Exactly five centuries ago, on April 10, 1525, in the very heart of Krakow, an act took place that was not only symbolic, but also strategic. A scene took place there, which in the eyes of those at the time could be considered a symbolic end to the long armed conflict waged by the Kingdom of Poland with the Teutonic Order. Albrecht Hohenzollern, until then the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, knelt before King Sigismund I the Old, symbolically recognizing his supremacy and initiating a new stage in the history of Central Europe.

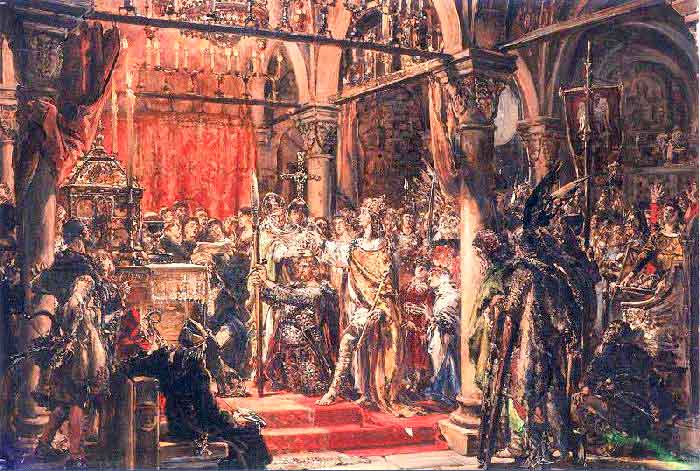

Jan Matejko, The Prussian Homage (Source: Wikipedia)

Despite its theatrical setting – for example, the Teutonic Knights, companions of Albrecht, present at the ceremony, tore off the crosses sewn to their cloaks, demonstrating that they were breaking away from their monastic past – the Prussian Homage was not just a spectacle for the crowds – it was the culmination of a complex political game, played out in the shadow of great European tensions and divisions. From the geopolitical perspective of that era, it was a well-considered and pragmatic decision, dictated by the balance of power in Europe at the time – writes historian Patryk Palka.

16th century realities

When the fighting with the Teutonic Order broke out in 1519, the Commonwealth was in an extremely difficult position. In the east, there was a devastating conflict with Moscow, and from the south, the Ottoman Empire was looking more and more boldly towards Europe. The rulers of the Habsburg dynasty – growing players on the European stage – did not hide their dislike for the Jagiellons, whose influence in Bohemia and Hungary they envied. The south of Europe, in turn, trembled at the threat of Turkish conquest.

In this geopolitical situation, the Pope, concerned about the growing schism in the Church, did not want further conflicts between Christian states to escalate, so instead of supporting Poland, he was inclined to provide diplomatic support to the Order – not wanting to disperse the Christian forces that should have focused on defending themselves against Islam.

The Teutonic Knights, aware of international tensions, sought support from Moscow and the Empire, creating a tight circle of pressure around Poland. The Order did not act in isolation – it built its political base, seeking support from Poland's greatest opponents.

The war dragged on, and neither side managed to tip the scales of victory in their favor. In 1521, a ceasefire was concluded, but neither Poland nor the Teutonic Order could feel like they had won. King Sigismund the Old required the consent of the Sejm [Parliament] and financial support from the nobility to maintain military operations, which, although ready to make sacrifices, was unable to meet the costs of waging war on many fronts. It was the Sejm that decided on taxes, without which waging war was impossible. On the other hand, the Teutonic Order had the support of powerful allies, but was also struggling with an increasingly difficult internal situation. Voices began to emerge in the Teutonic ranks to seek an agreement with the Polish king.

In the meantime, Europe was being shaken by the Reformation – a movement initiated by Martin Luther that was hastening the disintegration of religious unity in Europe. Martin Luther's theses, published just two years before the war, were gaining popularity. The authority of the Pope and the Emperor was waning – the Reformation was weakening their position, and the Order itself began to consider new directions of action.

Under these circumstances, Albert of Hohenzollern, who had taken the head of the order, decided to go to Wittenberg and seek advice from Luther himself. Under the influence of this visit, a plan for radical change matured in him – abandoning the rules of the Order and creating a secular state based on Protestant principles. The prospect of such a turn put him in opposition to his previous patrons – the emperor and the pope – so Albert began to seek new political support. Poland, interested in eliminating the threat from the Order, was a natural partner for talks.

With the end of the armistice approaching, the situation gained momentum. The Habsburgs, although strengthened by the victory at Pavia, were also increasingly involved in the rivalry with France for influence in Western Europe. Poland also had to reckon with new challenges – therefore, a compromise with Albert seemed to be a solution that was not only reasonable, but also necessary.

The culmination of the negotiations was the Treaty of Kraków signed on 8 April 1525, under which the Teutonic Order was dissolved and replaced by a new, secular duchy – Ducal Prussia. Albrecht, as a secular prince, became a vassal of the King of Poland, recognising his supremacy. Poland did not annex these lands, but secured formal control over a territory that had been a source of conflict for three centuries.

Prussian Homage (1796), Marcello Baciarelli (1731–1818). Bacciarelli, somewhat insensitive to historical details, inaccurately depicted the coat of arms of Royal Prussia on the banner – an eagle with a crown and a knight's hand holding a saber. The painter did not place the scene, as Matejko later did, in the Kraków market square, but in an interior with baroque architecture. Although the costumes are not from the period, the artist tried to differentiate them into "Polish", worn by most of the participants of the event, and "foreign", in which he depicted the Teutonic Knights. (Source: Wikipedia)

An essential element of the agreement was the stipulation that the new fief could only be inherited by Albrecht and his brothers and their direct descendants. If this line died out, the duchy was to return to the Crown. This seemed to cut off the Brandenburg line of Hohenzollerns from the succession, but they were to play an important role in the future history of Prussia and Germany.

From the point of view of the Polish raison d'état at the time, this was a wise and far-sighted move, although not everyone agreed with it then. Among them was Queen Bona Sforza, who from the beginning did not like the idea of "arrangements" with the Teutonic Order. The group organized around Primate Jan Łaski and Queen Bona advocated an uncompromising solution — the complete liquidation of the Teutonic state in Prussia and the incorporation of these lands directly into the Crown, which in their opinion was the only way to permanently remove the source of tension.

Sigismund the Old's decision was most likely dictated not by sentiment, but by a cool assessment of the situation. In exchange for abandoning further military operations, Poland gained peace on its northern border, which proved invaluable in the following decades. For over a hundred years, until the Swedish Deluge, Ducal Prussia did not pose a real threat to the Republic.

Only the political mistakes of subsequent rulers, who allowed the Brandenburg line of Hohenzollerns to take over the inheritance, led to the creation of the powerful Prussian state, which played a key role in the partitions of Poland. However, in 1525 no one in Poland could have predicted that the Ducal Prussia would become the seed of a future military and political power, which would unite Germany and become one of the invaders.

So, at the time, the Prussian Homage was a sensible compromise — one that provided Poland with stability and averted the specter of war at a time when threats abounded. It was not the decision to pay homage itself that proved fatal, but the subsequent departures from its original assumptions, says historian Patryk Pałka.

From the perspective of 5 centuries

Looking at the Prussian Homage through the prism of five centuries, it is easy to fall into simplistic judgments and moralizing narratives. However, history, if it has anything to teach us, does not consist in accusing past generations, but in drawing conclusions from their decisions.

In 1525, King Sigismund the Old made the optimal choice under the given circumstances – he avoided further costly war, secured his northern borders, limited the influence of the Habsburgs and gained real control over Prussia.

Only the later loss of vigilance, the consent to the inheritance of the fief by the Brandenburg line of Hohenzollerns, and the surrender of the initiative to the rapidly growing power of Prussia led to disastrous consequences for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. But this mistake was not Sigismund's doing — it was the price for the political shortsightedness of his successors.

The history of the Prussian Homage, although often presented in terms of the triumph of diplomacy over arms, teaches us one thing above all: that every political victory requires not only prudence at the moment of concluding an agreement, but also farsightedness in maintaining it. Decisions made in the name of the state must not only be right at the time of their making, but also consistently implemented by successors. This history, which the Prussian Homage carries with it, is also a reminder that politics — especially international politics — does not know a vacuum and does not forgive omissions.

One might think that the act of homage in 1525 was not a mistake – on the contrary, it was a masterful diplomatic move that defused a long-standing threat without bloodshed. However, the abandonment of this strategy by later decision-makers was to prove tragic in its consequences. On the other hand, from today's perspective, it seems that not secularization, but the complete liquidation of the monastic state and the annexation of Prussia to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would have been a more beneficial solution.

Sigismund the Old operated in conditions of difficult and – as we would say today – multi-vector threats, and his decision was a balanced response to the realities of the era – limited military capabilities, the need to avoid new wars, the tensions of the Reformation, and the changing European alliances.

Today, from the perspective of the 21st century, when Poland is once again in the zone of geostrategic transformations, it is worth recalling those moments in history that showed the power of pragmatism based on a cool analysis of the state interest and drawing conclusions from those events. The Prussian Homage was an attempt to tame chaos through the order of law and feudal dependence — a successful attempt, although its effects were later squandered by the lack of consistency and changing dynastic realities.

Poland has repeatedly found itself at the center of the clash of powers, and its survival has depended on wise alliances, thoughtful calculations, and the ability to balance between the conflicting interests of the big players. For this reason, in an era of renewed shifts in geopolitical tectonics – both in the region and worldwide – the lesson of the Prussian Homage remains relevant: a strong state is not only an army and an economy, but above all the ability to act consistently, far-sightedly, and together in harmony.

In the face of contemporary threats and challenges, the memory of such moments should not only be the subject of academic dissertations, but also an inspiration to build a future based on responsibility for the fate of the state and the nation.