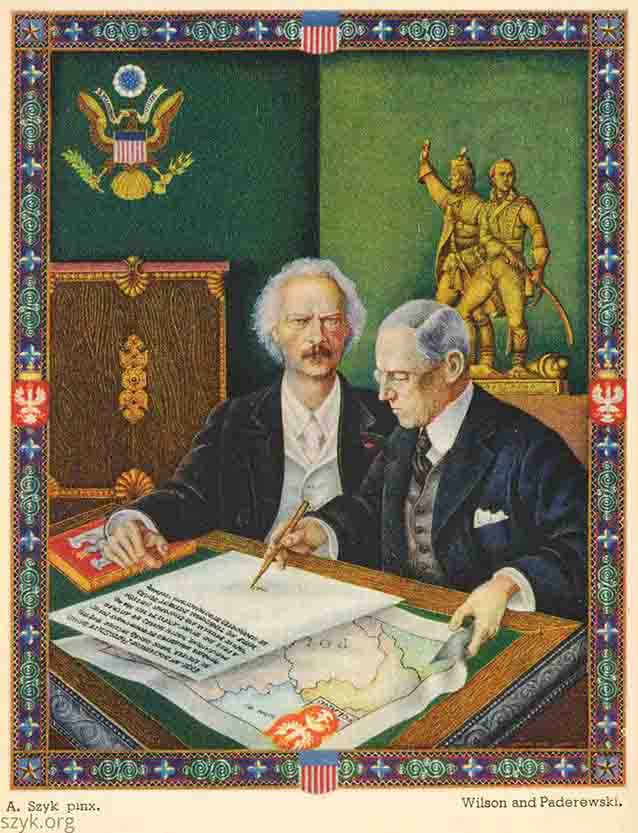

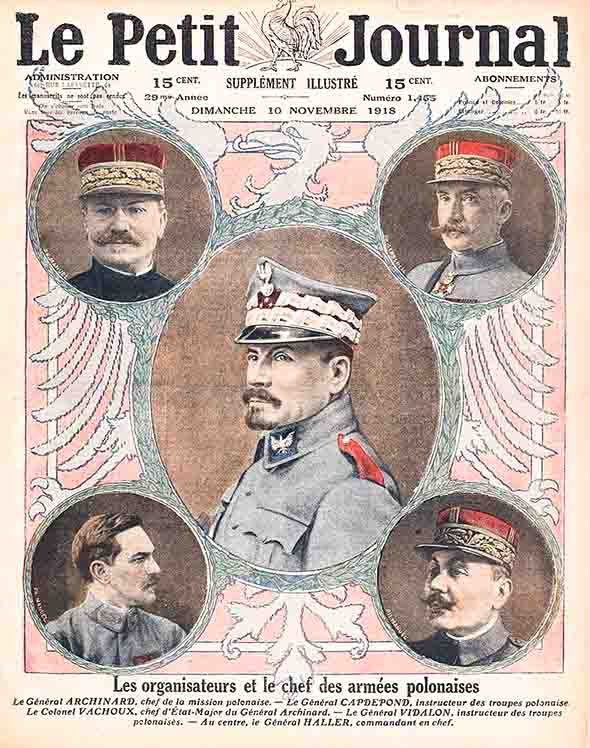

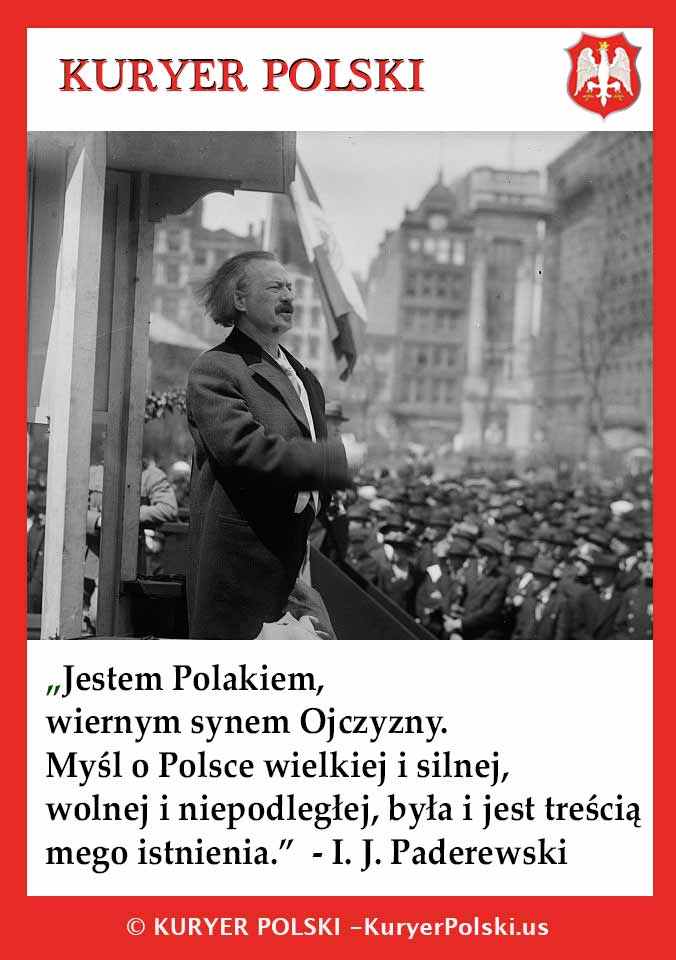

During World War I, the political direction for Polish emigration was simple - Poles should co-operate with the Entente [countries]. After many meetings with government officials, special hopes were placed on the Canadian government, which agreed to accept a group of Falcons into the Toronto military school. On January 1, 1917, 23 candidate officers secretly arrived in Toronto. On May 21, 1917, they received officer ranks. The top five became instructors at the Cadet School in Cambridge Springs. It was a breakthrough in the creation of the Polish army. As early as March 19, 1917, in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, in place of the two-month paramilitary courses that had been held since 1914, the Cadet School was established, which prepared NCOs and officers for the Polish army. The training was at a high level. The best specialists were educated at the officer school in Toronto, Canada. On April 1-4, 1917, the Extraordinary Congress of the Falcon Association was held in Pittsburgh, at which I.J. Paderewski spoke. At that time, the United States was already engaged in the war against Germany. Honorary Falcon - Master Paderewski - took up in his speech the idea of organizing a Polish army of 100,000 and naming it "Kościuszko Army". Despite fierce criticism of the "unfortunate and ridiculous idea of an artist who does not completely understand the principles of statehood", dreams of the Polish army became reality. On June 4, 1917, French President Raymond Poincare issued a decree establishing an autonomous Polish Army in France. Initially, its ranks were joined by prisoners of war from the Austrian army and volunteers from the Polish community in France. General Louis Archinard was appointed its commander in chief. France agreed to uniform and equip Polish soldiers. They were assigned a bright blue uniform, which was why they were called the "Blue Army". New uniforms and equipment: tanks, planes, engineering equipment, were then the latest weaponry and became the nucleus of new types of troops in the Polish Army. However, little is said about this in Polish historiography.

Polish emigration creates the foundations of Polish statehood and diplomacy.

Polish military eagle

On August 15, 1917 in Lausanne, Roman Dmowski establishes the Polish National Committee (Komitet Narodowy Polski, KNP), whose aim was to rebuild the Polish state with the help of the Entente countries. The KNP was recognized by the governments of France, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States as a substitute for the government of the reviving Polish state and representing Poland's interests. KNP pursued foreign policy and organized the Polish Army in France. A special Military Mission was also created aside from the Committee, which was to agree with the Entente governments on the legal conditions on which the Blue Army was to operate. The American Polish diaspora worked closely with the Committee. It was the diaspora that provided transfers for the financing of the Polish National Committee in Paris, over 16 million dollars were collected then, which translates into about 400 million dollars today.

Soon a recruitment campaign for the Polish army started. Everywhere where there were larger Polish communities, especially in the United States and Canada, passionate appeals showed up:

INTO THE RANKS! TO ARMS! TO FIGHTING! GRAB A WEAPON! FIGHT FOR POLISH FREEDOM!

The Association of Falcons in America called an Extraordinary Rally, attended by a representative of the Military Mission from France, a well-known writer, Lieutenant Wacław Gąsiorowski. After his passionate patriotic speeches, falcon military commissions were appointed to organize the recruitment. These committees developed detailed guidelines for volunteers joining the army. They appointed 12 District Recruitment Centers. Center No. 1 was in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Center No. 2 in Chicago, and another in New York, Boston, and other larger Polish diaspora centers. Organizational work, thanks to the great commitment of the Mission and volunteers, went very smoothly. The United States agreed to recruit, and Canada granted a rally camp site in the border town of Niagara-on-the-Lake. Volunteers started pouring in quickly.

On November 4, after a solemn mass, the Camp was consecrated and a banner with the White Eagle was placed over it. Then there was a parade in which the columns of the future Polish Army marched saluting the banner. Those moments were described as follows: "The mood was solemn and serious, when these columns marched ahead of us, everyone was aware that this was a historic moment in the life of the Polish nation." On November 21, the camp was visited by Master Paderewski who delivered a short speech, which he concluded with words:

I am happy to see you in this row, because I see it as an announcement of a Polish victory. Your homeland demands great sacrifices from you, but a great reward awaits you, because the freedom and independence of a united Poland depend on your courage. Go with faith in victory, and may the Highest God keep you and bless you.

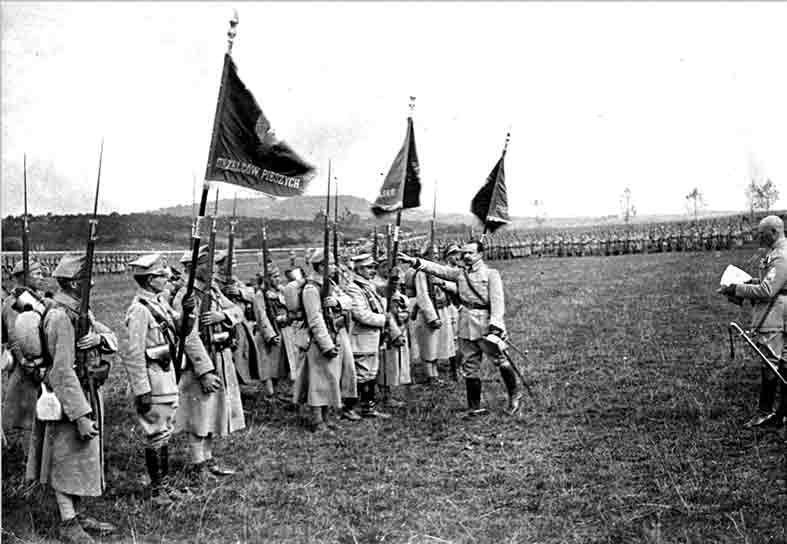

Volunteers from America

The recruitment process in the first days was very enthusiastic, not to say explosive. Even the descendants of Poles who had come to America joined the formation. Some have never known the country of their fathers before.

After only two weeks, the training camp at Niagara-on-the-Lake was overcrowded to the point that the commission temporarily suspended volunteers. In November, nearly 3,000 were stationed in the camp, designed for 500-600 soldiers. Winter was approaching and the climatic conditions were rather not conducive to living in tents. Organized legions of Polish women started sewing works to provide volunteers with warm clothes, sweaters, scarves, socks and gloves. The event was under the patronage of the Master's wife, Helena Paderewska. After the Commission's long efforts, the American government made Fort Niagara available on the other side of the border for Polish needs. This temporarily resolved the housing problems and recruitment could continue.

Polish recruitment poster by Władysław T. Benda

On December 28, 1917, the first transports of volunteers from the United States reached the Polish Army in France. Thousands of volunteers waited for the next ones in the training camps, and the recruitment campaign, thanks to the involvement of artists and the Polish press, spread more and more. The graphic artist Władysław Benda was particularly famous in the propaganda campaign. Everyone knew his posters, and today he is identified with them. The recruitment was finally completed in February 1919. On March 11, the last Polish volunteers left the Niagara-on-the-Lake camp. From the detailed report of the camp commandant, Colonel Le Pan, we learn that: 20.720 soldiers went to France. 1004 were released due to poor health, 129 were released due to the need to provide for their family, 91 were sent back for various other reasons, and 41 died in the camp (Spanish flu).

Recruitment was taking place in the Polish communities, and in Paris, the National Committee made sure that the formed army was truly Polish, with a Polish eagle, a Polish command and a Polish commander. On its anniversary, the Blue Army received banners from the French cities of Paris, Nancy, Belfort and Verdun, and the soldiers recited the oath:

I swear before the only God Almighty in the Trinity, to be faithful to my homeland, one and indivisible; I swear that I am ready to lay down my life for the holy cause of its unification and liberation, to defend my banner to the last drop of blood, to keep discipline and obedience to my military authority, and to protect the honor of the Polish soldier with all my conduct. So help me God.

Roman Dmowski and the French military commanders took part in the ceremony. After the ceremonies, the soldiers went into trenches, and then took part in the fights in which the first soldiers and officers were killed. The first list includes 108 names. It is not known how many died before such lists were compiled. Joy, enthusiasm and hope faced death for the first time. At the same time, there were disputes in the circles of political leaders about the shape and forms of acting for the Independent [country].

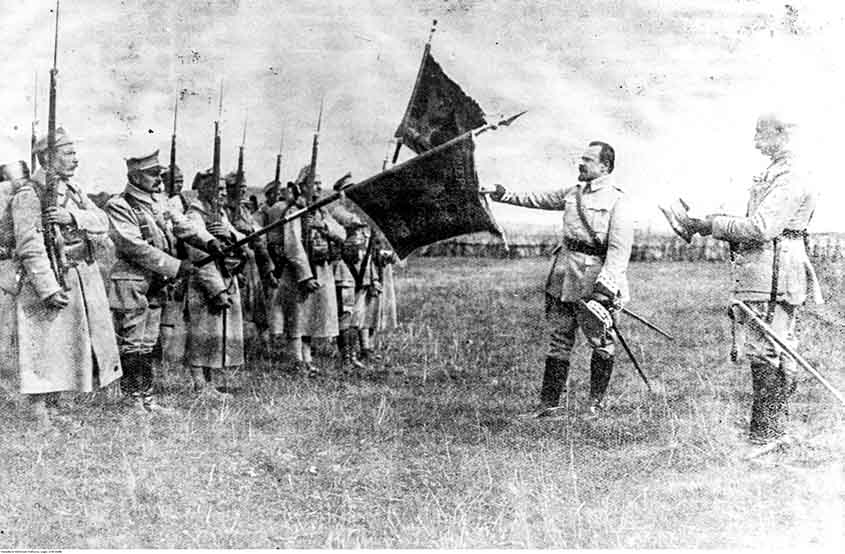

On July 13, 1918, after the refusal to swear allegiance to Austria, after a ten-day odyssey by Karelia and Murmansk, the legendary leader of the Polish falconry in Poland, the commander of the 2nd Brigade of the Legions, General Józef Haller, reached Paris. He immediately joined the work of the Polish National Committee, which first entrusted him with the chairmanship of the Military Mission, and on October 4, 1918, after diplomatic efforts in the command and the French government, he was formally entrusted with the command of the Polish Army being formed. The combat strength of this army at that time was a division, about 10,000 soldiers. When the Blue Army entered Poland, it numbered about 70,000 soldiers, including 35,000 former prisoners of war from the Austro-Hungarian army, about 22,000 from the Polish diaspora (including 1,000 from Milwaukee and 3,000 from Chicago). On October 9, General Józef Haller, taking command, swore allegiance to Poland at the banner. The division did not manage to enter the fighting on the Western Front, because the war ended on November 11 for the world. It continued for Poland. It was necessary to establish the state borders by force, both in the East and in the West. The Polish Army was needed, desired and expected by Poland. Meanwhile, France was reorganizing its troops and eagerly getting rid of the "allies" on its territory and helped to send the Polish army to Poland. Transport and the route through Germany caused difficulties.

The swearing in of general Haller

Return to Poland

Finally, on April 4, 1919, an agreement between the French and German governments was signed in Spa (Belgium), transit lines were marked, General Haller issued the appropriate orders and the evacuation of the Blue Army to Poland began. The order to return from April 15, 1919 was:

The longed-for moment has come for the Polish Army to depart from Italy, France and America to Poland. Just like a hundred years ago, today we are returning to Poland, happier than the others ... Polish Divisions, created in foreign lands by the efforts of the entire Polish nation, and especially thanks to the courage and bravery of its emigration in both Americas, North and South, are going to Poland; thanks to the persistent work of Polish statesmen, such as Ignacy Paderewski and Roman Dmowski, thanks to the armed deeds of the Head of the Republic of Poland, Józef Piłsudski

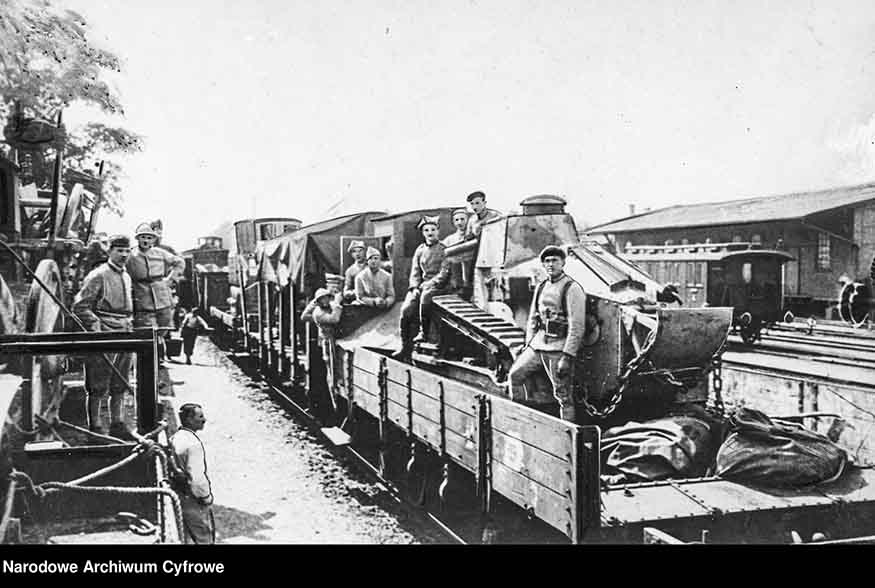

Equipment with a small amount of protection traveled in sealed carriages, soldiers, provided with provisions for 8 days, in separate carriages. The first transport left on April 16. The last of 383 trains arrived in Poland in mid-June. Of course, the journey was not without harassment and difficulties in Germany, but the Polish population welcomed the blue soldiers with flowers, Easter breakfast and joy. After all, it was the first real Polish army since the November Uprising [1830].

General Haller arrived in Warsaw on April 21, 1919. He was greeted like a national hero, and the magistrate granted him the title of an honorary citizen of the city.

The Blue Army was, at that time, well equipped and trained. It had 120 tanks, 98 aircraft, engineering troops, instructors, cavalry, artillery, communications troops, 7 field hospitals and very high morale of soldiers. Already in May, it was directed to the eastern front, the front of Polish-Ukrainian fights, the greatest threat from Soviet Russia. General Haller fought for the same Polish cities for which he fought as the commander of the 2nd Legionary Brigade. Through Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, he reached the line of the Zbrucz River with his 'Blue'. He had to face the cruel cavalry of Semyon Budyonny.

The Blue Army and Politics

Despite strategic successes, or perhaps because of them, the Blue General did not find recognition from the Chief of State. He remained in opposition to the ruling camp until the end. In June 1919 he was recalled as the commander of the Blue Army and directed to the Polish-German border in order to take command of the South-Western Front. Under a different, ever-changing command, the Hallerans felt abandoned and disappointed. A lot of regret can be read in the front reports of Lt. Col. Tadeusz Kurcjusz, a Polish volunteer from America, chief of staff of the 13th division. The reports cover the period from January to June 1920. The division was gradually relegated to a secondary role. Finishing his memoirs, Lt. Col. Kurcjusz bitterly writes: “At that time, the new division commander, Colonel Paulik, came to Kordylewka. With his arrival, there were no changes to the way of command. He still left the staff a free hand to issue orders on his behalf. (…) Still, the concern for conducting activities falls entirely on me and sometimes it was extremely difficult for me to make decisions on my own, not believing or knowing my commander and his thoughts of the maneuver. (...) The strategic goal of the expedition has disappeared, and the political goal has remained.

On September 1, 1920, the Blue Army was completely disbanded. Individual formations became part of other domestic military units. Volunteers from the United States were demobilized, which irritated the American Polonia. The number of demobilized Hallerians was estimated at 10,000 to 12,000 in February 1920. The situation of the demobilized soldiers of the Blue Army was very bad. The matter was discussed at the highest levels of US government. Julius Kahn, Congressman from California, and Congressman Kleczka, from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, took care of it. The issue of the return of demobilized volunteers was raised in the House of Representatives at the beginning of 1920. The Chamber authorized Secretary of War Baker to transport demobilized Hallerans - also American citizens - on American transports. These were to be supply ships for American soldiers stationed in the occupied Rhineland. The soldiers demobilized at different times waited for transport in the overcrowded camps in Skierniewice and Grupa near Grudziądz. The first ship, for which the demobilized Haller citizens were waiting, entered the Gdańsk port on March 19, 1920. It was the USAT ANTIGONE freighter. 1168 veterans were boarded on March 28. Prior to departure, the American Red Cross health services performed a health check and carefully deloused the veterans. The next transport of POCAHONTAS took 1,705 veterans. Both transports reached New York at the end of April 1920. The seventh shipment arrived on August 12 that year. The last one on February 16, 1921. American Red Cross observers then reported that that Poland gave its defenders in a very bad physical and mental condition, emaciated, hungry, lousy, without money, without underwear. By the time the first ship reached Antwerp, the first cases of typhus were recorded among the soldiers. The arrival of the Hallerans 'shipment to the US made the US authorities quite consterned, as the veterans' ID cards turned out to be worthless, as they contained neither photographs nor fingerprints. There was great fear that Bolshevik agents might be among the returnees. British intelligence informed its allies that some Hallerans, before leaving Gdańsk, had received offers to sell their documents for $ 1,000, huge for those times. However, no spy could be identified. In total, 12,546 Hallerans returned to the States. The returnees had to be provided with a stopping place before going home. The military camp at Camp Dix, New Jersey, was such a quarters for returnees. After diplomatic talks with a representative of the Polish community, Jan Smulski, the Polish Legation agreed to finance the costs of staying in the camp, a train ticket to the place of residence and pay each private for $10 and the officer $20 a one-time allowance. The Polish National Department (the Polish community fund) paid each private $15, and the officer $30 in benefits. It was supposed to be enough for the veterans for their first expenses. Roman Dmowski, in a letter to Jan Smulski dated October 12, 1920 and published in the "Dziennik Związek", thanked for the contribution of the Polish community in the work of regaining Independence. Apart from having received some appreciation and being honored with the Cross of Volunteers from America, the veterans were left to themselves. Many of them were disabled or lost some of their health. They started to organize help for their needy friends. In May 1921, they established SWAP - the Association of Polish Army Veterans in America. Its first president was Colonel Dr. Teofil Starzyński, president of the Polish Falcon in America. The tireless organizer of the recruitment campaign, faithful to the falcon's oath, went with his friends to the front as a doctor. The list of people like him goes on. The SWAP was supported with $10,000 in 1926 by the greatest of Falcons, I.J. Paderewski. It is thanks to individuals like THEM that the powerful Blue Army came into being.

In October 1919, General Haller was entrusted with the command of the Pomeranian Front, created for the peaceful and planned occupation of Pomerania, granted to Poland under the provisions of the Versailles Treaty. According to the plan, the takeover of the Pomeranian lands began on January 18, 1920. On February 10, 1920, General Haller, together with the Minister of Internal Affairs, Stanisław Wojciechowski, and the new administration of the Pomeranian Voivodeship, arrived in Puck, where he performed a symbolic wedding between Poland and the Baltic Sea. It was a beautiful, if only symbolic, gesture. In the summer of 1920, a new threat emerged from the east. General Haller received the function of the Inspector General of the Volunteer Army, in organizing which he contributed greatly. From a strategic point of view, it is difficult to understand why a well-equipped army was disbanded, in order to replace it with an army of volunteers. General Haller was slowly removed from military affairs, and after the May coup he completely withdrew from public life.

Piłsudski and Haller

The Blue Army and the political game around it are completely ignored in Polish historiography. The fact is that Haller's Army was the best trained and best armed tactical unit of the Polish troops and represented very high morale and combat capabilities. As a whole, under the command of General Haller, it could pose a serious threat to the emerging legend of Marshal Piłsudski. In 1919, he began to systematically replace the command cadre of the "blue" with his legionary. The demobilization of volunteers from the United States, the best part of this army, in the face of the threat of Soviet troops was amazing. It was not surprising, however, that when in June 1920, in the face of the Bolshevik threat, a volunteer army began to be organized, demobilized Haller Jews were massively flowing into it.

Does Poland love the Polish diaspora?

History repeats itself. In March 1941, a Polish recruiting mission arrived in Canada, bordering once again neutral, the still hospitable Canada. The recruitment mission of the Polish Armed Forces in the USA and Canada took place in 1941-42 and was commissioned by General Władysław Sikorski, after his visit to America, where he was enthusiastically welcomed by the Polish community and, on this basis, assumed that the recruitment would result in an influx of volunteers to the PES in Great Britain. The mission turned out to be a failure. The Polish community has drawn conclusions from the experience of the Blue Army. Despite everything, bitterness and pain, a sense of moral harm, the Polish community abroad has always supported and supports a free and sovereign Poland. An example of this can be the activities of the Polish community during the martial law, efforts to enter Poland into NATO and activities aimed at the deployment of American troops in Central and Eastern Europe. Nine million signatures on a petition supporting Poland's request to join NATO were of importance. The marginalization of the participation of the Polish diaspora in political and social life is not good for Poland.

We have analyzed many historical studies and articles that mention the Blue Army. Most of them remain silent about the subsequent fate of American volunteers. They don't fully or objectively evaluate the role of the Polish emigration (Polonia) in the creation of the Independent [Polish state]. There are no witnesses to this history anymore, but substantial American archives remain, which allow to extract the truth about the great patriotism of over 20,000 soldiers and the entire army of involved civilians, Polish community activists who, together with volunteers, dedicated themselves to creating a great and strong, free and independent Poland and for whom we should also ensure a worthy place in our historical memory. In the celebrations of [the Polish] Independence Day in the USA, at Polish diplomatic missions, the most important thing is the portrait of the Marshal [Piłsudski] and the thundering silence about the volunteers "who left the Niagara-on-the-Lake camp to fight for a free Poland".

Photos courtesy of the Association of Polish Army Veterans in America.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz, with the help of Google Translate.