Who among Poles does not know the dramatic speech on "peace and honour" by Foreign Minister Józef Beck on 5 May 1939, which he delivered in response to Hitler's denunciation of the non-aggression pact? But do we know why there are such extreme opinions about him? Was he a bad minister or rather a victim of a combination of unfavourable international situations? Do we know why his escape attempts from Romania failed? What did General Sikorski have to do with it? How many Poles were victims of Soviet repressions, including in Katyn, Bykivnia, Mednoye? How many of them were Jews? What really happened in Jedwabne? What does the West know about Polish history, how do they interpret it, what is taught about it in schools?

Professor Anna Cienciała, one of the most distinguished Polish historians abroad, sought answers to these and other questions in her academic work. She mainly dealt with the history of 20th-century diplomacy, Poland's place in the politics of the great powers and, in particular, the Free City of Gdańsk, which was close to her. Her most famous works include the books Poland and the Western Powers 1938–1939. A Study in the Interdependence of Eastern and Western Europe and From Versailles to Locarno. Keys to Polish Foreign Policy 1919–25, as well as editions of sources Polish Foreign Policy in the Years 1926–1939. Based on the Texts of Minister Józef Beck, and Katyń. A Crime Without Punishment. The professor linked her professional life with the University of Lawrence, Kansas, in the United States, but before she arrived there, she shared the wartime fate of millions of Poles: wandering and emigration.

Anna Cienciała in 1952 (Source: RB)

Anna Maria Cienciała was born on November 8, 1929 in the Free City of Gdańsk as the daughter of Andrzej Cienciała (1901–1973) and Wanda née Waissmann (1903–1994). Her mother was the daughter of an employee of the Polish Railway Directorate in Gdańsk, Wincenty Waissman, and she graduated from the Polish Gymnasium in the Free City of Gdańsk. Her father came from Cieszyn, Silesia, but decided to "go to the sea" and completed his studies at the Maritime Academy in Tczew. In 1927, he became the director of the Polish Maritime Agency with an office, first, in Gdańsk, and then in Gdynia, and also served as the President of the Shipbrokers' Association, a counselor of the Chamber of Industry and Commerce, a member of the Gdynia Port Council, a commercial judge and honorary consul of Estonia for the Pomeranian Voivodeship. It was because of her father's work that the family moved from Gdańsk to Gdynia.

In the years 1936-1938 Anna Cienciała studied at the Ursuline Sisters' school in Gdynia. After the outbreak of the war, at the end of 1939, thanks to the diplomatic contacts of her father, who - among others thanks to the help of the Estonian ambassador to Poland Hans Markus - had earlier escaped with the Polish government to Romania, the family managed to leave occupied Poland and, after a long journey through Berlin, Budapest and Milan, reached Paris. After the capitulation of France in June 1940, the family left through Spain and Portugal for Great Britain, where they stayed until 1952.

In Great Britain, Anna Cienciała continued her education at the Ursuline School, first in Reading and then in Westgate-on-Sea. In 1947, she passed her matriculation exams, winning the first state scholarship for talented youth in the history of the school. She chose to study at the Department of Slavic and East European Studies at the University of London, but it turned out that under the regulations of the time, her father earned too much for her to use the scholarship to study in London, and she was sent by the Ministry of Education to the University of Liverpool. On 4 July 1952, she received a Bachelor of Arts in modern history there, based on the work War and Peace Propaganda 1711–1712. Piers and the Parliament.

In the same year, Anna Cienciała's parents, due to the lack of prospects in Great Britain, decided to leave for Canada, where their younger daughter, Anna's sister, Danuta, was already living with her husband. Anna left with them, but soon moved to New York, where she began studying for a master's degree at the Institute of Russian Studies at Columbia University. For financial reasons, she was forced to abandon it and return to Montreal. She began studies at McGill University, where on October 6, 1955, she received a master's degree in contemporary European history based on a thesis on the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 (The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 in the Light of Polish–Soviet Relations During World War II).

Anna Cienciała – the first female scientist at the Department of History at Kansas State University – 1965 (Source: RB)

After completing her studies, she returned to the United States, having been offered an assistantship at the University of Indiana in Bloomington, where she worked from 1956 to 1960 and where she began her doctoral studies. However, she did not end her contacts with Canada - as a lecturer at the Université d'Ottawa and the University of Toronto, she taught classes on the history of Central and Eastern Europe and the history of Russia and the USSR, among others.

In 1962, she earned a Ph.D. in contemporary European history from the University of Indiana in Bloomington, specializing in the history of Eastern Europe. Her dissertation focused on the analysis of Poland's political relations with the Western powers in the interwar period, working under the supervision of Professor Piotr Wandycz. Her doctoral thesis was published in 1968 under the title Poland and the Western Powers 1938-1939. A Study in the Interdependence of Eastern and Western Europe. The book received the Józef Piłsudski Institute of America Award.

After defending her doctorate, A. Cienciała planned to stay in Toronto, but in the fall of 1964 the head of the history department invited her for an interview and said: "Unfortunately, I have to tell you that your doctoral thesis is not at the level required here in Toronto", making her understand that she could not count on continuing her employment, so she began looking for another position.

At the State University in Lawrence, Kansas, a center for Russian and Eastern European studies was developing, which she was informed about by a colleague, Dr. Jarosław Piekałkiewicz, whom she knew from Indiana. He was a professor of political science in Kansas and gave them her name. The department authorities invited her for an interview and as a result of winning the competition, she received the position. A. Cienciała left Canada in September 1965 and settled in the United States permanently. She obtained an immigration visa from the pool of the Free City of Gdańsk. She received American citizenship in 1970.

Anna Cienciała in the 1980s (Source: RB)

She worked as a researcher and teacher at the University of Kansas in Lawrence for her entire professional life. First, from 1965 to 1971, she was an assistant professor, and in 1971 she received the title of professor. She retired in 2002. She died in 2014 in a hospital in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, at the age of 85.

Professor Cienciała's legacy came to the IPN in October 2015 thanks to Rafał Stobiecki, professor of history at the University of Lodz (author of, among others, the book Klio za wielką wodą. Polscy historycy w Stanach Zjednoczonych po 1945 r., published by IPN, Warsaw 2017), who suggested to Ms. Romana Boniecka, the sole administrator of the legacy and Professor Cienciała's best friend, that it be transferred to the IPN. In September 2015, two IPN employees went to Lawrence to take over her legacy on behalf of the IPN archives.

There is a funny story connected with the transport of these materials to Poland. Namely, the aforementioned professor Stobiecki, who was on a reconnaissance trip to professor Cienciała's house, estimated the size of the legacy at "several binders", "several dozen folders". With this information, IPN employees came to Kansas to take over the legacy. Appropriately to this volume, they also had the financial resources to cover the costs of transporting it to Poland.

On site, it turned out that the size of the collection was rather several cabinets than binders weighing over 320 kg (705 lbs)! The US Post Office estimated the transport at 5 thousand dollars, the IPN employees had... 500.

A frantic search for a cheaper solution began. And it was found. The Polamer company agreed to transport the entire collection for this amount, but on the condition that the collection would be delivered to Chicago. The state of Kansas is almost a thousand kilometers away from Chicago, and this amount of materials is not something you would carry under your arm. How to do it? And here was the solution: previously unfulfilled doctoral student of professor Cienciała, and later her long-time assistant Judy Glass, took it upon herself to transport 20 large boxes in a rented semi-truck to Chicago. And so they were. From there, Polamer transported them to Poland.

Judy Glass deserves another mention. As mentioned, she planned to write a doctoral dissertation under the supervision of Professor Cienciała, but for personal reasons it was not completed. However, the ladies remained in touch, and over time it turned out that Judy Glass also had other valuable skills. As the professor's scientific materials grew, the question arose of how to store them so that they were easily accessible. At that time, Judy, who had previously worked at a law firm, created an original system for cataloging these materials. They were grouped into thematic groups, e.g. Józef Beck, Katyń, Jedwabne, etc., and within each group there were related materials - source extracts, scientific works by other authors, own and foreign reviews, publications on the subject, materials from the press and the Internet, A. Cienciała's editorial work on books, scientific articles, conference papers, correspondence that Prof. Cienciała conducted with various people. Each issue was a separate folder appropriately titled with a given chronological framework. After an initial inventory of these materials, it turned out that there were almost 2,300 folders - both large and small!

The size of the collection is not only the result of the achievements in the scientific work of Prof. Cienciała, but also the breadth of her interests, the care with which she cultivated her research workshop, her enormous energy, her unquenchable passion throughout her life, and her great diligence. Such a collection is an invaluable help for every researcher of history.

One of the most valuable elements of the collection is the correspondence that Professor Cienciała maintained throughout her life. From her master's studies in Canada until the last period of her life, it was a medium through which the professor conducted polemics and disputes, exchanged historical knowledge with recipients, carried out editorial work, applied for grants and dealt with organizational matters related to participation in conferences, and maintained contacts with friends and family. In later years, mail was replaced by e-mail correspondence.

Professor Cienciała maintained extensive contacts with historians almost all over the world, and among the figures-correspondents close to Poles are Jerzy Giedroyć and Zofia Hertz from the Literary Institute in Paris, Piotr Wandycz, Wacław Jędrzejewicz, Doman Rogoyski, Andrzej Beck (Józef Beck's son), Edward Raczyński, Aleksander Gieysztor, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, Zbigniew Brzeziński, Ted (Thaddeus) Gromada and many others.

She was also connected by long-standing ties with Polish organizations of science and culture, such as the Józef Piłsudski Institute in America, the Kościuszko Foundation, the Literary Institute in Paris or the Polish Institute and the General Sikorski Museum in London, as well as with Polish, American and Canadian organizations. She also visited Poland many times in connection with archival research, at conferences, and visiting family and friends.

During one of these stays, in 1970, she met Mrs. Roma Boniecka, who eventually became her closest friend. The ladies were friends for over 40 years, and Mrs. Boniecka also became the executor of Prof. Cienciała's will and played a key role in transferring her legacy to the IPN.

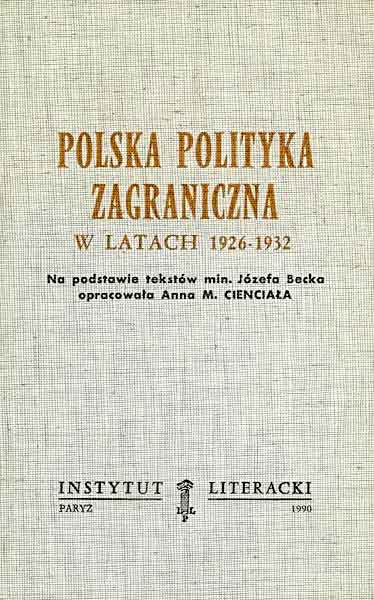

Cover of the book "Polish Foreign Policy in the Years 1926-1932" with an incorrectly printed title - it should be "1926-1939" (Source: RB)

In addition to correspondence, her legacy also includes documentation of editorial work on the professor's books, articles, reviews and conference papers, teaching materials for classes conducted at the university, outlines of lectures and popularizing articles, letters to newspaper editors with corrections or information expanding Americans' historical knowledge of Poland, grant applications for research funding. All mentions of the professor in the media, newspaper clippings with press interviews given, as well as recordings of radio interviews, references to the scientific works of Prof. Cienciała by other researchers have also been collected with exceptional meticulousness.

The professor has been honored and awarded many times for her work over the years, including in her homeland. In 2000, she received the Officer's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, awarded by the President of the Republic of Poland, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, for Polish-American scientific and academic cooperation, and in 2014, posthumously, she was awarded the Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland by President Bronisław Komorowski.

In 1991, she was elected a foreign correspondent member of the Polish Academy of Learning, and in 2012 she received the award of the Association of Polish Writers Abroad for her lifetime achievement and popularization of Polish history. She also achieved success in her adopted homeland, being honored with biographical entries in the compendiums Who's Who in America, Who's Who of American Women, Polish–American Who's Who, University of Kansas Women's Hall of Fame.

The Professor was also an extremely generous person, donating significant amounts of money to sponsor initiatives promoting the history of Poland, such as making a donation to establish the Polish Chair at the University of Virginia.

The period and place of birth, teenage years, life experiences and people she met left their mark on Prof. Cienciała's scientific interests. In particular, her childhood spent in Gdynia and its proximity to the Free City of Gdańsk, as well as the outbreak of the war determined her later scientific work. Seeking an answer to the question "how did it happen?", she focused on research on Polish-German relations and the status of the Free City of Gdańsk, Poland's place in the politics of the great powers and, more broadly, on Polish foreign policy seen from an internal Polish perspective and from the perspective of the "West", broadening her interests to include the history of Eastern Europe, Russia and the USSR.

As a native of Poland, also in the context of the university, she often had to face negative - and in her opinion unfair - opinions about Poland in the "West", especially about its interwar foreign policy, such as Józef Beck's alleged collaboration with the Third Reich (even calling him a German agent), blaming Poland for the outbreak of World War II, equating Piłsudski with Hitler and other accusations. In her works, she tried to dispel persistent stereotypes, demonstrating the groundlessness of the accusations, presenting the motivations of the "Polish raison d'état" and the goals of Polish foreign policy at that time, the choices that Polish politicians faced at that time, their entanglement in a broader international context and the great powers' own policies that shaped their actions towards Poland.

She was also prompted to take up these topics by an event from her first year of studies. As she recalled, "When one of the history professors found out that I was Polish, he attacked me furiously, almost foaming at the mouth, for Poland's policy towards Czechoslovakia in 1938: "How could you! In such a situation!" I was shocked because I knew nothing about it. (...) I swore to myself that I would study it someday. I would find out what it was all about and what were the goals of Polish foreign policy at that time." From these experiences, the source edition Polish Foreign Policy in the Years 1926-1939 was created, based on texts by Minister Józef Beck , as well as articles such as Józef Piłsudski in Anglo-American Information and History Textbooks after World War II. The issue of the negative stereotype-myth, popularization lectures, e.g. The 20th Century Polish History Distorted in University Textbooks, as well as the (unfinished) book The Free City of Gdańsk in the Politics of Great Powers 1918-1939.

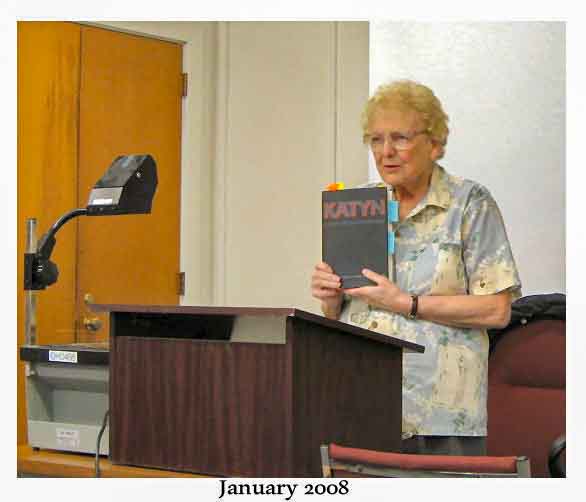

Anna Cienciała extended her interest in Polish foreign policy to the period of World War II. While examining the situation of Minister Józef Beck in Romania, trying to find out his failures in escaping internment (article Internowanie rządu RP w Rumunii we wrześniu 1939 r.), the professor became interested in the policy of the Polish government-in-exile (article The Foreign Policy of the Polish Government-in-Exile, 1939-1945: Political and Military Realities versus Polish Psychological Reality), then, after the German attack on the USSR, how the Sikorski-Majski Agreement was signed (article General Sikorski and the Conclusion of the Polish-Soviet Agreement of July 30, 1941: A Reassessment), and further on the Katyn case and the English-language source edition Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment (2007) in cooperation with Wojciech Materski and Natalia Lebiediewa.

Anna Cienciała during a lecture on Katyn in January 2008 with a volume of her book "Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment" (Source: RB)

The tragedy of the Warsaw Uprising shocked Anna Cienciała already in her early youth, but she was also prompted to take up this subject in her academic work after a personal meeting with wounded participants of the uprising just after the end of the war. The insurgents were then invited to Polish scout camps, and the Cienciałas also hosted in their home Nina Bartosiak, Anna's friend from before the war, who was seriously wounded in the uprising. Personal meetings at home and at the camp resulted in a lasting reflection on the uprising, and it was to that that Anna Cienciała devoted her first important academic work - her master's thesis from 1955 (The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 in the Light of Polish–Soviet Relations During World War II).

In subsequent years, while still dealing with the topic of Poland's place in international politics, she focused her attention on the Yalta Conference, the goals of British, American and Soviet policies (popular lectures Stalin's Changing Policies on Poland, 1939-1914; Britain, Poland and the Yalta Agreement, The Anglo-American Road to Yalta; *President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Poland in World War II *), as well as on the event opening a new chapter in Polish history - the end of World War II (lecture V–E Day 1945: The View from Eastern Europe).

Thanks to the materials of Prof. Cienciała's legacy, we can not only deepen our historical knowledge, but also learn the alchemy of research work, explore the process of creating scientific works, their conceptualization, creative torments, editorial corrections, reviews - in a word: hear "how the grass grows". It is not only a valuable source of knowledge about the life of the professor, but also a lesson in how to become a great researcher.

I would like to thank Ms. Roma Boniecka (RB) for her help in preparing the text and lending me the photos.

This text comes from the publication "...so that every fragment of history could be saved!", Archive Full of Memory, ed. Teresa Gallewicz-Dołowa, Wojciech Kujawa, Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw 2021, ISBN 978-83-8229-237-4, reproduced here with the publisher's consent.

The text was created as part of the Archive Full of Memories project:

We research the history of Poland in the years 1917–1990 partnering with historical research institutions from all over the world. We conserve, research, provide access, and store public documents, photographs, private letters, diaries, memoirs, films, audio and video recordings for future generations. Our donors also come from all over the world.