On March 15, 1000, 1,025 years ago, ended the Congress of Gniezno, which had lasted since March 7. The official reason for organizing this event was the pilgrimage of Emperor Otto III, who ruled the Holy Roman Empire at the time, to the tomb of St. Adalbert, a missionary and martyr murdered by the Prussians three years earlier. Otto met Adalbert during his stay in Rome. This event had a groundbreaking political and religious significance for Poland.

The pilgrimage was an opportunity to meet the Polish prince Bolesław, later called Chrobry, son of Mieszko I and Dobrawa, later king of Poland, crowned in 1025. Mieszko I died in 992, leaving behind four sons and a daughter. Bolesław, born in 967, quickly took power after his deceased father and exiled his (half-)brothers. He began the laborious process of strengthening Poland's position in the realities of Europe at that time.

As a baptized man, born a year after the official baptism of Poland, he was perfectly aware that Christianization protected Polish lands from invasions and provided an opportunity to establish closer contacts with the countries of Western Europe. A good opportunity to strengthen his position arose after the death of Adalbert, bishop of Prague (canonized already in 999). The bishop, expelled from Bohemia, found refuge at the court of Chrobry, and then set off on a Christianization mission to Prussia, where he suffered a martyr's death in 997. At that moment, Poland gained a saint, whose grave ended up in Gniezno.

The official purpose of Otto III's visit was to obtain the remains of Adalbert, bought by Bolesław from the Prussians. It is worth adding that the Polish prince paid for Adalbert's remains in gold in an amount equal to the weight of his body.

The young, barely 20-year-old emperor was also keen, on political grounds, to gain support for his idea of creating a Western universalist empire, composed of provinces ruled by kings. One of them, alongside Gaul, Italy and Germania, was to be Sclavinia (Slavic lands) with Bolesław at its head.

It is interesting to note that Otto III was of partial Slavic descent. His mother was Theophano, a Byzantine princess, but his paternal grandmother was the Czech princess Liutgarda, granddaughter of Wenceslas I – and therefore of Slavic descent. This may have influenced his favorable attitude towards Bolesław.

Otto III was to be accompanied on his journey to Gniezno by a large retinue consisting of German nobles, clergy and knights. This journey was not only a pilgrimage, but also a demonstration of the emperor's power and prestige. Bolesław, in turn, organised a congress on a scale unheard of in Europe at the time – he provided food, accommodation and safety for the imperial retinue numbering hundreds of people. This was not only a polite gesture, but also a political presentation of the young state's capabilities.

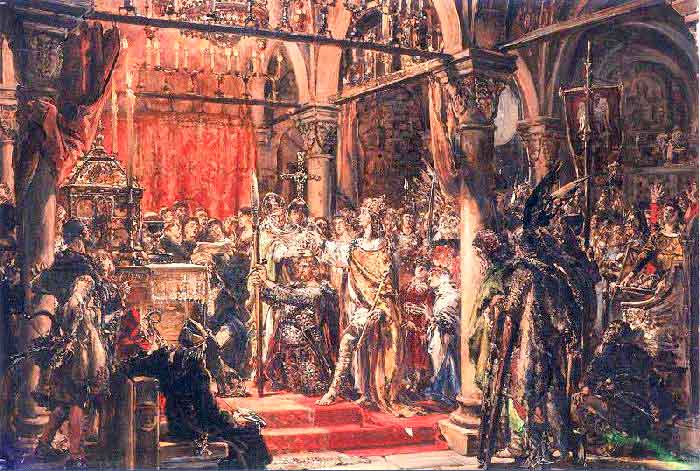

Coronation of the first king of Poland, painting by Jan Matejko (according to the historiography of the time, Bolesław the Brave was crowned by Otto III during the Congress of Gniezno). (Source: Wikipedia)

Otto III dismounted his horse and walked the last part of the journey, barefoot even, as a deliberate gesture of humility. In this way, he imitated the traditions of pilgrimage, but also emphasized the spiritual nature of his visit – and symbolically paid homage to the new saint of the Slavs.

Just before Gniezno, he was greeted by the Bishop of Poznań, Unger. After visiting the saint's tomb, between 7 and 15 March 1000, a series of meetings with the Polish prince took place. During the congress, several symbolic events occurred. Although Brave was not officially crowned during the congress, Otto III symbolically placed the imperial diadem on his head — an unprecedented act, interpreted by some as a foreshadowing of a future coronation.

He also gave him a copy of the spear of St. Maurice. Giving a copy of the holy spear to Bolesław had a huge symbolic meaning – the original was the imperial insignia. Giving this relic was a recognition of his power on an equal footing with other Christian monarchs. Its spearhead has survived to this day and is kept in the Cathedral Museum in Krakow.

In turn, Duke Bolesław gave the emperor the relics of St. Adalbert — his arm — although Otto had likely counted on obtaining the entirety of his remains. It is assumed that the emperor spent the nights in a wooden princely residence specially prepared for him. According to some sources, it was one of the most impressive buildings in Gniezno and was intended to serve a representative function.

The visit also had a diplomatic dimension towards Bohemia. Bohemia, where St. Adalbert came from, was then in the shadow of Poland. The meeting of the emperor with Bolesław (and not with the Czech ruler) emphasized that Poland was the main partner of the empire in the region.

During the talks, the emperor presented Bolesław with his concept of creating an empire, which was favorably received by the Polish prince. Bolesław, in turn, was recognized as a "friend of the empire" ( amicus imperatoris ). This title, granted by Otto III, meant not formal vassalage, but partnership recognition. It was an unusual expression of respect for a ruler from outside the Holy Roman Empire.

The Gniezno Congress also resulted in the decision of Pope Sylvester II to establish the ecclesiastical metropolis of Gniezno (archbishopric), the first on Polish lands to be directly subordinate to the Pope. Radzim Gaudente, brother of the murdered St. Adalbert, was appointed its head. Additionally, new bishoprics were established in Kraków, Kołobrzeg and Wrocław, subordinate to the Gniezno archbishopric. The establishment of the Gniezno archbishopric strengthened Poland's position, giving it real independence through independence from the Magdeburg archdiocese.

It is worth noting that Otto's arrival in Gniezno and his meetings with Bolesław significantly strengthened the position of the Polish prince among the countries neighbouring Poland. Bolesław was keen to receive the emperor with dignity, and offered him, among other things, the relics of St. Adalbert, as well as three hundred armed men – this was not only a symbol of strength, but also real military support that the emperor could use in his campaigns.

As the German bishop Thietmar writes in his Chronicle from the beginning of the 11th century, after the end of the congress, the Brave accompanied the imperial procession to Magdeburg:

It is hard to believe and describe with what magnificence Bolesław received the emperor at that time and how he led him through his country all the way to Gniezno. When Otto saw the desired city from a distance, he approached it barefoot with words of prayer on his lips. The local bishop Unger [bishop of Poznań] received him with great respect and led him into the church, where the emperor, in tears, asked the holy martyr for intercession so that he could obtain the grace of Christ. Then he immediately opened an archbishopric. He entrusted this archbishopric to the brother of the aforementioned martyr, Radzim [...]. After settling all these matters, the emperor received magnificent gifts from Duke Bolesław and among them, what pleased him the most, three hundred armored soldiers. When he was leaving, Bolesław accompanied him with a select escort all the way to Magdeburg, where they solemnly celebrated Palm Sunday [March 24]. [Wikipedia]

The Congress of Gniezno was also recorded by Gallus Anonymus in the Polish Chronicle, who wrote about the splendor and hospitality of the host accompanying the organization of the congress, which aroused the admiration and respect of Emperor Otto III. It was a deliberate diplomatic move, which was intended to build the prestige of the Brave.

Bolesław received him as honorably and sumptuously as befitted a king, a Roman emperor, and a distinguished guest. For for the emperor's arrival he had prepared simply amazing miracles; first troops, various knights, then dignitaries he arranged like choirs, on a vast plain, and the individual, separately standing troops were distinguished by the different colors of their costumes. And these were not cheap gaudy, just any ornaments, but the most expensive things that could be found anywhere in the world [...]. Considering his glory, power, and wealth, the Roman emperor exclaimed in admiration: By the crown of my empire, what I see is greater than the rumor has proclaimed [...]. And having taken the imperial diadem from his head, he placed it on Bolesław's head as a pledge of alliance and friendship [...] and for a triumphal banner he gave him as a gift a nail from the Lord's cross together with the spear of St. Maurice, in exchange for which Bolesław offered him the arm of St. Adalbert. And so great was their friendship that day that the emperor named him brother and collaborator of the empire and called him friend and ally of the Roman nation. [Wikipedia]

Although his account is colorful and often quoted, it should be noted that it was written around 1115 — almost a hundred years later — so that many of the descriptions it contains are more of a propaganda interpretation than an accurate chronicle.

The spear of Saint Maurice given to Bolesław the Brave by Otto III in Gniezno. (Source: Wikipedia)

Unfortunately, good relations with Otto III ended with his premature death, two years after the Congress of Gniezno. Brave had to wait 25 years for the crown, because the power in the empire was taken over by the deceased's cousin Henry II (also called "the Saint"), who was hostile towards Poland, and with whom Brave started wars.

Within the empire, the Congress of Gniezno was criticized by some German elites, who saw Otto as too friendly towards the "barbarian" Slavs. After his death, this policy was abandoned by Henry II, who, although deeply religious (canonized in 1146), was also a ruthless politician who sought to subjugate his neighbors, including Poland.

Bolesław the Brave, who himself began to subjugate the Slavic states previously dependent on the German Empire, in 1002 occupied Lusatia, Milsko and Meissen, and a year later – Bohemia. In 1018 he won an expedition to Kievan Rus and captured Kiev. Henry II demanded a feudal homage from Bohemia, but the Polish prince's refusal became the basis for the German-Polish war.

When Henry II died on 13 July 1024, the main political obstacle to Bolesław's coronation disappeared. In 1025, Bolesław probably obtained the consent of the new Pope John XIX for his coronation, although there is no direct document to this effect.

There is no direct account of the ceremony itself, but historians believe it took place in Gniezno in the spring of 1025, most likely in April or May. Bolesław crowned himself, thus becoming the first king of Poland. This act meant Poland's full independence from the German Empire and Church, and Poland thus entered the group of Christian kingdoms in Europe as a full partner.

Chrobry died—probably of natural causes, perhaps due to age-related illnesses—on June 17, 1025, just a few months after his coronation as King of Poland. He was about 58 years old at the time of his death, which was quite an advanced age by medieval standards. After his death, the throne was assumed by his son Mieszko II Lambert, who also crowned himself king (in 1025).