What to do when we lose the fight for our country? Emigration is one of the solutions historically tried by Poles. Political emigration is a way out with the intention of returning — to a free country again. Returning with weapons in hand, with ready ideas for reform and contacts made in the world that are helpful to the country, and finally with money earned in other countries and under different conditions that will be useful as an investment in one's own homeland.

This is an experience practiced in our history since the 18th century, when the Republic of Poland, subjected to external control, lost its independence and there were people who decided to fight for this independence — but they lost.

The first great uprising was the Dzików Confederation, almost completely forgotten today, established in 1734 in Dzików, but which spread armed resistance to a significant part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was a statement against the open military intervention of Russia, which imposed a king on Poland in 1733 against the will of its citizens. Citizens chose Stanisław Leszczyński, and the Russian Tsarina — Augustus III Sas.

It was then, when Russian troops entered, that a young Piarist priest, Stanisław Konarski, re-popularized the concept of independence in his Confidential Letters from the Interregnum. He served the Confederates until 1736, seeking diplomatic assistance from France. When this failed, he returned from emigration to the country: with his head full of ideas on how to raise his homeland from decline. From his stay in the countries of Western Europe, he brought new concepts of education — and according to them, he prepared the first school for the renewal of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Collegium Nobilium in Warsaw, and reformed the entire network of Piarist education, combining the study of the modern world with education for civic duty in a modern system. To contribute to the convalescent reform of political institutions, he prepared the most important work of Polish political journalism of the 18th century: On an effective Council Method, driving into Sarmatian heads the need to reject the liberum veto, which is manipulated by our neighbors to enslave our country. Without Konarski, there would be no Constitution of May 3.

(Source: DlaPolonii.pl, fot. Zbigniew Osiowy)

Earlier, however, due to another armed intervention by Russia in Warsaw itself — the kidnapping of senators and envoys on Catherine's orders and the imposition of formal Russian "protection" on the Commonwealth — another great uprising broke out: the Bar Confederation, which lasted four years. It lost against the violence of a neighboring empire. However, it also retained in the actions of one of her emigrant MPs an example of what we can and should strive for when fate throws us out of an enslaved country.

In order to prepare the justification for the partition of Poland, Catherine II and Frederick II of Prussia created an extremely effective propaganda image of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a black hole on the map of the European Enlightenment, a den of ignorance and superstition that only Prussian and Moscow bayonets could sort out. Such a picture was sketched with the money of both partitioners by the first writers of enlightened Europe: Voltaire, Diderot, Baron Grimm.

The response to the actions of the confederate envoy, and then the emigrant — the great Lithuanian chef, Michał Wielhorski, followed. He did not obtain diplomatic help from Paris, but understanding how important the fight for the country's image in international public opinion was, he established contact with its then co-creators: Gabriel Mably and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Both famous philosophers, under his influence and based on the materials he provided, wrote works that will create an important counter-current to the "black legend" of Poland. In particular, Rousseau's book, Notes on the Polish Government, will become a lasting point of reference on the intellectual map of Europe, in which Sarmatian freedom is not condemned as "ignorance and anarchy", but appreciated as a manifestation of the republican spirit. And for Poles it will become yet another signpost for the future: "If you can't prevent your neighbors from swallowing you, make sure they can never digest you." Culture, national culture, is the most important thing — this was announced by Rousseau, persuaded by the Bar emigrants.

And we know from the history of the 19th century, after the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was erased from the map by the three empires, that this advice would prove to be beneficial in the long run, and emigration will play the most important role in its fulfillment.

Of course, we also know that subsequent waves of emigration, immediately after the fall of the Constitution of May 3 as a result of the invasion of Catherine's army in 1792, and then, after the final partition of Poland in 1795, were primarily concerned with political and organizational preparations for the resumption of armed struggle for independence and seeking help for it in the West.

The result of the first of these emigrations (concentrated in Dresden and revolutionary Paris) was the preparation of the Kościuszko Uprising.

The second emigration, after the defeat of the insurrection, will bring as its most important fruit the Dąbrowski Legions — those that finally "came from Italy to Poland" with Napoleon in 1806. This allowed for the reconstruction of the nucleus of the Polish statehood: the Duchy of Warsaw.

Although Napoleon lost the next confrontation with Russia and the matter of the Duchy was buried, the effort, symbolized by the Legions created by the emigration, was not entirely wasted. At the Congress of Vienna after the Napoleonic Wars, the name of the Kingdom of Poland was restored, although only as a small area under the rule of Tsar Alexander I. For the next 15 years (1815–1830), Poles again had a substitute for their statehood. Valuable, but insufficient for those who wanted independence and the integrity of the Republic of Poland. So another uprising broke out, called the November Uprising. And it was defeated by Tsar Nicholas and the most powerful army in the world at that time. The defeat of the uprising triggered the largest ever wave of emigration.

Since 1831, the division: country — emigration, and certainly of Polish culture, has appeared in the history of Poland and it was repeatedly renewed until the second half of the 20th century. Country — this is the area of Poland, which is not sovereign and therefore cannot freely develop its culture and political debate. Emigration replaces the country in these functions. Of course, we are talking about political emigration, not mass economic emigration, which would become an important social phenomenon only at the end of the 19th century. Emigration after 1831 included just over 10,000 people. Most of them, about 6,000, settled in France. About 700 lived in Great Britain, and several hundred also in Belgium. Smaller groups — in Greece, Turkey, Italian and German countries, as well as in Spain and Algeria, colonized by France.

Initially, only a few dozen insurgents reached the United States, with the support of the American-Polish Committee and led by James F. Cooper (author of The Last of the Mohicans). The specific quality of this emigration was more important than the number. It was composed largely of officers coming from the nobility and intelligentsia, volunteers of the insurgent army, participants of the political life of the Kingdom of Poland. They were almost exclusively men. Most of them remained bachelors. A group of about 200 Polish women emigrated; mixed marriages, with French women, were rare. Many Polish emigrants did not seek stability abroad, but lived with the thought, even obsession, of returning to the country: returning with weapons in their hands, to the liberated Poland.

While we can talk about a strong patriotic mobilization of a large part of the Polish social elite, certainly during the November Uprising, emigration after the uprising was characterized by almost feverish mobilization. It also had special intellectual capabilities to perpetuate this fever, spread it, and create an institution and a specific political culture out of it. It was an emigration of not only literate people, almost 100 percent of them, but also in a very large part of educated people — from the universities of Warsaw, Vilnius, and the Krzemieniec High School.

Already in France, out of 6,000 emigrants, 1,117 people have pursued higher education (most often in medicine and engineering). Further education — it was assumed — would be useful in the reborn Republic of Poland. In such a community, it became possible to publish nearly 100 different magazines (until 1848) and over 1,700 books and political pamphlets, which was helped by the fact that nearly 200 emigrants took up work as printers, lithographers and bookbinders.

Poles have not yet been able to create their own university in exile, but they have established several other, permanent institutions of culture, education and science. These include: The Literary Society, founded in Paris in 1832 (it had a Science Department and a Statistical Department in its structure; from 1854 it was called the Historical and Literary Society); since 1838 Polish Library has been operating in the heart of Paris, on the Island of St. Louis; from 1842, there was also a Polish secondary school in Paris for over 100 years.

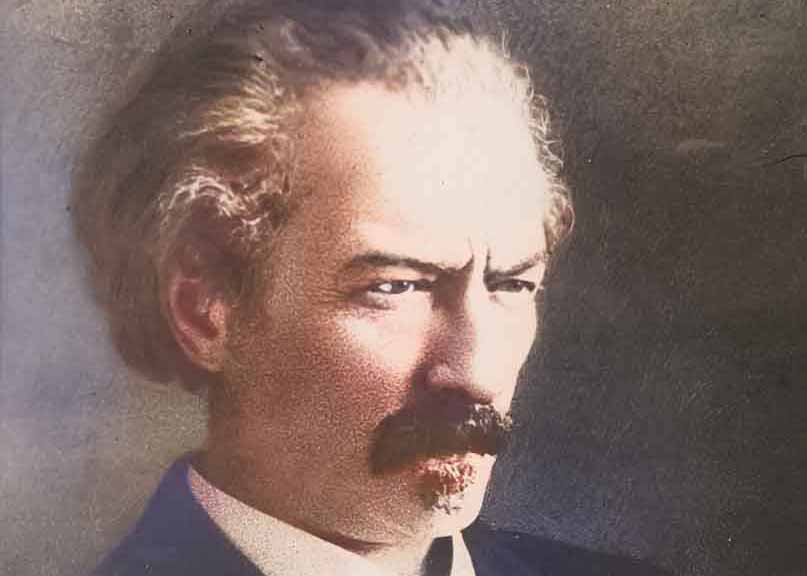

However, there was something else that escapes statistical calculations: the concentration of the greatest talents in this emigration circle, and in the case of a few people, one could say, the greatest geniuses in the history of Polish culture. These were Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Zygmunt Krasiński — three poets who were recognized in this history as the three "national bards". They will be joined a little later by the "fourth bard" — Cyprian Kamil Norwid. They were accompanied in music by Fryderyk Chopin. Apart from them, there are other talented poets, publicists and historians — co-creators and popularizers of new symbols and myths in the national imagination. They, above all Chopin, will undoubtedly create the most perfect "soft power" instrument for Polish independence, especially at a time when Poland, deprived of a state, had no "hard power" at its disposal.

Chopin at the age of 25, by his fiancée Maria Wodzińska, 1835 (Source: Wikipedia)

It is worth recalling, however, that such a role was also played by the successes of other Polish emigrants, of course on a smaller scale. Three examples can be given: Ignacy Domeyko, Paweł Edmund Strzelecki and Antoni Norbert Patek. They can be treated as evidence of a specific "globalization" of Polishness, which emigration fostered.

Domeyko (1802–1889), one of Mickiewicz's friends from the University of Vilnius, where he studied differential calculus, decided to take up new studies in exile, at the Mining School (École de Mines) in Paris. He used the knowledge he gained by going all the way to Chile. There he organized the foundations of modern mineralogy and the mining industry, and also reformed the capital's university in Santiago, serving as its rector for 16 years. Next to the next generation emigrant, Ernest Malinowski (1818–1899 — he emigrated after the November Uprising as a boy, together with his father), the builder of the Trans-Andean railway in Peru and Ecuador, Domeyko became a hallmark for Poles in Latin America, just as previously Kościuszko and Pulaski had for Poles in North America. However, the hallmark was not the saber, but a university diploma and engineering achievements.

Paweł Edmund Strzelecki (1797–1873) played a similar role for Australia. Strzelecki, originally from Poznań, left the country before 1830 due to unhappy love and his great passion for traveling. After touring Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, Hawaii and Tahiti, he reached New Zealand and Australia in 1839. In Australia, he explored mineral deposits in the Gippsland region (he discovered gold deposits there), and in 1840 he explored and measured the highest peak of the continent in the Australian Alps: he named it Mount Kosciuszko (2,228 m above sea level). Although he was not a political emigrant in the strict sense of the word, he willingly financially supported the activities of the Literary Society of Friends of Poland in Great Britain.

Antoni Norbert Patek (1812–1877) was an 18-year-old who won the Golden Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari for his service in the cavalry of the November Uprising. In exile, he settled in Switzerland. In Geneva, after years of practice, he founded his own watch factory, which used the most modern invention: head winding. In 1845, in partnership with the French inventor Adrian Philippe, he created a new watchmaking company that introduced watches with a separate second hand to the market. Patek Philippe gained a reputation during his lifetime, producing some of the world's first wristwatches. Today, it is the most exclusive watch brand in the world.

Did these careers result in anything for Poland? Results? Thousands of emigrants, of course, did not have any careers. Most lived in daily poverty, on small government benefits (in France) and odd jobs paid until 1856. The main diversion was political activity. Thanks to this activity, emigration became a laboratory of organizational forms of modern political life. And yet, the examples given here of action that go beyond involvement in "damning quarrels", i.e. political life, are not a form of departure from Poland, but a service to its culture, its good name, pride in this name — through individual scientific and technical achievements, artistic – they deserve to be reminded.

Of course, they do not end with the times of the Great Emigration, but they find further confirmation — from Maria Skłodowska to Tadeusz Sendzimir and Zbigniew Brzeziński. Poland is on the map. But it's good that we have these heroes.

Translated from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.