Paderewski is the pride of Poland. He is one of the three most important Polish activists and politicians who worked on and won Poland's independence in 1918. These three greats are Ignacy Paderewski, Roman Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski.

Paderewski was deliberately forgotten by the ruling camp in the interwar period, and after the war, actively suppressed by the communists. Also today, there is a lot of incorrect or incomplete information about him on the Internet. To this day, there is no complete, objective monograph about him.

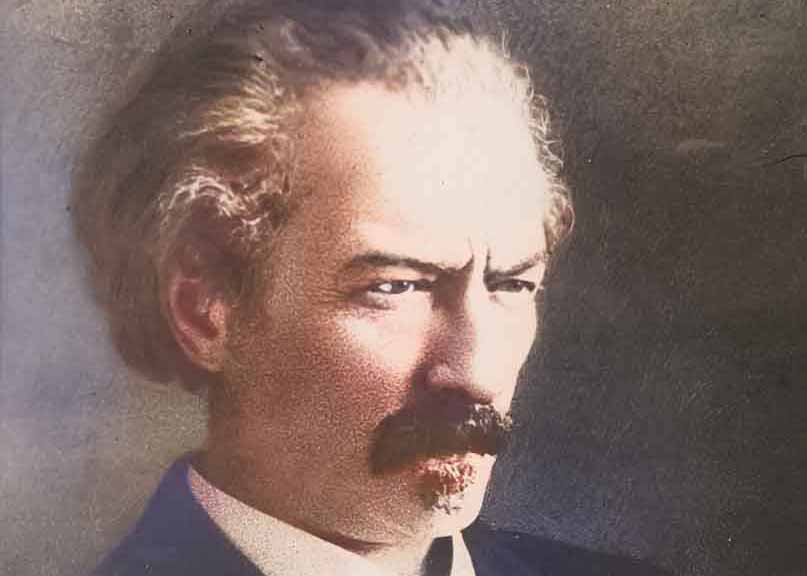

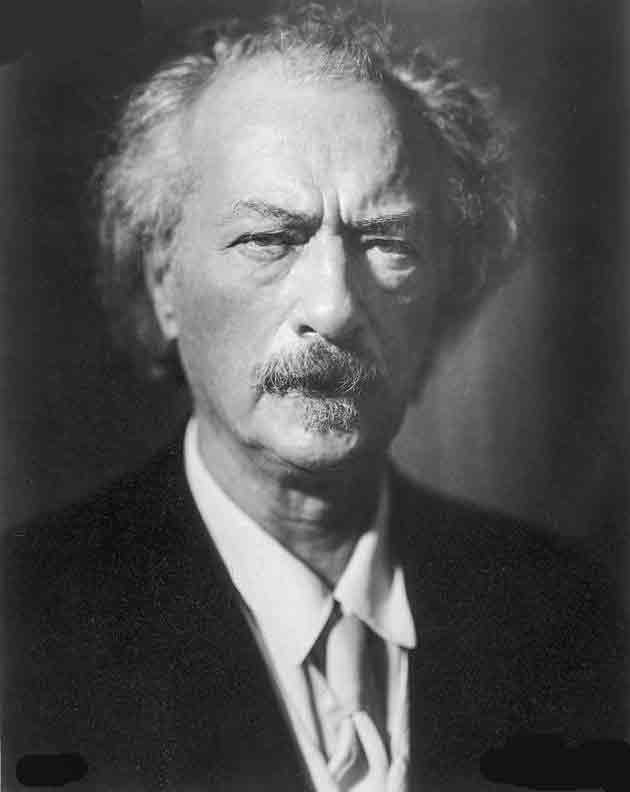

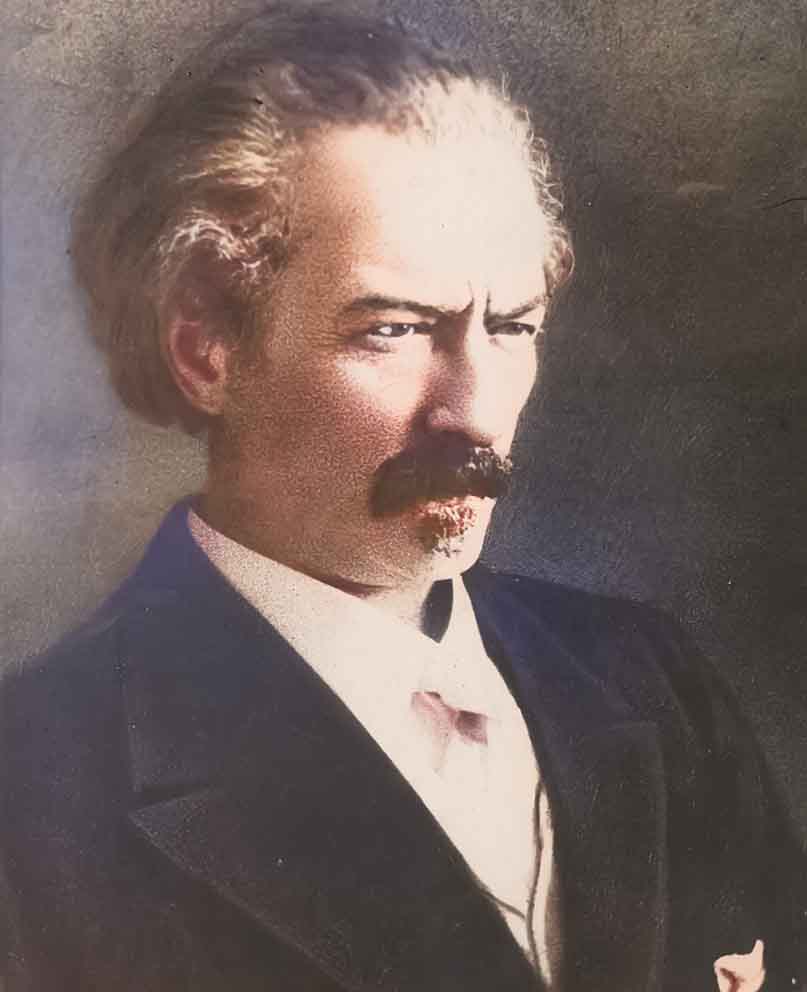

Ignacy Jan Paderewski in the 1920s. (Source: National Digital Archives. Color: A. Woźniewicz)

Ignacy Jan Paderewski was a unique and extraordinary personality. He had a profound and special influence on the history of Poland, the history of Polish Americans, the history of music and the history of culture on a global scale. He was a pianist, composer, statesman and philanthropist. Above all, he was a noble, generous, hard-working, good man. His contemporaries called him "immortal", and as an artist he was undoubtedly a genius.

Who was Paderewski really? Who is he for us today? How can he help us live better? What was his vision of Poland? And what do we owe him? In trying to answer these questions, we must first recall the most important facts about his life and work.

The life of Ignacy Paderewski (1861-1941) is clearly divided into four periods.

- The first (1861-1888) covers twenty-eight years of study, preparation, first public piano performances, and first compositions.

- The second (1888-1915) spans over a quarter of a century of dazzling, world-class piano career, as well as intense compositional creativity.

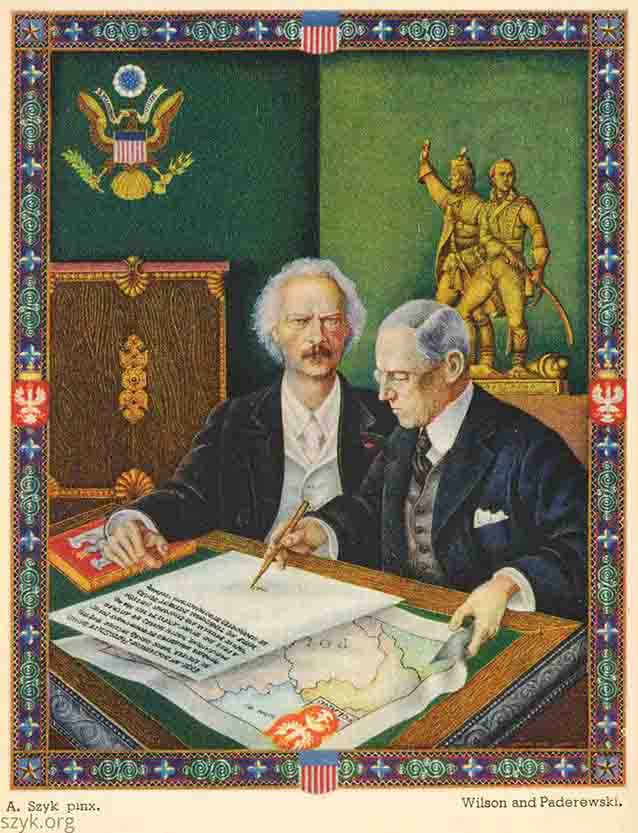

- The third (1915-1921) was six years of active politics. Taking over the leadership of the Polish American community and advising US President Wilson; Presidency of the Council of Ministers in Poland; struggles at the Peace Conference in Versailles and acting as Poland's representative in international bodies.

- The fourth (1922-1939), lasting seventeen years: the time of reigning on the stages of the world, and at the same time holding the position of the highest national authority. Then there was only a short epilogue to this long and beautiful life, the last two years (1939-1941) again devoted entirely to public service.

In the first period, Ignacy Paderewski grew up in a modest gentry, landowning manor in Podolia and Volhynia. He didn't know his mother. She orphaned him when he was a few months old. At home, he received basic general education and the basics of playing the piano, as well as patriotic formation: his father was imprisoned by the Russians for a year for his participation in the 1863 Uprising. Young Paderewski grew up in the atmosphere of the memory of great independent Poland, he listened to stories about heroic victories and tragic uprisings felt the burden of Poland enslaved by three invaders - Russia, Germany and Austria.

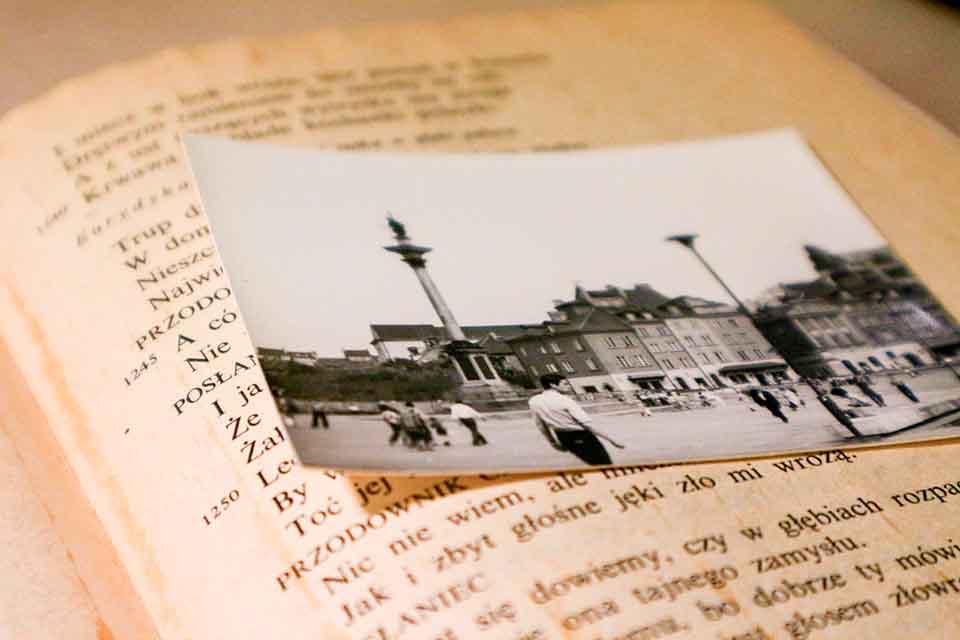

At the age of 12, he began to study music in Warsaw. The professors did not consider him particularly gifted, and one of them even advised him against continuing to play the piano. At the age of eighteen, however, he graduated with very good grades from the Warsaw Conservatory (1878) and immediately afterwards took up the duties of a piano teacher there in lower classes. At the same time, he also composed, and — soon — very mature, works at that.

At that time he married, but his wife died soon after the marriage and gave birth to a son, Alfed, a child of very poor health, who died young.

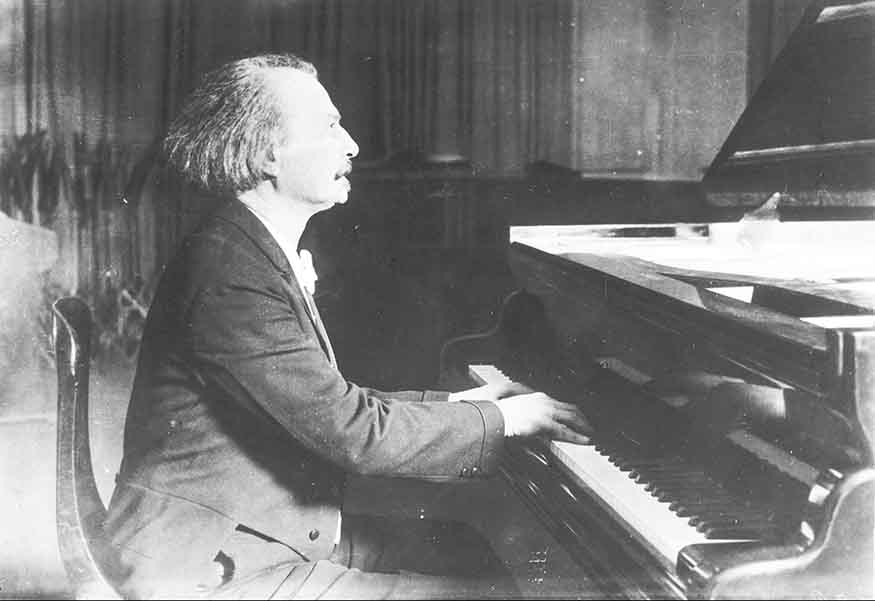

Photo of Paderewski from 1895-1915, taken in the studio of Jadwiga Golcz in Warsaw (Source: National Digital Archives)

The career of the young musician was accelerated by the excellent actress Helena Modrzejewska, to whom he was introduced during one of her returns from America for guest performances in the country. Modrzejewska recognized Paderewski's enormous talent, organized a concert for him in Kraków (1884) and drew the audience to it, initially personally reciting by herself. The proceeds obtained, and her own grant, enabled Paderewski to study in Vienna (1885) with the famous pedagogue Teodor Leszetycki, extended by a series of lessons two years later. At the same time, Paderewski constantly and tirelessly worked on himself.

Concerts in Paris (1888), ended with a wild success, opened the way to fame for him. Soon he gave concerts in Belgium, London, Berlin, and finally in the United States (his first tour, 1891), gaining more and more success, winning over critics and focusing the audience's admiration on him. His phenomenal piano technique was the unwavering foundation of personal and innovative interpretations, crowned with inspired, ecstatic, thrilling playing. At the same time, he was a beautiful, well-built man, and his golden, lion's hair gave him an unusual appearance and an aura of beauty.

Situational photograph of I. Paderewski from 1925 (Source: National Digital Archives)

Since the conquest of the capitals of Europe and the great cities of America, Paderewski has become a world-famous virtuoso, the object of a cult called "padymania." He aroused both respect and interest as a composer. He often played his own songs at concerts, especially as an encore. Perhaps most often he played the encore of his Minuet à l'Antique, Opus 14, Number 1 (a work composed in 1884).

Preparing for concerts, Paderewski practiced day and night, constantly imposing on himself the absolute rigor of work, often spending 17 hours a day at the piano, leaving four hours for sleep and three for meals. Hard work has always been the basis of his success. Over the course of a quarter of a century, he was constantly at the peak of fame as a virtuoso, as well as as a social and financial success. He played at royal courts and presidential residences, he was decorated with orders and bestowed upon with honorary doctorates. He has traveled all over the world giving ten grand tours of the United States, going to South America, Australia and New Zealand. He purchased an estate in Kąśna near Tarnów, two ranches in California near Paso Robles, and a mansion in Riond-Bosson in Switzerland.

Villa owned by Ignacy Paderewski, Riond-Bosson, Switzerland. (Source: National Museum, Warsaw)

He was always extremely generous, donating large sums of money to charity, scholarships, foundations, and charity events. This chord of his activity resonated loudly when he funded the Grunwald Monument in Krakow, for the 500th anniversary of the victorious battle with the Teutonic Knights (1910). It was a great national act, which for the first time showed Poland, as well as its anxious partitioners, Paderewski — a virtuoso and composer — as a fiery orator, an indomitable patriot, a leader capable of captivating the hearts and imagination of the masses.

By funding the Grunwald Monument in Krakow, gathering crowds at its unveiling and speaking to them, Paderewski recalled the great past of the nation and focused its hopes for a better future, for independence. He repeated his message in a speech at the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Chopin's birth in Lviv (1910). He felt more and more keenly the suffering of Poles in the country and established closer and closer contacts with the American Polonia. Poles around the world were proud of him and gradually pushed him to a leadership position.

In the following years, Paderewski resumed his tense regime of frequent concerts, which required constant travelling.

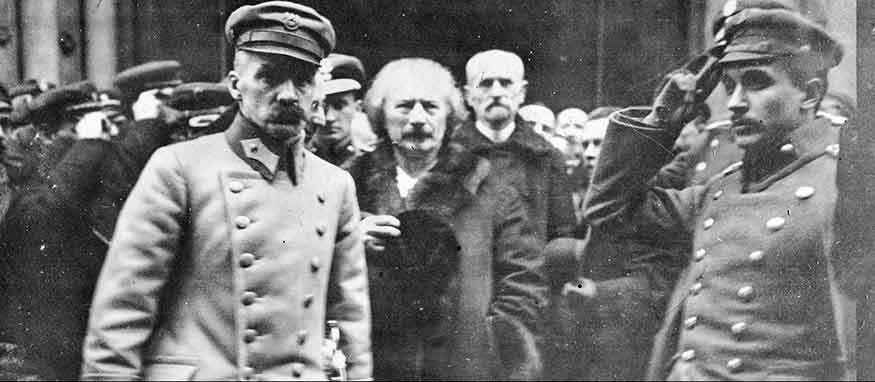

Head of State Józef Piłsudski (first from the left), Prime Minister Ignacy Paderewski (second from the left), Minister of Internal Affairs Stanisław Wojciechowski (third from the left) and the Head of State's adjutant, lieutenant Tadeusz Kasprzycki (first from the right) after a solemn service in the Cathedral of St. John, February 9, 1919 (Source: National Digital Archives)

During World War I, Paderewski, first in Switzerland and then in the USA, undertook an enormous and energetic charitable and political work on several fronts at once. At that time, he also conducted intensive, very detailed, self-taught studies of the history and geography of Poland, which prepared him for the great task he undertook - to regain independence by Poland.

In particular:

He helped Poles materially: he created the Polish Rescue Committee, collecting money for it and directing his earnings to it himself. In this way, he helped Poles in a country devastated by moving fronts.

He undertook political activities aimed at resurrecting an independent Polish state: he joined the Polish National Committee (KNP) established in Paris by Roman Dmowski as its member and delegate to the United States. The KNP was the nucleus of the Polish government abroad and was later recognized as such by the Allies (1917).

He undertook the work of uniting all Polish organizations in the United States, which he almost fully succeeded in, and thanks to this, Polonia spoke with one voice on matters of their home country. Paderewski himself became the informal leader of the entire American Polonia.

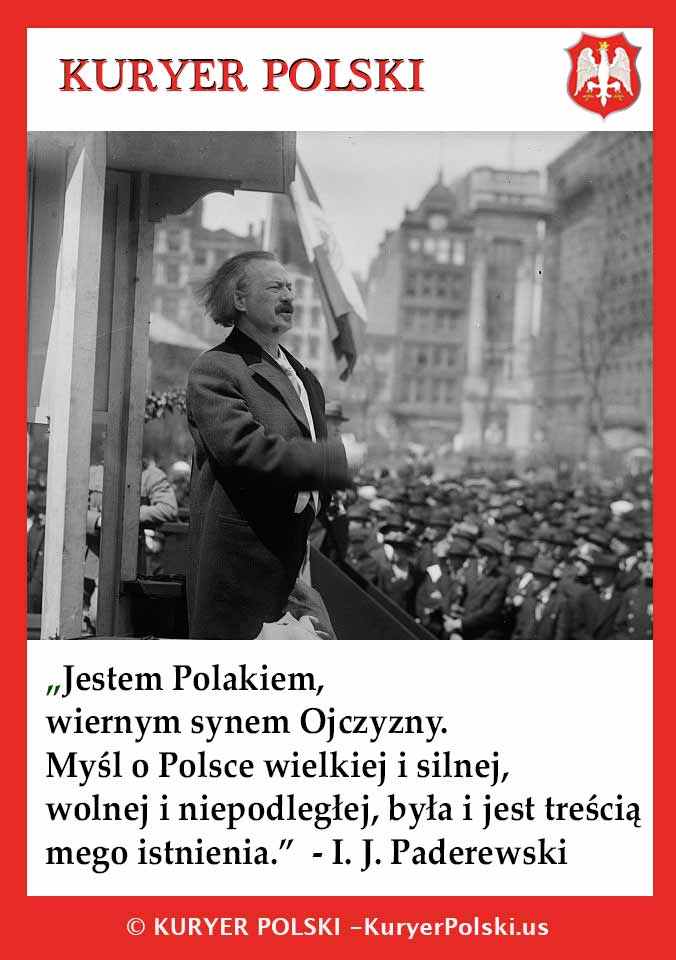

He developed a broad propaganda campaign for Poland in the United States, on two levels simultaneously. On the one hand, he appealed to the American public opinion and mobilized it for Poland. He devised an unusual mode of operation, available only to himself: a piano concert combined with a political gathering. First, he played the piano, attracting thousands with his name of a world-famous virtuoso, and then he would get up from the piano and give a speech about the need to resurrect independent Poland. He gave three hundred such concert-meetings. On the other hand, he established cooperation with the American government and President Wilson, whom he met personally. At the request of the President, Paderewski prepared a memo on Polish matters, explaining the reasons for which Poland must regain independence, and showed its fair borders, with access to the Baltic Sea. Thanks to Paderewski, based on his memo, President Wilson included in his peace program the famous point 13, which stipulated, as a condition for post-war peace, a united, independent Poland, within fair borders, with access to the sea (January 1918). It was this Paderewski memo, and Wilson's postulate based on it, that introduced the Polish cause into the orbit of war and post-war goals of the states of the coalition fighting against Germany - the USA, Great Britain, France, and then Italy. These countries described Poland's regaining independence as one of the important elements of the post-war world order.

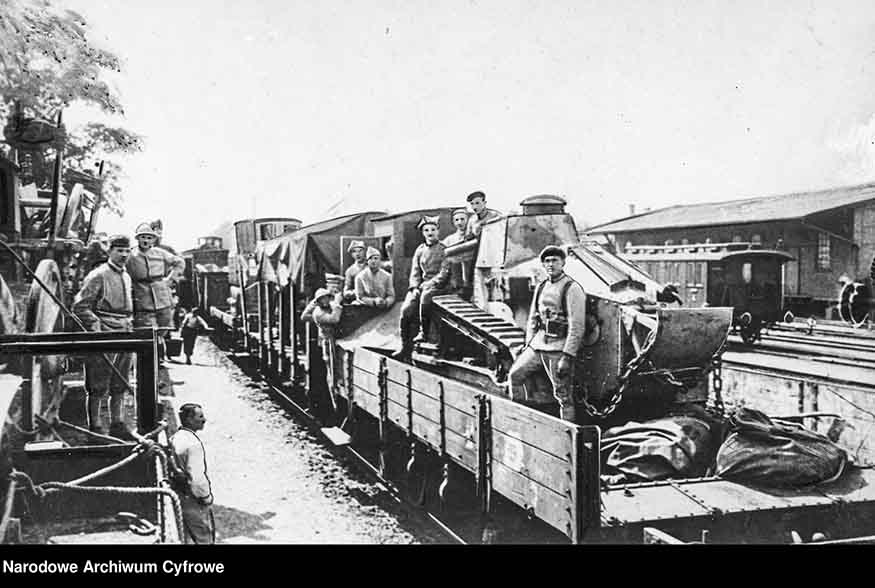

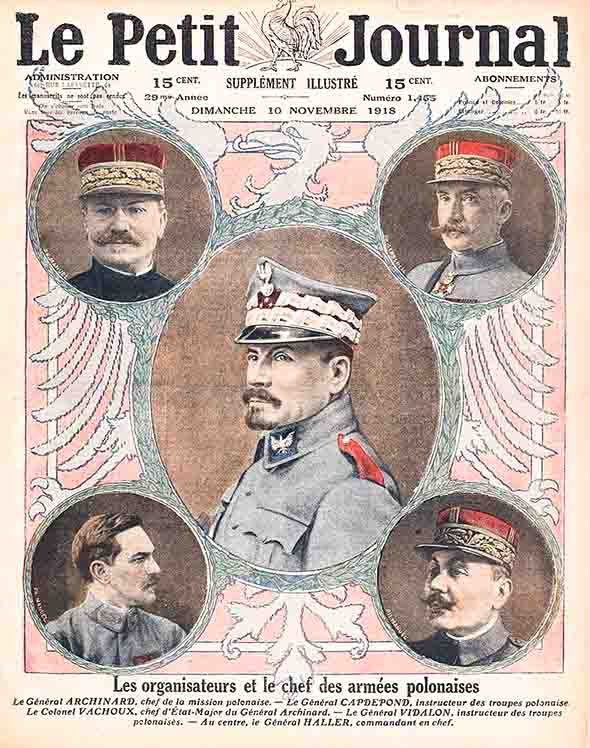

In the spring of 1916, Paderewski put forward a project (based on earlier Polish efforts made in France) to create a Polish Army fighting alongside the United States. After various delays, such an army began to form in the autumn of 1916, and was formally created on October 6, 1917. It reached a strength of over 22,000 soldiers. They were all volunteers from Polish immigrant families. It was Paderewski's army. The blue uniforms and weapons were provided by France. Hence the army was called the "Blue Army". The training took place on the territory of Canada, the dominion of Great Britain fighting against Germany. (The US did not formally participate in the war until April 6, 1917). In May 1918, this army was transferred to France and immediately entered the fight. Its political leadership was provided by Dmowski's Parisian Polish National Committee, which appointed General Józef Haller as its leader on October 4, 1918. From that date, the "Blue Army" was also called "Haller's Army" or "Hallerczyks". This army absorbed Poles - Allied prisoners and deserters from the invaders' armies, grew to about 80,000, and ensured Poland's participation in the Allied victory parade in November 1918 in Paris. Then, in a decisive way, it was to strengthen the army of the reborn homeland.

All these works and their visible fruits naturally assigned Paderewski to the next, highest task: to take the leadership of all Poles, beyond partition borders and party differences, to unite all the best Polish forces in the country and around the world. Paderewski decided to return to Warsaw, which was facilitated by the Allies.

After reaching Gdańsk on December 25, 1918, on an English warship, Paderewski arrived the very next day, December 26, in Poznań, where his very appearance sparked an uprising and, consequently, the return of a huge part of the Prussian partition to the Motherland.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski among those welcoming him on December 27, 1918 in Poznań. (Source: National Digital Archives)

On January 1, 1919, Paderewski stood in Warsaw. He was welcomed as a savior. Perhaps even more enthusiastically than Piłsudski returning from a German prison six weeks earlier, because Paderewski, apart from the legend of a world-famous artist, a passionate patriot and a generous philanthropist, announced the bringing to his homeland of a select army - concentrated in France for the time being - and sending Western money to Poland, as well as economic aid, to provide the country with broad borders and peace within them. He had a triple mandate behind him: the will of the majority of Poles in the country and abroad, the authorization of the Parisian Polish National Committee, and the support of the victorious Allies.

In Warsaw, Józef Piłsudski was already in charge, brought to power by the will and hope of the people. He held the office of the Chief of State (so named after Kościuszko's example) and patronized the socialist government of Jędrzej Moraczewski. Piłsudski initially did not want to share power with Paderewski. Soon, however, he realistically assessed the personal values and political dowry offered by Paderewski. He appointed him the President of the Council of Ministers and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, which happened on January 16, 1919.

As head of the government, Paderewski undertook a gigantic task of organizing the law, administration, economy, and above all, unifying the lands and population of the three former partitions.

Then he participated in the Peace Conference in Versailles, where Dmowski had been the Polish delegate until then. Paderewski recognized Dmowski's leadership position in the Parisian Polish National Committee and his enormous diplomatic contribution to the work of regaining and strengthening Poland's independence, and Dmowski wisely understood how great Paderewski's personal authority was and what capital he enjoyed among the Western Allies. So Dmowski loyally gave Paderewski the place of the First Delegate of Poland at the Peace Conference, becoming the Second Delegate himself.

Composer and pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski (third from the right) during a visit to the Prime Minister of France Raymond Poincare (first from the right), 1919 (Source: National Digital Archives)

There was something thrilling, unusual, symbolic and even mystical about the fact that the resurrected Poland was represented at the World Peace Conference by a great artist. Everyone knew that, as an artist, he stood at the top. But something else dominated the political struggle that was raging at the Conference all the time: his unique, powerful personality, in which iron will and delicate sensibility were inseparably intertwined; structured historical knowledge with the speaker's creative inspiration; the gift of establishing personal contact, being open to the interlocutor and looking for common ground with him, combined with the ability to keep one's own opinion. All this was based on fanatical diligence, refined culture and impeccable manners, and supported by knowledge of languages, history, geography and economic issues.

Both, towards the representatives of great powers and small nations, Paderewski maintained respect and communicated with them at the level of universal values, the general good, and common justice. He often collided with a different value system of the other side, with ruthlessness and political cynicism, with the interests of the stronger, imposed by force on the weaker. But he persevered.

At the Versailles Conference, Paderewski and Dmowski won for Poland what they could, undoubtedly more than anyone else could have done. For themselves, it was not enough, but they understood the conditions of the decisions made.

During the Peace Conference, Paderewski made efforts to transport his army to Poland. Despite the obstacles thrown at his feet by Germany and England, he led to the Blue Army, under the command of General Haller, being transferred to the now independent Poland and its soldiers becoming an essential force in the war with the Bolsheviks in 1920.

After returning to Warsaw in July 1919, Paderewski was accused of yielding to the Allies. He gradually lost the support of both Piłsudski and political parties. Wincenty Witos, a peasant leader who, shaped for years in the Austrian parliament, withdrew his trust, did not understand Paderewski's multi-partisan position and political style, or his program of uniting national forces above all divisions and particularisms. Dmowski remained loyal but was away in Paris. The Polish hell opened before Paderewski. On December 10, 1919, he resigned from his office.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski during his stay in Venice, 1925 (Source: National Digital Archives)

In February 1920 he left the country for Switzerland. He was never to return to Warsaw. However, when the Bolsheviks stood at the gates of the capital in 1920, Paderewski again declared his readiness to serve Poland. He accepted the position of Poland's delegate to the Council of Ambassadors and the League of Nations in Geneva. He fought for Poland as a diplomat. After Poland won the war, he was no longer needed by the rulers.

In early 1921, he left for America and settled in his ranch in Paso Robles, California. He made the decision to return to the piano. For half a year, he imposed on himself, as before, a backbreaking musical exercise program.

His first performance after many years at Carnegie Hall in New York (November 22, 1922) is described as one of the greatest events in the history of 20th-century music. Perhaps the greatest?

A well-known and respected statesman appeared on the stage. The hall honored him with a standing ovation. Then the great virtuoso gave a concert, playing with absolute perfection. Listeners, the world of music, fellow artists, critics, and impresarios were enchanted, delighted, carried away.

So Paderewski returned to the stages and for the next several years reigned there undisputedly, making subsequent tours. He spent his rest periods in Switzerland. He began to be called "immortal." Indeed, a book called Paderewski, The Story of a Modern Immortal by Charles Phillips was published in New York in 1933.

As early as 1920, a curtain of silence was drawn over Paderewski in Poland ─ yet not in America. He was treated by the government camp as a ─ still potential ─ competitor to power, and therefore he was kept away from the country. The gap deepened when, in the second half of the 1930s, after the death of Marshal Piłsudski, Paderewski patronized the efforts of General Władysław Sikorski, General Józef Haller, and Wincenty Witos (then not only deprived of influence, but also persecuted), who put forward a program of healing the Polish politics, creating together with Paderewski the so-called Morges Front (1936).

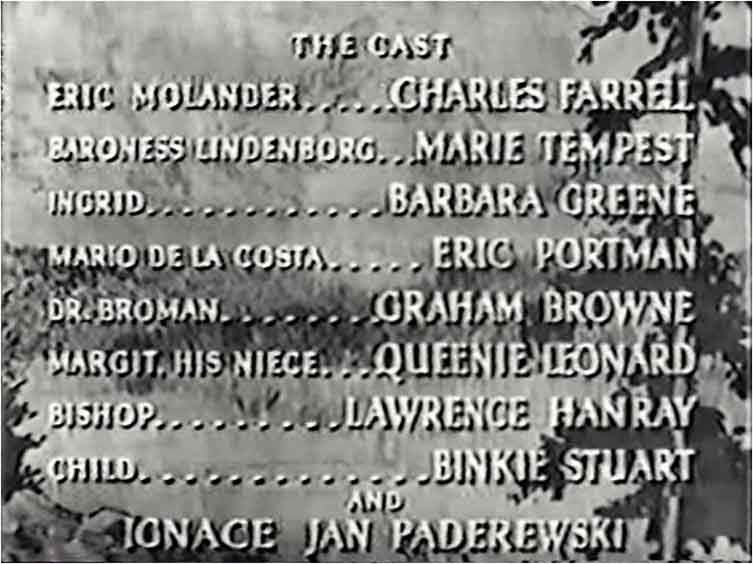

Still from the movie "Moonlight Sonata". (Source: YouTube)

He spent his life as a de facto statesman exiled from his country and still an active virtuoso. Only from time to time did news of his successes reach Poland. In 1937, Moonlight Sonata, an English film starring Paderewski, was shown in Poland. He willingly shared his skills and knowledge with younger musicians, inviting them for training stays at his Swiss residence in Riond-Bosson, he took care of the monumental edition of Chopin's works.

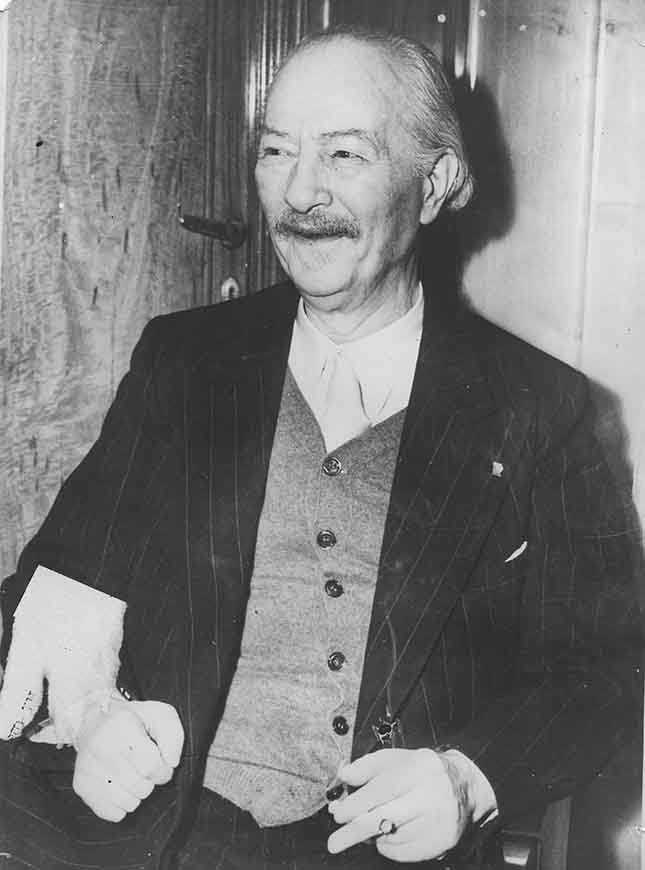

Ignacy Jan Paderewski in one of the film scenes in 1937 (Source: National Digital Archives)

The lost war with Germany and the Soviet aggression against Poland in 1939 again created the need to appeal to Paderewski's authority. Having already weakened his body, he did not accept the office of President of Poland that was offered to him. However, he did not shirk the chairmanship of the National Council of the Republic of Poland in Paris in 1940. Soon, as a national emissary, he went to the USA to mobilize the American, worldwide, and Polish diaspora opinion for the benefit of Poland. He died here in 1941, after a year of a murderous program of travels, talks, conferences, and speeches. Based on the personal decision of President Roosevelt, Paderewski was buried with the highest state honors that America can offer to a head of state at the Arlington Military Cemetery in Washington.

For the second time, the curtain of silence was drawn over Paderewski, or rather over his memory, by the post-war communist government. Paderewski wrote down on those pages of Polish history that the communists tore out of textbooks and tried to tear out of the hearts of Poles. Therefore, it was forbidden to talk about his extremely important role in resurrecting Poland. One could talk about Paderewski only as a musician – and then as little as possible.

The memory of Paderewski was inconvenient for the communists also because its main depositary was Sylwin Strakacz, then an emigrant. For over 30 years, he was Paderewski's personal secretary, serving him with absolute loyalty and total devotion, he accompanied him on trips, represented him in Poland, and cooperated politically abroad. Strakacz was a man of crystal character and impeccable reputation. During the war, he gained the respect and love of American Polonia serving as Consul General of the Republic of Poland in New York. After the war, he defended Paderewski's good name, his testament and the remains of his estate against the communist authorities, who expelled him from his office in America. The communists' attacks on Strakacz also disrespected the memory of Paderewski. Only for the American Polonia, Paderewski was a constant pride. His heart was solemnly transferred in 1986 to the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski after a concert in New York in 1939 (Source: National Digital Archives)

Only the changes of 1989 enabled Paderewski to return to Poland. In 1992, the ashes of the Great Pole were brought to Poland and solemnly placed in the crypt of the Warsaw cathedral. In 2001, the Sejm of the Republic of Poland passed a resolution on a special commemoration of the 60th anniversary of his death.

Paderewski's life was a source of comfort and hope for millions of Poles, a model of integrity and patriotism, as well as personal diligence and selfless public service.

Before the Polish Pope, John Paul II, Paderewski was the most famous and respected Pole in the world.

In Poland, for many years, Paderewski was the focus of the love of millions of Poles and the hatred of the political elite. He was a great statesman to many. For others, an ineffective politician. For music lovers and connoisseurs - he was a piano master and a great composer. However, over time, his memory faded away. Only the American Polonia always remembered him vividly.

In Poland – independent again – it is good to remind everyone about Paderewski who, a century ago, played a decisive role in restoring independence. We can always return to Paderewski with pride and gratitude – for strength and inspiration.

It is our noble national duty to honor Ignacy Paderewski.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.