On Tuesday, March 10, 1891, sixteen-year-old Michal Grochowski stepped aboard the steamship SS America at Bremerhaven (Bremen), Germany. Michal had never seen a ship in person, nor had he ever laid eyes on the ocean. He had spent his entire life in the farmsteads of rural Łobżenica, Poland, about 40 miles west of present-day Bydgoszcz.

Artists rendition of a steamer similar to SS Amerika which carried the Grochowski family to the US (Source: author's archives)

Michal’s life had not been an easy one. Born on August 7, 1875, Michal’s parents weren’t married. His father, according to family tradition, had been a Polish noble who abandoned his young mother, 22-year-old Magdalena Kopidura, shortly after his birth. This “count of no account” as he became known in family lore was likely the local landlord for one of the manor farms in the area.

Michal wasn’t alone on his journey. His mother had married 21-year-old Anton Grochowski on October 7, 1879, at Łobżenica and the family was traveling with Michal’s half-siblings, John, Francisca, and Joseph. Magdalena was also pregnant and due to deliver within weeks. They had made the 500-mile trip from Bydgoszcz via train and brought only a few keepsakes for the long trip to their destination in America. It may seem that the family was leaving in desperate circumstances and, to some extent, they were.

Łobżenica today (Source: Wikipedia)

The area around Lobżenica hadn’t been called Poland for nearly 100 years, despite being mostly Polish speaking. For many years, the area had been part of the ever-expanding German Prussian Empire and German policies toward the area’s Poles had become increasingly draconian. An overt policy of “Germanization” had been put into force in 1871, which made life incredibly difficult for the area’s Poles. For many years, wealthy German elites known as the Junkers had taken control of large swaths of farmland in western Poland and ran their estates as feudal fiefdoms, treating the area’s Polish population as serfs. As late at the mid-1800s, many area Poles still lived and worked in this medieval system where they were literally owned by the local lord. Some were tenant farmers, granted a plot to which they held title, but the majority served at the pleasure of the local lord. They worked seven days a week, tilling the lord’s fields, usually until sundown. After hours, they were permitted to work their own small plots, from which they subsisted.

The church in Łobżenica today (Source: Wikipedia)

While life under the Junkers was hard, it could be equally repressive under the local Polish nobles. The “szlachta,” as they were called, often had their own semi-feudal estates with equally harsh conditions, but increasingly, their estates were being carved up among German settlers. Beginning in 1886, the “Prussian Settlement Commission” had been established to purchase lands from Polish owners for settlement by ethnic Germans, and the Prussian government began to institute anti-Polish policies, designed to eradicate Polish culture. Instruction in schools was mandated to be done in German and the Roman Catholic church began to experience repression. By the end of the 1800s, many Catholic parishes had gone underground, and mass was held in secret. Worse yet, Polish men were being conscripted into the Prussian Army for 20-year terms. City names were being Germanized, Poznan become Posen, Bydgoszcz becoming Bromberg, and little Łobżenica became Lobsens. Even names given in civil records had to be recorded as German, Jan becoming Johann, Maciej becoming Matthias. Poles were increasingly becoming second-class citizens in their own land.

It was from this difficult world that the Grochowski family, and hundreds of thousands of other Poles, sought escape. Fortunately, the Germans had no problem allowing the Poles to leave. The German government actively made travel brochures available to rural Polish peasants and they worked with German shipping lines to facilitate cheap and relatively convenient transportation to America for Poles. For around three month’s wages, a rural Polish family could purchase tickets for both rail transport to Bremen and ocean transport to America. Once in America, several popular destination cities were available by train, including Chicago, Buffalo and Pittsburg. Milwaukee, however, was one of the most popular destinations for rural Poles from the Poznan and Bydgoszcz areas, as it had developed a robust Polish community as early as 1870 and many area Poles already had family there. Michal’s family almost certainly chose Milwaukee for this reason. The Grochowski family appears to have known the Czaplewski and Sikora families, which were already in Milwaukee and the families later intermarried.

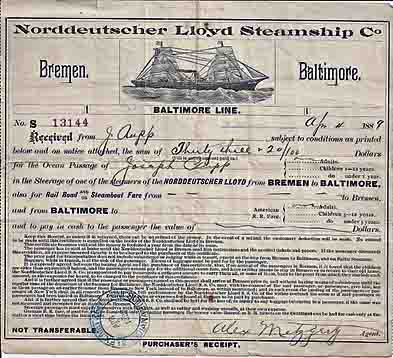

Steerage class ticket from Bremen to Baltimore in 1889 (Source: author's archives)

The trip from Łobżenica to Milwaukee was not without peril. Conditions on the immigrant ships were poor, particularly for steerage passengers. The popular Norddeutscher-Lloyd line maintained a large fleet of “immigrant ships” that ran to New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia from Bremen and Hamburg. These ships had a few cabin class berths, but were mostly designed with large, open areas below deck where hundreds of steerage class passengers ate and slept communally. After only a few hours at sea, most Poles were miserably sea-sick and quickly became dehydrated and weakened. Food was prepared and served below decks and rats were a constant companion. In the stuffy, crowed conditions below decks, illness was rampant and it was not uncommon for one or two passengers out of 100 to die en-route. Likewise, it was also not uncommon for children to be born on the voyage. This was the case for Michal’s half-brother Anton, whom Magdalena delivered on board the SS Amerika shortly after leaving port. Some ships embarked with a medical officer who was responsible for treating the ill and assisting in childbirths, but often passengers had to rely on the help of their fellow travelers.

Baltimore’s Immigration Piers, where the Grochowskis arrived in America (Source: Wikipedia)

Upon arriving in Baltimore, the family disembarked at the Locust Point Immigration Pier No. 9. There, they were processed in the same fashion that New York arrivals were processed at Castle Garden and, later, at Ellis Island. They were examined for disease, mental defects, moral character, and questioned to ensure they had a destination and the means to get there. The vast majority of immigrants boarded a train as soon as possible. The Grochowski family were almost certainly expected by friends or relatives in Milwaukee, as by 1891, Poles had been emigrating there for over 20 years.

Baltimore’s Locust Point Immigration Pier No. 9, c. 1890 (Source: author's archives)

The relief experienced upon arrival at Milwaukee must have been tremendous. Michal got off the train and immediately walked into a vibrant Polish industrial community, where people shared his language, culture and optimism. Work was plentiful and opportunity was everywhere. Michal’s rural Polish family would have been astounded at the range of food, housewares, and goods available for purchase in industrial America. The Grochowski family soon joined St. Josaphat’s parish and settled in a Polish flat at 945 Greenbush Street on what would today be S. 4th Street. The area is now under the I-94 freeway.

Bremen harbour (Source: author's archives)

An interesting characteristic of Milwaukee’s first-generation Poles was a notable desire to dissociate from their old lives in Poland. Milwaukee Poles almost never mentioned their places of origin within Poland on their civil or church records and relatively few stories of the “old country” were passed down. Likewise, photos or letters from the old country are rare among Milwaukee’s 19th century immigrant families. This is partly due to a desire to shed the old political, regional, and class identities that had been built into 19th century Polish society. The Poles were now Americans and they deeply embraced the egalitarianism and new cultural identity that America engendered. It is also true that many family members still in Poland were not literate and few had money for luxuries such as photographs. As such, most emigrating Poles of the 1870s to 1890s were truly leaving their friends and families for good and would never see or hear from them again.

By 1900, the Grochowski family had grown to include Albert and Rose Grochowski, but sadly, Michal’s mother Magdalena died on January 26, 1899 at the age of 45. Magdalena’s official cause of death was Pleurisy, but like many deaths in industrial 19th century Milwaukee, the actual cause was Pneumonia.

Obituary of Magdalena Grochowska, 1899 (Source: author's archives)

Although life in 1890s Milwaukee was infinitely better than that in Poland, it was still difficult by today’s standards, and a good number of people born today would not have lived to adulthood at that time. Most of Milwaukee’s Near South side did not have running water until the 20th century and hot running water was not common until after WWII. Homes were heated by coal and smoke was a constant companion. Residential dwellings on the near south side didn’t have boiler driven heat until the 20th century and bedrooms would often fall below freezing at night. Bathing was a once-a-week endeavor, where large families often shared a single tub of hot water, which became progressively dirtier with each subsequent bather. Working conditions were better than in Poland, but harsh by today’s standards. Shifts of 10 hours were not uncommon, but workers generally got Sundays off.

Most Poles were employed as laborers by the big Milwaukee industrial companies of the day, including Allis Chalmers, AO Smith, Pfister & Vogel Tannery, or the many foundries and mills in the area. These were dirty, dangerous jobs and it was not uncommon for injuries and even death to occur in industrial accidents. Michal Grochowski soon went to work in Milwaukee’s knitting mills. Companies like the National Knitting Company and Phoenix Hosiery were a mainstay of Milwaukee’s Polish south side, employing hundreds of women, until they moved their operations to Georgia in the 20th century. Michal had quickly developed a command of English, which enabled him to rise to the role of floor manager at Phoenix Hosiery and, later, at National Knitting. There, he met Stanislawa (Stella) Sikora, the youngest daughter of a large Polish family from the same region of Poland.

Michal and Stanislawa were married at St. Josaphat’s on October 23rd, 1900 and Michal rented a house at 1090 6th Avenue (now S. 11th Street), where they soon started a family. By 1921, the family had six children and were living at 511 Maple Street. Many in the family were working in the knitting mills. Sadly, Michal passed away on February 27, 1931 from Pneumonia. At 56 years of age, he had reached the average life expectancy for an industrial worker of the day. Stella Sikora continued to work in the knitting mills until she retired to live with her children, passing away in 1954.

Michal Grochowski and Stanisława Sikora, October 23, 1900 (Source: author's archives)

Michal’s adoptive father, Anton Grochowski, eventually remarried following the death of Michal’s mother Magdalena, and lived to the age of 84, passing away in 1941. Michal’s half-siblings had also put down roots and soon started families of their own.

Michal’s younger brother, John Grochowski, never married, though. He worked as a riveter for the George Meyer Company on Clinton Street (now S. 1st Street.) He lived with the family of his sister Frances until his death on September 8, 1925.

Michal’s sister Frances married John Czaplewski, whose family had come to Milwaukee in 1878 from the same part of Poland. The family lived at 824 Garden Street (now S. 5th Place) and had ten children by 1925. John worked as a house painter and interior decorator while Frances raised their ten children. Frances passed away in 1928, while her husband John lived to be 87 years old, dying in 1968.

Michal’s half-brother Joseph Grochowski married Rose Kolinski and they moved in with the Czaplewski family at 824 Garden Street. Joseph worked as a machinist for Federal Rubber in Cudahy and later worked as a plumber while Rose raised their three children. Rose died in 1942 and Joseph lived until 1958.

Michal’s half-brother, Anthony, married Mary Wrycza and they settled into an apartment on Lincoln Avenue. Anthony worked as sheet metal worker for George Meyer Manufacturing along with his older brother John. Anthony and Mary had nine children and Anthony lived until 1947, while Mary lived until 1966.

Michal’s half-brother, Albert, married Agnes Schwichtenberg and the couple had three children. Albert worked as a boiler maker for the Patton Paint Company and lived until 1969, while Agnes lived until she was 89, passing away in 1983.

Michal’s half-sister, Rose, married Charles Hoppenrath and the two had a daughter. Rose eventually moved to Detroit and, later, Kenosha. She married a total of five times and lived until 1971.

Milwaukee’s Polish core developed a distinctive culture during the first half of the 20th century. Much of it revolved around the Catholic church, which occupied a central place in the community, social and spiritual life of Milwaukee’s Polish immigrants. Groups like the CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) brought young men and women together and local parish societies began important community organizing points. Large family gatherings, mostly on Sundays after church, brought together extended families to share in traditional Polish culinary delights, often prepared by teams of wives and grandmothers. Neighborhood taverns also played an important role, particularly after WWI. Nearly every neighborhood had a family run corner tavern, which often served as a gathering place for workers after a long day and for families to enjoy a Friday fish fry.

In the period after WWII, Milwaukee’s second and third generation Poles began to migrate to the suburbs, first populating the area around Oklahoma Avenue and moving out into what is now Greenfield, West Allis and Hales Corners. Most of the Milwaukee’s Poles born in the 20th century benefitted from a well-established system of Catholic parochial schools and many attended college at Catholic institutions such as Marquette University and Alverno College. Like many Milwaukee Polish families, the Grochowskis expanded exponentially in the 20th century.

Today, Anton and Magdalena Grochowski have nearly 1000 descendants, many of whom remain in the Milwaukee area. These descendants have now married and most no longer have Polish last names. They come from all walks of life and all parts of the country. Some are artists, some are CEOs of major companies, some are scientists, most are middle-class suburban Americans. I have been surprised on more than one occasion to discover, through genealogical research, that I’m related to someone I had already met through other circumstances. To get an idea of the Grochowski family’s substantial contribution to the Milwaukee cultural landscape, it is worth recognizing that Magdalena Grochowski had 35 grandchildren, 64 great grandchildren, over 200 second great grandchildren, and over 500 third great grandchildren, most of whom have started families. Magdalena Grochowski’s DNA is now detectable in well over 1000 people.

I frequently visit the old Milwaukee neighborhoods where the Grochowski family first lived and worked. Much of the area has been regentrified with popular Mexican restaurants and vibrant hipster cafes, but the old Polish flats still remain and are once again populated by large immigrant families. Many of these families came to Milwaukee from circumstances and for reasons very similar to those that brought Michal Grochowski to Milwaukee 130 years ago and many are still finding the same opportunities and optimism that fueled the Grochowski family’s American experience.