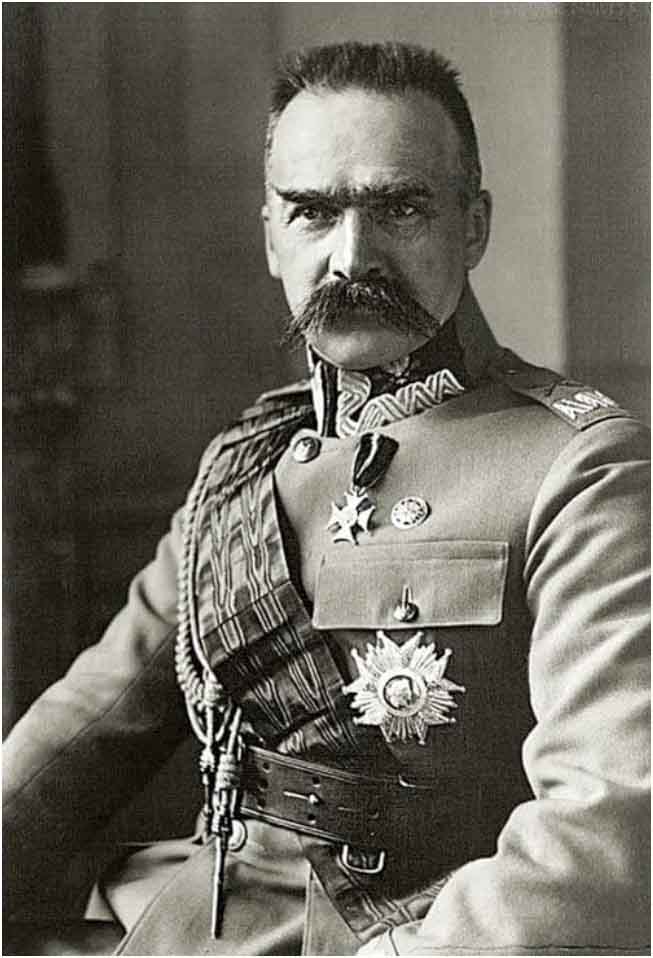

Every city in Poland has a street or square named after him. In Warsaw alone, two bronze monuments commemorate him, though I admit the most impressive are the monumental ones depicting the Chief on a horse, as in Katowice, Nysa, Kielce, and Rzeszów. He remains one of the most important historical figures in school textbooks. He has his own new museum in Sulejówek. His Cadillac, displayed in a display case near Belweder Palace, is admired by crowds of strollers in Warsaw's Łazienki Park every Sunday. It's also difficult to count how many schools and public buildings he patronized across the country. It's safe to say that, nearly ninety years after his death, Józef Piłsudski remains present in contemporary Poland.

Yet, each successive Independence Day celebration on November 11th reinforces my belief that Józef Piłsudski is a significant absentee in the Third Polish Republic today. There are also reasons why contemporary Poles are reluctant to confront the true phenomenon of the Chief.

The main mass event of November 11th, the Independence March, was completely dominated by groups very distant from Piłsudski's political tradition and core ideas. Yet neither in contemporary Polish culture nor in scholarship do we find many examples of serious attempts at a lively and profound reflection on the Marshal's legacy from the perspective of contemporary Poland. It's as if Poles were satisfied with a mute Piłsudski, cast in bronze and placed in the main squares of their cities, rather than as one of the key figures in their 20th-century history, one who still has something important to say to them.

There are, of course, a few good historical books, classics like Cat-Mackiewicz's and Andrzej Garlicki's, as well as a few brand new ones, that help decipher the Piłsudski phenomenon, and they're always worth reaching for. But in recent years, perhaps the only one who has attempted a comprehensive understanding of Piłsudski's overall point with Poland, and what it means for us today, has been Bohdan Urbankowski with his book Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist. It's best to forget about recent film attempts to "revive" Piłsudski as an embarrassing example of intellectual embarrassment and ignorance in contemporary Polish popular culture. This area is practically empty, with perhaps the only notable exception, which we owe to Wojciech Tomczyk and his play "Marszałek" (The Marshal), performed at the Television Theatre by Krzysztof Lang.

This striking absence of Piłsudski from contemporary Polish political reflection and culture is perfectly illustrated by a conversation with Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz, which I once witnessed. When asked directly why Rymkiewicz had never addressed the great subject of Piłsudski in any of his books on Poland, even though he constantly returns to such issues as power, violence, struggle, self-determination, and the drama of modern Polish culture and history, the poet from Milanówek gave a completely evasive answer, and it was clear that the question was deeply distasteful to him. So what is it about Piłsudski that makes us no longer want to listen to him, or even consider what he has to say about us? Why do we prefer him in the role of a monumental, silent absentee?

It's possible that for many raised in the distinctively liberal culture of the Third Polish Republic, Piłsudski, associated with events such as the May Coup, the Brest Trial, or the mysterious disappearance of General Zagórski, is simply too troubling and burdened with accusations of dictatorial and authoritarian tendencies. But is this the real reason why Piłsudski has become a significant absentee in Poland today?

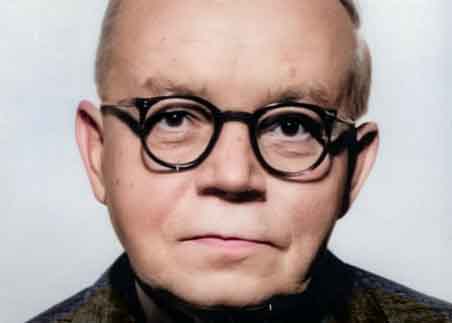

Józef Piłsudski, portrait (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

There is a unique paradox in his silence, for rarely in history have we had such an influential politician of such stature who was simultaneously capable of writing about Polish identity and history with such daring style and insight. Piłsudski left behind a substantial legacy of texts and speeches that constitute an invaluable source of reflection on Polish culture and politics in the 19th and 20th centuries. Suffice it to mention two examples: the text of his speech at Wawel Castle on the occasion of the return of Juliusz Słowacki's ashes to Poland, and his famous farewell speech delivered in 1923 in Warsaw's Bristol Hotel in the Malinowa Room. The latter text should be considered a key expression of the Marshal's views on the attitude of Poles towards politics and their own state. And these were not flattering views.

Although perhaps not entirely unflattering, Piłsudski nonetheless acknowledges that the creation of the Second Polish Republic was made possible primarily by the Poles' ability to unite at a unique historical moment. And this unification allowed for the establishment of a new government, led by Piłsudski, capable of defending and consolidating the new state. At a crucial moment, Poles were able to understand the true nature of power in politics and utilize it to their common advantage. According to Piłsudski, this was the result of moral maturity and overcoming their own weaknesses, a short-lived outcome. The fundamental problem Poles face in their relationship to politics and the state is their inability to maintain their own power. They are weak, soft, divided, and above all—and this is perhaps the most serious accusation—corrupted by decades of cultural, political, and economic depravity to which they were subjected during the partitions. It is this internal weakness and corruption that makes Poles, even if they are capable of momentary unity, fundamentally incapable of using force in politics and statecraft to their own advantage. They are soft and blunt on the outside, yet ruthless and cruel to themselves.

We know what practical conclusions Piłsudski himself drew from this knowledge, especially in May 1926. We can continue to criticize them or attempt to explain them away. That's not the point. What matters is the diagnosis itself, its main message highly unfavorable and disturbing. That's why it's so reluctantly acknowledged, even today.

Piłsudski is the one to whom we owe the founding of the Second Polish Republic. However, his approach to force and violence in politics was both exceptionally un-Polish and modern. This has always made him indispensable and obvious to the public, yet at the same time alien. And so it remains. Therefore, today, we once again celebrate our Independence Day with Piłsudski as our great absentee.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.