Agnieszka Wisła, her life, activity and dedication are inextricably linked to the difficult, painful but successful process of regaining independence by Poland.

Do Poles today remember about the huge sacrifice and participation of the American Polonia to make Poland appear again on the world map as a sovereign and independent state? It is difficult to answer this question today. The rapidly changing geopolitical reality brings many new and unfavorable circumstances for our homeland, which make us reconsider the fate of Poland.

In this context, it is worth knowing the history and profiles of people who sacrificed so much to make Poland independent and sovereign.

Born in 1887 in Poland under Prussian rule, Agnieszka Wisła was brought up with respect for Polish and patriotic values. As a young girl, motivated by the lack of freedom of speech in the territories under the administration of the Prussian partition, she decided to leave for the United States. It was 1906. At that time, the largest foreign concentration of Poles was in Chicago. Agnieszka joined her sister and brother-in-law who already lived in the city.

After the outbreak of World War I, hopes for regaining Poland's independence were also revived among American Polonia. Motivated by this hope, Agnieszka Wisła joined the ranks of the Polish community organization called the Polish Falcons Association in America in 1914. It was an organization that continued the traditions of the "Sokół" (Falcon) Gymnastic Society operating in Poland.

Agnieszka Wisła (in the middle) with two Sokolice paramedics. (Source: AZG SWAP)

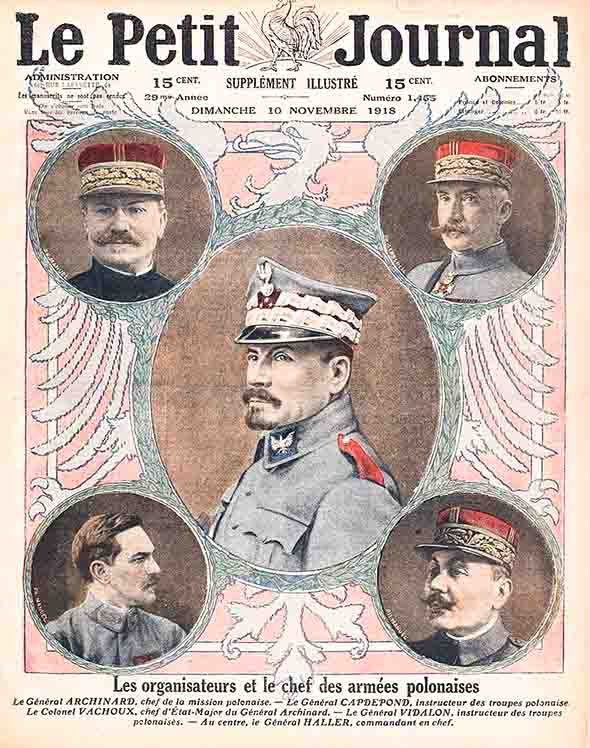

After a period of cultural and educational activities and work to promote physical culture among the members of the organization, the girls from Sokolstwo (Falconry) focused on preparing for possible sanitary service in the areas of military operations. It made sense, because the long-awaited moment of establishing the Polish Army in France soon arrived, pursuant to the decree of the French President Raymond Poincaré of June 4, 1917. It was the culmination of the initiative of Ignacy Paderewski, as well as Roman Dmowski and the Polish National Committee headed by him.

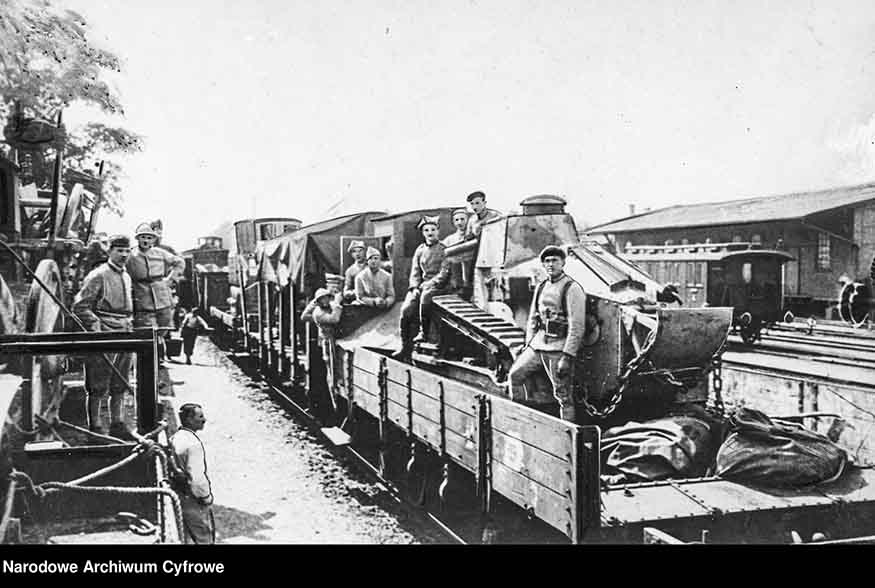

In September 1917, the Canadian government organized a training camp on its territory for volunteers from North America and also from Brazil. These were the beginnings of the famous Blue Army, also known as Haller's Army, the Polish volunteer military formation.

From the very beginning, Agnieszka Wisła was actively involved in the recruitment process of volunteers for the newly established Blue Army (so called because of the color of the uniforms). Agnieszka and her friends "Sokolice" urged volunteers of Polish origin who were not required to serve in the US military to join the ranks of the Polish army. This action had a wide resonance mainly in such cities as: Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, New York, Bridgeport and Boston.

Agnieszka Wisła took part in the official opening of the training camp in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada. She made a banner with her own hands: "FOR UNITED AND INDEPENDENT POLAND!", which she handed over to the Polish Army in France on October 14, 1917 on behalf of Polish women from America.

Agnieszka Wisła presenting the banner she made for the Polish Army in France. (Source: AZG SWAP)

More than 21,000 volunteers of Polish descent have traveled to Europe from North America since 1917 to fight in the ranks of the Polish Army, first in France, and then in reborn Poland, on the eastern border, against Ukrainians and Bolsheviks from Russia.

The soldiers of the Blue Army were supported by material and monetary donations from the self-sacrificing Polish American community. Agnieszka Wisła not only organized fundraisers to support this aid, but also provided the soldiers at the front with sweaters, scarves and other warm clothing made by women from Polish organizations.

After the United States entered World War I, Agnieszka Wisła tried to join the American Red Cross. However, this was not possible, as she was not yet a US citizen at the time. The situation of Agnieszka and Polish women in a similar position in the USA was understood by Helena Paderewska, Ignacy Paderewski's wife who supported him in his patriotic activities.

Thanks to her efforts, the Polish White Cross, a civilian organization operating for the army, was established. Agnieszka Wisła took part in the training of nurses organized by Helena Paderewska. After the training, Agnieszka Wisła, together with a group of 42 other nurses, left for France in 1918. There, she took care of Polish soldiers wounded in warfare. First, in hospitals in Paris, and then, in the south of France, where she helped Polish soldiers who were there recovering from injuries sustained at the front.

Nurses of the Polish White Cross with patients in the hospital at Dzielna Street in Warsaw, 1919. (Source: AZG SWAP)

In November 1918, after 123 years of absence from the political maps of Europe, Poland regained its independence.

In May 1919, after the end of the war in Western Europe, Agnieszka Wisła, together with Ignacy Paderewski, his wife and other personalities, left for Poland by diplomatic train.

Unfortunately, contrary to hopes, these were not peaceful times for the new Republic. In 1919, Soviet Russia intended to implement the ideas of the communist revolution by force throughout Europe. It started with Poland. The Polish-Russian war began. The issue of Poland's access to the sea was in the balance, and the Greater Poland and Silesian uprisings broke out. The Republic of Poland had to defend its independence.

The Blue Army came to Poland in 1919 and was the best equipped part of the Polish army. Full of enthusiasm and bravery, the soldiers of this Army signed up memorably in victorious battles with the troops of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Its advances beyond the Zbruch river were possible thanks to Haller's soldiers and his personal involvement. There was intense fighting on the Eastern Front against the Ukrainians and Russians. This is where Agnieszka Wisła, who recently arrived in the country, was sent. At the front, she took care of wounded Polish soldiers and took care of giving them material gifts still being sent by the American Polonia.

Agnieszka Wisła recalls it as follows:

In April 1919, I left with this army for Poland, where I went through the entire Bolshevik invasion on the fronts: Ukrainian - Lutsk, Rivne, Sarny, Rokitno; later the Russian front, Vilnius, Dźwińsk, Minsk, Borisów, where I delivered medicines, warm clothes, cigarettes and other things sent from America and other countries for soldiers on the fronts of the fight against the Bolsheviks, because after Poland was deprived of freedom in 1918, it was so exhausted, that soldiers fought in paper clothes, in many cases legs wrapped in rags instead of shoes, and wounds wrapped in papers.

During this twenty-two months of hard work in Poland, and especially during my stay on the Volhynian and Lithuanian-Belarusian fronts, I had to deal with such poverty, misery, diseases and various kinds of extraordinary accidents that in normal life it would be impossible to believe that a human being could live in such conditions.

After returning from the front, Agnieszka Wisła delivered war convalescents to Polish manor houses in the countryside. Soldiers were received there by self-sacrificing civilians.

Gifts from America continued to pour in. Agnieszka Wisła dealt with their delivery to those in need. These were mainly medicines, medical equipment and material aid.

At the beginning of 1920, Agnieszka was delegated to Pomerania, which was being taken over from the Germans. There, she set up inns and community centers at military schools educating the staff of the Navy, airmen, navigators and artillery non-commissioned officers.

It was August 1920 and the time of the famous defense of Warsaw from the Bolsheviks. Agnieszka Wisła went to the capital between August 12 and 18 and helped in rescuing the wounded.

She did it against the instructions of the president of PBK, Helena Paderewska, who released the ladies from the obligation to serve the wounded during the bloody battle for Warsaw and ordered them to move to a safe place.

From Agnieszka Wisła's memoirs:

During the siege of Warsaw, I was there for a whole week and seven of us Polish women from America received an order from our manager Helena Paderewska to leave Warsaw immediately. We did not obey this instruction, for which I later received a letter from her stating that, for the first time in her life, she was forced to bow her head against the insubordination of her subordinates.

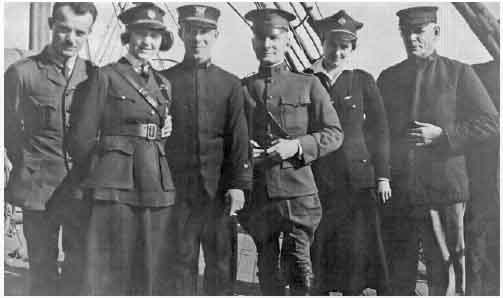

After the defense of Warsaw, Agnieszka Wisła returned to Pomerania and stayed there until January 28, 1921. Then, together with demobilized soldiers of the Blue Army, she set off from Gdańsk on the ship "President Grant" to New York. They arrived on American soil on February 16, 1921.

PBK orderlies Agnieszka Wisła (second from the right) and Anastazja Wichniarek on board the "President Grant", 1921 (Source: AZG SWAP)

Only then did the really difficult times begin. Out of 21,000 volunteers from America who joined the Polish Army in France during World War I, about 14,000 returned to the USA. Most of them were not citizens of the United States and did not fight in the American army, therefore they did not obtain any rights to receive assistance and care, even as war veterans.

There was a bitter disappointment and a brutal collision with reality. Demobilized soldiers of the Blue Army, who fought with sacrifice for the independence of Poland, were out of work after several years of absence, often lost their families, many of them were crippled as a result of wounds sustained at the front. They had no money, no homes, no welfare. They were solely relying on self-help.

This is one of the most painful chapters in the history of Polish Americans. The newly reborn Poland was not interested in their fate. They did their thing. The independence of the homeland has been regained.

Agnieszka Wisła remained faithful to the demobilized soldiers of the Polish Army who returned to the United States. She never ceased her efforts to improve their situation.

In May 1921, at a convention in Cleveland, Ohio, an organization was created under the name "Polish Army Veterans Association in America" (Stowarzyszenie Weteranów Armii Polskiej, SWAP), which set itself the goal of helping numerous veterans of the Blue Army, in particular invalids, homeless and unemployed.

Agnieszka Wisła was actively involved in organizing fundraisers as part of the association for veterans fighting in Europe for Poland's independence.

She was the first woman accepted into the SWAP ranks in America. In 1922, she organized the Veterans Aid Committee, which brought together women of good will who supported veterans of the Polish Army.

In the fall of 1923, the Main Board of SWAP decided to establish a unit called the Auxiliary Corps at the Association, which began its activity in Milwaukee in order to provide material and psychological help to Polish veterans.

In the United States, the time of the great economic recession was emerging gradually and inevitably (especially in the second half of the 1920s). Unemployment, stock market crash, general poverty and hopelessness of everyday life resulted in growing indifference to the fate of former soldiers of the Haller Army fighting in Europe for Poland's independence.

Agnieszka Wisła and activists of the Auxiliary Corps in Chicago made efforts to create a shelter for veterans. They were assigned an abandoned house on Emma Street in Chicago. They maintained the shelter from charitable contributions. Later, more shelters were established in other states. There, one could meet disabled, sick and desperate veterans who devoted their best years in the fight for regaining independence of Poland, in which they did not even live. Attracted by promises and adored by the American Polonia, they joined the Polish Army and went overseas as young, able-bodied men motivated by the patriotic idea of fighting for a just cause.

Agnieszka Wisła before leaving for America, Toruń, January 1921 (Source: AZG SWAP)

Upon returning to the US, bitter disappointment followed. Only a few representatives of the Polish community (including Agnieszka Wisła) continued to support them to the best of their modest abilities. The Republic of Poland has completely forgotten about them.

The soldiers sent overseas, veterans of the Polish Army, defenders of the independence of the Republic of Poland, returned to America in a deplorable physical and mental state. They were exhausted, hungry and lice infested. Some of them were sick with typhus. They had no money, no future prospects. They felt a sense of duty well-done, and bitterness that it was not appreciated in any way.

Does Poland remember their great sacrifice today?

Polonia made a huge effort, sacrificing the lives and health of tens of thousands of its young representatives, who, guided by romantically understood patriotism, fought for the independence of a country in which they did not even live.

The American Polonia supported not only the soldiers of the Polish Army established in France, but also sent gifts to the civilian population in Poland. Has it ever been appreciated? Do young people in Poland learn about it?

Agnieszka Wisła gloriously stood out from people who no longer cared about the fate of the Blue Army volunteers fighting in Europe for Poland's independence. Being one of the people who strongly urged young Poles from the United States and Canada to join the ranks of the Polish Army, she felt responsible for their disability acquired at the front and further, often tragic and humiliating fate condemning them to poverty, homelessness and helplessness.

Agnieszka Wisła talks about her activities in this difficult time:

I consider it a great duty to work for a former soldier of the Polish Army, who lost his health on behalf of the entire Polish emigration and for whose deeds many of its leaders received many awards and decorations, because I do not want to be, like others, that ungrateful one who promised a lot, when he recruited them, and then completely forgot them.

For her faithful attitude, hard work and continuous efforts aimed at improving the situation of veterans of the Polish Army in the fight to regain and maintain the independence of the Republic of Poland, Agnieszka Wisła deserves the highest respect and recognition. Thank you!