What a man needs most to be happy is a taste of freedom and a sense of truth and justice. Poles, despite crazy efforts in the fight against Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism, as a result of political agreements concluded after World War II, experienced a sense of moral injustice, material harm, and yet another enslavement. It was all the more painful given that we are a nation that has always loved freedom from the beginning of its existence.

The more than fifty-year period of communist enslavement was for us a period of hard trial, waiting for full independence. We persevered in hope, sustained by the Polish word reaching the country from our compatriots from the West, from those who remained in exile after the war.

The new intellectual elites were shaped and promoted by the work of the team of the Parisian "Kultura", and the spoken word, transmitted via the radio from Polish-language radio stations in London and Munich, reached a wide audience. Especially the one from Munich, led by Jan Nowak-Jeziorański and the elite of Polish emigrants - Radio Free Europe (RFE) shaped the attitudes of Poles.

Who was Jan Nowak-Jeziorański?

His real name was Zdzislaw Jeziorański. He used the pseudonym Jan Nowak for the first time in 1943, when he was going as a courier of the Home Army Headquarters on a mission to London, to the Polish Government-in-Exile. Later, he used this surname and first name so often in his journalistic activities — especially as the creator and editor of RFE, that the pseudonym became so closely related to his character that it became part of his real name.

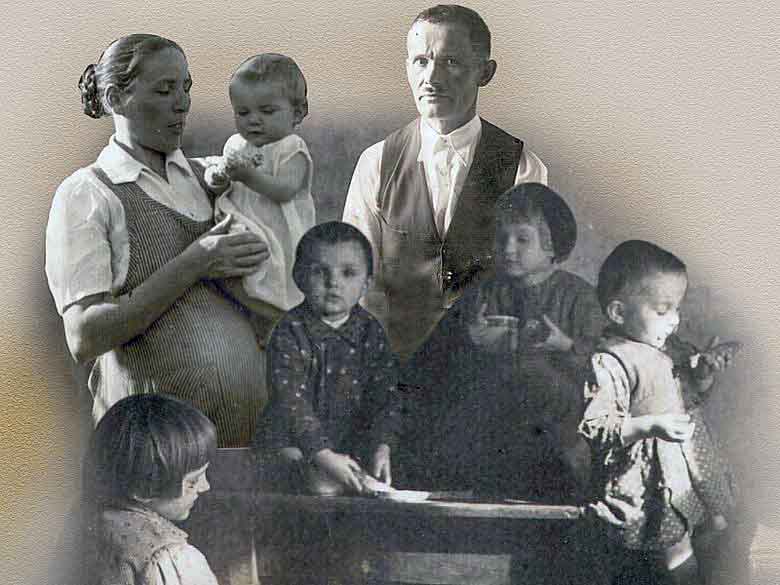

Jan Nowak-Jezioranski in 1936 (Source: Wikipedia)

Zdzisław Jeziorański was born on October 3, 1914 in Berlin, in an assimilated Jewish family with roots dating back to the 18th century. He studied in Polish schools. He attended the State Gymnasium of Adam Mickiewicz in Warsaw. He was friends with the son of Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski, and the founder of Gdynia likely had an influence on Jeziorański's undertaking economic studies. He was a scout of the 3rd Warsaw Team. Fr. Józef Poniatowski.

After graduating from economic studies in 1936, he started working as a senior assistant in the department of economics at his alma mater, the University of Poznań. In 1937, he graduated from the cadet school and served in the horse artillery squadron. He took part in the September campaign of 1939 and was taken prisoner by the Germans. He managed to escape from captivity and immediately joined the activities of the Polish underground.

From 1940, he was active in the Union of Armed Struggle, which in 1942 was renamed the Home Army. He collected and distributed propaganda materials. At the request of the Home Army commanders, he also worked in the German administration, where he obtained specimens of prints and documents of the occupant that were helpful to Polish underground organizations.

In 1943, he volunteered to be a Home Army courier to the Polish authorities outside the country. He described his missions in the book "Kurier from Warsaw" and this is how he will be known to the Polish emigration. In the 2nd Corps of General Anders, he learned how to operate a radio station and parachute jumping. As Cichociemny (The Silent-Unseen), he landed many times in occupied Poland.

He was the last emissary to reach the capital before the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. He fought in the uprising and, losing hope of victory, on September 7, 1944, he entered into a romantic, impromptu wedding with "Greta", Jadwiga Wolska, a liaison officer. On the eve of the capitulation, acting on the orders of the commander of the Home Army, General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, he set off for London. He took away hundreds of documents and photos. Both he and his wife survived the war. Jadwiga emotionally and professionally supported her husband's political and journalistic activities in exile. After the war, they stayed in the West. In the years 1948–1951, Jan worked in the editorial office of the Polish Section of the British BBC radio station.

BBC Radio - This is London Calling.

The first BBC broadcast in Polish was transmitted on September 7, 1939, seven days after the start of World War II and four days after Great Britain entered the war with Germany. Its jingle was the letter V beginning the word "Victory" in Morse code. It spoke seven languages to the world at the outbreak of the war, and forty-five by the end of the war. The first to speak on its waves was the Ambassador of the Republic of Poland in London, Edward Raczyński. He spoke of Poland's struggle "in the name of the principles of freedom and justice, which it has not betrayed in its history."

The broadcasts of the Polish section of the BBC very often featured representatives of Polish civil and military authorities. Initially, the broadcast was only 15 minutes long, but by the end of the war it had grown to twelve fifteen-minute episodes a day. After the conclusion of the Sikorski-Majski agreement (the agreement between the Polish Govermnet-in-Exile and the USSR - ed.), the broadcast content was subjected to meticulous analysis by the British. Anything that the British might consider anti-Soviet was subject to censorship. Polish interests were then at odds with British interests. Katyn's Massacre, about which the BBC radio was silent, could be an example of this situation. Criticism fell not on the murderers (the Soviet Union) but on the victims — the Poles, who demanded an explanation of the murders of Polish officers.

Despite the strict supervision of the British leadership, the broadcasts were of great importance to the Poles. They informed about the fights on the Western Front, allowed to maintain contact with the Polish armed underground, aroused (often in vain) the hope for help in winning freedom. They were the only contact between occupied Poland and Poles in the West. At the end of the war, the team of the Polish section of the BBC consisted of 17 people, among whom were outstanding personalities from the world of culture and science, among them an activist of the ZPwN (Union of Poles in Germany), a Warsaw correspondent of the PAT (Polish Telegraphic Agency), an officer of the Polish Armed Forces in the West and later professor of history at the UWM (Wisconsin State University in Milwaukee) Marian Kamil Dziewanowski.

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański's activity in the BBC radio in Great Britain helped to raise the awareness of the Western public about the scale of Nazi crimes in Poland.

In the period of the Polish People's Republic and the then-prevailing censorship, the authorities tried to limit access to the reception of Polish-language BBC broadcasts, which were an opportunity for listeners to learn information from independent sources. In addition to news and commentary, journalistic, popular science, cultural and religious programs were broadcast. Listening to the radio from behind the Iron Curtain was a crime until the 1980s (until 1989), punishable by a fine, or even imprisonment.

In the early 1990s (after Poland regained independence - ed.), the Polish Section of the BBC began to cooperate with the Polish Radio.

Due to reorganization at the BBC, on October 25, 2005, a decision was made to dissolve 10 language sections, including the Polish one. The money saved in this way was to be used to create an Arabic-language television. In the last year of operation, a total of 58 people worked in the Polish section - 32 in Warsaw and 26 in London. The Polish Section of the BBC broadcast its last transmission on December 23, 2005

History of the Polish section of RFE

The second, after the Polish Section of the BBC radio, important Polish-language source of information was Radio Free Europe (RFE), which was established in 1949 in New York on the initiative of the "National Committee for a Free Europe". Radio Free Europe broadcast programs to the countries of the Eastern Bloc (the so-called countries of "people's democracy"), which after 1945 found themselves in the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union, and to the Baltic republics incorporated into it (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia). Radio Svoboda broadcast its programs to other republics of the Soviet Union.

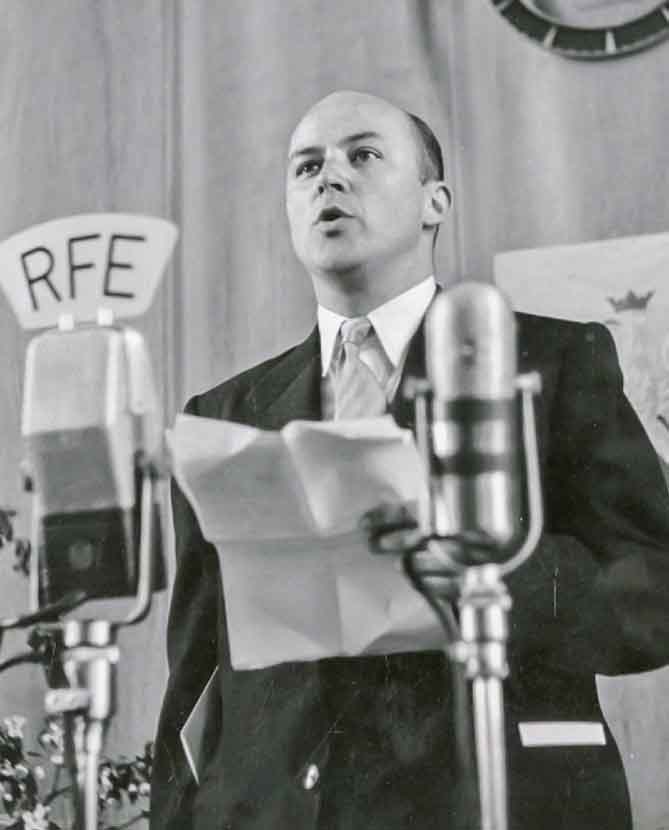

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański at RFE (Source: Wikipedia)

In the initial phase of organizing Radio Free Europe, the heads of the Polish section in New York were the diplomat Lesław Bodeński and the journalist Stanisław Strzetelski. After the outbreak of the Korean War, the US authorities decided to modernize the station and give it a highly professional broadcasting profile. This was to be achieved by locating the entire radio station directly in Munich and ensuring its proper technical, financial and journalistic service. After consultations with representatives of the Polish Government in Exile, in December 1951, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, the legendary courier and emissary of the Home Army Headquarters and the Polish Government in Exile, was entrusted with the function of the head of the Polish Broadcasting Station in Munich. Even before the end of the year, Nowak-Jeziorański appointed an editorial staff consisting of experts from the pre-war Polish Radio, PAT correspondents, Polish journalists and political columnists. Most of them were former officers of General Władysław Anders' 2nd Corps.

The first RFE broadcast, the Voice of Free Poland (Głos Wolnej Polski) was transmitted from Munich to Poland in 1952 on the symbolic day of May 3. After the sounds of the national anthem, in his inaugural address to his compatriots, J. Nowak-Jeziorański said: "Know that no curtain of falsehood and lies will ever be able to obscure your true face, the face of Poland." He also stated that the most important task of RFE towards the country will be the fight to preserve Polish identity and defend society against Sovietization.

The tool of this fight was reliable information about events in Poland and in the world, opposing the falsification of Polish tradition and history. Despite powerful jamming, the RFE program effectively broke the communist information monopoly. RFE provided reliable information about events in the country and in the world; it was the first to publish information about Poznań in June 1956, about the intervention of Warsaw Pact troops in Czechoslovakia, about accidents on the coast in 1972, about "Solidarity". It supported the opposition in the country, exposed the crimes committed by the Security Services of the People's Republic of Poland, defended the Catholic Church, and took up the issue of repatriation of Poles from the territories of the Soviet Union.

The most eminent Polish emigrants, artists, and dissidents who fled the country, who exposed the activities of the communist authorities, collaborated with the radio station. RFE was listened to in the country. Poles, despite threats and punishments, sought a wave of free speech of truth at night and confronted them with the regime's propaganda. They expressed their attitude towards official information by boycotting the Polish media, for example by turning off the television during the evening news and going for a walk at that time. Undoubtedly, RFE had a considerable influence on shaping the awareness of Poles and on subsequent rebellions against the communist authorities. The cooperation of Jan Nowak-Jeziorański with Jerzy Giedrojć, their extensive correspondence with Polish and emigre artists, and the publication of alternative circulation books — banned in the country — made it possible to maintain Polish culture on a world-class level and to preserve its achievements until independence.

In the Polish American Congress

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański managed the Polish Radio RFE continuously until January 1, 1976.

After leaving RFE, he was active in the Polish American Congress for 20 years. He actively supported Poland's efforts to join NATO. In 1994, he began publishing a series of columns "Poland from afar", broadcast on Channel I of the Polish Radio. In July 2002, after 57 years of emigration, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański returned to Poland and settled permanently in Warsaw. At that time, he made cyclical comments on the radio under the title "Poland from Close-up". He died on January 20, 2005 in Warsaw. He was buried in Polish soil, with honors, with the participation of Polish and foreign delegations, on January 26, 2005.

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański in 2002 (Source: Forum, Photo: Jacek Lagowski)

During his lifetime and after his death, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański was honored with many state and honorary awards. The Polish Sejm (the Parlament) declared the year 2014 after him.

He was an extremely active political activist, the author of many books, hundreds of articles, he was involved in many open and less open political actions. Without the involvement of people such as Jerzy Giedrojć and the creators of the Parisian Culture, as well as Jan Nowak-Jeziorański and RFE, Poland's full independence would not have come so quickly.

It is extremely important to remember how much Polish emigrants have done for the Homeland, so that they will take their rightful place on the pages of history textbooks, and most importantly in the minds of the young generation as intellectual and moral authorities on which we build our national identity.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.