Fought August 13-20, 1920 between the armies of the newly restored Poland and revolutionary Bolshevik Russia, this great battle is also known as “the Miracle of the Wisła,” or Vistula, Poland’s main river. Pitting two armies totaling over 250,000 combatants, the battle resulted in the Bolsheviks’ total defeat. As to its significance, Britain’s ambassador to Germany, in Warsaw at the time, would call it “the 18th most decisive battle in world history.” Why was this Battle fought? Why was it so important?

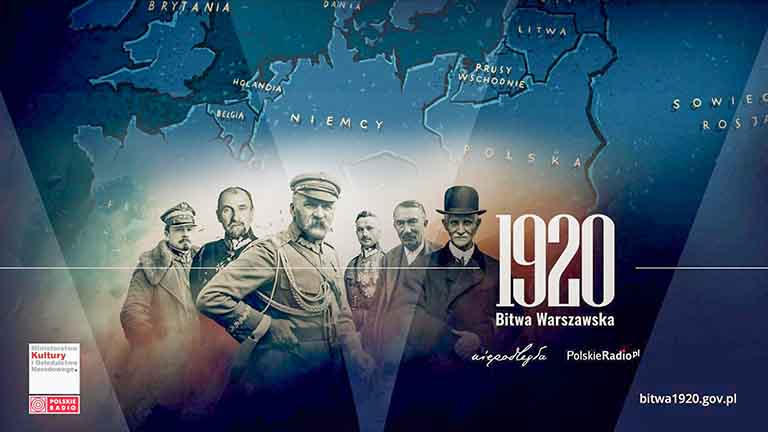

Graphic promoting a portal dedicated to the 1920 Battle of Warsaw (Źródło: bitwa1920.gov.pl)

On November 11, 1918, the very day the First World War ended with an armistice or truce in the trenches dividing Germany and France, General Józef Piłsudski proclaimed Poland’s national rebirth in Warsaw. This came after 123 years of occupation by the empires of Russia, Austria, and Germany. But proclaiming independence was one thing, making independence a reality and successfully defining its borders were very different matters. Indeed, it would take the Poles more than two years of difficult negotiations along with plenty of fighting to accomplish these gargantuan tasks. For his part, Piłsudski believed that for Poland to survive, it needed to include the lands to the east that had been part of the old Polish Commonwealth going back to 1772. It was in that year that Russia, German Prussia, and Austria had seized a third of the country in what became known as the first partition of Poland, the first giant step in the country’s destruction in 1795.

However, these eastern lands were inhabited mainly by non-Polish peoples – Ukrainians, Belorussians, and Lithuanians – with ethnic Poles comprising just 35 percent of the population. Still, Piłsudski believed these nationalities could be persuaded to be part of a new, federalized Polish state and, in that way, be liberated from the oppression they had endured under Russia – whether it was the Russia of the tsars, or that of their new Bolshevik revolutionary successors led by Vladimir Lenin who had seized control of the empire in 1917. Indeed, by 1919, Poland had become embroiled in a worsening border conflict with the new and radical regime in Moscow.

By Spring 1920, Piłsudski had given up the idea of a restored multi-ethnic Commonwealth. Instead, he made an agreement with the head of the latest Ukrainian national government in Kiev headed by Symon Petlura that aimed at guaranteeing Ukrainian independence from Soviet Russia. But, in response, an infuriated Lenin then ordered the mobilizing of a new and massive Bolshevik army to regain control of the Ukraine. Furthermore, he created a committee of Polish Bolsheviks under Feliks Dzherzhinsky (Dizerżyński), who had organized the ruthless CHEKA special police force to secure the revolution in Russia. Dzherzhinsky’s group’s mission was to follow the Red Army in its invasion of Poland, unseat Piłsudski, and establish a puppet state subservient to Lenin.

As quickly as the Polish army had moved into Kiev in May 1920, just as quickly was it driven westward back into ethnic Poland. By the end of July, the massive Red Army commanded by the 27-year-old Mikhail Tukhachevsky was approaching Warsaw itself. Incredibly, this war had exploded into a conflict that pitted over a million Bolshevik troops against about 750,000 Poles in a true fight to the death. In this war infantry, cavalry, tanks, armored locomotives, even airplanes, would all see action.

By July Poland was in a panic, its forces in seeming disarray. Piłsudski, the great hero in May, was now condemned by his critics in Warsaw as the gravedigger of independence. Poland found itself abandoned by its supposed allies, France and Britain. But Piłsudski kept his head. He appointed Wincenty Witos, the popular leader of the Peasant party to be Prime Minister and called on him to rally the country’s vast peasantry to the nation’s defense. In response countless thousands of peasant farmers joined patriotic urban workers in the fight for Poland’s survival.

Red Army in 1920 (contemporary re-enaction) (Source: Wikipedia)

As the Bolshevik army neared Warsaw, Piłsudski got a lucky break when Polish cryptographers got hold of Tukhachevsky’s plans. Piłsudski himself devised the strategy to defeat the massive invasion. Essentially his plan was to lure the Bolsheviks to attack the defenders of Warsaw from the east. As the battle commenced, he then ordered most of his troops to wheel around from the south in a massive sweeping action against the invaders’ left flank. The plan worked. The Reds were totally surprised and thrown into panic. Of the 130,000-man army, over 20,000 were killed, 65,000 were captured, and another 35,000 were forced to flee into East Prussia where they were disarmed. In the Battle, the Poles lost about 4,500 men.

Just two weeks later, the remaining Red army forces under Cavalry Commander Semyon Budyonny and Josef Stalin were also crushed. By October, Lenin was forced to call an end to the fighting. The Bolsheviks were forced to wake up from their dream of a victory over the corpse of the Polish ‘landlord state” and propelling the revolution into war-wrecked Germany itself. In March 1921, Poland and Russia reached a border settlement at Riga in Latvia. In it, Poland gained some Ukrainian and Belarussian lands to the east. But most of the Ukraine and Belarus was lost to the Soviet regime. Their peoples, including the Polish minority that chose to remain outside of Poland, would go on to suffer in horrific fashion in the years to come.

Josef Stalin was one Bolshevik who never forgot the debacle of 1920. As Lenin’s successor, in 1937 he ordered the execution of Tukhachevsky, a leader he hated. In August 1939, he and Adolf Hitler conspired to divide Poland between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany as part of a pact that led to World War II just days later. In April 1940, he got more revenge in signing the death warrants for 24,000 captured Polish military officers and civic leaders thus perpetrating an incredible (and long denied) war crime known as the Katyn Forest Massacre.

The battle of Warsaw was indeed a miracle in that the victory saved the new Polish republic in 1920. Lenin’s dream of making victory over Poland the steppingstone to a violent European-wide revolution was also shattered.

With the victory, Piłsudski’s stature rose dramatically. However, his political enemies remained unreconciled to him. In 1926 he did lead a coup against the government and established a regime of national moral reform (“Sanacja”). It would survive his death in 1935, only to be destroyed by the Nazi-Soviet invasions of 1939.

The monumental victory at Warsaw in August 1920 was thus not the “end of the story”. But it did allow the citizens of a reborn Poland to experience two critical decades of independence.