In August 1919, in a stuffy room at the Warsaw General Staff, young Lieutenant Jan Kowalewski sat hunched over a string of incomprehensible letters. Soviet cryptograms, full of seemingly random characters, streamed in from the Eastern Front every day. The Poles listened but did not understand.

One night, Kowalewski—a chemist by training, a linguist by passion, an officer by necessity—reached for... a comb. Yes, an ordinary pocket comb with broken teeth. He ran it across the page to see if any repeated letters appeared at even intervals. "The comb and Poe," he would later say with a smile, recalling Edgar Allan Poe's short story "The Gold-Bug," in which a similar trick leads to the solution of a mystery.

This was the moment when Polish cryptology was born – a discipline that two decades later would give the world Enigma breakers, and in 1920 gave Poland something even more valuable: independence.

A Child from Łódź Who Listened to the World

Jan Kowalewski was born on October 24, 1892, in Łódź – a city then seething with languages, smells, noise, and factory smoke. Poles, Germans, Jews, and Russians spoke four languages interchangeably there, and young Jan absorbed everything like a sponge. Even as a teenager, he spoke fluent German, Russian, and French.

He dreamed of science, not war. After graduating from high school in 1909, he traveled to Liège, Belgium, to study technical chemistry at the university there—a field where the future smacked of progress and laboratories, not trenches. He was encouraged to pursue chemistry by his father, a wealthy merchant from Łódź who traded in dyes for the textile industry. As a chemistry student in Liège, in the summer of 1914 he went on an internship at a Ukrainian sugar refinery in Bila Tserkva, where he first encountered the harsh everyday life of the Russian Empire—and never returned to Belgium.

In 1914, the world collapsed. The war found Kowalewski – like many Poles within the three partitions – in the uniform of the occupying power, in this case, Russian. He joined the Tsarist army, the engineering corps. Instead of conducting chemical research, he built bridges, repaired tracks, and operated communications. He didn't shoot – he listened, observed, memorized, and honed his fluency in Russian. In Russian structures, communications and radiotelegraphy were subordinated to sapper troops – hence, even before 1918, Kowalewski "touched" the codes, keys, and realities of radio work on a daily basis.

In this seemingly trivial experience lay the seed of his future genius: patience, precision, and a fascination with how information – be it well, or poorly conveyed – can decide between life and death.

From Kaniów to the General Staff

After the 1917 Revolution, Kowalewski joined the emerging Polish structures in Russia, joining the Union of Military Poles, and then the 2nd Polish Corps in Ukraine, serving in the headquarters' intelligence unit. He fought, was captured after the Battle of Kaniv, and escaped, taking documents and notes with him. After Kaniv, he joined the underground Polish Military Organization (POW) (KN III), eventually joining General Żeligowski's 4th Rifle Division.

In the summer of 1919 he arrived in Warsaw and joined the Second Department of the General Staff – the one responsible for intelligence.

One of Piłsudski's first decisions after arriving from Magdeburg was to build intelligence structures from scratch. He entrusted this task to Colonel Józef Rybak, who brought in former specialists from Austria-Hungary and recommended Lieutenant Colonel Karol Bołdeskuł, a veteran of the Eastern Front, as head of radio intelligence. It was into this institutional framework that Lieutenant Jan Kowalewski emerged.

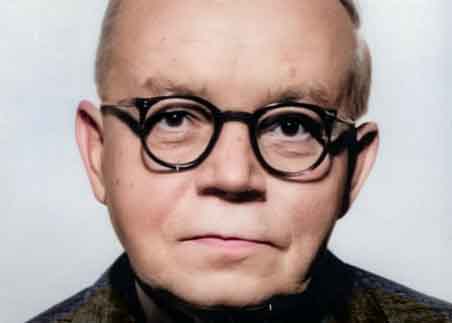

Jan Kowalewski (Source: Wikipedia, Color: A. Wozniewicz)

There, amidst the papers and dispatches, he quickly attracted attention not so much for his military drill, but for his extraordinary logic. Where others saw a chaos of letters, he discerned regular patterns.

War Against an Invisible Enemy

In August 1919, just a few months after returning home, Lieutenant Kowalewski achieved what we would today call a scientific breakthrough: he broke the first Red Army cipher.

He wasn't a mathematician with a degree, but he thought mathematically. He had no background, no equipment, and no team. He had only intuition and a thirst for knowledge. And once he read the first report, he knew he couldn't stop there.

The story of this first deciphered message deserves to be told. His colleague, Lieutenant Bronisław Sroka, was on duty that night at the Staff telegraph office (where intercepted messages from the intercepts were transmitted), but his sister was getting married. So he asked someone to replace him. Jan Kowalewski took his place. During this shift—out of pure curiosity and thanks to his excellent knowledge of Russian—he took on one of the Red Army's cryptograms.

Among the intercepted messages were two telegrams – one unclassified, bearing the signatures of Russian General Yakir and his Chief of Staff, the other intricately written in squared calligraphy. The first word – "Delegate" – gleamed in quotation marks. And that was enough for Kowalewski to realize he had stumbled upon something, akin to the Rosetta Stone, that could be solved.

Kowalewski wasn't acting blindly. He assumed the Russian message would contain the word "division"—the Russian "дивизия" with its characteristic pattern of repeated "i." He knew from directional listening that the message was coming from Odessa ("Одесса"—a double "s"). The Russians used a grid cipher: letters were mapped to pairs of digits, like in a multiplication table. So he used... a comb with evenly spaced missing teeth to detect the repeating sequence. He added a "pad" of the header and signatures (both plaintext and cipher), allowing him to reconstruct almost half the alphabet. It was the now standard linguistic attack, soon supplemented by a mathematical attack.

During the interwar period, Poland was a mathematical powerhouse – and it's no coincidence that cryptology arose from this foundation. In countries that must defend themselves, mathematics and logic become weapons.

Kowalewski soon built a radio intelligence system from scratch, unlike any young country in Europe. He recruited mathematics students and professors—Wacław Sierpiński, Stefan Mazurkiewicz, Stanisław Leśniewski—and taught them a new discipline: information warfare.

Poles didn't just listen to Soviet dispatches— they understood them. By the end of the war in 1920, Kowalewski's team had cracked over a hundred cipher keys, deciphering thousands of messages.

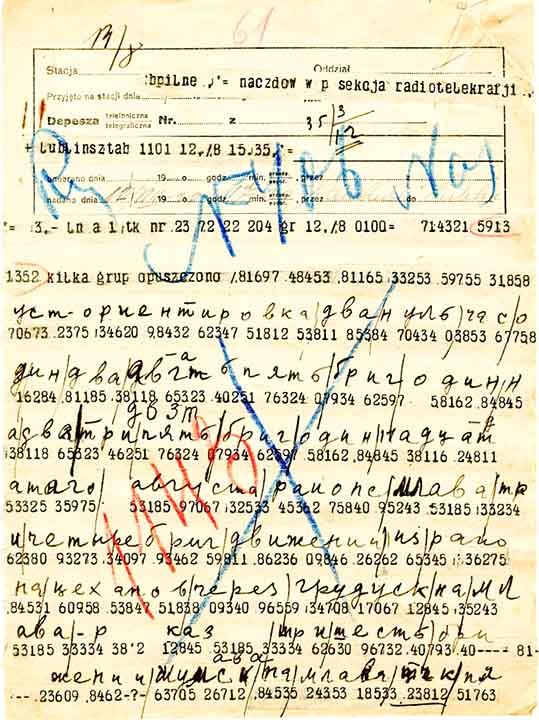

Red Army ciphertext intercepted and deciphered by cryptologists of the Second Department of the General Staff of the Polish Army in August 1920. (Source: Wikipedia)

In the mythology of the Battle of Warsaw, we usually speak of the "Miracle on the Vistula River" and the genius of Piłsudski or Rozwadowski. But there was also a third "miracle"—a quiet, mathematical one. A year earlier, in Warsaw basements, where telegraph keyboards clattered, Poles had cracked the Red Army's ciphers. And from then on, they knew more about Tukhachevsky than he knew about himself.

They knew when the enemy was planning an offensive, where his headquarters were, and the disposition of the armies of Tukhachevsky, Budyonny, and Yegorov. When, on August 12, 1920, just before the Battle of Warsaw, Kowalewski cracked a new cipher coded "Revolution," the tide of the war turned. Within three hours of receiving it, Kowalewski and Mazurkiewicz deciphered the Russian message. Kowalewski immediately called the Belweder Palace and dictated it to Piłsudski in Russian (without delay for translation or paper circulation).

For his achievements, Piłsudski awarded him the Silver Cross of Virtuti Militari in 1921 – the highest order that could be awarded to a man who had never fired a shot. Some historians would later say that the Poles had won the battle for the future of Europe. General Władysław Sikorski himself, presenting Kowalewski with the Virtuti Militari, is reported to have said:

“For winning the war, Lieutenant.”

Secret Weapon: Mathematicians and Antennas

From 1919 to 1924, Kowalewski was the organizer and head of the Second Radio Intelligence Department of the Cipher Bureau of the Second Division of the General Staff. He was the de facto creator and architect of the entire analytical division of the Polish Army intelligence service.

He possessed a gift that cannot be taught – the ability to connect worlds. Scientists with the front, theory with practice, young mathematicians with stern officers. He built not only a listening network but also a method of operation: reports intercepted in the field were sent directly to analysts, not through slow bureaucratic channels. He read not only front-line reports; he also received political and diplomatic ciphertexts – the map of the war was more complete than ever.

Thanks to him, what we would now call the first analytical center of the Second Polish Republic was created —a combination of radio data, battlefield information, and statistical analysis. In an era when the computer was still a science fiction concept, Kowalewski built a war algorithm.

The mathematical elite was joined by linguists (Słoński, Szachno-Romanowicz) and scout-officers (Plezia, Ciężki, Suryn) – a mixture from which the Polish model of hybrid attack on ciphers was born.

The Silesian Trail and the Japanese Course

After the victory over the Bolsheviks, Poland fought again—this time over its borders. His knowledge was immediately put to use in another "information war"—this time over Silesia.

In 1921, Kowalewski headed the intelligence service of the Third Silesian Uprising. As head of the intelligence staff of the insurgent forces, he made a significant contribution to planning operations and locating German units through radio surveillance. He organized the interception of German communications, predicted troop movements, and warned of impending attacks.

His work was not glamorous, but effective – the “Czapla” intelligence service, as his section was called, allowed Poland to maintain strategic positions and later strengthened the Polish position in international negotiations.

Two years later, in 1923, Poland sent Kowalewski to Japan. There, he led a three-month cryptographic training course for Japanese intelligence officers, making him one of the first Polish experts to export technical knowledge to the Far East. There, in Tokyo, he trained Japanese radio intelligence officers in... breaking Soviet ciphers.

By then, he was something of an ambassador for the Polish school of strategic thinking. Japan recognized his expertise, awarding him the Order of the Rising Sun as the de facto founder of the Japanese Cipher Bureau and radio intelligence.

Although he did not collaborate with the later Enigma breakers, he was their spiritual ancestor.

A Scholar in Uniform

Between 1925 and 1927, Kowalewski studied at the renowned École Supérieure de Guerre in Paris – the cradle of modern military art. There, he honed his skills, which later made him one of the most versatile officers of the Second Polish Republic.

He was no longer just a cryptanalyst, but also a diplomat, strategist, and political analyst. He understood that information warfare doesn't end at the front—it also continues in offices, salons, the press, and in the public sphere.

Moscow: the Art of the "White Intelligence"

In 1929, he became a military attaché in Moscow—a nearly impossible task. The USSR was then a tightly closed country, and its army was shrouded in secrecy. Yet Kowalewski found a way here, too.

From seemingly trivial sources—military parades, newspapers, economic reports— he reconstructed the structure of the Red Army. He could draw from memory the silhouettes of tanks and planes that he had seen for only a few seconds in Red Square. His work in Moscow included, among other things, obtaining a copy of the trade agreement between the USSR and fascist Italy (an important economic document, described by R. Parafianowicz).

Thanks to his reports, Polish intelligence had more accurate data on Stalin's army than most Western countries. But this success came at a price – in 1933, on Stalin's own orders, he was declared persona non grata– likely because the Soviets had intercepted some of his intelligence correspondence following their recruitment of Captain Władysław Borakowski. Even a brilliant analyst couldn't protect himself from internal betrayal.

He returned to Poland, enriched with invaluable experience and the awareness that the Soviet Union does not forget.

Bucharest and the Disillusionment with Politics

From Moscow he went to Bucharest, where as a military attaché (1933–1937) he built a Polish-Romanian alliance – the same one that was supposed to guarantee security in the southeast.

In Romania, he met the elites, observed the corruption, fears, and dreams of a country stretched between Germany and the USSR. He was a realist – he knew that paper alliances wouldn't stop tanks. But he never stopped believing in the power of reason and information. He maintained intense relations with the Romanian elites even after 1937, when he returned home to Poland. Much later, in 1940, he participated in the evacuation of former King Carol II of Romania from Spain to Portugal.

After returning to Poland, he entered politics, co-founding the Camp of National Unity (Obóz Zjednoczenia Narodowego, OZN), serving as OZN's chief of staff, attempting to reconcile the Sanation party with the opposition. He spoke with Mieczysław Niedziałkowski of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) and Maciej Rataj of the People's Party (Stronnictwo Ludowe). He believed that Poland must be united against the coming storm.

When Adam Koc's faction won in 1937, Kowalewski left. He became involved in the war industry, heading the Raw Materials Import Association (Towarzystwo Importu Surowców, TISSA) , which purchased strategic metals for the army. He was not only an intelligence officer and cryptologist, but also an active organizer of the economic base for the country's defense. He already saw that war was inevitable.

"A New Kind of War"

In September 1939, as Poland burned, Kowalewski made his way to Romania. Instead of fleeing to London, he stayed to help. He organized the Polish Committee for Refugee Aid in Bucharest. He saved people, organized transports, and intervened with the authorities.

In November 1939, he even met with the German ambassador to Romania, Wilhelm Fabricius. Not to discuss surrender, but to ask for humanitarian gestures: family reunification, the sending of books and letters. The Germans interpreted this as a probe. Kowalewski interpreted it as a moral obligation.

But he soon realized that a war was coming, the likes of which the world had never seen before – an information war in which victory depended not only on the army, but on the ability to predict, disinformation capability, and influence.

Continued in Part II: "Jan Kowalewski – the Spy Who Wanted to Shorten the War."