Part 2 of a series of articles on the relationship between the Polish state and its diaspora in the years 1918-1990.

Part 1 can be read here: The Essence of Polonia's Success.

The first part of this text explores the significance and potential of the Polish diaspora, particularly in the United States, where approximately 10–12 million people of Polish descent live. I emphasize its enormous contributions to Poland's rebirth after World War I—military (Haller's Blue Army), political (Paderewski's activities in the US), and financial (major aid campaigns). I also point out that contemporary Polish diaspora is wealthy, well-educated, and loyal to its homeland, yet its economic and intellectual potential remains largely untapped.

I also discussed the historical neglect of the Polish authorities towards the Polish diaspora – from the disbanding of the Blue Army to the Sanationist attempts to subordinate Polish diaspora organizations in the 1930s. I appeal to break with this legacy and recognize the Polish diaspora as a strategic partner in the development of contemporary Poland.

The Polish diaspora, despite being under surveillance by communist services and marginalized after 1989, was and remains the only community consistently defending the Polish raison d'état.

In what follows, I will describe the enormous contribution of the Polish American community to Poland's post-World War II reconstruction and its subsequent political influence. From the post-war aid efforts of the Polish American Council and UNRRA transports worth hundreds of millions of dollars, through lobbying in Washington during the Cold War (Radio Free Europe, the SEED Act, PAEF, support for Solidarity, asylum, and Poland's accession to NATO), to assistance in the natural disasters of the 1990s.

First initiatives – Money and Parcels

Immediately after the war, when Poland lay in ruins, the Polish American community stepped in to help. The first organization to organize a large-scale effort was the Polish American Council. Fundraising efforts allowed it to raise over $5.3 million—a staggering sum for the 1940s. Together with the Polish American Congress, they organized a campaign to send parcels of food, clothing, and medicine, which reached families across the country.

UNRRA – A Wave of American Aid

Even more extensive was the aid organized by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), which began operating in Poland thanks to the efforts of the Polish community in the U.S. Initially, transports went through the port of Constanta, and from September 1945, directly to Gdańsk and Gdynia.

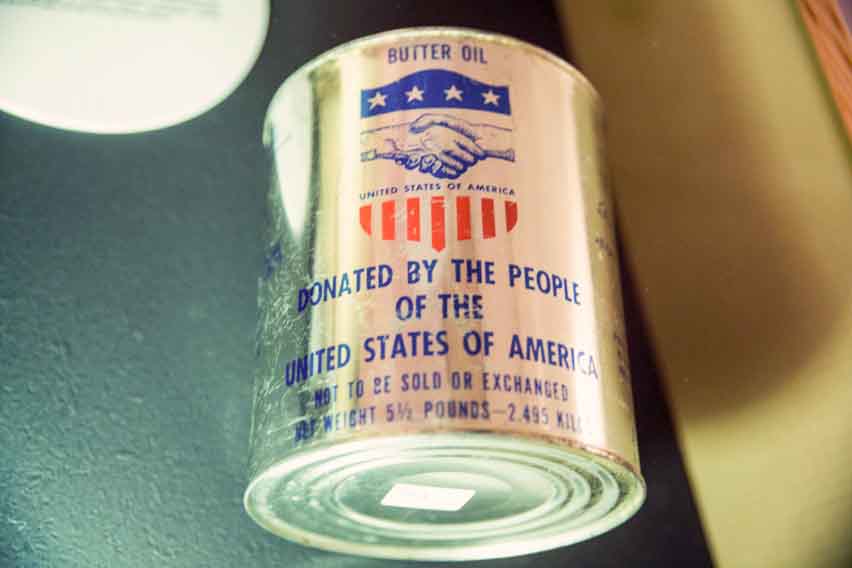

Food can as part of UNRRA aid (Source: Wikipedia)

On September 18, 1945, the American cargo ship Oremar docked at the port of Gdańsk. On board were 1,450 tons of food, over 1,000 tons of soap, 900 tons of used clothing, and 100 tons of new clothing, as well as thousands of tons of tools, machinery, rolling stock, and industrial supplies. Over 500 railcars were needed to transport this single shipment. In the following months, entire ships carrying tractors, trucks, steam locomotives, and agricultural machinery arrived.

The total was impressive: by the end of 1946, 1,812 tractors, 20 steam locomotives, 500 trucks, and hundreds of agricultural machines had been assembled in Poland. In total, the country received approximately 2 million tons of goods from UNRRA—from clothing and medicines, through fuel, to livestock: 140,000 horses and 17,000 cattle. Millions of five-kilogram food parcels came from US military stockpiles. The total value of the aid amounted to $453 million—an astronomical sum at the time.

The failure of General Sikorski's Mission

In March 1941, a Polish recruitment mission arrived in the still welcoming Canada, neighboring the once-again-neutral United States. The recruitment mission for the Polish Armed Forces in the US and Canada took place in 1941-42 and was commissioned by General Władysław Sikorski following his visit to America, where he was enthusiastically welcomed by the Polish diaspora, and who assumed that the recruitment drive would result in an influx of volunteers for the Polish Armed Forces in Great Britain. The mission proved a fiasco. The Polish diaspora learned from the negative experiences of the Blue Army.

Surveillance of the Polish Diaspora after 1945

The patriotic activities of the Polish diaspora were not accepted by the communist authorities. On the contrary, during World War II, Soviet intelligence delegated hundreds of agents to disintegrate the Polish diaspora. Later, the Polish security service took over this primary task. The goal of the Polish and Soviet security services was to completely divide the patriotic Polish diaspora, a state of affairs that persists to this day. However, the role of the communist security service was assumed by other services.

After 1989, no comprehensive monograph on this subject has been written, and observing the activities of the Institute of National Remembrance, one may get the impression that the work of vetting the Polish diaspora will probably not be carried out.

Even though the Polish People's Republic has been gone for over 30 years, many of the people "tasked" with destroying emigration still shine at receptions in Polish diplomatic missions, at parades and religious ceremonies, or even lead Polish parades in the largest cities in America.

The process of demystifying the history of emigration based on the IPN archives, including the so-called restricted collection, remains imperfect to this day. One gets the impression that historians eagerly focus on the immediate post-war years, but avoid, for example, the 1980s, a period crucial to our present day and the building of many careers, including those in emigration. This raises a new question: how many of these secret service agents were recruited into the American services, and why is no one in Poland so keen on vetting the Polish diaspora?

Lobbying of the Polish Diaspora During the Cold War

The Polish diaspora's support went beyond parcels and material aid. At key moments in history, it leveraged its political influence in Washington. Thanks to its actions, the US government:

- financed the activities of Radio Free Europe,

- adopted the Displaced Persons program, enabling 150,000 Poles to emigrate to the USA,

- recognized the Polish borders on the Oder and Neisse,

- conducted an investigation into the Katyn massacre, blaming the Soviets,

- equalized the benefits of Polish veterans with the benefits of American veterans.

Solidarity and the Fall of Communism

In the 1980s, the Polish diaspora's activism was invaluable. Thanks to its lobbying, the US government became involved in funding the democratic underground through the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Other successes included:

- achieving the adoption of the SEED Act – a multi-billion aid program for Poland and other Eastern European countries,

- the creation of the Polish American Enterprise Fund (PAEF) – support for the Polish economy in the transformation period,

- assistance in obtaining asylum for political refugees from Poland under martial law,

- support for immigration amnesty in the USA (for people who arrived before 1979),

- intensive lobbying for Poland's admission to NATO.

Help in the Latest Crises

The Polish diaspora did not turn its back on Poland even in times of peace. In 1997 and 2001, when the country was hit by severe floods, Polish communities organized aid campaigns worth $200 million. They also supported negotiations for compensation for victims of forced labor in the Third Reich.

Looking at the entire 20th century, we see clearly: the Polish American community was not only a source of financial and material aid for Poland, but also an effective lobby in Washington. From UNRRA parcels, through Radio Free Europe and aid for Solidarity, to Poland's admission to NATO, the Polish community demonstrated that it could be a real force in shaping the fate of its homeland.

Polish Raison d'état and the American Polonia

The work of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Jan Smulski – the first Polish millionaire in the USA – activists of the Sokoli Union, Dr. Teofil Starzyński, and volunteers of the Blue Army was continued after World War II by successive generations of Polish emigrants in America. After the betrayal at Yalta and the severance of the state's continuity, the American Polish community – working with the London government – became the only true representative of the Polish national interest in the West.

The first president of the Polish American Congress (PAC), Karol Rozmarek, uttered these historic words:

Defending Poland today is our most sacred and important duty. It is up to us to decide whether this defense will be merely patriotic rhetoric or a true defense, one for which the Polish American community will not have to be ashamed in the future.

These words have never lost their relevance. We are proud of leaders like Rozmarek, Alojzy Mazewski, and hundreds of other patriots dedicated to the Polish cause, who worked for the good of Poland in various corners of the United States.

The Polish American community exerted a significant influence on US policy. This was facilitated by figures of Polish descent and friends of Poland, such as Senator Edmund Muskie, Congressman Klemens Zabłocki, and Zbigniew Brzeziński. It was also thanks to Professor Oskar Halecki, a distinguished historian, that the term "Central-Eastern Europe" appeared in Western terminology.

Another important contribution to building the consciousness of American elites was the work of Professor Kamil Dziewanowski. In 1969, in Milwaukee, he published in English the book Józef Piłsudski: European Federalist, 1918–1922 (Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University), in which he presented the idea of Intermarium.

Among the Polish diaspora's greatest achievements was the initiation of a US Congressional investigation into the Katyn massacre and the recognition of Soviet responsibility. Polonia's influence was also evident in efforts to secure US recognition of the Polish border on the Oder-Neisse River, in funding Radio Free Europe, and in the issuance of a US postage stamp in 1966, featuring a crowned White Eagle with a Catholic cross, commemorating the millennium of the Polish state.

This legacy is complemented by important publications. In 1957, Jerzy Walter published a collection of documents entitled The Armed Action of Polish Emigration in America, and Władysław Zachariasiewicz published The Independence Ethos of American Polonia. Edmund Banasikowski, in his book Na zew Ziemi Wileńskiej (On the Call of the Vilnius Land) (1990), was the first to mention the legendary nurse "Inka" – Danuta Siedzikówna – and introduced the term "Unbreakable Soldiers." For this publication, he received an award from the Association of Polish Writers Abroad in 1989. Professor Donald Pienkoś's book For Your Freedom Through Ours became an emanation of the Pax Polonica idea. In 2008 , Professor Anna Cienciała published the acclaimed Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment in the USA.

This narrative was supplemented by articles by Polish scholars and radio broadcasts on Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. These broadcasts kept alive the memory of Katyn, the Polish Armed Forces in the West, the Home Army, the National Armed Forces, the crimes of the Gulag, the Holocaust, and the treacherous role of Moscow's agents in Poland.

The Polish diaspora also greatly benefited from the work of Edward Moskal, president of the Polish American Congress (PAC/KPA) since 1994. It was he, along with Americans of Polish descent and friends of Poland, who led to the creation of a petition signed by nine million US citizens calling for Poland's admission to NATO.

Magdalenka, the Round Table and their consequences

From the beginning of the Third Polish Republic, the Polish diaspora was excluded from participating in public life. A symbolic example was the failure to invite Ryszard Kaczorowski – the last legal president of Poland in exile – to the Round Table Talks. After 1989, emigration, instead of becoming part of the political lifeblood of a resurgent Poland, was consciously omitted.

As a result, the nation was deeply divided. Post-communist elites "made an agreement" with the communists – as Włodzimierz Czarzasty of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) himself admitted – while patriotic, independence, and émigré circles were sidelined from rebuilding the state. A telling document from the Military Historical Office, dated February 15, 1990, describes a planned meeting between President Kaczorowski and Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki in London. The meeting ultimately failed to materialize – officially for protocol reasons – which only confirmed the marginalization of the émigré community.

Kaczorowski proposed a meeting with the Prime Minister and the Polish delegation after the meeting with the Polish community in London, provided the ceremonial "entrance of the President of the Republic of Poland" was observed. Mazowiecki refused, considering it an insult to President Jaruzelski and his own government. During the meeting with the Polish community, he was asked: "Why are there still communists in your government, and Jaruzelski is the president of Poland?" He replied curtly: "Thanks to these people, changes have taken place in Poland, and I am the prime minister."

This was a clear declaration of acceptance of the "Magdalenka model"—a compromise with the communists. The consequence of this choice was the lasting division of the nation, the marginalization, and the political blocking of the Polish diaspora, the consequences of which are still felt today.