"Polonia Christiana" published (June 4, 2019) an interview by Tadeusz Kolanek with Dr. Teodor Gąsiorowski, entitled How the myth of Haller's Blue Army was killed. It is very good that we return to the figure of the great Pole and the great commander, General Józef Haller, and recall the Blue Army. It is a pity that, at the same time, the same text is part of the plot to kill the memory of, the destruction and concealment of the figure of another great Pole, Ignacy Paderewski. His name is never mentioned in this interview, which is a poignant "abandonment" — hard to believe, and impossible to justify. In this conversation, another great Pole, Roman Dmowski, the founder of the Polish National Committee, whose efforts with the French government were the decisive factor in the establishment of the Polish Army in France, was not even mentioned, even though the Army itself was described in the interview. I will focus here on the "Paderewski Case" - and on the truth about Paderewski, rather than on Paderewski's "myth".

Let us start by quoting Józef Haller's letter of October 15, 1918, to Ignacy Paderewski. Here is the full text:

Dear Master,

Having taken over the SUPREME COMMAND OF THE POLISH ARMY, I am in a hurry to express my appreciation and thanks to you and my soldiers for the enormous amount of work undertaken and completed - to the benefit of all of Poland - with such remarkable results. You are standing there, Master, in America, so friendly to us today - thanks to you - as a tireless soldier in an outpost of the Polish idea, and for this the Polish Army greets you with its cry "FOREHEAD". Having thousands of American soldiers under my command, I can judge their ideology and vigor and I expect that at the decisive moment all Poles from America will stand up to appeal. In commending to you, Master, the mission that I am sending to America, I join you once again in my praise. Sincerely devoted

Gen. WP J. Haller

(Political Archives of Ignacy Paderewski, Wrocław 1973, vol. I, pp. 502-503)

In this short, informative, soldier-like letter, there are four tracks that will lead us closer to the historical truth on the topics touched upon, and those not touched upon, in the above-mentioned interview. These tracks are: the evaluation of Paderewski's work in America as "enormous"; pointing to America as a "friendly" force; a statement that the sender of the letter has under his command "thousands of American soldiers"; finally, there is information about Haller himself.

Let's follow these tracks.

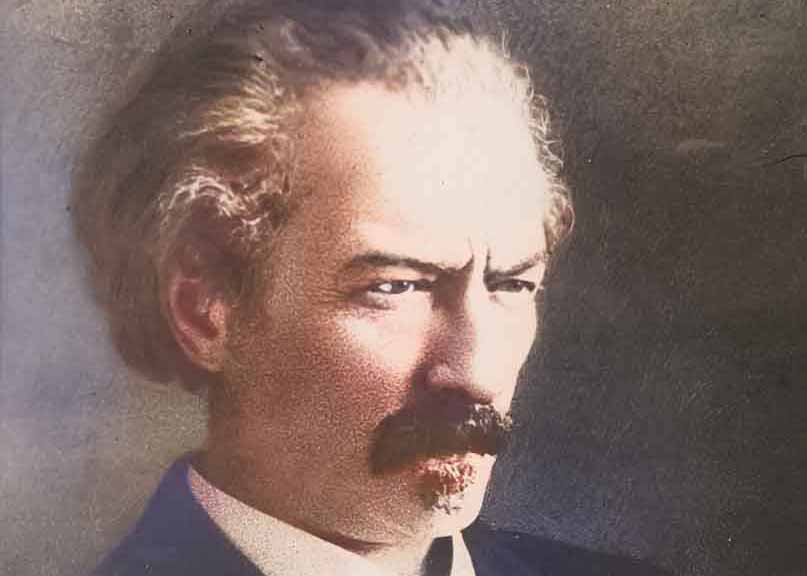

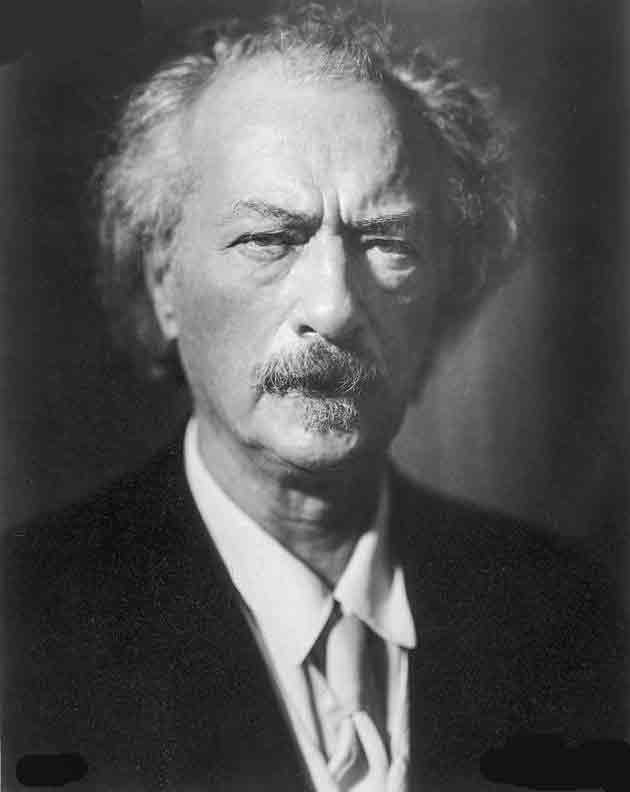

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (Source: Wikipedia)

The First Track - Paderewski's "huge amount of work"

The world-famous pianist and composer, and - at the same time - a great patriot and philanthropist, came to America in April 1915 from Switzerland, where he and Henryk Sienkiewicz created the Rescue Committee for Poland, via Paris and London, where he established similar committees (for the sake of brevity I do not mention their full names). Such a committee he set up in America. From the very beginning, he undertook work and activities for the independence of Poland, referring to his earlier act in this respect: founding the Grunwald Monument in Krakow (1910) and making its unveiling a great, nationwide demonstration, the first of its kind since the Third Partition. In America, Paderewski mobilized the Polish community (around 4 million) and the American public for Poland by calling rallies where he spoke and then played. He has had over 300 such appearances within three and a half years. He successfully led to the unification of almost all American Polonia organizations (fifteen in total) - including the Falcon and the Polish National Union - which, on July 1, 1917, granted him a formal power of attorney to represent them before the US government and allied governments. That was what Paderewski did constantly by participating in conferences, conducting extensive correspondence. He continued his "enormous work" after arriving in Poland at the end of 1918 - "to the joy of all of Poland". He had a quadruple mandate: to represent the majority of Poles in the country and abroad; the authorization of the Polish National Committee from Paris, formally recognized by the Allies as the provisional government of Poland; the full support of all victorious Allies, including President Wilson himself; a military basis in the form of the Polish Army in France.

Józef Piłsudski was already in power in Warsaw. He held the office of the Chief of State (so named after Kościuszko) and patronized the socialist government of Jędrzej Moraczewski. Initially, Piłsudski did not want to share power with Paderewski. Soon, however, he realistically assessed Paderewski's personal values and his political dowry. He appointed him Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, which happened on January 16, 1919. The appointment of Paderewski as the head of government brought the recognition of that government by Western countries and enabled discounts on material aid and loans granted to Poland. While managing the government, Paderewski undertook the gigantic work of organizing the law, administration, economy, and above all, uniting the lands and the people of the three former partitions.

From the beginning of Ignacy Paderewski's cooperation with Józef Piłsudski - forced by the international situation and the will of Poles at home and abroad - Paderewski was treated by Piłsudski as a rival. Piłsudski, however, tolerated Paderewski - as long as only he could perform another great task: bringing about diplomatic recognition of Polish authorities on the international arena; building foundations for the political, state and economic structures of the country; the negotiation of borders at Versailles, allowing the state to function independently; providing Poland with foreign economic and food aid and granting it financial loans. He did "a lot of work".

After returning from the Versailles Conference to Warsaw in July 1918, Paderewski struggled with increasing difficulties posed by Piłsudski and his legionary clique, part of the press, part of the Sejm. As a result, he decided that he could not perform his office effectively, resigned on December 9, 1919, and left the country shortly after that. He took up service to the nation again during the war with the Bolsheviks as the Polish Delegate to the Council of Ambassadors (1919), and then in the League of Nations (1920-1921).

The Second Track - "Friendly America"

Acting in America, Paderewski came into direct contact with the US government. As early as 1915, he established contact and cooperation with Col. Edward House, adviser to President Woodrow Wilson, and afterwards, in 1916, with the President himself, with whom he met three times at the White House - in March and July, when he toured and then spoke to the President; in October, when he had a longer political conversation with him about Poland; and in November, at his headquarters in New Jersey, also, of course, about Poland. At the request of President Wilson, given to him by Col. House, Paderewski prepared a memorandum on Poland (dated January 11, 1917), which contained an outline of the history of Poland; geographical description of the Polish lands; analytical historical, geographical and political presentation of the three partitions - Prussian, Austrian and Russian; a call to resurrect Poland within its pre-partition borders, with access to the sea. Following this document, Paderewski prepared another memorandum for President Wilson in the following days, justifying the need to grant future Poland East Prussia and Gdańsk. These memos resulted in an official declaration made by the President in the US Senate on January 22, 1917 calling for the creation of a "united, independent and autonomous Poland". Then President Wilson included the Polish cause in his Peace Plan, announced on January 8, 1918. Point 13 of this plan defined the emergence of "a united and independent Poland with access to the sea" as one of the conditions of peace. Indeed, as Haller writes in his letter, America was then "friendly" to Poland.

The Third Track - "thousands of American soldiers"

From the beginning of his operations in America, Paderewski began to work on the project of creating a Polish army in the USA, which, if transferred to Europe, would be a serious bargaining chip in Poland's efforts to regain independence. Since the United States was not yet formally participating in the war while maintaining its neutrality, the formation of this army, or training of volunteers, could not take place on their territory. On the other hand, Canada, neighboring the United States (as the dominion of Great Britain), was a party to the war. At the same time, the idea of creating a Polish army in Canada was already alive since 1914. The idea of creating Polish armed forces was also sprouting in France. Based on a combination of these circumstances, Paderewski decided to create a Polish army in Canada, under the auspices of the Canadian Army, of course with the knowledge of Great Britain, and in agreement with France (which provided the blue uniforms - hence the name "Blue Army" - and weapons). A military training camp was organized in Canada, just across the Niagara River, the US border, near the town of Niagara-on-the Lake, Ontario. The second military camp for Polish volunteers was established in St. Johns, Quebec. These were formally camps of the Canadian Army, but Polish volunteers from the USA, and in much smaller numbers also from Canada, trained there. The Falconry organization assumed the patronage over the entire action in the area. At the very beginning of 1917, 23 Falcon volunteers sent from the USA to Toronto, Ontario, arrived to undertake officer training. The next group trained as officers under the patronage of Falcon in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, based on a donation from Paderewski, from mid-March 1917. Paderewski ultimately revealed the idea of creating a Polish army on the American continent, speaking on April 4, 1917 at the extraordinary Sejm of Falconry in Pittsburgh, publicly announcing the initiative to establish a Polish Army in the United States under the name "Kosciuszko's Army" . Immediately afterwards, the U.S. entered the war on April 6, 1917.

On June 4, 1917, the President of France, Raymond Poincaré, on the initiative of Roman Dmowski, issued a decree establishing the "Polish Army in France" - it was initially an army almost without soldiers. Paderewski, constantly in touch with Dmowski, made an agreement with the founders of the Polish Army in France and agreed that the Kościuszko Army he was creating would be the core of the Polish Army in France.

On October 6, 1917, this army was officially recognized by the United States as an autonomous unit and thus received formal permission to recruit in the USA. Since then, recruiting has gained additional momentum. They were supported by the authorities, in addition to Paderewski, by Jan Smulski, an outstanding Polish community activist, and Andrzej Małkowski, the founder of Scouting, who came from the old country. In addition to the camp in Niagara-on-the Lake, Ontario, a new training camp was established in the US, at Fort Niagara, on the American side of the Niagara River. Thousands of new volunteers arrived there. On November 4, 1917, the Polish flag was solemnly raised in the military camp in Niagara-on-the Lake. On November 21, Paderewski received a parade of soldiers from Kościuszko's Army there and spoke to the army. On February 23, 1918, the political control over the Polish Army in France was established by the Polish National Committee. Paderewski visited his army again in June 1918, received the parade and said: “I come to you with a word of love on my lips, with immeasurable gratitude in my heart. (...) Go ahead! Go with faith in the sanctity of our cause, go with faith in victory! " (Archiwum Polityczne, ibidem, Part 1, pp. 368-369).

Successive transports of the Kościuszko Army left the training camps and headed for France. Ultimately, a total of 20,720 officers and soldiers were dispatched. This army augmented the Polish Army in France (under the French command) and was directed to the front, fighting the Germans in Champagne as a separate military unit under French command, as part of the French 4th Army. From the very beginning, Poles suffered losses such as, for example, on July 11, 1918, Lieutenant Łucjan Chwałkowski, a poet, one of the first officers of the Kościuszko Army. The total losses were to amount to about 3,600 soldiers.

The Polish Army in France quickly grew with additional thousands, as the news of its existence spread throughout the fighting Europe, and all over the world. Massive numbers of Polish deserters from German and Austrian troops started to arrive there. On the other hand, the Entente countries (on the Western Front - France, Great Britain, Italy, then the USA) agreed to release to the Polish army the prisoners of war - Poles, forcibly taken by conscription in Germany and Austria, and now reporting to the Polish army in POW camps. Volunteer groups from England, Argentina, Brazil, the Netherlands and Russia also came. In less than four months, in the summer and fall of 1918, a total of over 60,000 people arrived in France, which made the Army a powerful force of around 80,000,000. (Some sources estimate it at 100,000). They were mostly well-trained soldiers. Thanks to this army and thanks to the recognition by the Western states of the Polish National Committee as the provisional government of Poland (recognition by France - September 20, 1918, Great Britain - October 15, Italy - October 30, USA - November 10), Poland took part in the victory parade in November 1918 in Paris. (Which the allies disgracefully refused her in 1945 under pressure from Stalin).

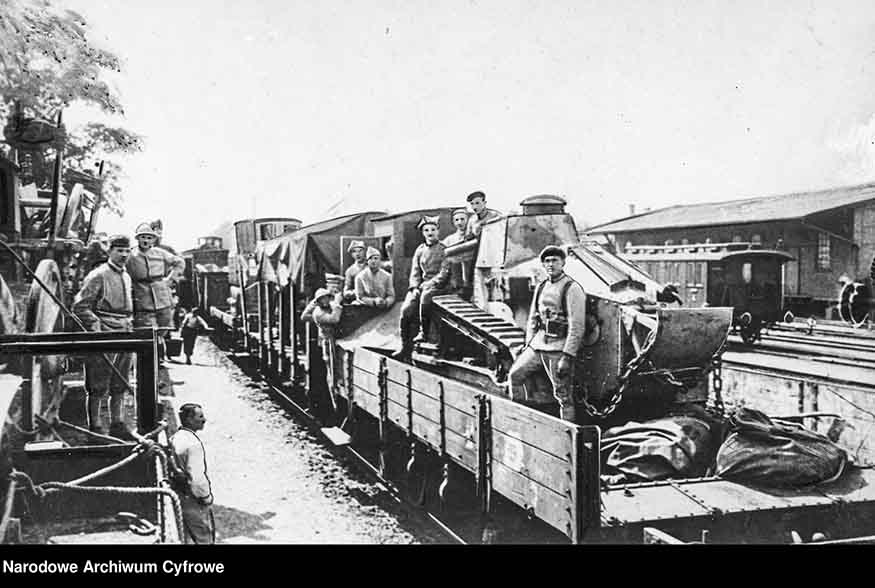

The army had excellent equipment (approximate figures, sources differ slightly): 88 heavy guns, 172 75 mm field guns, 106 37 mm infantry guns, 120 tanks, 98 aircraft, machine guns in each team. The army had, among others, engineering and communications departments, 7 military hospitals, plus 10,000 horses for cavalry. Thanks to the efforts of Paderewski and Dmowski, the army was transported to Poland (April - June 1919).

Acting as the Head of State and Commander-in-Chief, by the order of September 1, 1919, Józef Piłsudski practically liquidated the Blue Army. It was disbanded, dismembered and scattered among various divisions of the Polish Army, and thus annihilated as a separate military unit. Its commanders were dispersed and legionary officers were put in their place. The soldiers of the former Blue Army, included in various divisions, were an extremely valuable and experienced force inside the Polish army. They became the decisive factor in the many battles of the war with the Bolsheviks that was about to break out soon. Not everyone, though.

For Piłsudski made the decision to forcibly demobilize, intern, and then send back to America 12,000 American volunteers - the Kościuszko Army, previously trained in Niagara-on-the Lake, gathered and, in a way, blessed by Paderewski. Everything indicates that they were treated in this way as the core of the former Blue Army, which was the most loyal to Paderewski. Their evacuation from Poland lasted from March 1919 until February 1921. At that time, the war with the Bolsheviks was already fought; from July 1920, the "Volunteer Army" was organized, yet the best soldiers of the Blue Army were held interned at the same time, packed onto ships, and practically thrown out of the country. What is even worse, in the following years, these people were denied military pensions by the government of the Republic, and the families of the fallen were denied posthumous compensation, provided for by law. It was a terrible disappointment. It undermined the traditional attachment of the American Polish community to their homeland.

The Fourth Track - the figure of General Józef Haller

He came from Russia to Paris on July 13, 1918. Dmowski involved him in the work of the Polish National Committee (KNP, Komited Narodowy Polski) he was creating, which was officially established on August 15 in Lausanne and soon transferred to Paris. Paderewski became a member of the KNP and a delegate to the United States, and he also introduced Franciszek Fronczak, from Buffalo, a physician and major in the US army. On October 4, 1918, KNP appointed General Haller the commander of the Polish Army in France. From the moment Haller took command of this Army (of course not earlier) it began to be called "Hallerczycy" or "Army of General Haller", adding these names to the "Blue Army" moniker. In France, the general commanded this army during the war (until November 11, 1918), trained and reorganized it, and then prepared its transport to the homeland.

General Haller arrived in Warsaw on April 21, 1919, greeted like a hero. Almost immediately, with part of his army (with a corps of 35,000 soldiers), he was sent to the eastern front in May and fought the Ukrainians and the Bolsheviks with great combat successes. In June 1919, however, Piłsudski recalled him from the command of the Blue Army and directed him to the command of the South-Western Front, then inactive. So General Haller was in command of the Blue Army for only eight months (from October 1918 to June 1919), but his legend as a leader, and the legend of this army has survived for years - it has survived centuries - we are talking about him and his army in the 21st century.

After Piłsudski was removed from the command of the Blue Army, General Haller remained without assignment for several weeks and, on October 19, he was appointed commander of the Pomeranian Front, which was then established. It was with this army that the general reached Puck and on November 10 symbolically married Poland and the sea. During the war with the Bolsheviks, he was an energetic "Inspector General of the Volunteer Army" established at the appeal of Wincenty Witos (and not the commander of his well-trained Blue Army), and then he was given marginal positions in the army - he was, among others, the Inspector General of Artillery. After the May Coup d'état (1926), which he opposed, he was sent to retirement. Born in 1873, he was then 53 years old. One more great Pole bypassed in service for Poland - removed at the top of his strength, energy, talent, and skills.

Finally, a question must be asked:

How did it happen that - for many people - Paderewski's participation in "Poland's rise to independence" was for years underestimated, diminished, forgotten? After all, it was the appearance of Paderewski - such an outstanding, well-known, charismatic figure - on the political scene of the American Polonia, in America, Poland, and in the world, that became one of the fundamental factors that determined the resurrection of Poland as an independent state. His constant pursuit of higher values was backed up by incredible hard work. His artistry was harmoniously combined with knowledge. His manners, attention and respect for each interlocutor (he spoke seven languages) allowed him to communicate freely with both supporters and opponents. Paderewski focused the will of Poles in the country and in exile. He effectively participated in the international game for power and for numerous nations awakening from their lethargy of slavery. Providence and History found a special intermediary in him.

After Paderewski's resignation and departure from the country in 1920, a curtain of silence was drawn over him in Poland. Piłsudski and his camp treated him as a - still existent - potential political threat. His memory was blurred by all means available. His merits were forgotten. He was kept away from Poland. Only once did he come to Poznań, close to his heart, to accept an honorary doctorate awarded to him by the University of Poznań (1924). In a way, he repaid Poznań by donating a statue of President Wilson in the park named after him (1931).

Paderewski criticized Piłsudski's May coup in 1926, which widened the gap between him and the ruling camp. This gulf was still insurmountable even after Piłsudski's death (1935), when Poland was ruled by his apologists. Then (1936) Paderewski supported the efforts of General Józef Haller, General Władysław Sikorski, and Wincenty Witos, who put forward a program of healing Polish politics, creating - together with Paderewski - the so-called Front Morges (1936). The meetings of this body were held at his Swiss headquarters, under his patronage.

The lost war with Germany and the Soviet aggression against Poland in 1939 again created the need to refer to Paderewski's authority. With his strength already weakened, he refused to accept the office of the President of Poland that was offered to him. However, he did not evade the presidency of the National Council of the Republic of Poland in Paris in 1940. Soon, as a national emissary, he went to the USA to mobilize American, world-, and Polish opinion for Poland and to try again, as in the years of World War I, to gather volunteers to fight for Poland . The disgraceful stance of the Polish authorities on pensions and severance pay for volunteers from that war resulted in a complete failure of this initiative.

Ignacy Paderewski died in New York in 1941, after a murderous year for him at that time, filled with travel, talks, conferences and speeches. Following a personal decision of President Roosevelt, he was buried with the highest state and military honors America can offer to a head of state, at the Arlington Military Cemetery in Washington.

For the second time, the curtain of silence was drawn over Paderewski, or rather over his memory, by the post-war [Polish] communist government. Paderewski made his mark on those pages of the Polish history that the communists tried to remove from textbooks and tried to tear out of the hearts and memories of Poles. Therefore, his extremely important role in the resurrection of Poland in 1918 could not be mentioned.

What is the situation today?

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.