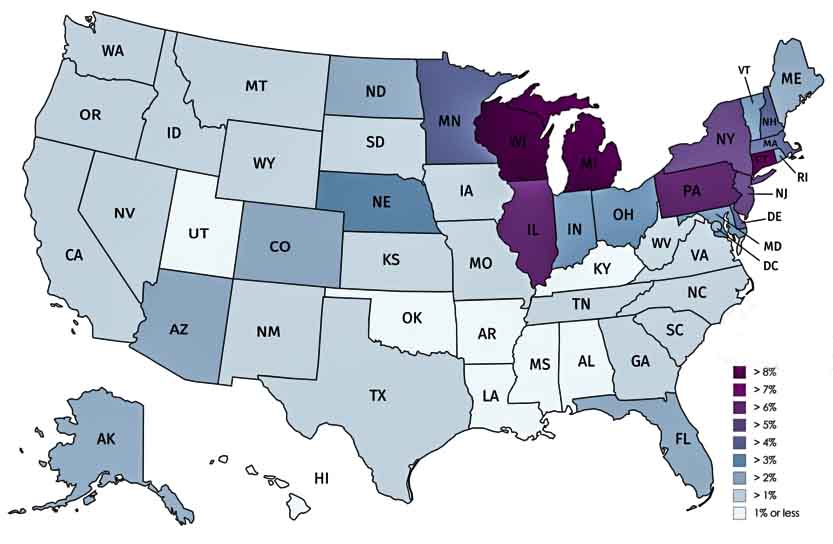

Poles made their presence felt in the United States from the 1830s. They sought refuge on the new continent from persecution for their freedom, or sought bread because the occupying powers had deprived them of the land that provided them with bread and shelter.

From the very beginning, they were involved in the political, social, and economic life of the new country. Kazimierz Pułaski and Tadeusz Kościuszko, among others, left their mark on this country's history, along with those less well-known but no less distinguished, such as Edward Gwardziński, hero of the Battle of Texas, and Wacław Kruszka, author of A History of Poland in America .

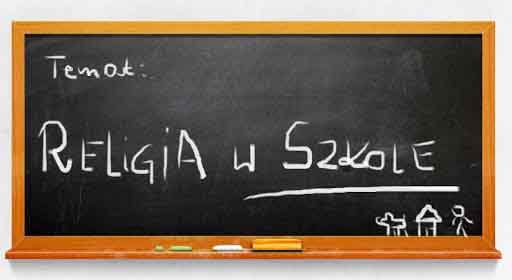

What held Poles together was the Polish language and the Polish churches around which the emigrants gathered. Polish priests were not only clergy but also the true leaders of the Polish community. The growing Polish population built new settlements and grouped around churches. In Milwaukee alone, Polish emigrants built 19 churches, distinguished by their beautiful architecture and the community's social activities. A school was built at each parish church, attended by the children of the Polish community. The schools were bilingual. The children studied and soon became guides for their parents in English-speaking offices and held more prominent social positions.

In their struggle to secure their place in American society, Poles organized themselves into economic and political groups. Learning to read and write in both languages was crucial, both socially and economically. The Polish diaspora placed great importance on educating their children. At the peak of Polish diaspora's growth in the 1920s (1924), the school at St. Adalbert's Church had 1,585 students and employed 23 nuns as teachers.

In subsequent years, the Polish diaspora became increasingly educated and wealthy, but Polish language and culture remained limited to Saturday schools. After Poland joined the European Union, the European labor market opened up, and due to various legal restrictions, emigration to the US was significantly limited and has now almost completely ceased.

According to the latest census, approximately 9.5 million American citizens claim Polish roots, but only about 15% still speak Polish. Schools with Polish as the language of instruction are few and far between, and are found only in large Polish communities, such as Chicago and New York. Education begins in primary school and culminates in a secondary school leaving examination. This opens the door to studies at Polish universities.

At universities in the United States, departments of Polish history, language, and culture are being systematically phased out. The question arises whether Saturday Polish schools make sense and have a future. Perhaps some of these questions will be partially answered in a conversation with teachers and parents of children at the John Paul II Polish Saturday School in Milwaukee, located next to one of the oldest Polish churches, St. Maximilian Kolbe. Throughout its history, the school has experienced various upheavals and disputes over its curriculum, but it has always been faithful to its teaching of patriotic and humanistic values.

The pandemic brutally interrupted its operations and almost completely destroyed its foundation. For over four years, the Polish Saturday school in Milwaukee, the only one in Wisconsin teaching Polish children the ABCs of the Polish language and patriotism during the interwar period and postwar emigration, ceased operations. Its students have gone from children to adults. The question remains: what next? I pose this question to the parents and teachers of the reactivated school.

Polish Saturday School named after John Paul II in Milwaukee (Source: K. Murawska)

Three teachers who work here: Luiza Dudek, Julita Kosiak-Chaltry and Małgorzata Wormsbacher, tell us what learning is like at the school.

Luiza Dudek: Our school community consists of 23 students. The children range in age from 5 to 13. They come from Polish and mixed-race, Polish-American families who have discovered their Polish roots and want to learn about their ancestors. They have family in Poland and want to communicate with their relatives, often their peers, in Polish. Perhaps, knowledge of Polish will open up opportunities for them to study in Poland or another European Union country. Knowledge of Polish can also bring other tangible economic benefits, and our school could be the first step on this path.

Julita Kosiak-Chaltry: We work in three groups: with children who already speak and write well, with a group who speak and understand Polish a little, and with those with no prior knowledge, with whom we treat Polish as a foreign language. Lessons take place in a room next to the same church, now serving as the parish church for Poles and Americans of Polish descent, and the church is now dedicated to Saints Cyril and Methodius. Lessons are held every Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Because our students are still young, the lessons are conducted in a playful way, combining physical activity with intellectual effort. We start with the basics, learning Polish vowels, which are not easy for English-speaking students, but the children enjoy reading from a Polish primer for the first time.

Katarzyna Murawska: Are there many teachers willing to teach at a Polish school? Is learning easy, pleasant and beneficial?

Luiza Dudek: It's not easy, and certainly not for profit. We don't expect any financial benefits. The school is self-financing. Parents pay tuition for the semester. We use this to pay for teaching aids and materials needed for classes. We'd like to do more, for example, organize joint events related to Polish customs, go on sightseeing trips related to the Polish diaspora, or, in the future, take language courses in Poland for the holidays. We dream of friends of the Polish School who would support it financially. We ourselves don't expect financial benefits from working at the Saturday school.

Julita Kosiak-Chaltry: We all teach for the same reason. We want to help raise the next generation of Poles living in America, in Wisconsin, the heirs of such outstanding Polish activists as the brothers Wacław and Michał Kruszków, or great founders and activists of the Polish American Congress, such as Klemens Zabłocki and Karol Rozmiarek, or activists who showcase the richness of Polish culture, such as Ada Dziewanowska, through the dances of the Polish folk group "Syrena." We want to cultivate Polishness through teaching reading and writing, and presenting Polish traditions and customs.

Małgorzata Wormsbacher: I primarily work here because—as a mother of four—I know that cultivating Polish at home, especially in mixed families, isn't enough. The children grow up surrounded by American friends, and speaking Polish is difficult for them. I speak Polish, and they often respond to me in English. Furthermore, they respond to instructions differently at home than at school. Here, they're surrounded by Polish speakers, which energizes them. They also develop friendships and a sense of belonging to a community, which fosters a curiosity about learning more about this community. My group eagerly learns, repeats, and reinforces differences in pronunciation, and we celebrate every sentence we read and every sentence we understand. I believe it's important to continue and develop our Polish language learning.

Luiza Dudek: We would like to have an academy of Polish language and culture for adults, but we would need new teachers and the project needs to be reconsidered.

Other parents share similar opinions about Polish schools. These are young mothers, representing perhaps the third generation of post-war military and "Solidarity" emigrants.

Mrs. Izabela Marzec brings her child to school. She believes it's a good thing that the Polish Saturday school has resumed operations. Regular learning is different than just conversations at home. Furthermore, it's also a way to integrate the Polish community. While waiting for their children, young mothers have the opportunity to talk to each other, exchange experiences about their children, benefit from mutual parenting advice, get to know each other, and even make friends.

The meeting at the John Paul II Saturday School brought a breath of optimism. While we appreciate the efforts made by the teachers, parents, and children, we must thank them all for their efforts and support their endeavors to the best of our ability, for they will bear fruit, perhaps in the near future.

Interviewed by Katarzyna Murawska.