On June 29 we celebrate the anniversary of the death of Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski was an outstanding pianist and composer, a passionate patriot and statesman, a philanthropist and social activist. His involvement in the Polish cause was absolutely selfless. He has permanently inscribed himself among the people who made the greatest contribution to Poland's regaining of independence.

He was born and spent his childhood in Kuryłówka in Podolia (the lands of the First Polish Republic seized by Russia in the Second Partition of Poland). There he received his first education (patriotic, musical, general), and his first public performances took place there. He continued his education in Warsaw, Berlin and Vienna. Soon he began his concert career, during which he had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of many personalities of the international political scene. He quickly became a widely known and respected person, and he built his fame also through charity work, an undoubted gift for oratory and his first political speeches concerning the current international situation.

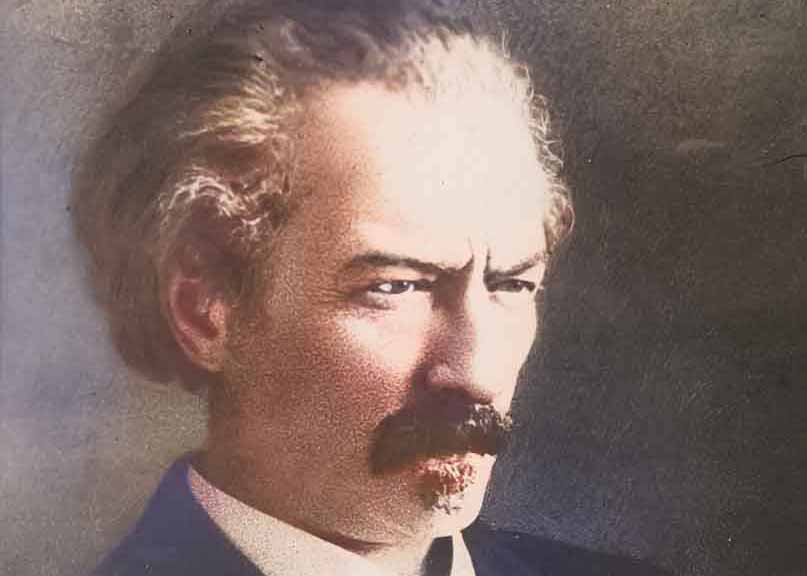

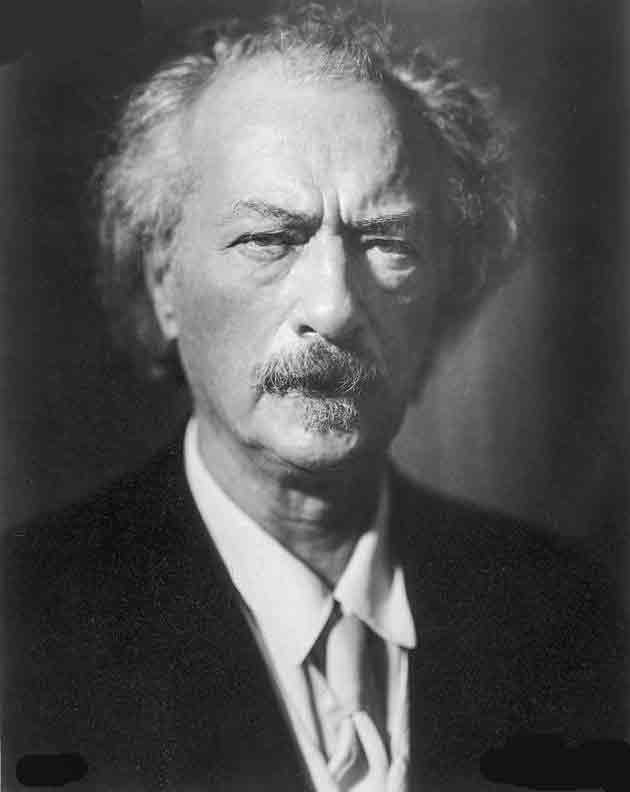

Polish pianist, composer and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) (Source: US Library of Congress/Wikipedia)

The unveiling of the Grunwald Monument in Kraków on 15 July 1910 was met with great resonance among Poles living in the three partitioning powers (Austria-Hungary, the German Empire and the Russian Empire) and those living in exile. It took place during the celebrations of the five hundredth anniversary of the memorable Battle of Grunwald (a.k.a. Battle of Tannenberg). The initiator of the construction and the founder of the monument was Paderewski, and it was a kind of prelude to his activities on behalf of the Polish cause, conducted during World War I and after its end.

Wartime Diplomacy

The outbreak of World War I found Paderewski in Switzerland, among the relatively small and politically diverse, but active Polish community there. Its representatives – influenced by news from Polish lands about the dramatic financial situation of their compatriots – in January 1915 established the General Committee for Aid to War Victims in Poland, with headquarters in Vevey. Paderewski became honorary vice-president and president of all branches of this organization that were to be established in other countries. The committee assured that in neutral Switzerland it would not undertake any political activities, which resulted in its official recognition by the Swiss authorities and enabled the launch of humanitarian aid for the civilian population of Polish lands.

Paderewski went to Paris and London in order to establish a branch of the committee there. In both cases, these missions were successful, but in order to attract representatives of the government circles of France and Great Britain to these bodies, he had to agree to the participation of official diplomatic representatives of Tsarist Russia, which was a wartime ally of Paris and London.

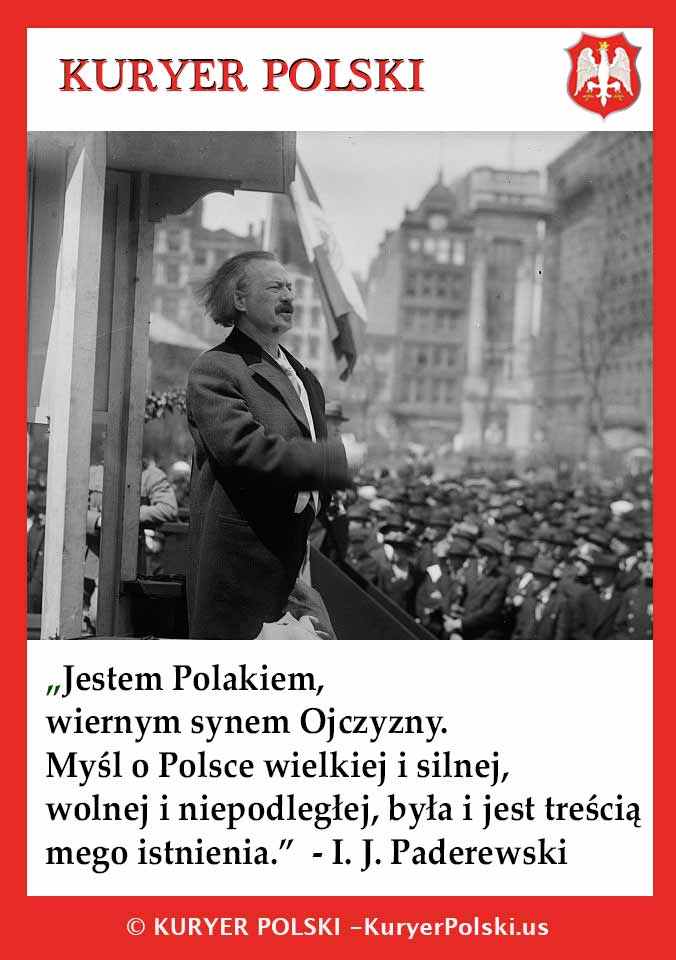

The next stage of Paderewski's journey was the United States (then also a neutral country), where many - at odds with each other - Polish organizations were operating. Wanting to activate the American Polish community and unite it around the idea of the Vevey committee, the pianist decided to tour all Polish communities in the USA. During this tour, he negotiated with representatives of the Polish emigration, gave concerts, and delivered fiery speeches. This activity was quickly noticed by the American society and the federal authorities, which is why many famous people sat on the board of the soon-to-be-established American Committee of the Polish Victims' Relief Fund.

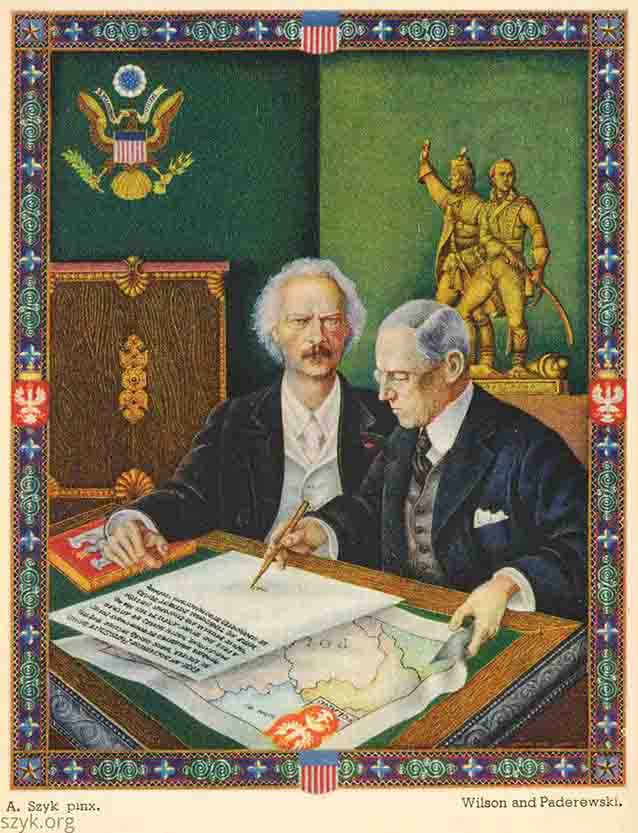

However, the most valuable thing was winning over Edward House, a friend and closest advisor to the then US President, Thomas Woodrow Wilson, to the Polish cause. Thanks to House's support, Paderewski was able to meet the American President twice in 1916. He spoke to him as an official representative of the Polish diaspora, having previously taken over the management of the National Department. This was a political organization, separated from the Polish Central Rescue Committee, which conducted charitable activities. The Committee united that part of the American Polish diaspora that sympathized with the Entente countries.

In early January 1917, House asked Paderewski to urgently prepare a memorandum on Polish issues to be presented to the president. Paderewski quickly prepared (based on various statistical and historical materials in his possession) two texts: one dated January 11, 1917, the other undated, written between January 11 and 22, 1917. In them, he described the history of Polish lands, the situation in the individual partitions, and a proposal for the future shape of a reborn Poland. And although there is no direct evidence of this, these memoranda may have influenced – even indirectly – parts of Wilson's two messages to the American Senate. The first message, dated January 22, 1917, contained the words "all politicians agree that there should be an independent, united Poland." The second, delivered on January 7, 1918, and commonly known as the fourteen-point peace program for the world after the end of World War I, contained (in point thirteen) the following sentence: "An independent Polish state should be created, which should include territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured free and secure access to the sea; its political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by an international pact." The second message in particular, delivered at a time when the United States was already engaged in the world war, strengthened support for the Polish cause in the arena of international politics.

Thanks to House's support, Paderewski was able to meet the American president twice in 1916. He spoke to him as the official representative of Polonia, having previously taken over the management of the National Department. It was a political organization, separated from the charitable Polish Central Rescue Committee.

Another area of Paderewski's activity was the efforts to create a Polish army in the United States - in the sense of independent military units, not auxiliary units of the armies of the Entente countries. However, these efforts were initially met with a decidedly unfavourable attitude of the American authorities, including President Wilson. It was not until the autumn of 1917 that it was agreed that volunteers from among American citizens of Polish origin, who were not covered by the conscription to the US army, would be recruited to the Polish Army being created in France.

Earlier, in August 1917, the Polish National Committee (Komitet Narodowy Polski, KNP) was established in Lausanne, Switzerland, with the ambition of representing all Polish affairs on the international stage (the KNP headquarters were soon moved to Paris). Roman Dmowski, the leader of the Polish national movement, became its president. Soon, the Entente countries recognized the committee as the official representation of Polish interests. The position of the committee's representative in the United States was offered to Paderewski, who at the same time continued the campaign to organize financial aid for Polish lands and encouraged people to apply for the Polish army. However, although the fundraising brought tangible results, the number of volunteers declaring their intention to join the Polish army was much smaller than expected.

At the head of the government

Paderewski ended his stay in the United States by establishing the Information Office (to promote the Polish question in the American press) and the Industrial and Commercial Office (to prepare the ground for future Polish-American economic relations) and in November 1918 he went to Europe. After a short stay in Great Britain and France he sailed aboard a British warship to Poland, whose independence was notified on November 16, 1918 and where a central government was already in operation, led by the socialist politician Jędrzej Moraczewski, while Józef Piłsudski acted as head of state – as the Provisional Chief of State.

Symbolic significance for the process of Poland's return to the Baltic Sea was Paderewski's visit to Gdańsk (December 25 and 26, 1918), where he accepted an invitation to Poznań from a group of independence activists from Greater Poland. He arrived in the city on the Warta River on December 26, greeted with applause by his compatriots. The pianist's stay in Poznań was the spark that led to the outbreak of the anti-German uprising. It quickly spread across almost the entire Greater Poland and turned out to be the only major Polish uprising to end in complete success: under the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, Greater Poland was annexed to the reborn Polish state.

From Poznań Paderewski set off for Warsaw, where he was also greeted with applause. Treated as the providential man of Poland, he was immediately drawn into the whirlwind of political events. Given the difficult internal and international situation of the country, it was necessary to change the previous government and appoint one headed by a person who enjoyed the support of a wide range of political parties in Poland, and at the same time - the trust of Western countries. Such a person was Paderewski. He was designated prime minister (officially called the president of ministers at that time) and held this position from 16 January to 9 December 1919, also heading the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Successes on the international stage, however, could not overshadow the difficult situation on the Polish political scene and the criticism of the actions of Paderewski's government. As a result, he resigned and also resigned from the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs. He soon went to Switzerland.

The most urgent issues of domestic policy, requiring immediate decisions, were: improving the difficult financial situation of the country (including combating inflation and ensuring liquidity in enforcing tax liabilities), rebuilding trade and industry, ensuring public order and security. In turn, in foreign policy, armed border conflicts with neighbours to the south and east (with Czechoslovakia, the West Ukrainian People's Republic and Soviet Russia) came to the forefront, as did the dispute with Germany – finally resolved peacefully. The provisions of the Versailles Peace Conference were key here. The Polish delegation to this conference was headed by Paderewski, as chairman (he arrived in Versailles on 5 April), and Dmowski, who had been replacing him until then. They also signed the document that went down in history as the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. Their authority, commitment, gift of persuasion, as well as the work of the other members of the Polish delegation, the Republic owed the most favourable decisions for it that could be achieved in the situation at that time. The Polish Parliament approved the treaty on 31 July 1919.

However, his successes on the international stage could not overshadow the difficult situation on the Polish political scene and the criticism of Paderewski's government. As a result, he resigned and also gave up his position as Minister of Foreign Affairs. He soon went to Switzerland. He briefly returned to active diplomatic service, accepting a nomination for the position of Poland's delegate to the League of Nations, an organization aimed at maintaining peace in the world. He held this position from July 18, 1920 to May 23, 1921 (he was given a warm ovation at the first ceremonial session of the League), after which he finally withdrew from active political activity. However, he closely followed the developments in his homeland. In 1936, he became a co-founder of the so-called Morges Front – an agreement of activists from opposition parties to the Piłsudski-led Sanation camp ruling Poland.

After the outbreak of World War II, he once again engaged his authority – both among his countrymen and on the international forum – in helping the Polish cause. He became the chairman of the National Council of the Republic of Poland, which served as the parliament in exile, but due to his advanced age and health, he only took part in one meeting of this body. In 1940, he went to the USA, where he continued – as best he could – his campaign for the Polish cause. He died in June 1941 in New York. He was buried with full honours at the Arlington National Cemetery. In 1992, his ashes were brought to Poland and placed in a sarcophagus in the Warsaw Cathedral of St. John the Baptist.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.