Poland’s rebirth as an independent nation in 1918 is one of the most remarkable events of modern history.

Poland’s internal weaknesses and corruption combined with powerful autocratic neighbors had sealed the country’s fate by the end of the eighteenth century. The partitioning powers of Prussia, Austria, and Russia had turned Poland into a colonial possession and made a coordinated effort to suppress any hint of political autonomy for their Polish subjects. The First World War resulted in the collapse of the three partitioning powers, but the real credit for the rebirth of Poland goes to the Poles themselves who after 123 of struggle stepped into the vacuum left behind and defended their re-established state against a major Bolshevik invasion.

One of the forgotten elements of Polish independence is the role played by Polish Americans in Poland’s restoration. Polonia’s contribution was overlooked due to the passage of time, interwar political divisions, and the impact of World War II and the subsequent communist takeover.

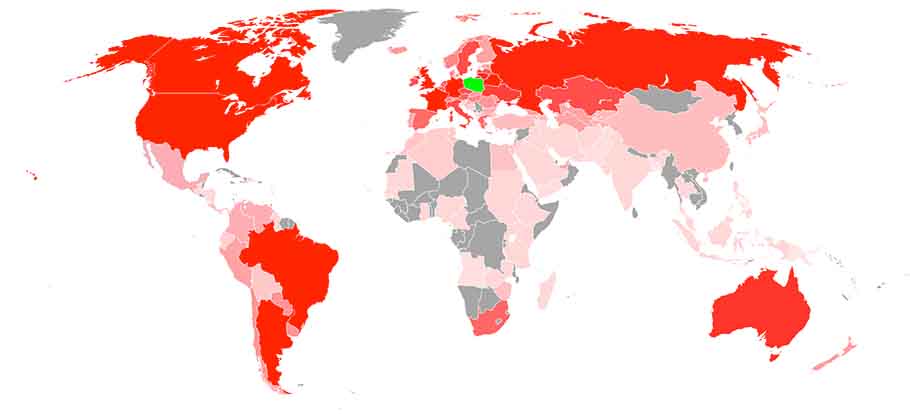

By 1914, American Polonia was over 2 million strong. These were Poles who had immigrated to the USA since the 1850s and their American born children. They lived mainly in the Great Lakes and Midwestern states as well as on the eastern seaboard of the United States. Most were urban factory workers or miners, though about 10 percent were farmers. Although they were poor by American standards and suffered discrimination at the hands of many Americans, they had made significant economic and cultural progress, creating hundreds of churches, schools, libraries, newspapers, hospitals, and other organizations. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s Kulturkampf—aimed at repressing Catholics and Poles in Germany—as well as the 1905 Revolution in Russia and 1906–07 school strike in Prussia had energized Poles in America on behalf of the Polish cause. American Polonia was referred to by many as the “Fourth Partition.”

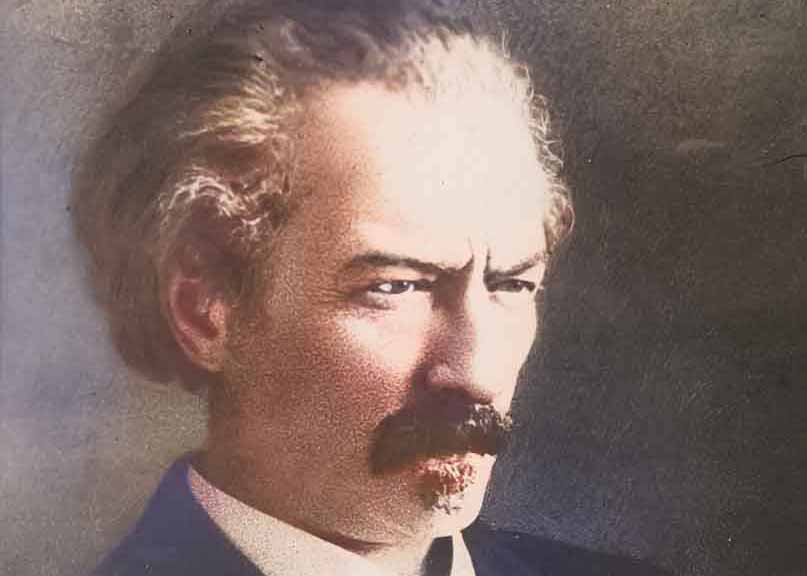

By 1907, Polish American organizations were sending delegations to international peace conference as well as to international women’s conferences, in order to raise awareness of Poland’s plight. They had also begun to raise money for Polish causes. When war began in Europe, Poles in America had developed two umbrella organizations, the socialist-oriented Komitet Obrony Narodowej (KON or National Defense Committee), and the much larger Catholic-led Polska Rada Narodowa (PRN or Polish National Council), which supported the work of Paderewski. In October 1914, PRN joined formed the Chicago-based Polish National Relief Committee. Yet, even before the war started, Polish Americans were providing substantial help for Poland. In the spring of 1914, a series of devastating floods had struck Galicia and the Polish Roman Catholic Union (Zjednoczenie Polskie Rzymsko-Katolickie w Ameryce) had quickly raised $12,000 to help the victims of the disaster. For such a poor community, this was a major achievement, but it would soon be overshadowed.

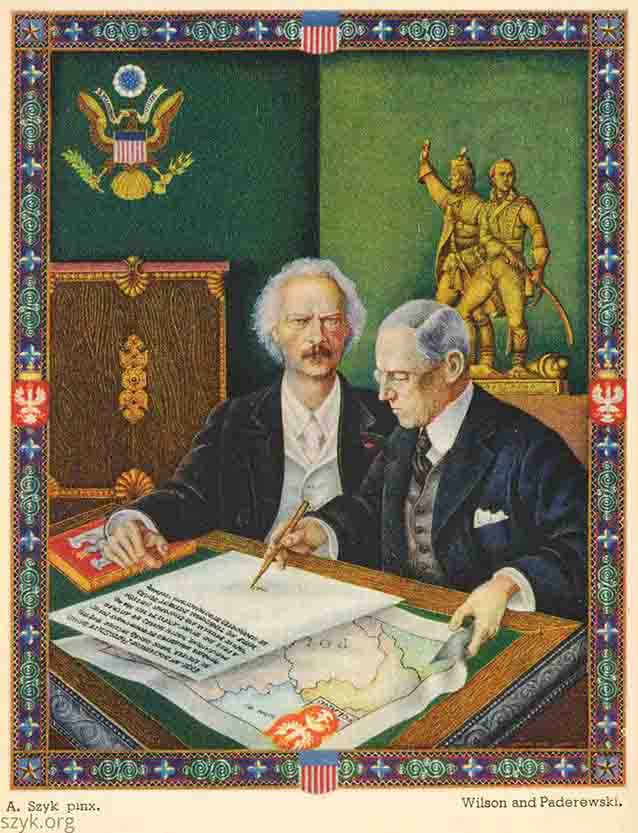

Paderewski and President Wilson (Source: Wikipedia)

From the start of the war until 1922, Polish Americans raised an about $50 million for Poland (or about $600 million or zl. 2 billion in 2019 currency). This included $5 million for the National Fund, $1.5 million for the Polish Army, and $3 million in clothing and food aid. Polish Americans bought large amount of Polish government bonds. In addition, they provided an estimated $30 million dollars in direct assistance to family members in Poland.

As the war came to an end and Poland struggled to knit itself together and stand up to foreign invasion, Polish communities in America were called on to help once again. Poles were urged now to buy Polish government bonds and to contribute for food, clothes, and medicine to prevent deaths from hunger and disease. Other contributions were taken up to support the Polish armed forces as they struggled against a massive Bolshevik invasion in 1920. Polish parishes, organizations and families all over the United States from small farming colonies in Minnesota and Texas of a few hundred families to large urban centers like Chicago or New York, donated and raised money. Parishes held special benefits and fundraisers while school children collected nickels and pennies. For many parishes, their contributions to the Polish cause remained a source of pride for many years. St. Adalbert parish in East Saint Louis collected $19,590.95 for Polish relief in the years 1917 to 1921. [1] In a day’s single collection recorded in October 1918, the parish of St. Stephen in Chicago donated $137.12, the Poles of Holy Cross Church in Minnesota gave $2,544.44, while the parishioners of St. John Cantius in Chicago gave $1,434.95 in cash, $2,700 in Liberty Bonds, $100 in checks, and $127.46 in postage stamps (for a total of $4,362.41). [2] In many cases, students at Polish parochial schools collected pennies and nickels. The $50 million given by American Polonia was in addition to purchasing $99 in U.S. government bonds. What is especially noteworthy here is that these large sums came not from America’s wealthy elites but were given by people who had very few resources and who themselves had often struggled to provide good clothes, food, and shelter for their own families.

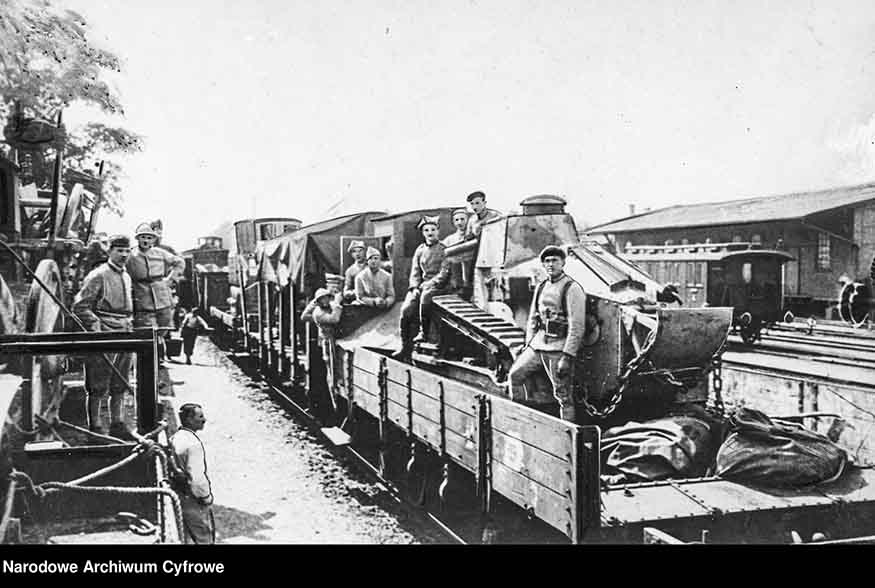

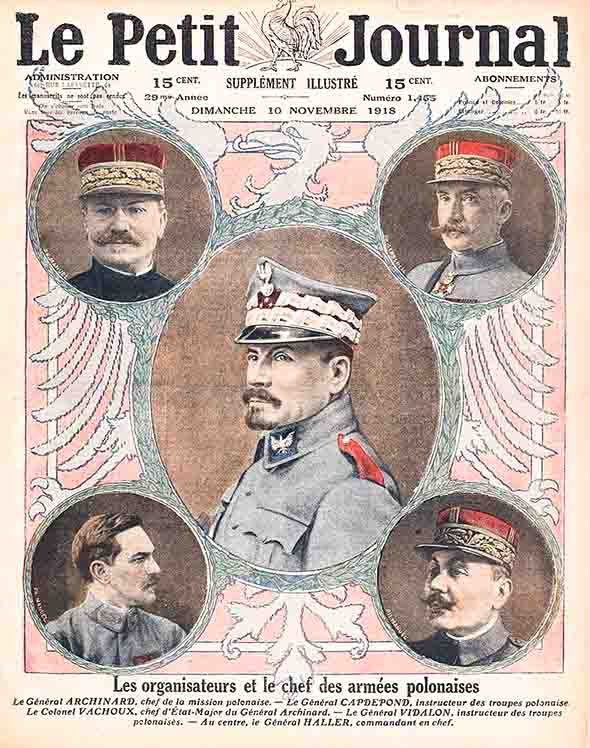

About 38,000 Polish Americans volunteered for the Polish Armed Forces between 1916 and 1920. Of these, about 24,000 served in the Polish Army from 1918 to 1921. The so-called “Blue Army” (Błękitna Armia) saw action in the conflict between Poland and Ukraine and more importantly in the Polish-Bolshevik War where American Poles served with distinction in the battles for Polish independence, particularly in the Battle of Radzymyn battles and against the 1st Red Cavalry Army. These soldiers were recruited across the U.S. at special Polish recruiting centers and then trained in Canada before being sent to France where they were equipped and served with the French Army under Polish colors until 1918 when they were sent to Poland.

Recruiting poster by W.T. Benda (Source: Wikipedia)

Men from American Polonia were not the only ones to fight for a free Poland. The best known example is the American pilots who helped form the Kościuszko Squadron. Led by adventurer and later film director Merian Cooper, the squadron’s exploits in the Polish-Bolshevik War are legendary. So feared were the Kościuszko fliers that the Soviets put a bounty of half a million rubles on Cooper’s head. Despite being shot down and captured, Cooper managed to escape communist captivity and return to Poland, becoming one of two Americans to be awarded the Virtuti Militari during the war.

Many young Polish American women volunteered to serve as nurses and aid workers in Poland. Two groups, the Polish White Cross, formed by Helena Paderewska, in order to support the Polish Army in France (prior to the formation of a separate Polish branch of the Red Cross) and the Grey Samaritans, were made up almost entirely of American Poles. Because they all spoke Polish, the Grey Samaritans were often the ones who distributed the food and medical aid from the USA. They ran soup kitchens throughout Warsaw and in several other cities, including Kalisz, Łódź, Pińsk, Lublin, Wilno, Kielce, and Lwów. They also organized groups of Polish women into sewing circles to make clothing for the destitute. It was the “Greys” who made sure that donated food and clothes went to those in need and wouldn’t be pilfered by corrupt officials or common thieves. One young woman wrote that people “in Kielce call us ‘American guards’ because we are always watching.” American relief officials later attributed much of the success of the relief effort in Poland to the work of this long-overlooked organization. One American official reported: “The Polish Greys have increased the efficiency of the clothing program by 50 percent … 50 percent more children have received outfits than otherwise if the girls had not been supervising.” Herbert Hoover himself paid tribute to these women: “I would like to express the gratitude we all owe and the appreciation we all feel for the extraordinary services of the Polish Grey Samaritans. The hardships they have undergone, the courage and resources they have shown in sheer human service is a beautiful tribute to American womanhood.” [3][4] As the American relief program came to an end, many of the Greys turned their attention to training groups of Polish women to serve as social workers for the new Poland.

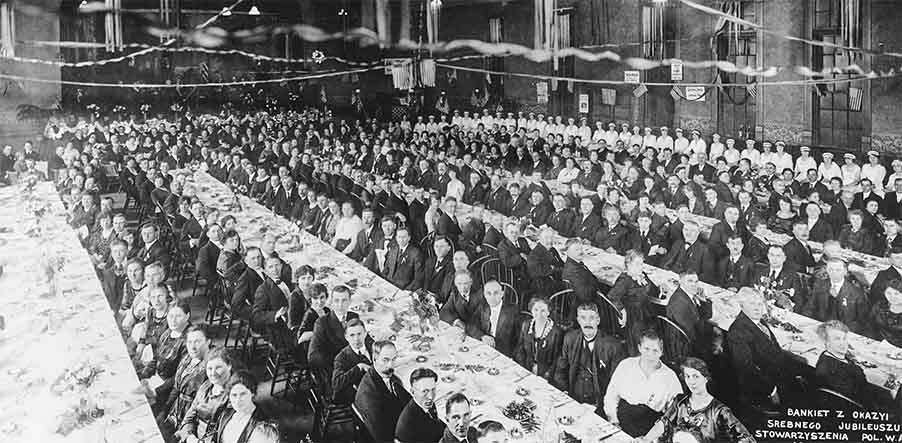

Banquet on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Association of Poles in America, Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Source: Roman B. Kwasniewski Photographs Collection Archives, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.)

In the years after the Polish-Bolshevik war, however, the ardor for Polonia’s help cooled. Many Poles came to view Polish Americans as interlopers and as interfering foreigners rather than brothers and sisters. The fact that American Polonia largely supported the National Democrats more than Pilsudski’s Socialists didn’t help win favor with the Polish government. Many Polish Americans found the new Poland dirty and corrupt and far from the ideal nation they had envisioned emerging after the Partitions. Their encounter with Poland brought many to realize that they had been transformed by their sojourn in America and while most Americans viewed them as Poles, in Poland they were seen as Americans.

American Polonia would retain a deep and abiding attachment to Poland, but their experiences in the struggle for Polish independence led most to realize they were American as well as Polish. For Poles, the problems of creating a new nation from three separate Partitions and overcoming the poverty and destruction caused by the war led most to forget the important role played by their American cousins in securing Poland’s freedom.

A century has passed since the momentous events of 1918 to 1921 and Poland’s return to map of Europe. For both Poles and Polish Americans, it is long past time to recall the common effort for Polish independence when our ancestors changed the course of history.