The summer of 1920—in the Eastern Borderlands, village buildings are burning, a fair-haired girl is fleeing from Budyonnovites, when suddenly two planes fly over the horizon. They descend to horsehead height, rifles rattle, the disoriented Bolsheviks flee in panic shouting "Americans!" This is how volunteers from overseas entered the Polish War of Independence—among them Merian Caldwell Cooper, the future co-creator of "King Kong" and then a pilot in the Kościuszko Squadron.

An Oath over Pulaski's Grave

Cooper's story begins much earlier, at the dawn of US nationhood. In 1779, at the Battle of Savannah, the mortally wounded Casimir Pulaski was carried from the field by his friend, an American officer, Colonel John Cooper.

At a symbolic funeral aboard the Wasp, John Cooper swore an oath: if Poland ever again demanded its freedom, he or his descendants would come to its aid. Incredible? And yet, this pledge has endured in family memory for generations.

From Annapolis to the Vistula Front

Born on October 24, 1893, in Jacksonville, Florida, Merian grew up in a city that was rebuilding from ruins after the Great Fire of 1901 and soon became a major center of silent cinema. Although fascinated by films, he first chose a uniform: he enrolled at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, from which he was expelled for promoting the superiority of aviation over the navy. He also chased girls and, above all, insisted that airplanes could sink battleships—heresy for the admiralty of the time.

Merian C. Cooper in Polish Air Force uniform in 1920 (Source: Wikipedia)

During World War I, he became a pilot in the US Army Air Service, flying DH-4 Liberty bombers in France. On September 26, 1918, he was shot down and taken prisoner. An obituary was sent home, while he was hospitalized in Wrocław, where his burnt hands were treated—scars he bore for the rest of his life. In the hospital, he met Polish prisoners of war. Conversations about the fight for independence evoked a family oath. From childhood, Poland had seemed to Merian a mythical land of "born soldiers who waged perpetual war."

From Food Mission to "For Ours and Yours"

After the war, Cooper joined Herbert Hoover's American Relief Administration. He was sent with a food shipment to Lviv, saving Polish children from starvation. "There was no triumph there, only a terrible, unequal struggle," he recalled.

After World War I, Cooper and his former comrade-in-arms, Cedric E. Faunt Le Roy, chanced upon each other in a Parisian café. "After exchanging words, it turned out we both had the same goal: to help the Republic of Poland maintain its independence," Faunt Le Roy recalled. Thus, over a glass of wine in Paris, the idea of the Kosciuszko Squadron was born.

In Paris, he reached General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, then Warsaw, and Józef Piłsudski himself. The commander was initially skeptical ("we don't need mercenaries"), but the argument about Pulaski's debt—"Gen. Pulaski gave his life for my country..."—won him over. Cooper was given the green light to recruit experienced Americans.

Their initiative was entirely voluntary, without formal government support. Yet it gained powerful allies—Rozwadowski and Piłsudski himself. Cooper noted years later: "Piłsudski spoke to us a dozen or so words, without flowery platitudes—simple, soldierly, like a soldier to soldiers."

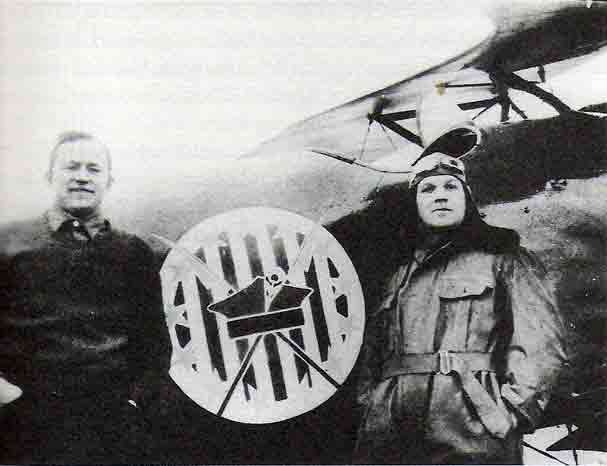

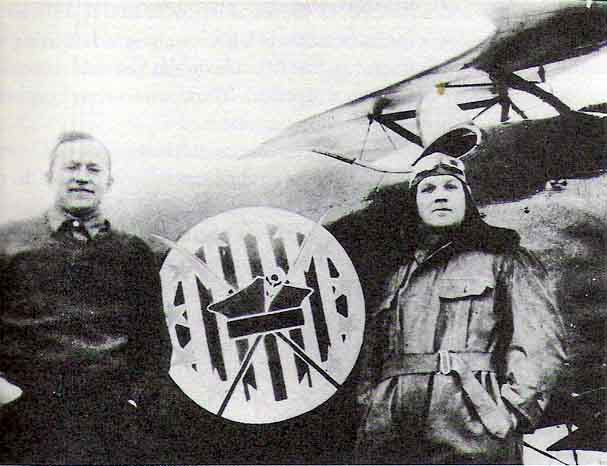

American volunteers, (left-to-right) Merian C. Cooper and Cedric Fauntleroy, pilots of the 7th Fighter Squadron (source: Wikipedia)

Together with Major Cedric Fauntleroy, he assembled a group of pilots who arrived in Poland in mid-September 1919. The Kościuszko Squadron was formed—with an emblem combining the U.S. flag, upright scythes, and the Kościuszko cap. Cooper commanded one of the two groups, named "Pulaski." Fauntleroy wrote of him: "The fiercer the fight, the better he liked it."

Reconnaissance, Bombing and the Legend of 1920

Year 1920. The Russian front swells, Mikhail Tukhachevsky thunders: "Over the corpse of White Poland into the heart of Europe!" In the south, Semyon Budyonny's First Cavalry Army advances. American pilots not only fight and bomb, but above all conduct excellent reconnaissance: it is thanks to their flights, among other things, that Piłsudski's headquarters learns of Budyonny's 30,000-strong army.

The first clash with the Bolsheviks brought the squadron immediate fame. "We descended on the station like hawks," Cooper recalled of the attack on Czudnów.

Not a single shot was fired from the Russian artillery. To our left stretched a long line of wagons; the station was packed with troops. I opened fire with both machine guns and began pounding the wagons.

For Russian soldiers, American planes were something supernatural. Prince Potocki later recalled a prisoner of war who said with horror that "the planes would drop almost to the ground and only then burst with fire, killing dozens." Kościuszko's squadron—a handful of Wild West adventurers—sowing panic among the Red Army ranks.

Cooper's companion, Faunt Le Roy, was renowned not only for his bravado but also for his courage in rescuing others. On May 31, 1920, he warned a train carrying Polish reinforcements of an ambush, halted the train, and then personally led the soldiers in a counterattack. General Listowski then sent a telegram: "American airmen are fighting like madmen. Without them, we'd be lost."

In the field, their presence also had a human face. They flew over rivers where girls were bathing; the girls hid in the bushes "terrified," only to meet the pilots around campfires in the evening. Years later, Cooper recalled this period as the most beautiful of his life.

Shot Down, "Working Hands," and 700-800 km Escape

His luck held—for a while. In June 1920, Cooper and Buck Crawford were shot down, but they managed to escape and return to their unit. On July 13th, however, Cooper was hit again and fell behind enemy lines. Before a Bolshevik "court," he showed his burned hands, claiming he was a conscripted laborer. They believed him—he was sent to a concentration camp.

In the winter of 1921, he escaped with Captain Zalewski and Lieutenant Sokołowski. In knee-deep snow and freezing temperatures, they covered approximately 700–800 km (430-500 miles), mostly on foot, all the way to Latvia. This was his second POW camp in five years, and his second escape.

Virtuti Militari and… American-Style Modesty

For his heroism, Józef Piłsudski awarded him the Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari and other Polish distinctions. Upon receiving the order, he reportedly said: "We felt that we had not failed, that we had served Poland at least a little."

He waived the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross for honorary reasons. He didn't feel he deserved it.

The Legend and the Aftermath

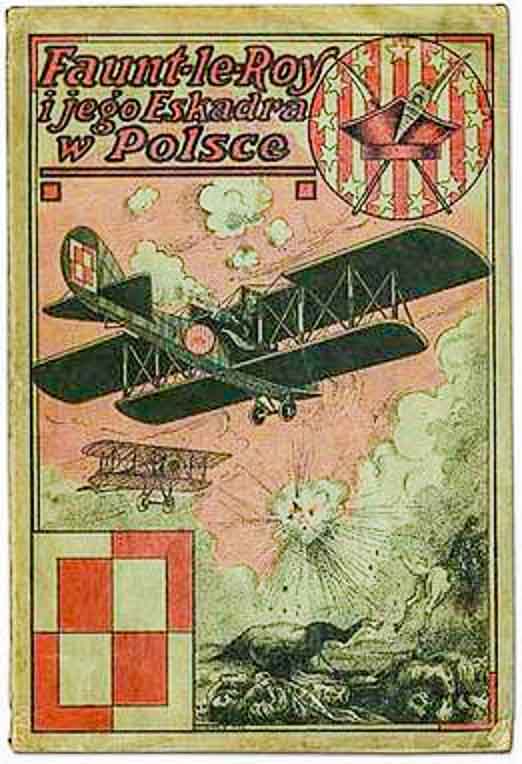

The Kościuszko Squadron became a legend, and 303 Squadron continued its traditions in World War II. In 1922, Cooper published his memoirs in Chicago, "Faunt-le-Roy and His Squadron in Poland: The Story of the Kościuszko Squadron." In 1939, he organized a charity concert for the fighting Polish Republic, visited 303 Squadron (March 14, 1941), and after the war supported Polish airmen in the USA.

Cover of M. Cooper's book from 1922 (Source: Wikipedia)

Poland remembers

Monuments to national pilots stand in Lviv, and ceremonies are held at the Eaglets' Cemetery.

In Warsaw-Bemowo, there has been a Cooper Street since 2008, and in Rzeszów (2018) a roundabout named after him.

His image appeared on the tailplane of the MiG-29, No. 105 (the "Kosynierzy Warszawy" project).

In 1966, the Polish Government-in-Exile awarded him the Gold Cross of Merit with Swords.

In 2010, Marc Cotta Vaz's biography ("The Mad Life of Merian Cooper," WL) was published, and Andrzej Bartkowiak In 2010, Marc Cotta Vaz's biography ("The Mad Life of Merian Cooper," WL) was published, and Andrzej Bartkowiak is preparing a Cooper film.

In the USA, the Foundation to Illuminate America's Heroes, together with Genesis Productions (Bill Ciosek), is developing a film project based on the history of the 7th Squadron; As Ciosek says, the Battle of Warsaw unites Poland and America in a fight "for freedom and glory."

The debt his ancestor incurred over Pulaski's body was more than paid off. Despite his fame, Merian Cooper remained Piłsudski's soldier—a Knight of the Virtuti Militari, a general in the American Air Force, and—as it later turned out—the only veteran of the Polish-Soviet War to receive an Oscar.

We share more of Merian Cooper's colorful life in the next installment, "From 'Grass' to 'King Kong': The Cinematic World of Merian Cooper."