The Polish diaspora, numbering over 20 million people, is one of the country's greatest untapped resources. Historically, it played a key role in Poland's fight for independence, in promoting Poland abroad, in providing extensive financial assistance, and in the development of transatlantic relations. Despite this, in recent decades, the topic of the Polish diaspora has gradually faded from public debate. A prime example of this problem was the recent presidential debate, where not a single word was mentioned about the Polish diaspora. The aim of this analysis is to identify the causes of this process and to diagnose the systemic barriers hindering the utilization of the diaspora's potential in state policy.

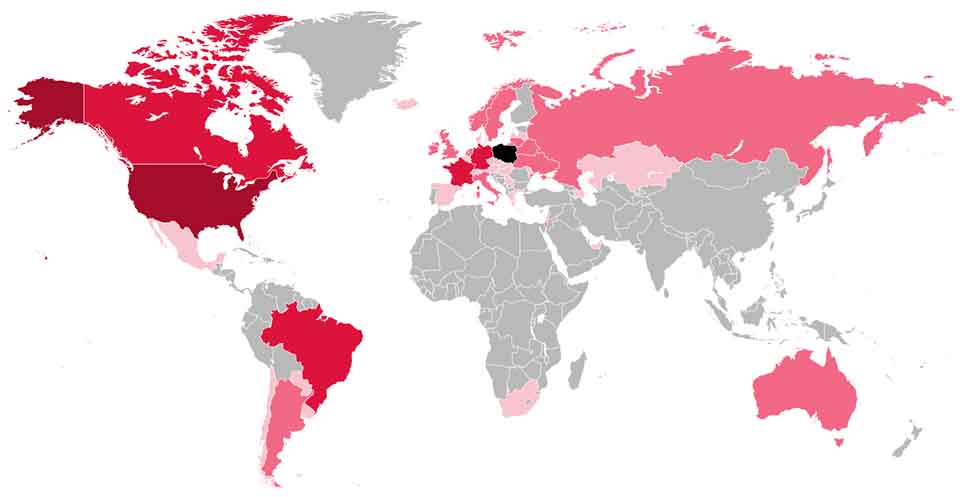

Polish diaspora in the world (Source: Wikipedia)

1. The legacy of transformation and the redefinition of priorities after 1989

After the fall of communism, Polish political elites adopted a Warsaw-centric perspective, focusing on:

- economic reforms,

- building democratic institutions,

- integration with NATO and the EU,

- implementation of the Magdalenka resolutions, which excluded patriotic Polish diaspora from participation in Polish public life.

In this context, the diaspora was deemed less relevant to the state's current challenges. At the same time, central institutions firmly believed that the Polish diaspora's role in the fight against communism had already been "fulfilled" and that its significance could be limited to a cultural and sentimental dimension. This shift in perception initiated a decades-long marginalization of the Polish diaspora's participation in Polish public life.

Magdalenka, the Round Table and their consequences

From the beginning of the Third Polish Republic, the Polish diaspora was excluded from participating in public life. A symbolic example was the failure to invite Ryszard Kaczorowski – the last legal president of Poland in exile – to the Round Table Talks. After 1989, emigration, instead of becoming part of the political lifeblood of a resurgent Poland, was consciously omitted.

As a result, the nation was deeply divided. Post-communist elites "made an agreement" with the communists – as Włodzimierz Czarzasty of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) himself admitted – while patriotic, independence, and émigré circles were sidelined from rebuilding the state. A telling document from the Military Historical Office, dated February 15, 1990, describes a planned meeting between President Kaczorowski and Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki in London. The meeting ultimately failed to materialize – officially for protocol reasons – which only confirmed the marginalization of the émigré community.

President Kaczorowski proposed a meeting with the Prime Minister and the Polish delegation after the meeting with the Polish community in London, provided the ceremonial "entrance of the President of the Republic of Poland" was observed. Mazowiecki refused, considering it an insult to President Jaruzelski and his own government. During the meeting with the Polish community, he was asked: "Why are there still communists in your government, and Jaruzelski is the president of Poland?" He replied curtly: "Thanks to these people, changes have taken place in Poland, and I am the prime minister."

This was a clear declaration of acceptance of the "Magdalenka model"—a compromise with the communists. The consequence of this choice was the lasting division of the nation, the marginalization, and the political blocking of one-third of the Polish nation, the Polish diaspora, the consequences of which are still felt today.

2. Lack of coherent state policy towards the diaspora

Poland still lacks a comprehensive strategy for cooperation with the diaspora. In practice, this means:

- dispersion of responsibility between various institutions,

- lack of strategic goals and measures,

- projects financed ad hoc,

- discontinuity of activities between government terms.

Unlike Ireland, Israel or India, Poland has not built an institutional model that would treat the diaspora as a development partner, capital and diplomatic resource of the state.

3. The instrumental approach of political parties

Political parties in Poland treat their diaspora mainly:

- in the context of elections,

- as a source of potential support,

- as an element of the historical-symbolic narrative.

There is a lack of stable dialogue and cross-party consensus. As a result, the Polish diaspora is perceived not as a partner generating long-term benefits for the state, but as an "additional" group, appearing on the agenda only when politically expedient.

4. Weakening of Diaspora Representation Structures

The most important Polish diaspora organizations, including the Polish American Congress and European structures, are struggling with:

- lack of stable financing,

- aging staff,

- lack of young leaders,

- internal fragmentation.

As a consequence, their ability to:

- lobbying,

- creating its own agenda,

- conducting dialogue with Warsaw on equal terms.

is diminished. The lack of a strong partner on the Polish side means that the topic easily falls out of public debate.

5. Poor coverage of the topic in the national media

Mainstream media focuses on:

- internal conflicts,

- economic issues,

- activities of the government and opposition.

The diaspora doesn't generate rapid political dynamics, isn't a source of spectacular disputes, and its problems require contextual knowledge. As a result, the topic is rarely addressed by editorial offices and remains on the margins of public opinion. Consequently, knowledge about the Polish diaspora is minimal in the media and at important state institutions.

6. The dominance of the Warsaw-centric narrative in the public debate

Following Poland's accession to NATO and the EU, the view has become more established in Poland that the most important political and economic processes take place at the level of the nation state and EU institutions. The role of the diaspora, particularly in:

- civic diplomacy,

- promotion of economic interests,

- building the image of Poland,

- innovation and technology transfer,

has not been incorporated into mainstream strategic thinking. There is a lack of awareness that countries like Ireland and Israel owe part of their success to diaspora capital.

Two historical events also influenced this: President Moskal's position on Poland's accession to the European Union and the senate elections of 2019.

Edward Moskal was the President of the Polish American Congress, who had the courage to express his opinion on Poland's accession process to the European Union. In 2002, he uttered the following words, so important and so true today:

The agreement negotiated in Copenhagen does not adequately protect Polish interests and violates the fundamental principles of the European Union regarding the equality of rights and obligations of all states. We believe that accession entails a far-reaching loss of political sovereignty. Polish parliamentarism and judicial power are at risk. Acts and resolutions of the Sejm and Senate will be devoid of a Polish, national perspective. After joining the EU, Poles will become a nation without their own state.

The second event was the fiasco of the Senate elections in 2019, where an attempt was made to cover up the defeat of the first Polish diaspora candidate, Professor Marek Rudnicki, with an inept narrative about a divided Polish diaspora.

Conclusions

The marginalization of the Polish diaspora topic is the result of:

- lack of political will in Warsaw

- command-and-distribution mode of decision-making between Warsaw and the Polish diaspora

- historical conditions

- lack of strategy and coordination

- weakness of Polish diaspora institutions

- low media exposure

- focus of politics on internal affairs

- disregard for the intellectual, financial, and demographic potential of the Polish diaspora

This doesn't mean, however, that the Polish diaspora has lost its importance. On the contrary, in an era of global challenges, there is a growing need to mobilize Polish communities abroad in the areas of public diplomacy, security, innovation, and the economy. A necessary condition, however, is a new opening in the state's policy towards the diaspora.