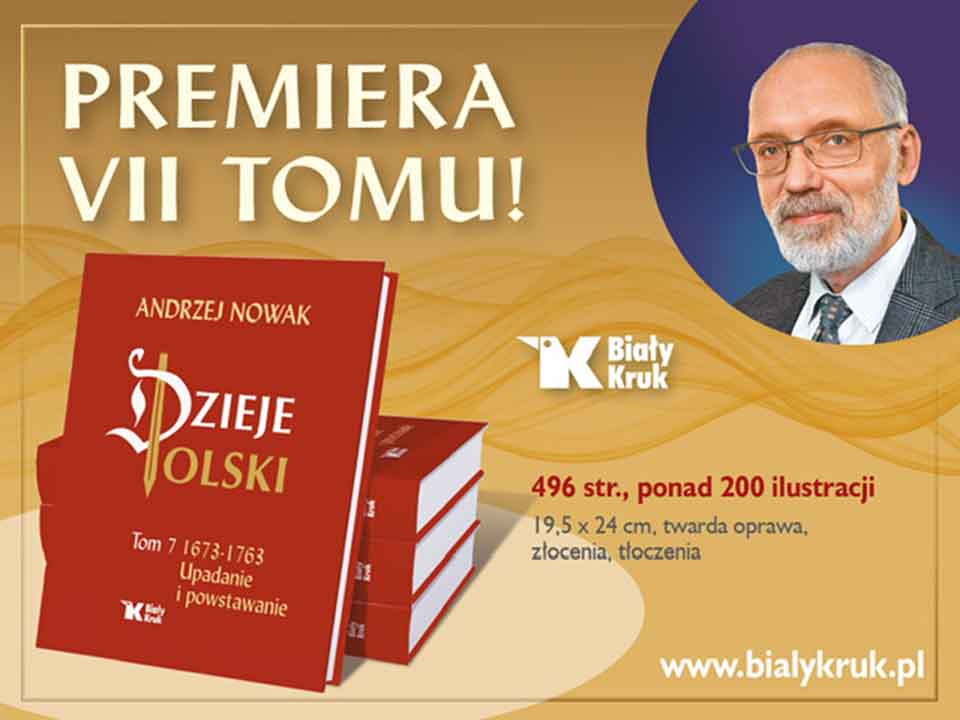

Prof. Andrzej Nowak, who has completed the 7th volume of the monumental "History of Poland" series, in the following recording shares his reflections on the times described in the part titled "Falling and Rising."

As the historian explains, the Polish monarchy had certain systemic flaws that originated before the reign of John III Sobieski or his predecessors: the lifelong tenure of the hetman meant that the person in this position was irremovable, and the powers he had too often led to conflict between the king's power and the hetman's capabilities.

After the Jagiellonian dynasty faded, a free election was devised, with which foreign envoys attempted to interfere; however, they succeeded only at a moment of weakness for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

As I describe in Volume VII, the ultimate symbol of this decline will be the election of 1733, when a majority of citizens, and an overwhelming majority at that—roughly 90% of those who showed up on the electoral field near Warsaw—chosen their candidate, Stanisław Leszczyński. However, the Tsarina, Tsarina, or Empress, if you prefer, Anna Ivanovna, ruler of Russia, together with the ruler of the Habsburg Empire, decided that the king chosen by the Poles was not to their liking; they would choose their own for the Poles. Tsarina Anna sent her troops, which imposed on Poland the ruler Russia wanted, not the one Poles wanted. This was a blatant violation of the principle of free election, and Poland was powerless because it had no army to defend itself against external intervention

explains Prof. Andrew Nowak.

This is where the idea, or rather the popularity of this idea, which will be summarized in the Constitution of May 3rd, came from: let's return to the idea of choosing a dynasty. Some combination of the elective principle, we will make a choice, and citizens will freely decide that this dynasty, and no other, will rule here,

explains the historian, announcing that consideration of this idea will be included in Volume VIII of "History of Poland."

One must certainly respect the argument that after the experiences of the late 17th and 18th centuries, experiences when a free Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and free elections became a fiction, subordinated to the interests of its neighbors, such a measure, such a move, was difficult to challenge, difficult to ignore as a means of repairing the Commonwealth. It was necessary to strengthen central authority and make it long-term independent from the pressure of external empires – this is how one can understand a certain evolution of the idea of elective thrones in Poland. Some believe that the efforts, so consistently undertaken by John III Sobieski until the end of his life, to create his own dynasty, to present his sons as princes who deserved the throne of Poland after him, are a wasted opportunity to save the Commonwealth. Again, I treat such considerations as completely ahistorical, detached from the context, I would say, of the citizens' imagination and political sensitivity, which had to be taken into account,

explains Professor Andrzej Nowak.

As the historian explains, even then, and still today, our national vice was envy, which led the nobility to oppose the reign of John III Sobieski's descendants as part of the new royal dynasty. Hence, the idea of seeking a ruling family abroad was explored.

This is also our trait, a sad one, one that can be grieved over, but a trait that is still so powerful today: we look to foreign countries for someone to come and save us, because we ourselves are incapable of doing anything. A similar mentality began to develop at the end of the 17th century, which I also describe in this volume. I do not approve of it, I criticize it, but it is part of our identity. And it was precisely this attitude that John III Sobieski succumbed to: after all, when he was hetman, he did not seek the throne for himself, as long as some French prince became ruler – that was his attitude. Only Marysieńka, Hetman Sobieski's wife, convinced him: do not seek the throne for a Frenchman, you can become king yourself. This fortunate combination of his wife's pressure and the fact that Sobieski had just won a great triumph at Chocim resulted in him becoming king in 1674. And it was precisely this experience of the mentality of that time, unfortunately still present in our country, that made John III Sobieski's efforts to their sons, especially their firstborn son Jakub, to be heirs to the throne, were considered unacceptable by their fellow citizens and by the magnate factions that led them, who viewed it through the prism of their leaders' ambitions,

says Professor Andrzej Nowak.

The entire statement is available on the Biały Kruk TV channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDPK7Nc_R4c