October 12th is an opportunity to remember a person whose contribution to Polish science has not always received the recognition it deserves. On this day in 1953, Czesław Białobrzeski passed away—a theoretical physicist, astrophysicist, and philosopher of science—a man who combined a passion for the exact sciences with a subtle reflection on the nature of knowledge. Today, on the eve of this anniversary, let us attempt to reconstruct his life and legacy so that some of his light may reach Kuryer Polski's contemporary readers .

Childhood and youth in the Borderlands

Czesław Białobrzeski was born on August 31, 1878, in Poshekhonye, in the Yaroslavl Governorate of the Russian Empire, into a family with Polish roots. His father was Teofil, a physician, and his mother was Halina, née Puchalska. Despite the geographical distance from Polish lands, Białobrzeski cultivated an awareness of his Polish heritage from an early age.

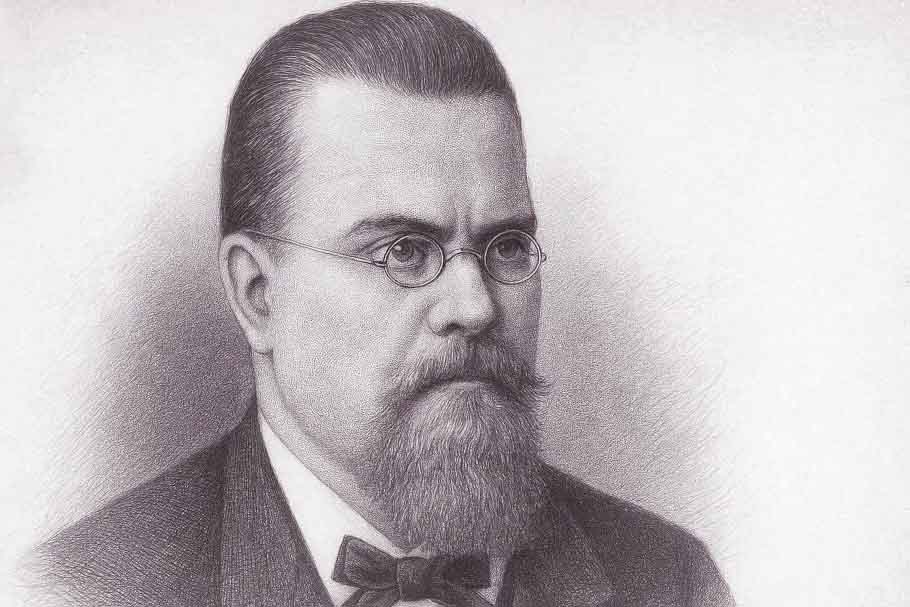

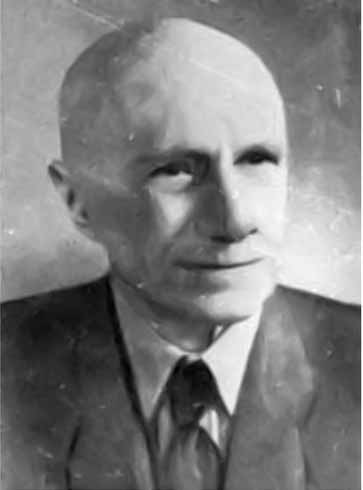

Czesław Białobrzeski (Source: Polish Physical Society)

In 1896, he graduated from the Kiev gymnasium with distinction, which opened the way for him to the local university, where he studied from 1896 to 1901. As a student, he demonstrated excellent mathematical and physical abilities, which later allowed him to continue his education abroad.

He spent the years 1908–1910 in Paris, studying with Paul Langevin at the Collège de France, which gave him direct contact with the European center of new-theory physics. It was there that he developed his awareness as a theoretician, ready to take on the challenges of new physics paradigms.

Kyiv, War, Return to Poland

In 1914, Białobrzeski became a professor at the University of Kiev. There, he pursued research in fields such as spectroscopy, the theory of thermodynamics, the properties of dielectrics, cosmic radiation, and the philosophy of science. It was also in Kiev that he began his reflections on the nature of knowledge and the limits of science, which would later result in important philosophical works.

After the end of World War I and in the crucial year of 1919, Białobrzeski returned to the newly reborn Poland. First, he took up a professorship at the Jagiellonian University (1919–1921), and in 1921 he became a professor at the University of Warsaw, where he worked until the end of his life. In Warsaw, he founded a modern experimental physics laboratory at 3 Oczki Street (1931), equipped with advanced apparatus and equipment for the time.

From 1934 to 1938, he served as president of the Polish Physical Society, co-organizing conferences and developing the physics community in Poland. One of his last significant initiatives before World War II was organizing a conference in Warsaw in 1938 devoted to new physical theories, attended by, among others, Niels Bohr himself.

The War Period - Dramas, Secret Teaching, Reconstruction

The outbreak of World War II cast a shadow over the scientist's life and work. In occupied Warsaw, Białobrzeski transformed his laboratory into a covert facility providing assistance to various city services—using this as a cover for clandestine teaching and continued research despite the dire conditions. Unfortunately, on August 20–21, 1942, the laboratory was destroyed during a Soviet air raid on Warsaw.

The war period was also a time of personal hardship: surrounded by the resistance movement, fighting to preserve the continuity of scientific culture, Białobrzeski often operated under extreme threat. During the dramatic years of occupation, a false report of his execution even surfaced—the information was published in the New York Times, causing a stir in the émigré community. His doctoral student and friend, Myron Mathisson, published a short obituary in the journal Nature in 1940 .

After the war ended, though still very much alive despite the devastation, Białobrzeski did not give up his work. At the University of Warsaw, he took over the Department of Theoretical Physics and began reconstructing his previously destroyed work, including his monumental work, "The Cognitive Foundations of the Physics of the Atomic World." His life in these postwar years was marked by loneliness—although he remained an active scientist, his final years passed in the shadows, far from publicity.

He died suddenly on October 12, 1953, from a heart attack. His remains were buried at the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw, in section 196-1-22.

Scientific Achievements: from Stars to Atoms

While Czesław Białobrzeski's life can be described as a series of challenges and stubborn persistence, his scientific achievements remain a testament to his intellectual strength and versatility. He combined the roles of a rigorous researcher with a philosophical thinker—a rarity among physicists of his time.

Radiation Pressure and Stellar Equilibrium

As early as 1913, he noted the crucial role of radiation pressure in the thermodynamic equilibrium of stars. This approach was innovative—many astrophysicists of the time neglected the influence of radiation in models of stellar structure. Although Białobrzeski's work gained respect in Polish circles, its international significance was partially overshadowed by the later work of Arthur Eddington.

His contributions included analyzing the stability of the gas sphere and demonstrating the influence of radiation on the internal pressure and equilibrium of the star. His work, titled The Equilibrium Thermodynamics of a Free Gaseous Sphere (Sur l’équilibre thermodynamique d’une sphère gazeuse libre), is most often considered Czesław Białobrzeski's most important contribution to theoretical astrophysics and the reason he is called a forerunner of modern stellar models — predating Arthur Eddington.

He discovered that radiation plays a crucial role in maintaining a star's equilibrium. For a sufficiently large mass, the radiation energy (and the resulting pressure) cannot be neglected, as it can even exceed the gas pressure .

He identified the limit of stellar stability. When the radiation pressure contribution to the total pressure exceeds a certain threshold, the system becomes unstable—it can either expand or collapse. This was the first formal description of the condition for stellar stability .

He derived the relationship between the mass, central temperature, and radius of the sphere — what would later become the classical equation of stellar equilibrium (with modifications introduced by Eddington).

He suggested the existence of a natural limit to a star's mass, above which no stable equilibrium could exist (which in later physics led to the concepts of the Chandrasekhar and Eddington limits).

Białobrzeski didn't yet use the term "star" in the strict astrophysical sense—he wrote about a "gas sphere"—but his equations and conclusions precisely correspond to today's models of stellar structure. His research on the gas sphere was also a reflection on the role of abstraction in science — how simple equations can infer the fate of stars billions of years before they are observed.

When Arthur Eddington developed his stellar models in 1916–1926, in which he included radiation pressure, he did not yet know (or did not cite) Białobrzeski's work, although both had arrived at similar results independently.

Thermodynamics, Quantum Theory, Relativity

Białobrzeski authored approximately one hundred scientific papers, covering the areas of thermodynamics, general relativity, quantum mechanics, stellar structure and evolution, spectrography, astrophysics, and philosophy of physics. His articles include The Principle of Relativity and Some of Its Applications, and Reality in the Approach of Natural Science.

He frequently expressed philosophical reflections: he was interested in issues of indeterminism, the nature of natural laws, the limits of knowledge in atomic physics, and the relationship between theory and observation. His work, The Cognitive Foundations of the Physics of the Atomic World (published posthumously), was an attempt to synthesize these reflections.

Role in the Polish Scientific Community

Białobrzeski actively contributed to the development of modern Polish physics. He was one of the first proponents of the theory of relativity in Poland. As president of the Polish Physical Society from 1934 to 1938, he fostered cooperation between centers, promoting conferences, and integrating the community. He was also a member of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences from 1921 and a titular member of the Polish Academy of Sciences from 1952.

Philosophical Perspective

What distinguishes Białobrzeski is his genuine interest in the philosophy of science—not as an adjunct to physics, but as an integral part of it. In works such as Reality in the Perspective of Natural Science, he posed questions about what can be considered real, what "natural science" (i.e., natural science) can say about the world, and what exceeds its remit. He was also influenced by trends in French scientific conventionalism, which influenced his considerations of convention and agreement in scientific theory. Finally, he sought to combine the rigor of physics with a broad humanist culture, a phenomenon that was not obvious in the era of his work.

Difficult Moments, Underestimation, and Remembrance Today

Although Białobrzeski was highly regarded in Polish physics circles, his name—unfortunately—relatively rarely appeared on the international stage as a symbol of a great discoverer. His work on radiation pressure was partially dominated (in terms of citations and publicity) by later studies from the West. Due to the occupation and the devastation of war, his laboratories, notes, and apparatus were repeatedly vandalized, significantly hindering the preservation and promotion of his work.

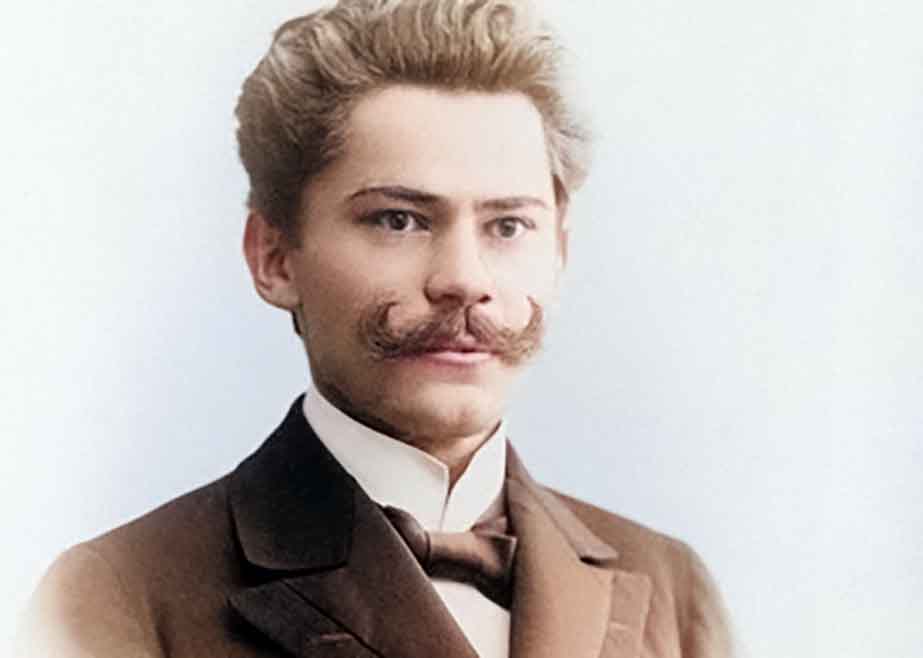

Czesław Białobrzeski (Source: Wikipedia)

However, among historians of science and the philosophy of physics, Białobrzeski is being recalled with increasing frequency today—for example, in articles devoted to Polish natural philosophers in Kiev, and in analyses of the methodology of interwar physics. His archival materials are located in the Polish Academy of Sciences Archives in Warsaw (reference number III-43)—carefully catalogued by researchers.

Scholarly literature has published works devoted to his philosophy, his role in the Polish physical science community, and attempts to reconstruct and interpret his lesser-known texts. He is increasingly recognized as one of those scholars worth recalling to younger generations—as a model for combining physical thought with reflection on science as a cultural phenomenon.

Today - Heritage and Inspiration

For contemporary scientists and students of physics, Białobrzeski's figure can be an inspiration in several respects:

- A combination of science and philosophy – in an era when specialization is often emphasized, he remained a holistic thinker.

- Resistance to historical conditions - both life on the borders of empires and in times of war and reconstruction - did not stop working, despite numerous obstacles.

- Appreciation of opposing voices - in his writings one can find attempts at dialogue with various philosophical trends, which today can be a valuable example of open-mindedness.

- Locality and universality — although most of his work was set in the Polish scientific community, the topics he addressed had and still have a universal dimension: the structure of stars, the nature of knowledge, the limits of science.

From the perspective of 21st-century Poland, we should cherish the memory of such figures — not as hermetic heroes of science, but as people similar to us: with passions, struggles, seeking paths between the light of knowledge and the shadow of uncertainty.

A Reflection on the Anniversary Day

October 12th is the day we commemorate the death of Czesław Białobrzeski—but also an opportunity to reflect on what of his ideas and works remains alive today. In a world of hyper-specialization, rapid publications, and fragmented topics, his life teaches us: it's worth thinking broadly, connecting disciplines, and not being afraid of fundamental questions.

Let us conclude these considerations with words that perhaps Białobrzeski himself would have approved of: that science is not just a tool for describing the world, but a form of dialogue between man and reality – in which sometimes we have to forget about calculation to look at the stars, and sometimes calculate something to understand its operation.

May the memory of the Professor live on not only in plaques and anniversaries, but in the passion of those who continue to "look at the stars."