Jan Szczepanik (June 13, 1872 – April 18, 1926) was a Polish inventor with several hundred patents and over 50 discoveries, many of which are still used today, especially in the film and photography industry and television. Some of his concepts helped in the future evolution of television transmission, such as the telectroscope (a device for reproducing images and sounds at a distance using electric current) or the wireless telegraph, which greatly influenced the development of telecommunications. [Wikipedia]

Jan Szczepanik was born on June 13, 1872 in Rudniki near Mościska in the territory of present-day Ukraine. Already as a student of the Krosno primary school, he showed extraordinary design ideas, where he experimented with toys and machines he built himself. Although he had no problems with learning, in junior high school he had to change schools because he was in danger of repeating the year due to problems with learning Greek. He left Jasło for Kraków and the Teachers' Seminary. After graduating, from 1892, he worked as a physics teacher in rural schools for four years. It was later mentioned that during lessons he was constantly calculating and inventing something, forgetting about the students sitting in the classroom. When he became famous thanks to his inventions, his teaching adventures were described by Mark Twain in the story "The Austrian Edison Keeping School Again".

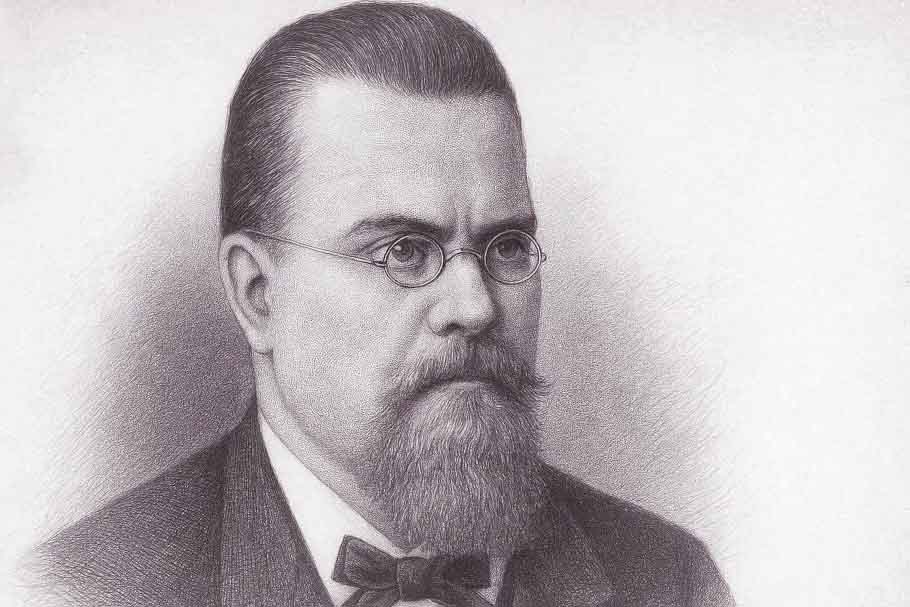

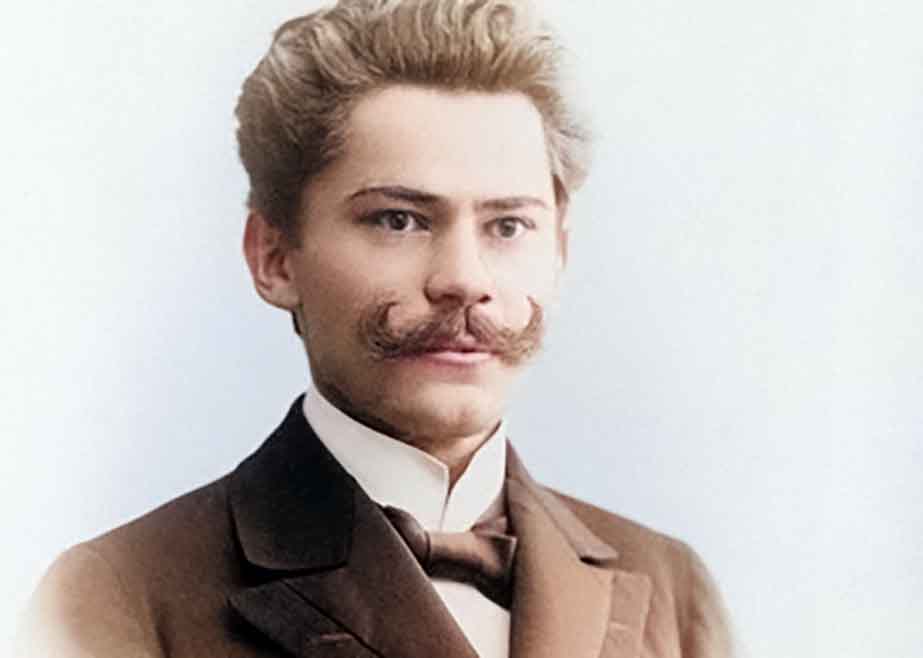

Jan Szczepanik (1872-1926) (Source: Wikipedia)

Szczepanik's first invention was the modernization of the weaving machine. The idea was so well received that it opened the gates of Kraków for him, where he could continue to implement his projects. From there, thanks to Ludwik Kleinberg's patronage, he went to Vienna to create more inventions for the textile industry. In a short time, the following were created: a modern weaving machine, devices for the production of patterns based on electricity and photography, systems for printing multi-colored fabrics and tapestries. It was the tapestry weaving machine in particular that caused a sensation among weavers, and even strikes in Paris, where workers fearing the loss of their jobs in the weaving mills took to the streets. This happened in 1898, when on the machines he had constructed, in a metter of a few hours, Szczepanik made the largest tapestry in the world at that time and presented it to Emperor Franz Joseph on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his reign. The tapestry was 148 cm (58 in) long and 120 cm (47 in) wide.

The inventor gained the greatest fame for the so-called "Szczepanik's armor" — a bulletproof vest designed in 1901 and manufactured on specially designed machines to protect crowned monarchs. When a year later (and several times after that) the Spanish ruler Alfonso XIII escaped death at the hands of an assassin thanks to the armor, its creator was honored with the Order of Isabella the Catholic. He was also exceptionally valued by Tsar Nicholas II, although he did not accept the decoration from him — for patriotic reasons.

Jan Szczepanik is also considered a pioneer of television. Taking advantage of the possibilities of photography and electricity, he constructed a teletroscope – a special device resembling a birdhouse, which transmitted a colored image and sound to a receiver, where it could be viewed. In 1900, the Pole presented his invention at the World's Fair in Paris, calling it a "telephot". The device caused a sensation, it was shown on the cover of the New York Times, and its creator was unquestionably hailed as the "Galician Edison". The life of the Polish inventor became an inspiration for Mark Twain, who wrote two short stories based on it.

In 1901, the Austrian authorities drafted the inventor into the army. He ended up in a fortress in Przemyśl, where he worked on an automatic rifle and a spark telephone. There he met his future wife, Wanda Dzikowska. After the wedding, they initially lived in Vienna, but after the company went bankrupt, the Szczepanik family moved to Tarnów. Thanks to the resources of his wife's family, the designer could continue working on his inventions, primarily in the field of photography. He then invented a color movie camera and a projector.

He worked on improving photography until the end of his life, and his projects were later continued for years by the world's photographic companies. After World War I, Szczepanik divided his commitments between Tarnów and Berlin, where he achieved many successes, including making sound films and recording a surgical operation with a camera. Many of them promised great successes, but were not completed due to his death.

He died on April 18, 1926, due to cancer. He was buried in the Dzikowski family grave at the Old Cemetery in Tarnów. Bogdan and Zbigniew, Szczepanik's sons, continued work on improving the technology of color film production after his death.

Translated from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.