Sometimes, in order to better understand the situation in which the American Polonia found itself after 1989, it is worth analyzing how the relations between the Polish State and the Polish community developed after Poland regained independence in 1918. Reliable research by several independent teams of scientists, and a political will, are needed in this matter.

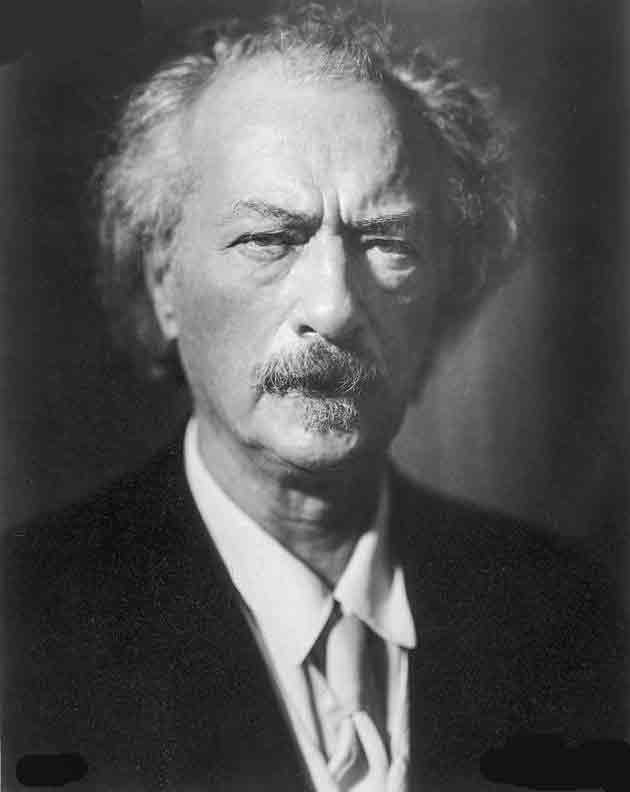

In the first years of Polish independence, as a result of the actions of the Polish Prime Minister-emigrant, Jan Ignacy Paderewski, hundreds of Polish scientists, industrialists and other professionals returned to Poland, bringing with them not only sincere intentions, but also knowledge, contacts, and money. The appointment of a world-famous artist — Ignacy Jan Paderewski, a man with outstanding leadership qualities — as the head of government brought the recognition of that government by Western countries and made it possible to open the way to material aid and loans granted to Poland. While managing the government, Paderewski undertook the gigantic work of tidying up the administration, economy and, above all, unifying the lands and people of the three former partitions and three different legal systems.

Paderewski was a Polish delegate to the Versailles Peace Conference (1919), where, together with Roman Dmowski, He fought tirelessly for Polish borders, for promoting Poland as a full-fledged and sovereign state after 123 years of political non-existence. Cooperation with the Polish diaspora developed. After Poland gained independence in 1918, the state authorities of the Second Polish Republic pursued a policy favoring Polish emigration. In 1922, on the initiative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MSZ), the Cultural Protection Council was established, including national institutions dealing with the Polish diaspora and representatives of ministries. In 1924, the Union for the Defense of the Western Borderlands put forward the idea of convening a Congress of the Polish Diaspora, and in 1925 the Organizing Committee of the Congress of Poles from Abroad was established, which began efforts to establish an organization bringing together Poles abroad for the purpose of promoting Poland as a full-fledged and sovereign state after 123 years of political non-existence.

However, the situation changed significantly after 1926, when the Sanacja regime came to power in Poland. According to Professor Wojciech Skóra, a Polish historian from the Pomeranian Academy in Słupsk, care for the Polish diaspora and Polish citizens in the USA deteriorated compared to the 1920s, as in 1922, there were 6 consular offices in the United States, and in the 1930s only 3 in Chicago, Pittsburgh and New York, as well as the embassy in Washington. In Poland's foreign trade, in 1935, the United States was the third largest partner in terms of exchange (after Great Britain and Germany). As for the largest economic power, inhabited by 126 million citizens (including almost 4 million Poles), it was definitely not enough. At that time, Poland had the same number of consulates in Italy.

Let us remind you that over 22,000 thousand volunteers from America, who, like the army from near Giewont, heard the famous golden horn from Wyspiański's "Wedding", came from overseas to fight for free Poland. General Haller's 70,000 "Blue Army" was, for those times, well equipped and trained. It had 120 tanks, 98 aircraft, engineering troops, instructors, cavalry, artillery, communications units, 7 field hospitals and a very high morale among soldiers. The "Hallers" brought 10,000 horses and ammunition to Poland. The further fate of the Blue Army is, unfortunately, a sophisticated political game by Józef Piłsudski. In June 1919, General Haller was deprived of the command over the "Blue Ones", which made his soldiers feel disappointed and deceived. The command staff of the Blue Army began to be replaced with loyal legionary comrades-in-arms. The last straw was added by the order of September 1, 1919, providing for the complete disassembly of the Army. Individual formations became part of other domestic military units. Polish volunteers from the United States were demobilized, which irritated the American Polish community. From March 1920 to March 1921, approx. 12,000 of the "Blue" Hallerians" sailed to New York. The situation of the demobilized soldiers of the Blue Army was very bad. The Hallerians from the USA, who were emaciated with the onset of typhus, kept in transit camps, were looked after by ship doctors. The matter was discussed at the highest levels of the US government. Julius Kahn, Congressman from California, and Congressman Kleczka, from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, raised the issue. The issue of the return of demobilized volunteers was raised in the House of Representatives in the early 1920s. This political mistake of the Marshal (Piłsudski) undermined the trust of the American Polish community in him for years, and after the May coup, it caused distrust of the Polish diaspora in the authorities in Warsaw.

Spectacular activities of Polish patriots in the USA, led by Ignacy Jan Paderewski, resulted in the establishment of the Herbert Hoover Institution and the Organization of the American Relief Effort in Poland (1919-1923). This American government organization, together with other organizations, such as the Polish-American Children's Aid Committee, donated $250 million to Poland. During the investigations of Kuryer Polski, we managed to find the calculations of Dr. Aleksander Rytel (the famous founder of the Polish Physicians Association in Chicago) on other financial contributions for Poland in the first years after independence. On the basis of the study by Dr. Rytel, the funds sent to Poland include: the National Fund, local collections, food parcels, money orders, payments by consulates, money sent by banks, securities, the Polish 6% loan. The dollar amounts imported by returning emigrants approached $100 million. These data concern only the first years after Poland regained independence, but we must realize that the stream of dollars flowed to Poland until September 1939 and — according to World Bank data — a transfer of approximately 900 million dollars goes from the USA to Poland every year.

The image of the Marshal among the Polish diaspora in America was only reinstated by 150,000 former Polish soldiers, officers and their families, who came to the United States after the Second World War.

II World Congress of Poles from Abroad and the establishment of Światpol

The convention began on August 5, 1934 in Warsaw, and the ceremonial closure took place on August 12, 1934 in Gdynia. 171 people participated in it: 128 delegates from 20 countries, including 40 from the United States, 25 representatives of domestic institutions and 18 members of the Organizational Council of Poles from abroad. A total of 11 thousand people came to Poland. The congress was accompanied by: the 1st Rally of Polish Youth from Abroad - 3 thousand people (the 2nd Rally took place in August 1935, combined with the Scouting Rally in Spała) and the 1st Sports Games of Poles from abroad (381 competitors and their families who took part in trips around the country). During the ceremony at Wawel, the World Union of Poles from Abroad (Światpol) was established, the president of which was Władysław Raczkiewicz, the Speaker of the Senate of the Republic of Poland.

It was managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In September 1933, Wiktor Tomir Drymmer became the head of the reorganized Personnel Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He was a man completely subordinated to Józef Piłsudski. Both the government's emigration policy and the personnel policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were in one hand. Thus, a plan was quickly developed in Warsaw to implement Polish foreign policy based on the Polish diaspora.

Franciszek Świetlik, the Dean of the Law Department of Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Kuryer Polski archives)

Everything would be perfect, as planned at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. All delegations were to join Światpol and create one world organization of Polish diaspora to implement the foreign policy of the Sanacja (The Cure) government. However, the Dean of the Law Faculty at Marquette University in Milwaukee spoke on this matter. What one of the then important leaders of the American Polish diaspora said has gone down in history as a goal for many important figures of Polish diaspora in the USA. Franciszek Świetlik, a lawyer born in Milwaukee, well known in America, said then:

We are proud of our ancestors and we want the young generation to keep in their hearts love for everything that is Polish but, at the same time, we feel that we can aid Poland by taking active creative participation in American life and culture. The higher our status in America as Americans, the more glory and benefit we will bring to the Polish nation from which our roots come.

It is his definition of who American Poles are that is still valid today. We are Americans of Polish descent and, although some of us have two passports: Polish and American, we can continue to serve Poland as our ancestors did in the USA.

Out of 40 delegates, no person or organization from the USA joined Światpol. Why? It was not only the most numerous segment of the Polish diaspora, but also the richest, and with a complicated social and professional structure. It was the only Polish community with a well-formed, strong elite. There lived a large and influential layer of professional intelligentsia and relatively wealthy traders. There were many clergy, lay, and religious participants. According to the Consul General of the Republic of Poland in Chicago, Dr. Wacław Gawroński, the Polish diaspora in the USA in 1935 amounted to about 4 million and had a very well-formed elite. 250 journalists and 90 magazines were published in the United States, which have a serious influence on the course of life here. Clergy numbered over 2,000 priests and 6,000 nuns, teachers in 832 parishes, in addition to about 1,500 people in religious congregations and about 120 clergy of the National Church - about 10,000 in total. The remaining intelligentsia, constituting less than 1% of the total exile numbers, if we include doctors, dentists, pharmacists, lawyers, engineers, teachers, musicians, officials, industrialists, and some merchants, will account for about 30,000 people. There were also large organizations (ZNP 300,000 members, ZPRK 170,000 and the Union of Polish Women - 60,000 members), which together covered about 500,000 people.

The goals set by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were not fully realized and the idea of managing the Polish diaspora from behind a desk in Warsaw did not bring the assumed victory. Attempts to teach the Polish diaspora what is "Polish duty as the highest value" by the Sanacja diplomacy faltered due the misunderstanding of the Polish diaspora. The entire history of Polish emigration shows that "the ability to put the Polish raison d'état in the highest esteem" existed many years before the creation of the independent Polish state. The postulate of an "independent state" was put forward by the first Polish National Congress in 1910. The National Department, the National Defense Committee, the Falcons of Poland, the Polish National Council, the magazine for Americans "Free Poland", and the "Blue Army" of General Haller - where the vast majority were US volunteers - were all acting for Poland's independence. However, the greatest achievement for Polish independence in America were the words and deeds of American President Thomas Woodrow Wilson who, in the 13th point of his program for the Versailles conference, said:

An independent Polish state to be established whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity shall be guaranteed by international covenant; which shall include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations; and which shall be accorded a free and secure access to the Sea.

It was the greatest success of Polish lobbying in the United States which brought us independence. It was possible only as a result of the development of the demand of the 13th point, which was initially formed at many conferences and parliaments of the American Polish diaspora, which took place in many American cities between 1910 and 1918. It was there that the Polish idea of independence grew up, and it was there that the 13th point of President Wilson's program was created. The talks between Ignacy Paderewski and President Wilson were also extremely important. It is time to finally acknowledge this and not to silence the contribution of the American Polonia in the process of the formation of the Polish state.

The meeting between a delegation of the Association of Poles Abroad and Marsh.. E. Śmigły-Rydz in Warsaw, 1939 (Source: Wikipedia)

In March 1941, a Polish recruiting mission arrived in Canada, the still-hospitable country bordering the once-again neutral USA. The recruitment mission of the Polish Armed Forces in the USA and Canada took place in 1941-42 and was commissioned by General Władysław Sikorski, after his visit to America, where he was enthusiastically welcomed by the Polish community and, on this basis, assumed that the recruitment would result in an influx of volunteers to the Polish Armed Forces in Great Britain. The mission turned out to be a failure. The American Polonia learned from the experience of the Blue Army.

Despite bitterness and pain, and a sense of moral harm, the American Polonia has always supported and supports a free and sovereign Poland. An example of this can be the activities of the Polish community in 1944 and the establishment of the Polish American Congress (KPA, Kongress Polonii Amerykańskiej) in Buffalo. During the Cold War, during martial law, during Poland's efforts to join NATO and efforts to deploy American troops in Central and Eastern Europe, the KPA played a key lobbying role. Nine million signatures on a petition supporting Poland's request to join NATO were of importance. However, it was not possible to properly coordinate the joint activities of the Polish diaspora and Polish diplomacy to have a friend of the "Polish cause" in the person of the President of the United States during World War II.

The marginalization of the participation of the Polish diaspora in political and social life does not serve Poland, let alone Polish raison d'état. To promote Poland's strategic interests in the US, a well-thought-out, long-term strategy is needed, based on a sincere willingness to cooperate with the Polish community. The results of the research conducted by the Piast Institute in Michigan, confirm the image of the Polish diaspora that are modern, educated, wealthy and proud of their heritage. It seems that the Polish diaspora has the potential that can not only help strategically support Polish interests in Washington, but also help change the image of Poland in the eyes of the average American. For this, however, we need a cross-party vision of cooperation with the Polish diaspora, the liberal and conservative one, in the country on the Vistula River. Treating the Polish diaspora as if of secondary value is in the interest of those, who would like to weaken our country.

Kuryer Polski was reborn in September 2020 to unite the Polish diaspora again around the "Polish cause" and to facilitate the establishment of contacts at the level of culture, economy and politics with the Polish authorities. Our goal is to build a communication platform between the Polish diaspora and Poland. Above all, we need to get to know each other better to start building a global network of connections between Poland and the Polish diaspora.