The year 2022 was announced by the Sejm of the Republic of Poland as the year of Józef Mackiewicz. So there were many opportunities to bring to light the figure of the writer from the darkness of non-existence to which he was condemned in the times of communist Poland. The fruits of research into the work of this unique political writer, unique in his time and one-of-a-kind, gave birth to many scientific sessions, analyses, publications, documentaries devoted to his life and work and reissues, or first editions of his books and letters, in Poland.

- Mackiewicz w 1919 r. (Source: Wikipedia)

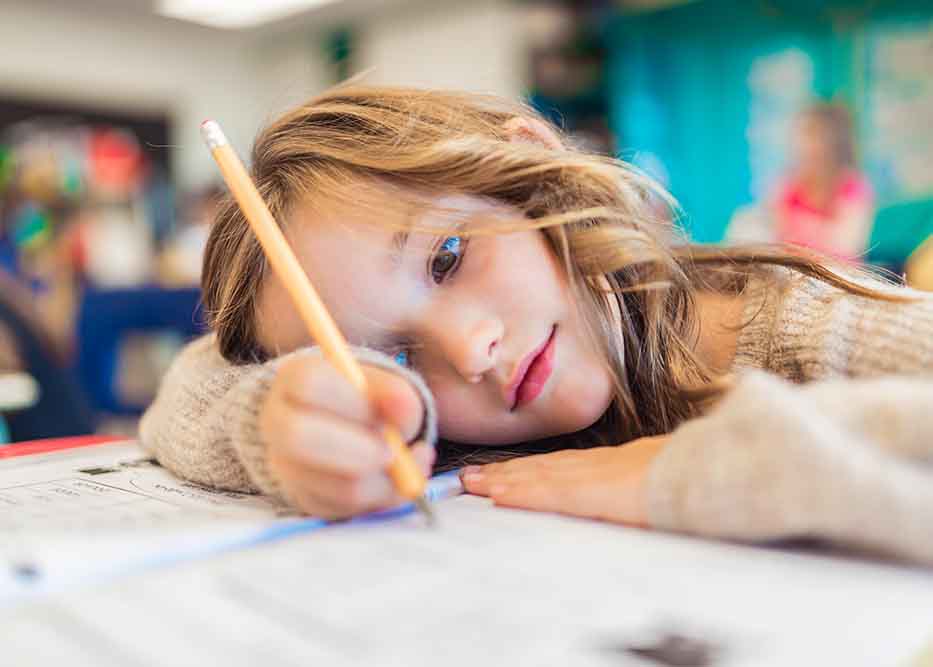

The time has come to bring this character closer to the next generation of Poles living or born in emigration, especially since Józef Mackiewicz was a Polish writer who lived most of his life in emigration. This is the right time to say why emigration did not like him and his homeland condemned him to oblivion.

Józef Mackiewicz, whose character and views were shaped by the multicultural community of the Polish Borderlands and two world wars, is a writer and publicist of the twentieth century.

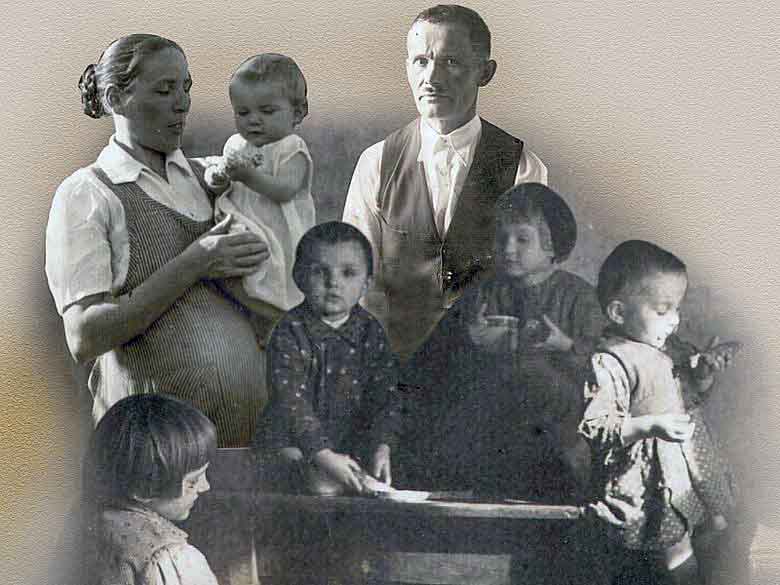

He was born in 1902 in St. Petersburg. He came from an impoverished Polish landowning family. His father, Antoni Mackiewicz, although he boasted of a coat of arms, was already a commercial entrepreneur. In St. Petersburg, he was the director and co-owner of the wine import company "Fochts i Spółka". His mother — Maria, née Pietraszkiewicz — was related to the family of a Philomat, friend of Adam Mickiewicz, Onufry Pietraszkiewicz. Both parents' families were connected with Lithuania and Vilnius, the city that played a significant role in the writer's life.

Parents Antoni Mackiewicz and Maria, née Pietraszkiewicz (Source: Wikipedia)

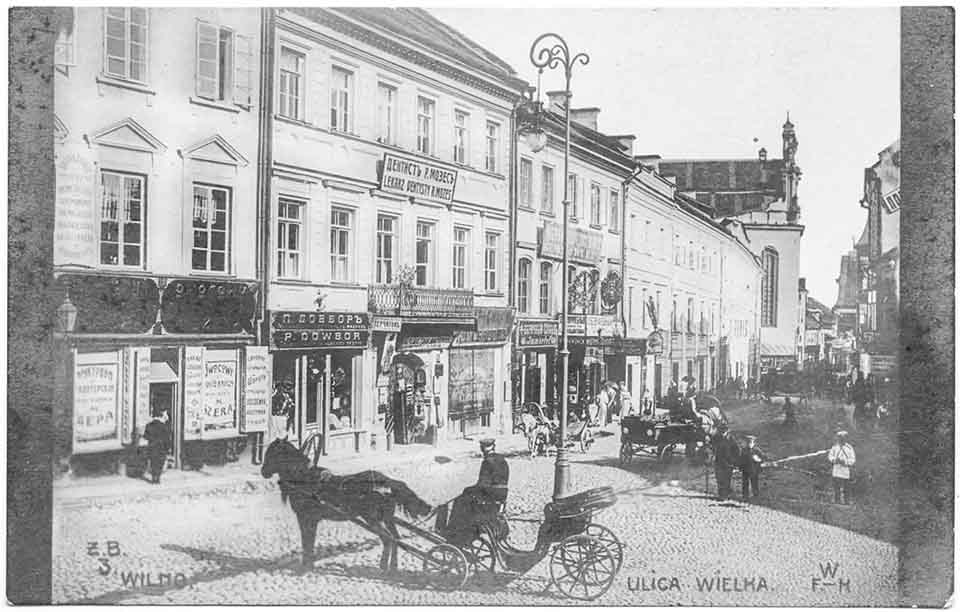

In 1907, the Mackiewicz family moved to Vilnius. Józef and his elder brother Stanisław were educated in elite Russian schools. Józef attended a private classical gymnasium named after Vinogradov. He did not finish school, because the ongoing World War I and pro-independence organizations active in Vilnius dragged him into the whirlpool of action. Seventeen-year-old Józef, then a sixth-grade junior high school student, voluntarily joined the army and took part in the Polish-Bolshevik war. He came close to death many times and learned the nature of the Bolsheviks. These experiences will be echoed in the novel Left Free (Lewa wolna).

In 1923, Stanisław Mackiewicz founded the newspaper Słowo (The Word), where his younger brother, Józef, took up work as a journalist-reporter. Contrary to the popularity and success of Stanisław, Józef Mackiewicz did not enjoy either a very successful personal life, or the fame of an outstanding writer.

He released his first articles in the early 1920s in the daily Słowo, published by his brother Stanisław, with whom he collaborated until the outbreak of the war. He made his debut as a writer in 1938 with a volume of reportages "Bunt rojstów", which was a great publishing success and gained recognition from critics and writers, including famous writer and traveler S. Ferdynand Ossendowski.

Editors of the newspaper Słowo ca. 1937 r. — Józef Mackiewicz in the middle (Source: Wikipedia)

"Bunt rojstów" is his first, but excellent, collection of reports about people living in the eastern Borderlands and about how officials from Warsaw try to "manage" their lives (i.e. make their lives difficult at the economic level), completely misunderstanding that they have their own customs and better know the land they live on, better know what is good for them. The author definitely takes the side of the rebels and becomes their spokesman. In protest against the policy of the state towards national minorities, against the demolition of Orthodox churches in the Chełm region at the time, he converted to Orthodoxy.

Słowo was published until 1939, until the outbreak of the war. In the editorial office, Józef Mackiewicz meets the journalist and poet Barbara Toporska, who — after his two failed marriages — will become his beloved wife, collaborator, and friend for the rest of his life.

Vilnius in 1912 (Source: Wikipedia)

After the Red Army entered Vilnius, Józef Mackiewicz briefly publishes Gazeta Codzienna (Daily Gazette). He strongly refuses to cooperate with the Soviets when they take Vilnius. In June 1941, the Germans occupied Vilnius and offered him to edit the magazine in Polish, but he flatly refused. However, in Goniec Codzienny (Daily Courier), a magazine published in Polish, but by the German authorities, he published several articles signed with the initials J.M. This fact will be fraught with consequences later in the author's life.

At the turn of 1942 and 1943, the military court of the Home Army recognized him as a collaborator and sentenced him to death. Although Sergiusz Piasecki, responsible for the executions, did not carry out the sentence, and the commander for the Vilnius district, Col. Aleksander Krzyżanowski acquitted him, the writer struggled with the stigma of this accusation all his life.

In May 1943, after the discovery by the Germans of the graves of Polish officers in Katyn, at the request of the Germans and with the consent of the authorities of the Home Army, he went to Katyn as an observer of the exhumation of the corpses. He was one of the first witnesses to this crime. He went there to reliably tell the Polish society about what he saw there, who in fact committed the Katyn massacre. In an interview published in Goniec Codzienny entitled "I saw with my own eyes," he describes what he saw:

The sight of such a large mass of corpses caused a great nervous shock in all those who arrived. I personally was not able to take up any work at first.

After visiting Katyn, in the same year, 1943, Józef Mackiewicz witnessed the massacre of Jews in Ponary. From the mid-1930s, the Mackiewicz family lived in Czarny Bór, 15 km (9 miles) from the center of Vilnius, not far from the Ponary railway station, where Jews were brought, shot and buried in mass graves, in the pits of the "Base" — an unfinished aviation fuel depot. Mackiewicz, in 1945, would publish a reportage about this event entitled "Ponary-Baza". It is one of the most important texts describing the genocide in World War II. In Ponary, in the years 1941–1944, the Germans, with the participation of Lithuanian collaborators, may have murdered up to 100,000 people. The largest number were Jews, but among the victims were also Poles, Belorussians, Roma, Tatars, Lithuanians, and prisoners of war from the Red Army.

- Mackiewicz, Vilnius, 1923 (Source: instytutksiazki.pl)

In the spring of 1944, when the Soviet front was approaching Vilnius, the Mackiewicz family left for Warsaw, and on the eve of the Warsaw Uprising, they went to Krakow. In the autumn of 1944, Józef published the brochure "Optimism will not replace Poland for us". In it, he believed that one should prepare for the Soviet occupation, which might turn out to be worse than the German one, because it would lead to the destruction of the entire nation. This pamphlet is one of the finest texts of political realism.

At the beginning of 1945, through Vienna, after many hardships, he gets to Italy and to the 2nd Corps of General Władysław Anders, where many outstanding writers and artists had already found their refuge (including GH Grudziński).

The peer court clears him of allegations of cooperation with the Germans, but this will not take away from him the odium with which he will struggle almost all his life. Commissioned by the Office of Studies of the 2nd Polish Corps, J. Mackiewicz prepared a white book about the Katyn massacre — "Katyn Crime in the Light of Documents", with a foreword by General Anders, which was published in 1948.

In the years 1946-1947, J. Mackiewicz began to regularly publish in several emigration papers, including in the Parisian Kultura (The Culture), London's Wiadomości (The News), the weekly Lwów i Wilno (Lviv and Vilnius). He also collaborated with the Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian émigré press.

In 1947, on one of the last transports with the 2nd Corps, he arrives in London and starts collaborating with the weekly Wiadomości. In 1949, Mackiewicz published in Switzerland his book, translated into German, about the Katyn massacre “Katyn. A crime without trial or punishment." His views contained in publications push him to the margins of emigration life.

Józef Mackiewicz always swam against the current, he had his own opinion, he was in service of no one, he submitted to no authorities. He believed that the view that the ally of our allies, which is the Soviet Union, is wrong and that the view that we have one enemy, which is Germany, is also wrong. This attitude did not win him supporters among emigrants — on the contrary, he was misunderstood and felt alienated.

In 1955, the Mackiewiczes move to Germany, to Munich, where Barbara Toporska initially finds a job at the "Voice of America" radio. They live in very modest conditions, initially in a rented tiny apartment, then in a house with a garden. They live on unemployment benefits or meagre royalties from small publications. They were unofficially supported financially by private individuals. Barbara Toporska even tries to earn money by fixing women's stockings.

Here, in 1955, Józef writes The Road to Nowhere (Droga donikąd). This book describes the reality differently than memoirs or articles from the war period, it does not talk about martyrdom, or labor camps. He talks about a spiritual encounter with Bolshevism. The following novels, "The Left Is Free" (Lewa Wolna), "You Must Not Talk Loud" (Nie trzeba głośno mówić) and "The Victory of Provocation" (Zwycięstwo prowokacji), take up the same subject and completely change the narrative that the literature told about the war of 1920 and the Soviet-German war.

The war of 1920 was a war to save the European, and perhaps the world's, civilization based on Roman law and Christian morality, which had been built for years. In 1956, when Władysław Gomułka comes to power in Poland and announces the Polish way to socialism, and Radio Free Europe supports Gomułka's line, Mackiewicz again finds himself in opposition, disagreeing with the editors of RFE, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański and Zdzisław Najder.

In the 1970s, in his books "In the Shadow of the Cross" and "The Vatican in the Shadow of the Red Star", J. Mackiewicz criticized the policy of the Catholic Church towards communism. In his opinion, the Church has ceased to be a moral bulwark in the fight against communism.

Mackiewicz was a staunch anti-communist in all his publications. He showed the communist system as a system for the destruction of humanity in the mental sphere, corrupting man, as a system of oppression from under which it is difficult to get out.

For over half a century, from 1945 to the abolition of censorship in 1990, Józef Mackiewicz was completely banned as a writer in Poland. His books were nor present in bookstores, his name could not be found in any dictionary or encyclopedia. For Polish readers, Józef Mackiewicz was an unknown, non-existent writer. Over the years, he has been deliberately erased from human memory. As a student of Polish studies at the University of Warsaw in the 1960s, I had not heard a word about the writer Józef Mackiewicz. In the times of Solidarity, barely something in the secondary circulation was catching on, and even in the 1990s — when it was the best time to publish his books — in Poland, due to the different attitudes of the then decision-makers, Mackiewicz was not being published.

Józef Mackiewicz (1902-1985) (Source: Polish Museum in Rapperswil/IPN)

One of the contemporary analysts of Józef Mackiewicz's work, Professor Włodzimierz Bolecki, who devoted almost forty years to explain the so-called Mackiewicz's case regarding his alleged collaboration with the Germans, sums up his opinion about this extraordinary writer:

A writer like Józef Mackiewicz is born once in a century, or even less frequently (…). He himself defined his writing formula directly: he said "I am all for accuracy, because only the truth is interesting".

It is safe to say that Józef Mackiewicz has something extraordinary in his following, namely that he is being discovered as an increasingly up-to-date writer, as a writer who wrote the truth, as a writer from whom we can learn to understand the world. As a writer, which may seem incredible, but whose topicality becomes even more relevant today, when we see and learn about contemporary history, it is safe to say that Józef Mackiewicz has a future ahead of him. This is the writer of the future.

Editor's note: Józef Mackiewicz died in Munich on January 31, 1985, at the age of 83.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.