Woodrow Wilson, born in 1856, was an academic-turned-politician who served as the 28th President of the United States from 1913 to 1921. He enjoyed immense popularity and was regarded as a legendary figure in Poland, particularly during the 1920s. The reasons for this reverence can be attributed to Wilson's stance on U.S. policy during World War I, the perception among Poles of America's special benevolence, and Wilson's personal involvement in Polish affairs. His speeches to the Senate on January 22, 1917, and to Congress on January 8, 1918, further cemented his popularity in Poland, as his words were seen as instrumental in bringing about the swift end of the war and the restoration of Poland's independence.

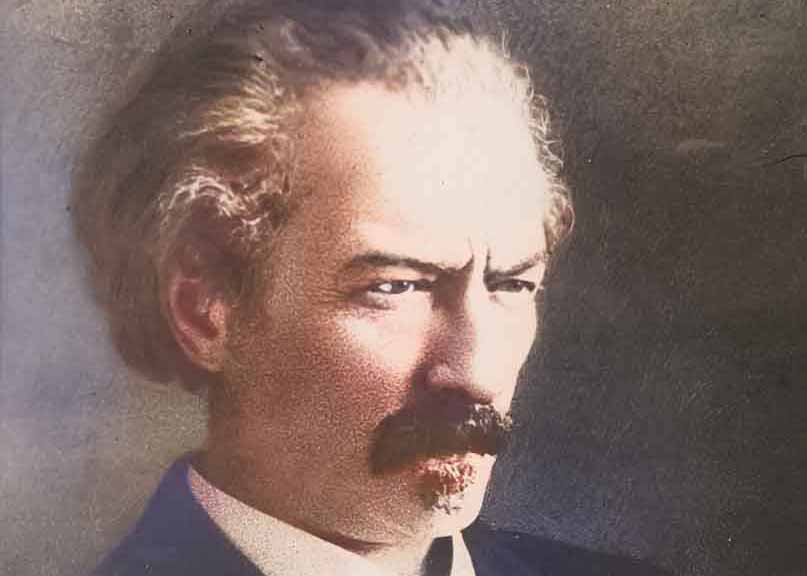

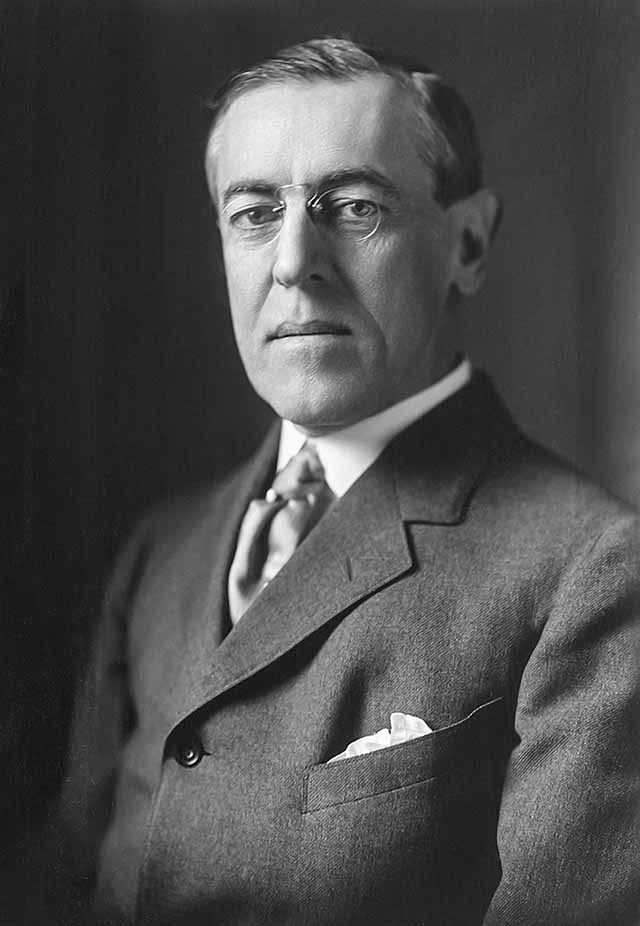

Portrait of Thomas Woodrow Wilson (Color: A.Woźniewicz). (Source: The White House)

Wilson had numerous accomplishments during his presidency. In 1917, Wilson's book on the nation-state was translated into Polish, reflecting his vision of an activist presidency rooted in the Progressive Movement. Wilson advocated for administrative methods in the American government and implemented visionary internal reforms in areas such as banking, currency, tariffs, and workers' rights. His role in world affairs was unprecedented, as he faced crucial decisions early in his presidency that could shape the future of the world.

Just a year into his presidency, Woodrow Wilson found himself faced with decisions that held the power to shape the world's destiny. Initially, when World War I erupted in Europe, President Wilson firmly believed that it was not in the best interest of the United States to become entangled in the conflict. However, Germany's unrestricted submarine offensive, which resulted in the sinking of American ships, and the shocking revelation of Germany's proposal to Mexico changed the course of history.

On March 1, 1917, the American public learned of Germany's audacious proposition to form an alliance with Mexico in the event the United States entered the war. British intelligence had intercepted a secret message from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government, outlining plans for an alliance that included Japan as well. The goal was to regain the southwestern states that Mexico had lost to the U.S. during the Mexican War of 1846-47.

Faced with such a grave threat to national security and the region's potential destabilization, President Wilson decided to take the United States into the war. This marked a significant turning point in his presidency and set the stage for America's active participation in the global conflict.

The circumstances forced him to put aside his domestic reform agenda and temporarily centralize power in Washington. The administration created special agencies to manage mobilization during the war. These included the War Industries Board in 1917 and the Food Administration's extensive relief program led by Hoover. Wilson introduced a new income tax to finance the war, covering around half the $33 billion spent. The remaining costs were met through Liberty Loan drives, which encouraged the public to invest in America by purchasing Liberty Bonds. Wilson even donated the wool from the sheep grazing on the White House lawn to a Red Cross fundraising auction, as the gardeners responsible for the lawn had been drafted into the military.

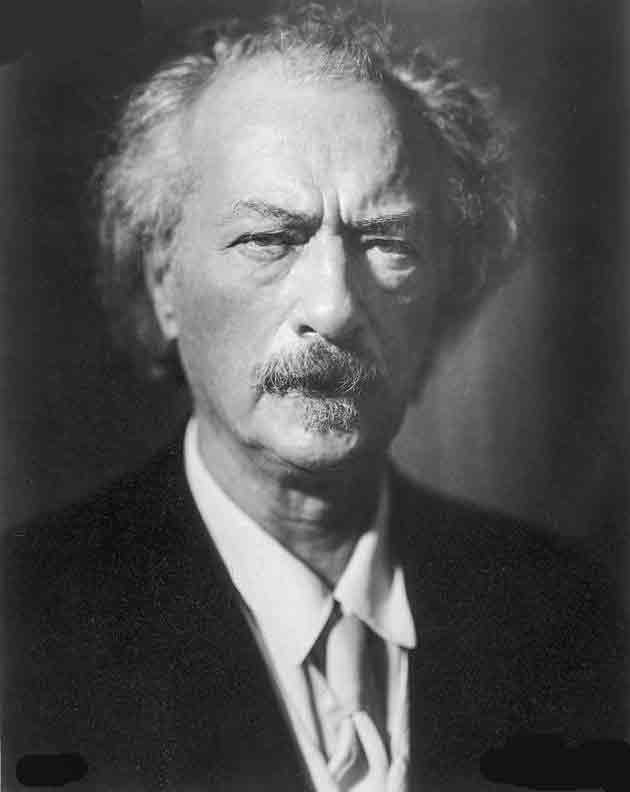

President Woodrow Wilson, portrait by Harris & Ewing, 1914 (Źródło: Wikipedia)

In December 1918, President Wilson traveled to Europe to participate in the Paris Peace Conference and contribute to establishing a new global order after the war. During the conference, he met with representatives from 26 other countries. Wilson believed that after the immense catastrophe of World War I, mechanisms could be put in place in world politics to prevent future disasters.

Even before the conclusion of the Paris Conference and Wilson's return to the US, there were efforts from Polish political circles to persuade him to visit Poland. While his visit did not materialize, future 31st US President Herbert Hoover visited Poland in August 1919 on Wilson's behalf, receiving a warm welcome.

Wilson's Square sign in Warsaw (Photo: A. Wozniewicz)

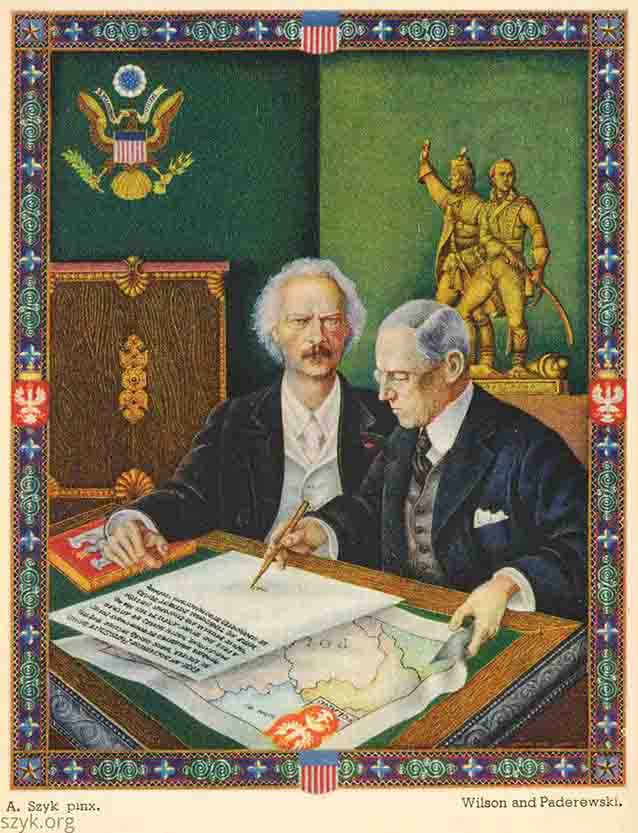

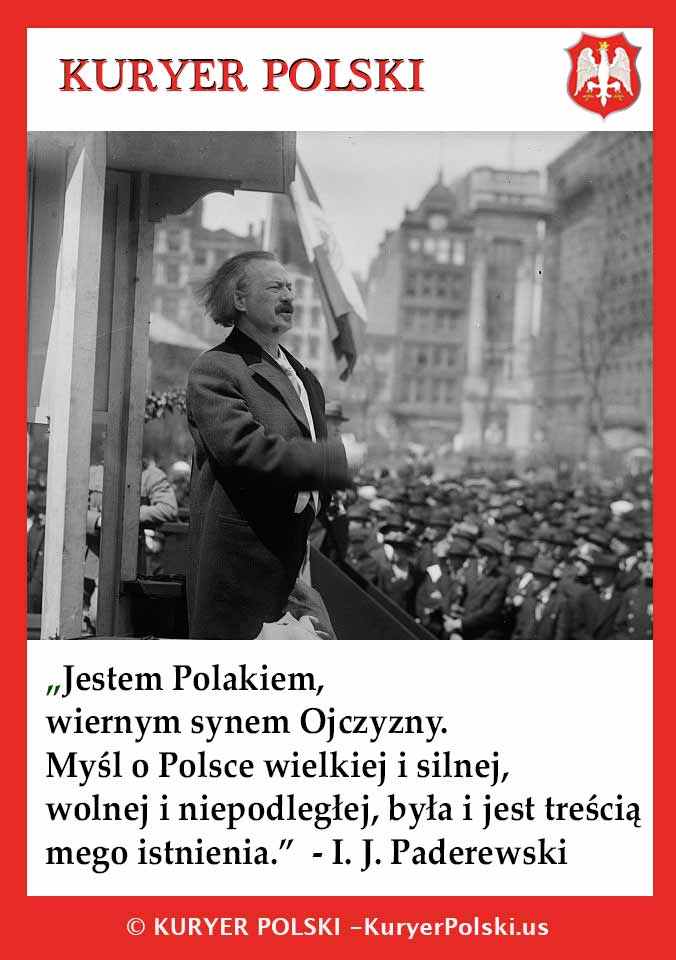

Prominent figures such as Roman Dmowski, who sought Wilson's support for the Polish cause, and Józef Piłsudski, who recognized his international role, actively contributed to the Wilson legend in Poland. Ignacy Jan Paderewski played a crucial role in creating and maintaining Wilson's reputation, repeatedly highlighting his contributions to Poland. Paderewski expressed gratitude to Wilson in the Legislative Sejm on November 12, 1919, and through letters and dispatches in 1920, ensuring that Wilson's name would forever hold a place in the hearts of the Polish people. In November 1922, Wilson received the Order of the White Eagle, the only foreign decoration of its kind that he received at the time, presented on behalf of the Polish government by US MP Władysław Wroblewski at his Washington home.

Wilson's name and achievements were also commemorated during the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the United States in 1926 and the 10th anniversary of independent Poland in 1928. The Polish people held a deep reverence for Wilson, considering the United States a model of perfect democracy and a strong connection between the two nations. In the 1930s, various ceremonies and anniversaries continued to honor Woodrow Wilson and his contributions to the reconstruction of Poland. In July 1931, a monument to Wilson, whose author was the famous sculptor Gutzon Borglum was unveiled in Poznań, funded by Paderewski and attended by President Ignacy Mościcki, Foreign Minister August Zaleski and other distinguished guests, including his second wife, Edith Wilson. The event received significant media coverage.

Bust of Wilson in Poznań (Source: Wikipedia)

After returning to the United States from Europe, Wilson embarked on a nationwide trip to rally support for his ideas. However, he suffered a stroke and paralysis during the trip, which incapacitated him for several months and prevented his active participation in presidential activities. His wife, Edith, essentially ran the Executive branch of government for the remainder of Wilson's second term.

The US Senate's failure to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and reject membership in the League of Nations dealt a significant blow to Wilson. In March 1921, he left the White House, feeling disillusioned and disappointed by the American people's lack of support for his political plans. Despite his previous popularity and recognition, Wilson quickly faded into obscurity after withdrawing from political life. In 1919, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role as a founder of the League of Nations. Wilson passed away in 1924, five years after receiving the prestigious honor.

Article originally published by the Minnesota Polish Medical Society. Republished with permission.