April 10, 2025 marks 500 years since Albert of Hohenzollern, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and the first secular prince of the Prussian state, paid homage to the Polish King Sigismund I the Old.

There would be nothing extraordinary about this, as one of the features of feudalism was the feudal system. It consisted of the liege lord (older, stronger ruler) granting a fief (real estate, usually land) to the vassal in exchange for services rendered. The vassal solemnly paid homage to the liege lord — he knelt before him and swore a solemn oath of allegiance, pledging to help him in council and offering armed assistance if necessary.

To understand the full political complexity and consequences of that historical act, we must go back to the beginnings, development and relations of the state created by the Teutonic Order with the Polish state.

The Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order was founded during the Crusades, in the late 12th century, as an informal association to care for wounded crusaders. In 1191, Pope Clement III officially approved its existence and granted it extensive estates around the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the ancient city and port of Acre, and numerous privileges, thanks to which the order, commonly known as the Teutonic Order from its distinctive symbols (a black cross on a white cloak), was one of the most powerful (economically and politically) orders to emerge in Palestine.

The Order's possessions located in the territories conquered during the Crusades were not safe, they were not secure, so the Order's superiors, the Grand Masters, offered their services to the rulers of the young European states in exchange for granting them possession of the lands and the possibility of settling there. In this way, they acquired numerous possessions throughout Europe.

In 1211 they were invited by the Hungarian prince of Transylvania, who needed support against the Polovtsians who were invading his province. The Hungarian prince quickly realized that the Teutonic Knights had expansionist goals and were striving to build their own state, and in 1225 he forcibly expelled them from Hungary.

However, a new opportunity appeared for the economically threatened order. In 1226, Konrad Mazowiecki invited them to defend the borders of Mazovia against the pagan Prussian tribes. He leased them the Chełmno and Michałów lands, where they established their base of operations in the conquest of the Prussian and Yotvingian tribes. From that time on, the Polish state would have endless diplomatic problems and numerous armed conflicts with the Teutonic Knights.

Still from the film "Krzyżacy" (1960) directed by Aleksander Ford (Source: YouTube)

The Teutonic Knights did not defend the borders of the Duchy of Mazovia, but in the name of converting to the Christian faith, they conquered pagan tribes and built their own state on their territories. The diplomatic struggle, although conducted very skillfully by Polish lawyers, often victorious, did not bring tangible benefits, because the Teutonic Knights as a religious institution were directly subordinate to the Pope, and were militarily supported by the German Emperor. They often forged documents, the rectification of which took a lot of time, during which the political situation could change.

Between the Teutonic state and the Polish state, frequent, shorter or longer wars broke out, often militarily victorious for Poland, but not always economically and politically exploited. King Władysław Łokietek waged long and arduous battles with the Teutonic Knights.

It seemed that the dispute was finally resolved in 1410 by the Battle of Grunwald, but they, although defeated and weakened, still posed a serious threat to Poland. Only the Thirteen Years' War (1454-1466), initiated and financed by the Prussian nobility and burghers and supported by Casimir IV Jagiellon, brought political and economic solutions. After thirteen years of struggle, both sides, financially exhausted, concluded a peace in Toruń, which was beneficial for Poland. Poland regained access to the Baltic Sea and the Chełmno Land, Michałów Land and Gdańsk Pomerania, lost in 1308-1309.

The eastern part of Prussia (Teutonic Prussia) became a fief of the Polish Crown. This meant that future Grand Masters of the Order had to personally pay homage, swearing loyalty to the King of Poland, his successors and the Kingdom of Poland. The first four homages were accepted by King Casimir IV Jagiellon, the fifth by his successor John Albert. Both had to force some Masters to confirm their fealty obligations, because, citing complicated dependencies on the Papacy and the German Empire, they repeatedly refused to pay homage to the Polish King. This was the case in the years 1477-79 and in the years 1498-1525.

From 1511, the master of the order was Albert of Hohenzollern, privately the king's nephew. Due to the complicated political situation (threat from Moscow), the homage was postponed for five years, but Albert made territorial and financial demands to Poland for the alleged occupation of lands belonging to the order. He secretly communicated with Luther and prepared the secularization of lands belonging to the order and its transformation into a secular principality. This was the direct cause of the war fought in the years 1519-1521, which Sigismund the Old won with difficulty, because in 1521 both financially exhausted states concluded a truce for four years, during which a peace treaty was prepared.

After four years, the political situation for Albrecht was so unfavourable that he decided to make peace and pay homage to the Polish king. The peace treaty was signed on 8 April 1525, and two days later, on 10 April, Albert solemnly swore an oath of allegiance to Sigismund the Old in the market square in Kraków. The king was dressed in coronation robes, which emphasised the exceptional nature of the situation.

The secular prince, kneeling and swearing on the Bible, was accompanied by a delegation of knights who, as a sign of political transformation, tore off the black crosses from their cloaks. Albrecht received a pennant with the coat of arms of Ducal Prussia from the king as a symbol of fief. The sign of dependence on the king and the Crown was symbolised by the letter S (Sigismundus) placed on the chest of the black Prussian eagle and the crown around its neck. Many Polish senators of the time believed that the threat should have been completely eliminated by annexing Prussia to Poland. However, this did not happen.

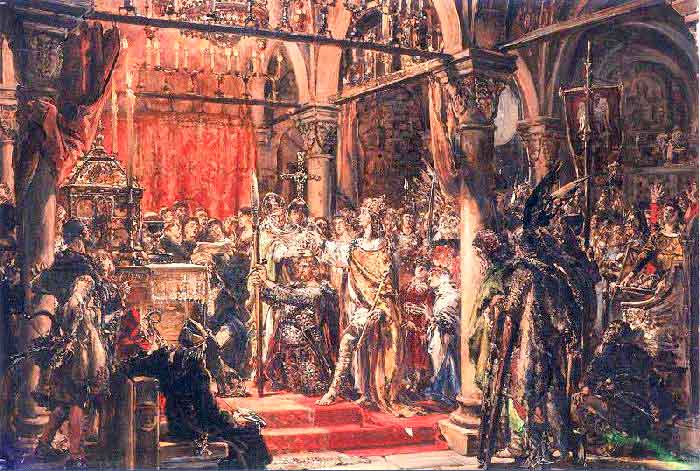

Jan Matejko immortalized this historical moment in his famous painting The Prussian Homage . This event was one of those in Polish history that had a strong impact on its future fate.

Jan Matejko, The Prussian Homage (Source: Wikipedia)

Historians still argue whether the provisions of the Kraków Treaty were a success or a failure for Sigismund the Old. Should the blame for this, for Prussia's later independence from Poland and its participation in the partitions, be placed primarily on Sigismund or solely on his successors? Or perhaps Poland's fall was caused by a number of other, unfavourable historical situations..?

Success or Failure?

The Prussian Homage was, in a way, the final end to the Polish-Teutonic disputes that had been ongoing since the beginning of the 13th century. The peaceful liquidation of the Order put an end to its anti-Polish activities. Additionally, the secularization of the Order meant breaking away from its dependence on the Holy See and the Empire. Secularized Ducal Prussia became a hereditary fief of the Kingdom of Poland but remained in the hands of the Hohenzollerns. The treaty stated that after the extinction of the Hohenzollern line, Prussia would return to Poland, and this situation occurred in 1618. Ducal Prussia could be incorporated into Poland, because that year the last male descendant died, who, according to the provisions of the Treaty of Kraków, could be a hereditary Prussian prince.

However, subsequent kings, especially Sigismund III Vasa, loosened the bonds of fiefdom for short-term benefits. This was also influenced by the aggressive and disloyal attitude of Prussia itself and the pro-Prussian actions of Polish magnates. Nevertheless, until the mid-16th century there was a chance that Prussia would join Poland. However, this did not happen. As a result of the political weakening of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Welawa-Bromberg treaties of 1657, Prussia became independent of Poland, grew in strength and in the following century partitioned Poland.