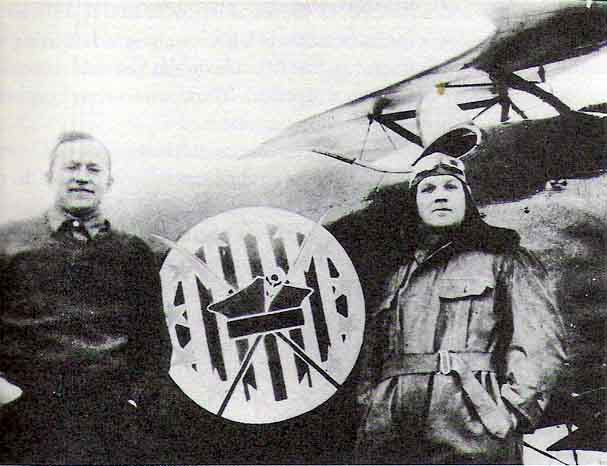

Józef Piłsudski and Edward Rydz-Śmigły, 1920 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ultimately, the resumption of the war in the spring of 1920 was decided by Piłsudski's vote. [4] He decided that there was no point in waiting for the Bolsheviks to grow even stronger and that a decisive confrontation with them should be sought. Let us remember that for Poland the war — which was never formally declared — was simply still going on and it was already in its sixth year.

The Polish army, which at the end of 1918 did not number more than 5,000, grew to 600,000 at the beginning of 1920. A lot of volunteers appeared, and a conscription was ordered later.

The reconstruction of the army was an absolute priority for the new Polish authorities, although it was not without problems. Expenses for this purpose consumed more than half of the young country's budget. The officers came mainly from the partitioning armies, so integrating them into the ranks of one army was a problem. There were various problems, including language issues. There were no uniforms. Haste resulted in lack of training — some recruits began to learn to shoot... only in the front lines.

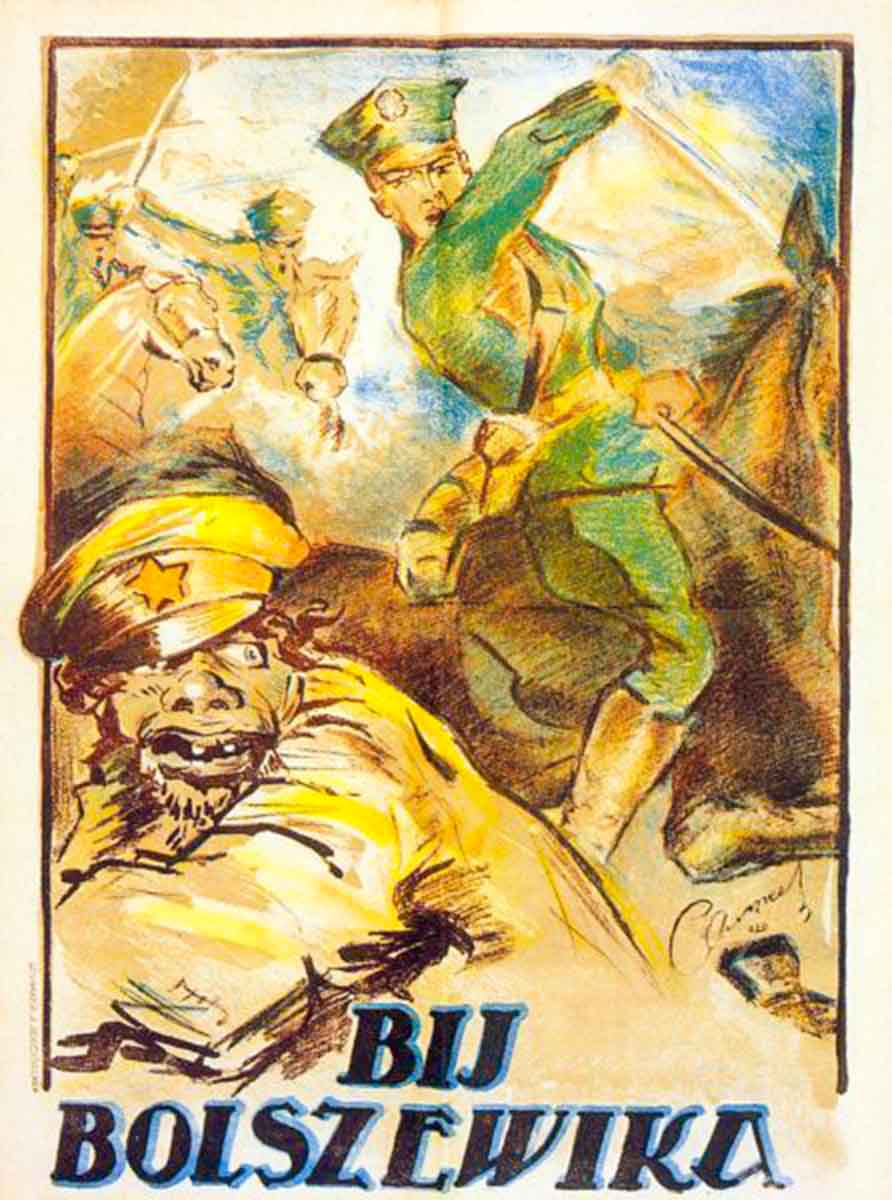

Beat the Bolshevik! , Polish propaganda poster from 1920. photo. Polish Army Museum in Warsaw (Source: Museum of the Polish Army)

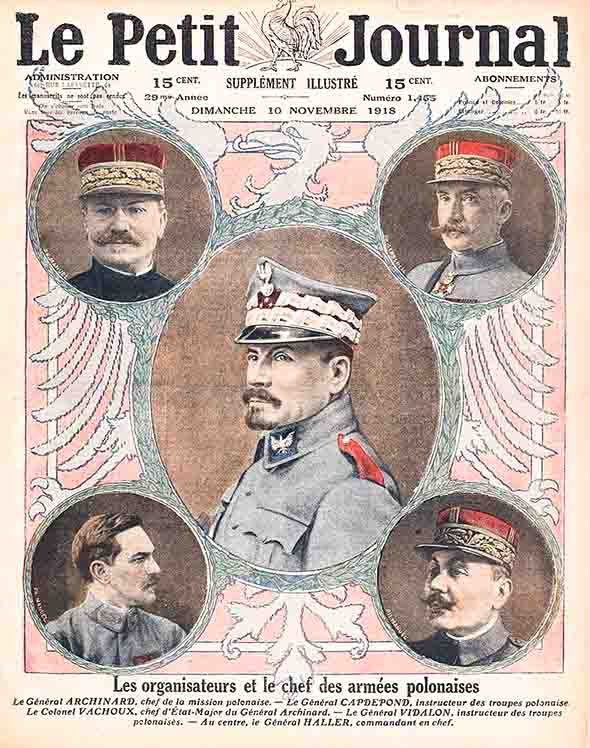

Such an army, although somewhat reinforced by the army of General Haller, well trained and equipped in France with the money of the American Polonia, faced the Red Army from 1918. For Piłsudski, it was only a matter of time before the Russians would attack again. In the spring of 1920, under his influence, a course of action was set, although — as it turned out later — it was, unfortunately, the wrong direction.

The Kiev Expedition

The battles for eastern Galicia had been going on for over a year and a half. Kiev and Lviv were the axis of the southern theater of war, one of the two war theaters in eastern Poland where future borders were decided, in addition to the northern theater, with the axis based on Vilnius and Minsk.

At the beginning of 1920, Lviv was in Polish hands; Kyiv - Soviet. Ukraine was in a critical situation after the collapse of the two previous republics. Backed to the wall, the head of the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, Symon Petliura, turned to Piłsudski for help.

Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petliura, 1920 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Piłsudski, partly as a result of incorrect information and a tempting vision from the Ukrainian side [4], entered into a political and military alliance with Petliura. In it, Poland recognized the sovereignty of the Ukrainian People's Republic (URL), renounced the territories of the pre-partition Republic east of the established border line with Ukraine, and committed itself to a joint fight against the Bolsheviks. The Ukrainian People's Republic relinquished its rights to the lands of Eastern Galicia previously occupied by the West Ukrainian People's Republic. [5]

The Head of the Polish State considered Kiev to be the key place where the final confrontation and resolution of the conflict with Russia would take place. All the time he hoped to create a system of buffer states, led by Poland, which would separate Poland from Russia. In return for renouncing Eastern Galicia and Lviv for Poland, he supported the government of Petliura. They went to war together.

60,000 Polish soldiers and only 4,000 Ukrainians took part in the offensive, which began on April 24, 1920. However, it ended up in a vacuum. Polish-Ukrainian troops, not encountering much resistance, occupied subsequent cities almost without fighting and, on May 3, they found themselves near Kiev.

Apparently, the attack on the city began with a rally… on a streetcar. [4] On May 5, a Polish patrol entered the city center on a captured streetcar, took a prisoner — a Russian officer — and returned safely. On May 7, Kyiv was under control. But the decisive confrontations, which the Marshal hoped for, did not take place. The Bolshevik bear has holed up somewhere deep in the forest. All of the Right Bank Ukraine was taken at the cost of only 150 dead and 300 wounded. [5]

On May 9, a joint Polish-Ukrainian parade was held in the center of Kiev. The High Command of the Polish Army, trying to prevent the local Ukrainian population from interpreting the temporary presence of Polish troops as an occupation, ordered that only Ukrainian flags be hung on the offices, and Polish flags only on buildings occupied by the Polish command.

The Polish army enters Kiev, Wielka Włodzimierska Street, May 7, 1920 (Source: Wikipedia)

On May 18, 1920, Józef Piłsudski returned from the Kiev expedition to Warsaw. In the capital, he was given a reception worthy of Roman emperors. At the station, he was greeted with the song "God, who shielded Poland...". The Marshal was welcomed by the government led by Prime Minister Leopold Skulski. The enthusiastic crowd uncoupled the Supreme Commander's carriage and hauled it up to the parliament building by hand. "Since the times of Kircholm and Khotyn, the Polish nation has not experienced such triumphs of its arms." said Marshal Wojciech Trąpczyński, otherwise a political opponent of Piłsudski, in the Sejm. [6] "The people have lost their sense of reality," ironically wrote the then little-known French military adviser Charles De Gaulle.

The main strategic objective of the campaign was to break up and destroy at least one of the Bolshevik armies stationed in Ukraine. Due to their withdrawal without making serious attempts to defend themselves, this goal was not achieved.

Despite the capture of Kiev, i.e. the achievement of the territorial goal, the response of the Ukrainians, in spite of the appeals of Piłsudski and Petliura, was very weak. Tired of several years of wars, requisitions and robberies, the society passively watched the "lording over" of successive foreign armies. Some Ukrainians feared the return of the "Polish masters", but the news of the "red terror" against peasants in left-bank Ukraine had not yet reached them. [5] Thus the political goal was not achieved, either.

On May 26, the Red Army launched a counter-offensive. Its core in the south was Semyon Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army brought from the Caucasus. Mikhail Tukhachevsky's offensive was launched in the north. The stake in the war was Polish independence, and perhaps also the fate of the whole of Europe. [6]

The Polish defense was forced to retreat, suffering heavy losses. On June 5, two Bolshevik cavalry divisions broke through the Polish front; plundering and murdering, over the next few days, they took over Żytomierz and Berdyczów. On June 8, the High Command of the Polish Army ordered the retreat of Polish troops from the Ukraine.

Thus ended the "Kiev expedition" in terms of military operations. As a result, not only all territorial gains were given back, but also Volhynia and part of Eastern Galicia. [5] In addition, it was the Poles who became the aggressors in the opinion of both the West and for the purposes of internal propaganda in Russia. The Russians consider Kiev to this day to be the cradle of their statehood and the Kiev expedition aroused holy indignation in them.

Poland's Political Failure

Poland's situation in the summer of 1920 was, to put it mildly, delicate. The Red Army was advancing from the east. In the north, the Germans won plebiscites in Warmia and Mazury and were just waiting to enter Pomerania or Wielkopolska. Transports of weapons to Poland did not arrive, blocked by the Germans and Czechs, but also by dock workers in England and Gdańsk. Poland had a very bad press. The Soviets declared her the aggressor everywhere. [4]

As a result, the Allies — in exchange for their dubious help in the face of Poland's expected defeat in the fight against the Bolsheviks — demanded the return of Vilnius to Lithuania, Cieszyn Silesia to Czechoslovakia, recognition of the Curzon line — i.e. the demarcation line arbitrarily drawn by the English based on the river Bug — and the newly elected Polish Prime Minister Władysław Grabski agreed to these humiliating for Poland conditions at the conference in Spa, Belgium, where he went against Piłsudski's will.

Władysław Grabski (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Only now, for a change, the Soviets did not agree to the peace terms, seeing in this agreement a conspiracy that was to deprive them of the final victory. Lenin summed up the attempts at mediation with the words: "By means of petty trickery they want to take away our victory." [20] The Bolshevik command counted on a quick capture of Poland and the entry of Soviet troops into Germany, where a general revolution was to break out. Their winter peace offerings have long since given way to the euphoria of victory and grand plans for further conquest.

The Allied proposals were outdated before the conference was over but, as a result of his negotiating ineptitude, Grabski had to resign a month after his inauguration. He was replaced by the Wincenty Witos Government of National Defense.

Wincenty Witos, 1920 (Source: Wikipedia)

Piłsudski's depression

War defeats quickly knocked Piłsudski off his pedestal. The chief himself was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He lost his composure, he was overcome by depression, helplessness. [4] He was lost, arguing with everyone, constantly bickering about the fall of the "morals" of the soldiers. Everyone failed him (except himself). [19] He decided that — in the battle for Warsaw — he would personally command the maneuvering group on the Wieprz river.

On August 12, in the face of an apparently imminent defeat, he even handed over to Witos his resignation from the function of the Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief, which the Prime Minister did not accept, although Piłsudski's resignation was not only expected, but even demanded by almost everyone, including the Western Allies . [11]

In this letter, he indicated, among other things, that not knowing if and when he would be able to return from the battlefield, whose fate he considered uncertain, he asked me and authorized me to replace him in his office. As for the thing itself and the letter, he asks for absolute secrecy for as long as relations require, and I myself consider it necessary. — Wincenty Witos, 1974

After his resignation, Piłsudski went to visit his mistress (later wife) and daughters, who were staying in Bobowa, in southern Poland, and was absent for at least two days. Does someone who is the commander-in-chief resign in the most difficult, disaster-marked moment? Maybe it was just too much for him and he couldn't handle it? [19]

The Bolshevik counter-offensive

The euphoria in connection with the capture of Kiev by the Poles lasted very briefly. In May 1920, the "Red Napoleon" as he was known, general Mikhail Tukhachevsky, reappeared on the scene and struck with a force of 70,000 troops, recapturing Kiev.

In June, in the south, the attack was launched by Budyonny's famous cavalry army brought in from the Caucasus, about whose efficiency, cruelty and ruthlessness there were legends. After the capture of Żytomierz, it brutally slaughtered the entire crew. In Berdyczów, it burned down a hospital with 600 wounded. The Polish army was retreating in this section of the front, but could not be defeated, although there was fatigue and lack of food and fodder. [4]

On the other hand, in the northern part of the front, the Russians had a significant numerical advantage: 120,000. soldiers, compared to less than 60,000 Polish troops. Already on the first day of the Bolshevik attack, two lines of Polish defense were broken. The Poles, divided into smaller groups, retreated in an uncoordinated manner. There was no strategic plan.

Poland was in a very difficult situation. Tukhachevsky's Red Army troops quickly crossed the Bug River and headed towards Warsaw. In the south, Lwów was also threatened by Budyonny. The Polish army was forced to constantly retreat. The Bolsheviks continued to press forward.

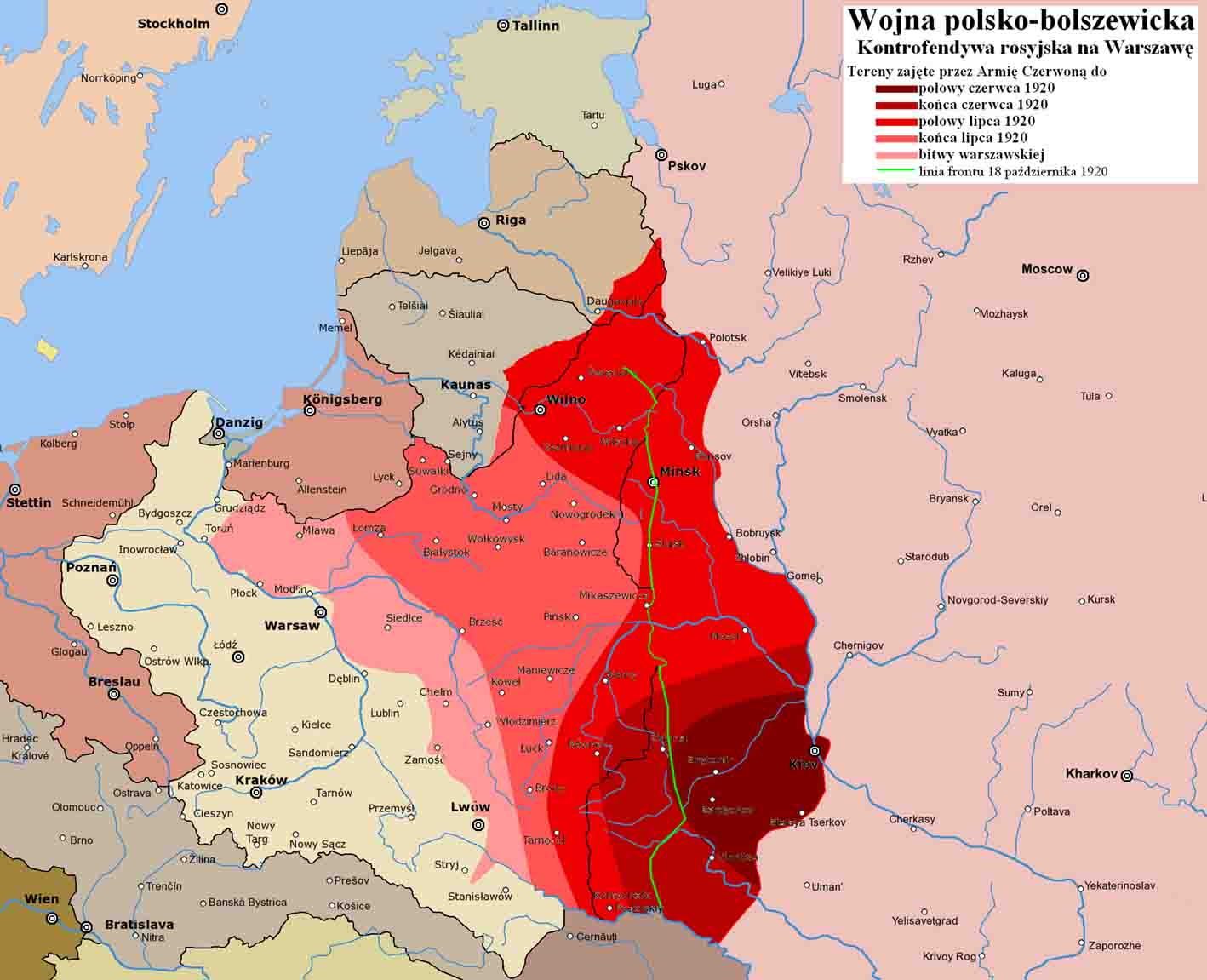

Bolshevik counteroffensive against Warsaw (Photo Mixx321). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0.. (Source: Histmag.org)

Tukhachevsky, commanding the Western Front from his headquarters in Minsk (Belarus), was confident of success. He believed that Warsaw could be captured immediately. [11]

Meanwhile, the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee, i.e. the future government of the Bolshevik Polish Republic of Soviets, was already waiting for the capture of Warsaw. Communists Julian Marchlewski and Feliks Dzierżyński, who had already been soiled with the blood of innocent people, as envoys of the Soviet puppet government established at the end of July in Smolensk, waited on August 15 near Warsaw for city's fall in order to introduce bloody rule there. In a manner tried and tested during the Bolshevik revolution, they followed the front line in an armored train, introducing revolutionary terror with arrests and shootings wherever they went. Looking back over the next quarter of a century, this puppet government was an ominous sign. [4][11]

Worse still, Poland was mostly left to fend for itself. Great Britain and France, our Western allies, provided only limited assistance in the form of military equipment and ammunition. At any rate, these deliveries were effectively blocked by workers succumbing to Soviet propaganda in countries such as England, Belgium, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and also in Gdańsk.

The suggestions from the allies at this point varied, though generally focused on playing for time. The English proposed a withdrawal as far as Poznań. The French - fortification on the line of the Vistula. None of them even thought about offensive actions. It was all about just stopping the front.

Although the Polish army looked broken and overcome by a wave of fatalism and depression [4], the situation was not really that hopeless. For the sake of completeness, the appearance of the Soviet troops at that time was also not the best. Many soldiers marched barefoot. Not all of them had rifles — they would only get them in the trenches, leftovers from the dead or the badly wounded.

The number of troops of both sides was similar, about 100,000. soldiers. However, the Polish army was acutely lacking not only in training and equipment, but especially in ammunition. So much so that soldiers who "unnecessarily" used up ammunition were punished. Without additional supplies, Polish ammunition stocks would run out on August 14 at the latest. [7]

A bilingual (Hungarian/Polish) plaque on the front of the town hall in Csepel (Budapest) commemorating Hungary's aid to Poland. "In paying tribute to the Hungarian nation that has provided friendly assistance to the Republic of Poland threatened with death by the Bolshevik aggression. In the time of our struggles decisive importance, August 12, 1920 a transport of 22 million rounds of ammunition arrived in Skierniewice from Budapest, by the Manfred Weiss Establishments at Csepel. Between 1919 and 1921 the Kingdom of Hungary sent to Poland some 100 million carbine cartridges as well as artillery shells and military equipment in large quantities. Grateful Polish Nation. March 2012" (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

And here one could look for one of these true "miracles". On August 12, 1920, a significant transport of ammunition from Hungary arrived in Skierniewice.

At the request of the Poles, the Hungarian Minister of Defense, Károly Soós, earlier made available to Poland the entire stock of ammunition of the Hungarian army at that time, and ordered the production of the native factory exclusively for the needs of the fighting Poland. This time, the 80 wagons that set off from Budapest on July 27 carried about 22 million rifle cartridges. This transport traveled through Romania, and on August 12 reached Skierniewice. This way, among other, the Kingdom of Hungary contributed to the Polish victory. [8]

The Battle of Warsaw

The face of this war was really drastically changed only by the General Staff Order No. 8358-III of August 6, 1920, signed by the Chief-of-Staff, General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, modified three days later by special order No. 10,000, because the original plan fell into the hands of the enemy (the Bolsheviks seized a Polish officer ). Altogether, the orders contained a comprehensive counterattack plan from the south — from the Wieprz River, and from the north — from Modlin.

According to Piłsudski's own memoirs, this plan was his own. Of course, there is no doubt that he did not come up with it entirely alone, but with the help of his staff members, including, above all, General Rozwadowski who, as the Chief-of-Staff, was responsible for developing operational orders, and others who had been working on it since mid-July. But even if the idea itself did not come directly from the Marshal, it was he who made the final decision. The combined operation, calculated to break through to the rear of Tukhachevsky's army, depended on successfully stopping the enemy on the outskirts of Warsaw at any cost.

The counter-offensive plan was risky, because the Polish troops had to break away from the pressing enemy and reach the designated areas – especially those units assigned to the maneuver group gathering at the Wieprz River, which had to walk up to 200 km. There was also little time to prepare for the defense of the outskirts of the capital. [11]

Still from Jerzy Hoffman's Battle of Warsaw 1920 (2011) movie, with Daniel Olbrychski as Józef Piłsudski (Source: IMDb)

In the warfare, the Poles were indirectly helped by none other than Joseph Stalin himself. First, out of personal political interest, he arbitrarily blocked Tukhachevsky's order to Budyonny by delaying the march of the cavalry army north towards Warsaw for a full 17 days — officially to allow Budyonny to take Lvov first, but perhaps really to harm Tukhachevsky. And, in addition, he downplayed the intercepted original Polish plans of attack, thinking that it was just a clever attempt at deception.

The fighting near Warsaw was fierce and did not bring a solution right away. The fate of the battle hung in the balance near Radzymin. Although in the report to Moscow after the capture of Radzymin for the first time, it was written "White Poland is dying", the city, after bloody fights, passed from hand to hand several times, to be finally recaptured by the Poles on August 16.

The Polish plan of counterattack finally succeeded — and surprisingly well. Although Piłsudski's counterattack from Puławy hit again... into the void, but this time, it was not like when the Russians "disappeared" from Kiev.

It turned out that now the Bolsheviks were really fleeing in disarray and panic, leaving equipment and remnants of armament behind them. The surviving Soviet documents from August 1920 speak of "the withdrawal of the Red Army soldiers in complete disarray, which exceeded the wildest hopes that the Poles could have had." [15]

Tukhachevsky only realized the situation after a few days and ordered a retreat, but he was late due to the successes of the Polish army and its speed. The infantry advanced several dozen kilometers a day, occupying transport hubs, crossings and bridges in the rear of the retreating enemy.

As a result of the pursuit of the retreating Bolsheviks, the Polish army in the northern section stopped only at the currents of the Nemunas river. [4]

It is estimated that the Red Army lost around 25,000 in the Battle of Warsaw, be it killed, wounded, or missing, approx. 50 thousand soldiers were taken into Polish captivity, and 30 thousand were interned by the Germans (in Prussia). Polish losses amounted to 4.5 thousand killed, 22,000 wounded, and about 10 thousand missing. [11]

Battles of Komarów and Hrubieszów — the End of a Legend

Although, after winning the Battle of Warsaw, victory seemed close, it was not really the end yet. Let's not forget about Budyonny's legendary cavalry army, which was advancing towards Warsaw from the south, although somewhat delayed by Stalin's pettiness.

Fortunately for the Poles, it was not until August 17 that Budionny left Lwów after unsuccessful attempts to capture it and moved towards the Vistula. Then he lost some time again unsuccessfully trying to capture Zamość.

Until now, the retreat of Polish troops in this section was a series of battles and skirmishes, in which Polish forces, especially officers, were constantly melting away. But the enemy suffered losses too, and not only in combat. For example, many soldiers deserted from Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army and went over to the Polish side. Groups and entire units passed by. The deserters wanted to fight the Bolsheviks right away, so they were drafted into many regiments. [9]

However, Budyonny was moving towards Lublin. The troops of generals Haller and Sikorski finally forced him to fight them in the vicinity of Zamość and Komarów, taking the cavalry army into pincers, which threatened to encircle them. He was finally crushed near Komarów on August 31, 1920, where the largest cavalry battle in the Polish-Bolshevik war took place, which was a turning point on the southern front, comparable to the earlier Battle of Warsaw.

The Battle of Komarów was the largest cavalry battle since 1813 (Battle of Leipzig). The 1st Cavalry Division fought with two divisions of Budyonny's cavallry army, which were defeated, losing 2/3 of their personnel. The losses of the Polish side were about 300 killed and wounded (20% of the combat strength of the division) and 500 horses. [9]

Reenactment of the Battle of Komarów in Wolica Śniatycka in 2020 (Source: Wikipedia)

The final victory was decided by the charge of Captain Kornel Krzeczunowicz's unit, which galloped into the ranks of the enemy and have taken, among others, Budyonny's car. After a violent fight, the Soviets began to flee the battlefield. [9]

The combat strength of Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army was irretrievably broken in the war of 1920, although on September 1, after regrouping near Hrubieszów, it managed to decimate the 4th Infantry Regiment by surprise. Hrubieszów was liberated only on September 6, when Budionny withdrew further to the region of Włodzimierz Wołyński. [13]

After participating in the Bolshevik invasion of Poland, about 3,000 soldiers of the 20,000-strong legendary 1st Cavalry Army remained. [9] From then on, bled out and destroyed by previous fights, it no longer posed a great threat to the Polish front, and ceased to be a legend.

The Fall Campaign

Tukhachevsky, even after the Warsaw defeat, still believed in turning the tide of the war and wanted revenge. Thanks to reinforcements from the depths of Russia, his army again numbered over 100,000 soldiers and was to be ready to attack by the end of September.

Piłsudski was well aware of the importance of initiative and the lack of time. In order not to let Tukhachevsky regain his strength, he launched an advance on Grodno on 20 September, personally commanding two armies. The fighting was heavy and inconclusive until the Polish army, with an efficient maneuver, threatened the Bolsheviks with another encirclement. Tukhachevsky again had to flee.

The Poles reached the Daugava River and stopped 150 km from Kiev in the south. On October 12, Minsk was occupied, but Polish troops were soon withdrawn, on Piłsudski's order, due to the political situation. This is how the Polish-Bolshevik war ended. The armistice came into force on October 18, 1920, at midnight.

Peace Talks and the Treaty of Riga

It was characteristic of this war that peace talks continued almost throughout the conflict. Depending on the current situation at the front, one or the other side felt victorious and tried to dictate terms.

For example, on August 14, 1920 — hence, before the Battle of Warsaw was decided — a Polish delegation set out for Minsk, but they were presented with proposals unacceptable from the Polish point of view, because the Bolsheviks still felt victorious at that time.

The Poles demanded that the talks be transferred to a neutral ground, to Riga, where, in the limelight and in the presence of newspaper correspondents from all over the world, it was easier to conduct open negotiations. Unfortunately, the reluctant attitude of the Polish society towards the war at that moment, the reserve — bordering on reluctance — of the Allies, and the general hostility to Piłsudski's political ideas, also had an impact on them. To this day, there are disputes as to whether the military victory was well utilized then, and whether Poland could not have gained much more.

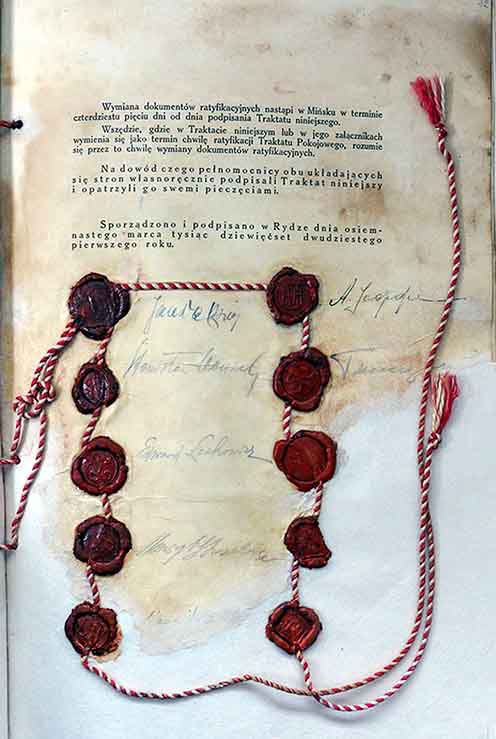

Document of the Riga Peace Treaty ending the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1920), archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (Source: Wikipedia)

Most of the negotiators from the Polish side in Riga belonged to right-wing parties opposed to the construction of a Polish-Belarusian-Lithuanian federation and the independence of Ukraine, i.e. Piłsudski's concept.

Still strong in Poland, although admittedly unrealistic, was the aspiration to subjugate the eastern borderlands as in the old days of the first Polish Commonwealth (Dmowski's incorporation concept), because the rule of the Bolsheviks in Russia was generally considered temporary, and the nationalist aspirations of Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians — as irrelevant. Unfortunately, the optimistic outlook on the transitory nature of the communist regime in Russia turned out to be illusory, and the nationalism of the Eastern Borderlands was quite real. [10]

Piłsudski's federal concept (left) and Dmowski's incorporation concept (right). (Source: IPN, modifications: A. Woźniewicz)

In mid-October, a preliminary agreement was concluded, and on March 18, 1921, a solemn peace was signed. This, so-called, Treaty of Riga ended the Polish-Bolshevik war, and both parties pledged "not to interfere in the internal affairs of the other state." [10] Apparently this clause was forgotten by Russia in 1939.

The treaty determined the location of borders between the states and regulated other previously disputed issues. The Polish delegation, dominated by supporters of the incorporation idea, gave the previously occupied territories to the defeated Bolsheviks essentially for free. The team member who pushed through the plan of relinquishing the eastern territories to the defeated Bolsheviks was Stanisław Grabski. He wanted to get rid of — as he put it — "Belarusian ulcer". [16]

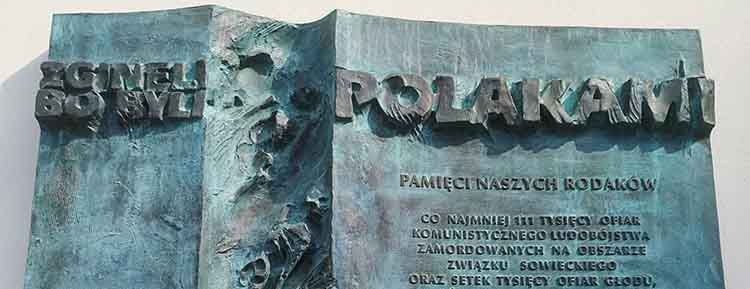

As a result, several million Poles found themselves outside Poland. According to the plan, the Poles were to be repatriated, but the Soviet authorities made it as difficult as possible. As a result of these reshuffles, just over a million people moved to Poland, two-thirds of whom were in fact Ukrainians and Belarusians. On the other side of the border, up to 2 million Poles remained at the mercy of the Bolshevik terror and became citizens of the Soviet Union.

Boundaries of Poland in 1793 and 1921 (Source: Wikipedia)

Already at the beginning of the actual talks in Riga, the Polish delegation recognized the communist Ukrainian SSR (the Soviet Ukrainian state) as a party to the negotiations, at the same time withdrawing its recognition for the UNR (led by Petliura), with which Poland was bound by the alliance agreement of spring 1920. It was then that Piłsudski's concept of creating a ring of buffer states separating Poland from Russia collapsed. [4]

Poland, exhausted by the war, could not, and the Polish government did not, want to continue fighting for Ukraine's independence, especially since the Ukrainians themselves did not support Petliura in 1920, and Western countries were opposed to Ukraine's independence.

The treaty also provided for the payment of 30 million rubles in gold, according to prices from 1913, to Poland as compensation for the contribution of Polish lands to building the Russian economy during the partitions, but these arrangements were never implemented by the Soviet side under various pretexts. It also obliged the Soviet side to return works of art and monuments looted during the partitions. However, little was returned.

On the Soviet side, the Treaty of Riga was regarded from the beginning (similarly to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) as "an ephemeral ceasefire forced by the military and political situation in the foreign expansion of the Soviet state to the west." [4]

To Poland, in turn, the Treaty of Riga potentially offered a chance to prepare for the future, inevitable conflict with Soviet Russia, which was unfortunately forgotten in the later years of the Second Polish Republic. [4]

On the part of the Western Allies, the Treaty of Riga was the result of forcing Poland to normalize relations with Russia. Poland was supposed to end the war in order to normalize economic ties between the West and Russia — this pattern is recurring today in the context of the Ukraine.

Where was the "Miracle"?

The term "Miracle on the Vistula" refers to the belief that Poland was victorious, especially in the Battle of Warsaw, as a result of some kind of miraculous, supernatural intervention. The battle turned the wheel of fortune, which, given the spectacular start of the Bolshevik offensive in July 1920, seemed indeed like a miracle.

The term "miracle" was first used by National Democracy politician and journalist Stanisław Stroński in Rzeczpospolita of August 14, 1920, begging for a miracle when the Bolshevik attack on Warsaw began. [11] By the way, this is the same journalist whose text "Remove this obstacle" unleashed a campaign in the conservative press and fueled the hatred of nationalists for the first president of the Republic of Poland, Gabriel Narutowicz, which resulted in his murder. [15]

The power of professor Stroński's talent and pen was so great that Polish society, thinking about the war with the Bolsheviks, thought more about the Kiev expedition than about the August battle. It thanked God for the August battle, and cursed Piłsudski for the Kiev expedition.

– Stanislaw Cat-Mackiewicz [16]

It was Piłsudski's opponents — after the fact — who picked up the term "miracle on the Vistula". This was intended to diminish the role of the Marshal's strategic craftsmanship.

Although August 15, when the fate of Radzymin was in the balance, is neither the beginning nor the end of the battle, it was also symbolic that the climax of the fighting near Warsaw fell on this day – on the Catholic feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was obvious to the Catholic Church and millions of believers that the Poles owed their victory to her intercession. [11]

When the tenth anniversary of the battle was approaching, Jerzy Kossak, the son of the famous Wojciech Kossak, to his father's despair — a self-taught artist, decided to paint "Miracle on the Vistula", an allegorical picture, in the genre of classic patriotic kitsch, inconsistent with the historical course of events, but full of symbolic meanings, where the defenders are supported by the Mother of God, and the hussars charge from the sky. It contributed to the spread of the myth of the miracle.

Miracle on the Vistula by Jerzy Kossak (1930) (Source: Wikipedia)

The supporters of Marshal Piłsudski were irritated by the term "miracle on the Vistula" because it was invented by their staunch political opponent. They perceived it as an act of disbelief in the Commander-in-Chief's competence and a desire to depreciate his success. Commander Piłsudski himself was sensitive to this type of "silly talk", in his opinion, diminishing the merits of the Polish soldier. "I know it's a metaphor," he thundered, "but damn such metaphors!" [15]

The slogan »miracle« was the first and most courteous attempt to deprive Piłsudski of the glory of victory

Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz wrote later. [16]

In turn, Piłsudski and his entourage strongly opposed emphasizing the merits of generals Rozwadowski, Weygand, Haller, or Sikorski, attributing all merit to the Marshal and leaving no room for any other heroes. [11]

Józef Piłsudski, Tadeusz Rozwadowski, Kazimierz Sosnkowski, 1923 (Source: CAW)

Reasoning in rational terms, especially in military ones, it must be emphasized that no miracle happened in August 1920. The Commander-in-Chief accepted a very good counter-offensive plan, the staff with General Rozwadowski at the helm developed it perfectly, and the Polish Army bravely and effectively implemented it. The skills of the commanders, the soldiers' will to fight, the work of radio intelligence, and the sacrifice of the entire nation for the defense of the state turned out to be of key importance. [11]

The radio intelligence was indeed the key. In fact, Piłsudski's plan could only succeed if the enemy's strategy was known. In this matter, the Cipher Section of the Office of the General Staff played an important role, which managed to intercept many messages that revealed the plans of the Russians. Poles had already broken Soviet codes much earlier, thanks to which they knew most of the enemy's orders. For example, Jan Kowalewski, a talented cryptographer who was then under 30 years old, distinguished himself in decoding Soviet ciphers. [15]

Not without significance was the war in the ether. During the Battle of Warsaw itself, having taken over one of the enemy's radio stations, for two days the Poles jammed Soviet radio communications, broadcasting passages from the Holy Bible, thus practically grounding two Soviet divisions cut off from command orders.

Aftermath of the War

Thus, a few days in August changed the dangerous Soviet bear into a panicky creature with its tail between its legs, a hunted animal, driven eastwards beyond the Nemunas and further — although hunted, but still alive and breathing hatred until today. And this war, which lasted for more than two years and covered 60% of Poland's territory, destroyed everything that the armies fighting for four years in World War I had failed to destroy.

Zdzisław Jasiński, Allegory of Victory in 1920. Warsaw ahead, National Museum in Warsaw, public domain. (Source: IPN)

In the war with the Bolsheviks, the fate of free Poland hung in the balance. A brilliant counter-offensive, mobilization of the society, but also the mistakes of the Bolsheviks, made it possible to push aside the specter of communist Poland — albeit only for 25 years. Poland emerged from this war free and independent, but ruined.

The Bolsheviks not only failed to capture Warsaw, but also did not move further west. Lenin's vision of engulfing the whole of Europe in revolution lay in ruins. But the young independent Poland that stopped them was itself in ruins.

The victory, paradoxically, gave rise to new political disputes among Poles. There was a fierce argument (and it continues to this day) about who was the architect of the victorious Battle of Warsaw. And not all Poles could consider the signing of the Treaty of Riga a happy ending. There was even talk of "betrayal". The reason was simple: Poland relinquished part of its territory and its population in the east. [16]