In the second part of the story, we meet a man who foresaw information warfare before the world even learned the word – and who demonstrated that the mind can be stronger than an army.

Part I of this article: "Jan Kowalewski – the Genius Who Won the War... with a Comb"

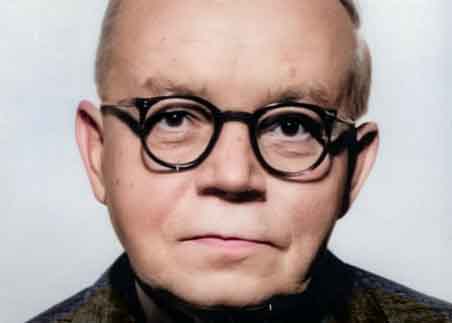

When Poland fell in September 1939 and Europe descended into chaos, Jan Kowalewski—a former cryptanalyst, attaché, and strategist—wasn't looking for a safe haven. His war was just beginning. He knew that the winner wasn't the one with the most tanks, but the one who understood the world better. And in 1940, the world became one giant cipher.

Romania and France – the Beginnings of the Game

After the September Campaign, Kowalewski found himself in Romania, which had become a haven for thousands of Polish refugees. There, in Bucharest, he founded the Central Polish Committee for Refugee Aid – an institution that not only saved lives but also built a network of contacts that would later develop into something much larger.

He was no ordinary bureaucrat. He listened to gossip, analyzed newspapers, and spoke with diplomats. Even in chaos, he could discern the direction of change. He knew that the war for territory was giving way to a war for information.

Eventually, he reached France, where he began work on two memoranda. The first concerned the possibility of an agreement with the USSR, but only if the terms of the Treaty of Riga were maintained. The second, hypothetical talks with Germany, provided they eased repression against Poles.

These were not dreams of an "alliance with the devil," but rather an intellectual exercise: an attempt to find some way to stop Poland from being a passive pawn in someone else's game. Sikorski understood his intentions—and entrusted him with a task that required both courage and genius.

Portugal – "Continental Action"

In 1940, after the fall of France, Kowalewski found himself in Lisbon – a city of spies, conspiracy, and quiet diplomacy. Portugal was neutral, but teeming with agents from all sides. Embassies, intelligence agencies, refugees, and information brokers converged here. It was also here that the "Continental Action" – a Polish project of global significance – was born.

Formally, it was the Continental Communications Post – a small office operating under the aegis of the Polish Ministry of Internal Affairs. In reality, it was the center of Polish continental intelligence, which he directed from 1941 to 1944, organizing a network of contacts encompassing most of the occupied and neutral European capitals.

At the "Ginalda" villa in Monte Estoril, Kowalewski organized a radio communications network, contact points, courier channels, and so-called "fronts": a press office, a foreign trade company, and even a fishing boat to transport people and documents.

The station's monthly budget was a mere $550—yet it generated information that reached the desks of Allied generals. The British Special Operations Executive (SOE) admitted that "no one could exploit the situation in Portugal like Kowalewski."

Europe in a network of spies

In an era when agents were shot for a single slip-up, Kowalewski operated with his visor open – officially as a diplomat, in reality as a coordinator of intelligence operations.

Its goal was to connect the fragmented Europe — the French underground and resistance movements in Belgium, Norway, Italy, and Romania—into a single information network. Continental Action wasn't about blowing up bridges, but about maintaining the bridges over which news flowed.

Poles in Lisbon relayed reports on the mood in occupied Europe, troop movements, and the economic difficulties of the Axis powers. They collaborated with the British, Americans, and French. They were inconspicuous, but invaluable.

Among the participants in the action were officers, scientists, journalists, and even… entrepreneurs who, thanks to legal trade contacts, were able to transport reports in batches of goods.

Kowalewski understood that information must have a cover – preferably a commercial one, because trade never ceases during war.

Player of Three Capitals: Rome, Bucharest, Budapest

The "Continental Action" had an ambitious goal – to break up the Axis Triangle alliance from within.

The Poles tried to persuade Italy, Romania and Hungary – Hitler's satellite countries, still balancing between loyalty and fear – to change sides.

Italy: Kowalewski contacted the anti-fascist opposition, including those around Dino Grandi and Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law. He knew that a rebellion was brewing in Italy, but that it needed a signal that the Allies would not demand unconditional surrender. The signal never came – the decision at the Casablanca Conference (1943) erased any nuances.

In Romania, Kowalewski knew Ion Antonescu—they had met on the slopes of Predeal before the war. Using these old connections, he tried to undermine Romania's cooperation with Germany, stoke defeatism, and encourage contacts with London.

In Hungary, the situation was even more delicate. Regent Miklós Horthy sympathized with Poland and was willing to negotiate with the Allies, but the German occupation in 1944 ended everything.

In each of these countries, Kowalewski quietly played a game for the future of Central Europe. Had the Allies heeded his warnings and invaded the Balkans in 1943, the continent's history might have turned out differently. Instead, Tehran came—and the decision that Central Europe would fall to Stalin.

Meetings with the Devil

Several stories, easily distorted, have survived in the archives. One of them is Kowalewski's meeting with German diplomat Hans Lazar in Madrid in May 1941.

Lazar then warned him that "something big will happen between June 20 and 25." Kowalewski immediately relayed this information to London. This was the first indication of the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union —Operation Barbarossa, which began on June 22.

On another occasion, in 1943, Captain Fritz Kramer of the Abwehr visited him, proposing collaboration against communism. Kowalewski refused without hesitation. "There will be no Polish Quisling" (a Norwegian fascist politician and traitor), he reportedly said.

Rumors about his "contacts with the Germans" persisted for a long time, because in the world of espionage, every contact carries risk. But the documents made it clear: Kowalewski spoke to learn—never to betray.

Attempted Collaboration with the Germans?

In the shadow of war and the hopelessness of 1940–41, Kowalewski became involved in a discussion that still arouses emotions today.

After the defeat of France in 1940, the situation for Polish politicians and military personnel in the West was dire.

General Władysław Sikorski's government was already operating in London, but its position was precarious—many former Piłsudski supporters and Sanacja officers (of which Kowalewski was one) distrusted the Western Allies and believed that Poland must seek a realistic, if morally challenging, agreement with Germany to oppose the Soviet Union.

In Lisbon, Kowalewski co-authored a memorandum advocating collaboration with Germany against the Soviet Union. In the document, he suggested establishing a center in Italy for the study of future Polish statehood—with a formula adapted to the new European order. He justified this by citing the need to counteract pro-Soviet sentiments that, in his opinion, could grip a desperate nation deprived of its own state.

Historians debate whether this was an act of political realism or a moral lapse. Bernard Wiaderny has called it the most serious attempt at Polish collaboration with the Third Reich, while others – like Sławomir Cenckiewicz – see it as more of a "conceptual sketch," an attempt to navigate a world that had temporarily lost its moral compass.

In any case, it was a moment when people like Kowalewski – former vanquishers of Bolshevik ciphers, knowing the Bolsheviks inside and out – felt that the Soviets posed a greater threat than Hitler, and that the West had once again abandoned us.

It's an episode that can't be excused, but it's also difficult to judge from the comfort of time and peace. In a world without certainties, Kowalewski sought one thing: how to protect Poland from communism. Instead of codes, he tried to decipher geopolitics—and it was a code no one has yet fully cracked.

The British Shadow and the Stalin Thread

The British appreciated Kowalewski—for a time. His independence, talent for networking, and broad horizons made him effective, but also... inconvenient.

In 1944, under pressure from the Foreign Office and—not without significance—Stalin himself, who deemed him "dangerous," Kowalewski was recalled from Lisbon. Stalin personally interfered with him twice: in 1933, he ordered his expulsion from Moscow, and in 1944, he pressured him to leave Lisbon. This fulfilled the observation that the Soviet Union never forgets.

Kowalewski received a letter from the British thanking him for his "extremely valuable contribution." Diplomatically, it was written that "his mission had come to an end." In reality, it was the end of an era.

D-Day and the End of the War

Upon arriving in London, Kowalewski assumed the position of head of the Polish Operations Office at Special Forces Headquarters —the headquarters of Allied special units. He coordinated the activities of Polish sabotage groups in France and maintained contact with the resistance movement.

The day after D-Day, on June 7, 1944, his men delivered a report from Normandy: "Polish troops and the French resistance are operating together." Kowalewski knew the war was won. But he also knew Poland would lose the peace.

Life After the Turmoil of the War

After the war, he did not return to Poland. He knew that in communist Poland, he would face no decorations, but a prison sentence. He settled in London. There, he wrote, analyzed, and published. In 1950, he founded the monthly East Europe and Soviet Russia, one of the first Western journals on Soviet studies.

He also collaborated with Radio Free Europe, although his broadcasts have not survived.

Within Polish émigré circles, he was considered a modest and brilliant man, somewhat melancholic, who continued to solve ciphers... this time historical ones. Fascinated by ancient Polish cryptograms, he deciphered, among others, the codes used by Romuald Traugutt during the January Uprising of 1863.

However, he remained on the margins of political life in exile, focusing on analytical and research work, which is worth emphasizing as a consequence of his nature – a man of action who did not like empty debates.

He never stopped believing in the power of intellect. Once, when asked about his wartime experiences, he said:

"Cyphers change. People don't. The hardest code is always the human."

He died on October 31, 1965, exactly 60 years ago, in London, after a long illness.

The man who taught Poland to think with information

Jan Kowalewski was one of those Poles who defies the simple cliché of the gun-toting hero. His weapon was his mind, his battlefield – information, his victory – time bought for Poland.

Before Rejewski, Różycki, and Zygalski cracked Enigma, he laid the foundation—a school of thought where mathematics and linguistics meet patriotism. Before the world began talking about "information warfare," Kowalewski understood that information was the currency of the future.

In an age of fake news, disinformation, and cyberwar, his lesson rings surprisingly true:

Whoever controls information controls reality.

In 1920, his team defeated the Bolsheviks not with numbers but with knowledge. In 1940, he tried to save Europe from total collapse—not with the sword, but with thought.

And today his spirit returns in every Polish cryptologist, analyst and scientist who believes that the mind can be as effective as an army.

The Year of Jan Kowalewski and Posthumous Promotion

It is worth adding that only after many decades did Poland officially appreciate the man who "won the war with a comb."

After World War II, Kowalewski's name disappeared. The Polish People's Republic had no need for heroes of the war with Russia. And when August 15th became a holiday again in free Poland, few knew that the Miracle on the Vistula had the face of a Łódź resident with a comb in his hand. Only after 2000, thanks to the research of Professor Grzegorz Nowik, did his name return to history.

The Sejm of the Republic of Poland declared 2020 the Year of Jan Kowalewski, and President Andrzej Duda, at the request of the Minister of National Defence, promoted him posthumously to the rank of Brigadier General.

Epilogue

From the perspective of a century, Jan Kowalewski emerges as the architect of Poland's intellectual superiority. His work in 1920 was worth its weight in gold—or rather, the weight of independence. He transformed a comb and a piece of paper into weapons that saved the country. From notes and newspaper clippings, he created a vision of the world in which Poland—though small—could be a subject, not an object, of history.

Although more than half a century has passed since his death, Jan Kowalewski himself remains a cipher that Poland has yet to fully crack—a man greater than all the legends surrounding him. And perhaps that is precisely why his genius remains relevant: because he reminds us that thought, courage, and knowledge are the best security code for any free state.