Anna Druś: Good morning. Anna Druś, editor of Wszystko Co Najważniejsze (All That Matters Most) and Serwis dla Polonii (Service for Polonia). With me today is Mr. Artur Szklener, director of the Fryderyk Chopin National Institute, which is organizing the 19th Chopin Competition this year. Good morning.

Artur Szklener: Good morning to all of you.

AD: The competition begins on October 2nd, so there's still time before the event, and we know from the qualifying rounds that it will be a unique event in many ways, a bit different from others. A record number of entrants. 13 Poles. Tell us about yourself, what you think will set this competition apart from previous editions.

AS: I think that, above all, the record number of pianists entering will make this competition extraordinary. It's already there, as we've already completed two stages. Just the initial two stages. This is a competition of an exceptionally high artistic standard. This has happened over the past decades, in fact, in the last few editions of the competition, that we've managed to rebuild the competition's prestige in the 21st century, I think, from its heyday, the 1960s and 1970s, when, let's remember, the competition's winners included such piano giants as Mauricio Polini, Martha Archer, and Gary Coulson. Today, pianists from all continents strive primarily to be able to perform in the first stage of the Chopin Competition.

Let's remember that there were over 640 entries. That was a record number. An absolute record not only in the history of the Chopin Competition, but also, I think, for any international music competition in the world. This shows, on the one hand, that the Chopin Competition has such a high reputation among pianists, but I also think it shows that the Chopin Competition offers the opportunity to build an international career. It offers a chance to be noticed in this very difficult artistic market. And as I said, pianists who enter, even in the first stage, are as if they were entering a certain international league, to put it in sports terms. And it's up to them how they shape their careers. I think the second element that truly distinguishes this competition is the growing, yet unprecedented, popularity of the Chopin Competition among listeners.

We're truly inundated with requests for tickets, for the opportunity to participate even for just one day, even for just one session. On the one hand, this presents a significant challenge for us, as the National Philharmonic Hall has limited seating capacity, but on the other, we're incredibly excited about it. This interest also translates into organizing a wide variety of events surrounding the competition.

Among other things, we call these zones music lover zones, though we don't hide the fact that these are zones modeled after sports fan zones. These are places outside the National Philharmonic and also outside Warsaw, where we want listeners to be able to experience live performances, but also create communities—not just in front of a laptop or TV—to be with us and participate in this great event. Finally, I wanted to mention the accompanying events, such as the temporary exhibition being organized here. We're on the terrace of the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw, on Tamka Street. Just behind these doors, one floor up, we've organized a completely unique temporary exhibition. We brought in around 60 objects from the Museum of Romantic Life in Paris to present, among other things, the context of Fryderyk Chopin's work—this Parisian context—to participants of the Chopin Competition and listeners.

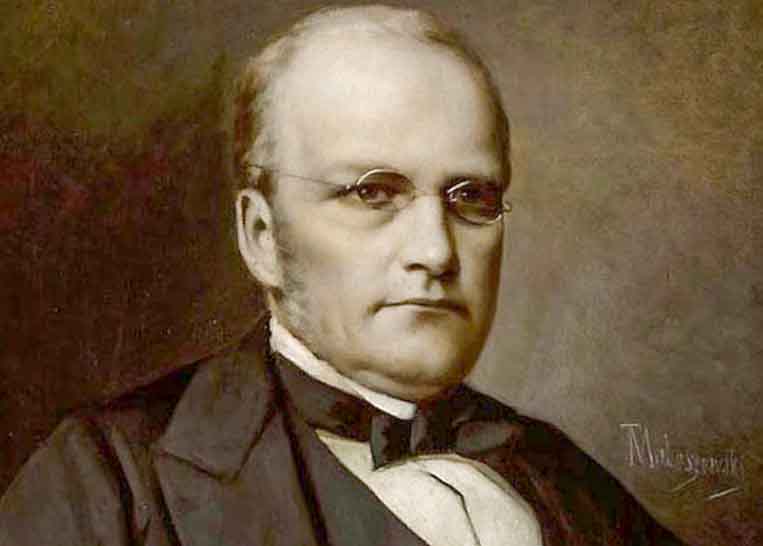

We present works by artists such as Arie Schaeffer, Aureon de la Croix, and a figure of immense importance to the composer, Georges Sand. We must remember that together they formed a kind of artistic center, a kind of artistic family centered in the Parisian center then called New Athens. It was a kind of bohemian society, but at a very high artistic level. And within this exhibition, "Romantic Life," as it is titled, we want to show the extent to which Chopin was the center of this entire world, and his music was highly valued. The exhibition centers on two objects: one from this world of the profane, the world of everyday life. It is a fan created, co-created by Georges Sand. After all, there are, where all these figures appear in allegorical form.

There, Chopin is a small hummingbird, a bird meant to transport viewers and listeners to another world, the world of art. On the other hand, as part of this exhibition, we are showing Chopin's original manuscript, one of his most outstanding works, the Ballade in F minor. This entire exhibition is accompanied by, or rather, is part of, a separate layer, a separate sonosphere, a selection of compositions that allow us to immerse ourselves in this Chopinian atmosphere.

In Żelazowa Wola, in the birthplace of Fryderyk Chopin, there's also a very interesting temporary exhibition, featuring puppets from a professional theater, the theater of George Sand's son, Maurice, who, as a visual artist, at one point specialized in creating precisely this type of puppet theater, inspired by Don Juan, which Chopin found as a kind of refuge in exile.

And all sources indicate that the inspiration for this theater, the first inspiration, was Fryderyk Chopin himself, who remembered similar experiences from his childhood in Warsaw. In short, the many different initiatives surrounding the Chopin Competition enrich it and ensure that we are accompanied not only by pure music but by many other stimuli and narratives.

AD: Right after the qualifying rounds concluded, you said that the standard of the preliminary auditions was so high that you were surprised that so many pianists chose the most difficult pieces, which usually appeared only at this October stage of the competition. Can we say today that the Chopin Competition is essentially a master's competition, even though it is dedicated to young pianists up to 30 years of age?

AS: Absolutely. And here, without any "buts" or compromises. The age of achieving a certain kind of mastery has moved so far that in previous editions, we lowered the age of participants, so now competitors can be as young as 16.

This demonstrates, on the one hand, that we are witnessing an extraordinary development in artistic education, that young, talented people simply have a place to learn and hone their piano skills. On the other hand, I think it also demonstrates a certain universality in Fryderyk Chopin's work. Chopin himself wrote many of the compositions that appear in the Chopin Competition as a very young man. It's worth noting that he wrote both concertos—the pieces appearing in the competition finals, the concertos with orchestra—when he was in his twenties.

Being a teenager, or perhaps just around 20, creates a certain age parallel, meaning the participants share the same natural instincts, certain predispositions. Of course, Chopin was an absolutely exceptional young man, a genius, one of the most outstanding creators—not only as a pianist but also as a musical creator—in history, which makes interpreting his compositions particularly difficult. But this predisposition, this certain touch of youthfulness, not only doesn't hinder but can be a very important asset.

AD: I had the opportunity to speak with one of the Polish participants, Jahuda Prokopowicz, who is one of 13 Poles qualified for the first stage of the competition. I asked him about how Generation Z interprets Chopin, because this year's edition will effectively be one in which Generation Z interprets Chopin. When did you listen to these Generation Z interpret Chopin? Was there anything that distinguished them from previous generations, or is it simply a universal youthfulness?

AS: I think that something that distinguishes young pianists today is their incredible mastery of the piano. And I'm not sure if this is a characteristic of Generation Z, or simply a result of the process I mentioned earlier, the improvement of educational methods. And I think, to some extent, it's also the fact that our world has shrunk, that travel is so easy, that young pianists themselves can study with many teachers, and that very experienced teachers often change their locations or participate in master classes in many places around the world. All of this makes one look with envy at the possibilities young artists have. What possibilities they have, not only in terms of playing quickly, but also in fully mastering the instrument, with a whole range of emotions, sounds, and various techniques. And if I were to focus on anything when trying to help young artists, it wouldn't actually be this aspect of proficiency, but rather the question of individuality.

Because we must remember that Fryderyk Chopin was an absolutely unique creator. Chopin drew on the legacy of the past, but transformed it to such an extent that each of his works is unique. Moreover, Chopin himself avoided self-repetition, so his creative path is a constant search for new paths. Not only for development, but above all for expression. And now, I think, the most difficult task at the Chopin Competition is achieving a certain balance between one's own original expression, with the display of one's personality, a certain desire to stand out, which is very natural for every composer, especially for young ones. And on the other hand, maintaining these desires, these needs, within certain stylistic constraints.

On the one hand, I would encourage everyone to show their individuality, to avoid copying even the best performances, which, thanks to technology, are readily available to us in countless numbers. But on the other hand, even when we show our individuality, let's stick to the source and adhere to certain norms, considering how we understand Chopin's work today. And I assure everyone that the gap between the two is enormous. You don't have to revolutionize your thinking about classical music to show your individuality.

AD: Speaking of revolutionizing classical music, one last question about a film. This year's competition is accompanied by the premiere of the film Chopin, Chopin. It's another major Polish work dedicated to our national composer.

You've already seen it, because I asked you about it, but I didn't ask about your impressions. And at the same time, how does this film differ from your previous ones? Was there anything in this film that surprised you or made you think about something you hadn't encountered before?

AS: Not only did I have the opportunity to see this film with my team, and I did so many times, but from the very beginning, and even before the shooting stage, during the preparation stage, even during the stage of polishing the script, we took a very active part in the creation of this film.

Among other things, our participation, our commitment, and the filmmakers' approach result in several elements that absolutely distinguish this film from other Chopin biographies, with the caveat that this film is not, strictly speaking, a biography. It's more of a psychological perspective, in which, by nature, with this type of approach, many biographical aspects simply cannot appear, because the filmmakers focus on the internal struggle, but in any case, on the inner world of Fryderyk Chopin. But something that sets this film apart, I think, beyond these purely narrative aspects, is the musical layer. In this film, first of all, Erik Kuhn, the actor playing Chopin, put in an absolutely titanic amount of work to learn the fragments of the pieces Chopin plays. Thanks to this, we actually see the actor performing on camera. These are often very subconscious signals, but they speak volumes. Filmmakers are usually not allowed to show the actors' hands, and even when they do, it's in a very simplified way.

Here, I take my hat off to Eryk's achievements. But when it comes to the musical aspect, they managed to combine Eryk's visual prowess with the outstanding mastery of Tomasz Ritter, who, in effect, recreates fragments of Chopin's works for the soundtrack, but goes much further because he composes Chopin improvisations. And I'd like to draw attention to this, because it's absolutely the first time in history that I know of—not only in the history of cinematography, but in general discussions about Chopin's artistic work—that an artist undertakes a certain reinterpretation or creation based on Chopin's model, both improvisations when Chopin simply plays with friends, but also improvisations intended to recreate his creative process. We know that Chopin spent a very long time refining his works, often creating multiple versions, returning to the originals, and so on. This process of refining the final stage of creation was very difficult for him. And this aspect also appears in the film, which I consider particularly valuable.

And finally, the last element I wanted to highlight is the fact that Chopin speaks about music in a way that, as a musicologist, I believe is consistent with his views. This is also unusual, especially in a psychological film, where the primary goal isn't to convey certain facts or factual information, but rather to create certain impressions or evoke certain emotions, which I think this film does very effectively.

AD: Thank you very much for your time and conversation.

AS: Thank you very much.

AD: My guest was Mr. Artur Szklener. See you soon.