Based on the book "Bal w Hotelu Polonia", Alceo Valcini, 1983. [1]

On December 17, 1945, a train left the Termini station in Rome, which included a diplomatic carriage with inscriptions in Polish, English, German, French and Russian, which specified the destination and country of origin, and a request to respect the international diplomatic integrity of its passengers and cargo.

The newly created Polish Embassy headed by professor Stanisław Kot organized a Polish diplomatic carriage to transport a cargo of oranges and several personalities to Warsaw. Among them was the Italian journalist Alceo Valcini with his wife, who knew Poland from his previous stays.

Already in 1934, he was sent there for the first time as a foreign correspondent for the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. He was an eyewitness to the German invasion of the Polish capital in September 1939, and left Warsaw in July 1944, just before the uprising broke out. Now, after a year and a half, he was returning to the city he loved and the people he called friends.

Before his departure, many Polish officers from the Second Polish Corps commanded by General Anders came to him and gave him letters to their families they had not known anything about for over six years. One of his journalist friends, when he heard about his departure, said: “Have you started studying archeology? After all, Warsaw is just a desert of rubble."

Passengers were advised to prepare a packed lunch, which consisted of canned food, biscuits, marmalade, and dried vegetables. The Ghost Train was dispatched without any timetable as the railroad routes at the time were uncertain.

After 24 hours, the train reached Bolzano, then traveled through Brenner, Innsbruck and Kufstein in Tirol, where Austrian territory ended. The train passed Bavarian Rosenheim, then Munich and then Landshut. The city was almost empty. At the several storefronts, bread sold in exchange for food stamps, marmalade and boxes of matches could be seen. Around the railway station, there were groups of Poles who intended to return to Poland, lost Germans, Jews who wanted to emigrate to Palestine, and Italians who did not know what to do with themselves.

The train traveled via Furth to Pilsen in Western Czechoslovakia. Here, travelers had more time and went to the main square of the city. There were stalls with large, smoking pots in which sausages were cooked. They were sold for the, so-called, "leaf", a consumption voucher that travelers did not have. The next part of the journey ran through Praha to Zebrzydowice.

The travelers went to the city. To their surprise, they easily managed to buy freshly baked bread, ham, sausages and hot tea.

After breakfast, the train set off for Katowice. The travelers were given time to go out into the city. People in the streets were poorly dressed. Some carried Christmas trees under their arms. In a small shop, Valcini saw candies, chocolate bars, Christmas tree tinsel and citrus fruits at the price of 260 złoty apiece. The journalist sold a few oranges for a lower price to a satisfied shop assistant in order to get some Polish money for food. An orange and a half was enough to pay for a meal and a few vodkas at a nearby restaurant.

In Zebrzydowice, the diplomatic car was attached to a passenger train that reached Warsaw at night. The journey took seven days.

At first, travelers thought that the train stopped in the middle of nowhere. Before them was a flat space covered with a slippery layer of mud. At dawn, they waited for the outlines of houses to appear on the horizon — in vain. While taking a taxi to the Polonia Hotel, Valcini tried to see any buildings resembling Warsaw that he had left before the uprising. The view resembled a gigantic surreal painting. Persistently in his mind reverberated the sentence that Warsaw no longer exists.

In other European capitals, they were counting demolished houses; in Warsaw, remaining houses were counted. When the Soviet troops entered Warsaw on January 17, they were greeted by the silence of a dead city. It even shocked the soldiers who fought at Stalingrad.

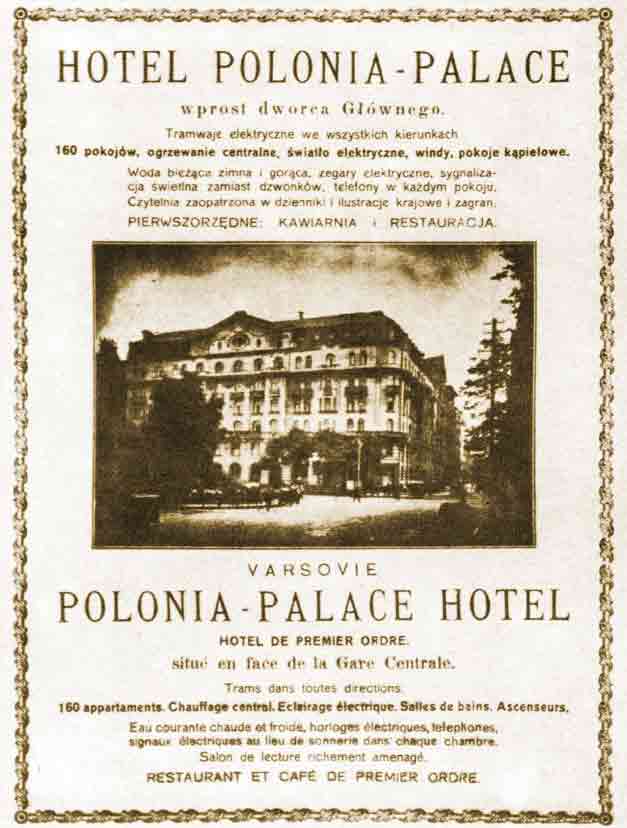

The Polonia Hotel was the only building that could be lived in and that is why it housed embassies and journalists coming from foreign countries. Some of the rooms were broken, the walls of the rooms had bullet holes, but this hotel was the only large hotel among the few buildings left in Warsaw.

"Polonia" Hotel in present times (Source: Wikipedia)

The Valcini couple were given room number 345 on the third floor with a bathroom in the hallway. The mirror in the room was broken and a bullet hole was visible in the center. During the war, this hotel was used by the soldiers of the Wehrmacht.

The hotel Polonia was inhabited by diplomats, senior UNRRA officials, employees of the International Red Cross and various delegations from various countries. They all had their own cars, chauffeurs, clerks and secretaries. They all wore uniforms to be easily recognizable to the Polish militia.

The Valcini family came to Warsaw on Christmas Eve. In accordance with the old Polish custom, the hotel staff stopped working at 6 p.m., which was a great difficulty for the guests of the hotel. It was the first Christmas Eve of free Warsaw and makeshift chapels were built in various places where the faithful prayed. Destitute crosses were visible at all street corners, at the intersections of non-existent roads, on ruined squares, and razed courtyards. Christmas tree lights could be seen in the few interiors of the surviving houses.

Advertisement from 1927 placed in Polish Restaurant and Hotel Keeper Periodical No. 9 (Source: Wikipedia)

The journalist could not believe that he saw the same Warsaw, which he remembered for the wealth of its homes, the elegance of women and brave youth who sacrificed themselves for their homeland.

The mood of the people in the destroyed capital of the defunct city was gloomy. There was hate, regret, contradiction, confusion and insecurity. Happy Holidays sounded more like a whispering complaint. People were still searching for one another. The radio was constantly broadcasting desperate calls for information.

The next day, while walking, he saw the stumps of buildings marking Marszałkowska Street, Aleje Ujazdowskie and the gigantic hull of the railway station, which was in danger of collapsing.

There were two eateries near the Polonia Hotel. One of them ran a home kitchen and was run by society ladies from the former bourgeoisie. One was called "Congo" and the other "Canaletto". In Congo, Valcini sold his remaining small stock of oranges to a landlord he knew well before the war, who was then a bank manager at Moniuszko Street.

Some diplomats did not like the menu of the Polonia Hotel and began to prepare their own meals in their rooms using electric or spirit cookers. One day the minister of the Netherlands, on an official visit to the second floor to a colleague from the Romanian Embassy, stopped when he smelled a pleasant scent of cooked food. His secretary, who accompanied him, said: "Veal cutlets with baked potatoes, Minister." "Yes, it smells good," replied the head of the mission.

The British office occupied the entire fourth floor. Early in the morning, its young diplomats ran up the stairs and into the bathroom. Others had to wait a long time, and in the corridors, you could admire the ambassadors in slippers, towels and soap in a tightly clenched hand, as they passed other mission heads while exchanging ceremonial bows.

Sometimes there were misunderstandings. One embassy sent an official letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in which it stated, that "...the ministry is forced to send a protest note to the neighboring Bulgarian Embassy, because its staff had fun all night, improvising choral singing and playing the accordeon, which disrupted the sleep of the ambassador and his wife. Physical protests involving punches against the wall separating the two countries did not bring the expected effect. After leaving his extraterritorial zone at 3:00 am and approaching the zone of the Bulgarian Embassy located in room 240 on the third floor, the ambassador knocked on the door to express his dissatisfaction. A young woman, scantily dressed, probably of Polish nationality, opened the door and tried several times to kiss him and make him drink vodka, which the representative of the republic does not like. The Bulgarian embassy staff does not pay any attention to the rightful protests of the neighbor and, in order to avoid such events in the future, asks the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to act as a mediator, so as not to disturb good relations between the given republic and Bulgaria in the hospitable Poland and, in consequence, around the world."

Source: Wikipedia

Valcini often walked around Warsaw. Sometimes it seemed to him that the city was full of euphoria, that the women on the streets looked beautiful and elegant, that the men were bold and that everyone was happy. On another day, he saw terrible ruins and people overwhelmed with sorrow and pain. People were irritable and easily exploded with anger. Proud Warsaw women looked with envy at American and English ladies who were in a privileged position.

Many Poles fled to other countries. Contrary to the appearances of normal stabilization, the post-war chaos in Poland continued. The war had only ended a few months earlier. Warsaw, especially at night, was not safe. Residents continued to fight for their lives. Trade flourished in the streets where gold was bought, dollars were sold, coupons of fabric, American and English cigarettes were sold. The sellers were people of all professions - intellectuals, teachers, former students, servants and common criminals. Goods were sold that came in parcels as gifts from the west and then ended up on the black market. The militia tried in vain to eliminate it. The lands abandoned by the Germans in the West attracted merchants, but even ordinary people went there to bring home some furniture and necessities.

There seemed to be no living conditions in such a city. The foreigners who lived at the Polonia Hotel were amazed that Poles can sometimes be so carefree and laugh at the terror of a ruined city and graves in streets and squares.

And yet the inhabitants populated the ruins and proved Hitler's cruel predictions a lie. Warsaw was returning to life. At the site of the formerly elegant streets, the city grew at the level of the first floor. Demolished buildings were turned into shops. The most enterprising were representatives of the bourgeoisie and the wives of officers who remained in Western Europe. Their daughters worked as waitresses, following the example of actresses during the occupation, and others were saleswomen in the stores that opened first.

The population in Warsaw continued to increase despite difficulties in finding a roof over their heads. Varsovians returned to the city from all corners of the country, despite the prohibition of the authorities. It was not known yet whether the capital would be worth rebuilding, but it was decided to revive it by a government decree. The supply and sanitation difficulties were enormous. The constant influx of people threatened to paralyze life in the city. There was a shortage of funds and foreign subsidies were small.

In the first months of 1946, supplies deteriorated considerably and the government issued a decree that prohibited serving meat meals in restaurants three days a week: Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. This was due to the decline in the cattle stock and poorly functioning transportation. The black market, however, quickly overcame this situation and in almost every restaurant you could get a meat dish, disguised with a cabbage leaf on top.

Contrasts became more and more visible. A large part of the inhabitants lived in cruel poverty, and at the same time luxury flourished in new shops in one-story buildings. Foreign diplomats were surprised that such a large amount of various goods was in stores.

Poland experienced a difficult period at the turn of 1945 and 1946. The Yalta accord placed it in the Soviet sphere of influence, which was to be confirmed by the people through "universal, free and secret" voting. The task of the American and British diplomats was to ensure that the voting was conducted correctly. The government in Lublin was transforming the country politically and ideologically. Western citizens have become uncomfortable persons who could impair the official propaganda. An auxiliary militia body ORMO was established in Poland. During the day, on the street corners around the Hotel Polonia stood Soviet soldiers wearing armbands of the military militia, with machine guns slung across their chests. They did not accost anyone and tried their best to be invisible.

One day, the diplomats saw women on each floor of the hotel, allegedly giving answers and fulfilling guests' requests. In fact, they watched who came in and out of the rooms and they took notes. There was a tension in the city. A friend of the journalist at the Polonia hotel said quietly to him: “If all else fails, we'll start all over again. There are enough weapons around."

When Valcini arrived in Warsaw, there were only six foreign correspondents: Marshall from France, Allen from the USA, Englishman Selby, Cang from Manchester Guardian, and a representative of Czechoslovakia. In addition, there was a group of journalists, guests of the government, and representatives of several magazines: Bloom from Johannesburg, Piniewski from Detroit, Molski - a correspondent for "The Protestant", an Indian from Madras, and a Dannish woman, a staunch supporter of Marxism. The most informed of the correspondents was the American Allen, and among the diplomats it was the Czechoslovakian ambassador Józef Hejret.

At that time, there was also a certain Belgian diplomat in Warsaw with his friend who, sent by a large company from Brussels, wanted to recover the huge capital invested in Poland before the war. He rarely left the hotel, but was oddly knowledgable about everything.

Three important dailies were published: Głos Ludu (The Voice of the People), Wieczór Warszawy (Warsaw's Evening) — both pro-government, and the opposition newspaper, Gazeta Ludowa (The Peoples' Newspaper). The paper allocation for the latter was so small that the editors urged readers to pass it on to others after reading it.

Foreign diplomats asked themselves what happened to the Polish aristocracy. Gradually, information about it began to flow in. One of the descendants of Count Józef Tyszkiewicz was shot by the Gestapo in Warsaw. The last descendant of the Walewski family, the count, died during the uprising. The leader of the Warsaw Insurgents, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, was a count and was arrested by the Germans. The outbreak of the war found the Radziwiłł family in the eastern part of Poland. They were imprisoned by the Russians and sent to Moscow, but Stalin released them as a result of the intervention of the British court and the House of Savoy. Prince Lubomirski and Count Przeździecki took important positions in the diplomacy of Józef Beck, the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Prince Janusz Radziwiłł personally intervened with Marshal Goering to release the professors of the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. He himself and his wife were arrested during the Warsaw Uprising, but later returned to the capital. His son Stanisław, the husband Jacqueline Kennedy's sister, offered him years of prosperity in America, but he refused. Polish nobility - Radziwiłł, Czartoryski, Lubomirski, Zamoyski, Branicki, Sapieha, and Sanguszko no longer had palaces, hundreds of thousands of hectares of land, or private troops.

Most of the beautiful palaces in Warsaw were demolished by the Germans during the Warsaw Uprising. The Radziwiłł Palace at Bielańska Street has now been transformed into the Lenin Museum. Ignacy Potocki fought in the ranks of partisans in the forests on the San River. After the end of the war, he was unable to find a job for a long time and became a truck driver. Before the war, he participated in the memorable 14,000 km rally in Africa. Only much later did he find a more responsible job. After leaving the palace in Jabłonna, Maurycy Potocki went abroad to London. Barbara Czartoryska became a doctor of biochemistry. The aristocrats started teaching English and French in middle schools. A countess was a newslady in the corridor of the Polonia Hotel, and her nephew Stanisław was employed as a chauffeur there. Włodzimierz Czartoryski worked as a bookbinder. Beata Tyszkiewicz became a film actress. Gradually, Polish aristocrats blended into the composition of Polish society as well as others. Włodzimierz Czartoryski worked as a bookbinder. Beata Tyszkiewicz became a film actress. Gradually, Polish aristocrats blended into the mainstream of the Polish society, on par with others.

In March 1946, it was decided to organize a ball for the charity of the Polish Red Cross at the Polonia Hotel. The Committee of Polish Ladies was to give the evening an international character. Corridors, cafes and restaurants were turned into one large lounge. An orchestra and a buffet were organized. On the part of the diplomats, a certain number of bottles of fine wine, liqueur and classic whiskey were delivered for free, which arrived in Poland by diplomatic mail. Crates of fine wine bottles from the smugglers' secret lockers were transported to the hotel. The Polish government authorities were not invited so that it would not be necessary to apply the diplomatic protocol. It was supposed to be a step towards normalizing life.

Contemporary look at the Hotel "Polonia" lobby (Source: Wikipedia)

Most of the diplomats were men, so it was decided to invite Polish women to join the company. The news about the ball spread throughout the city. Residents tried to get invitations, although they blushed to ask about the price. Mothers wanted their daughters to get to know the upper spheres. They came to the hotel wanting to talk to the diplomats. Daughters also ran upstairs and knocked on any room door, interrupting the work of diplomats. Beautiful, smiling girls peeked through the doors and announced that they had come with regards to the ball. After five years of sacrifice, they wanted to find themselves in this fabulous world, even for a short time.

At the meeting of the heads of diplomatic missions, it was decided that the gentlemen would not wear tuxedos, so as not to embarrass the Polish guests, but dark suits. The ladies, on the other hand, were told not to wear expensive dresses that Polish women could not have.

The ball started on time and the orchestra played fashionable pieces - tangos, waltzes and foxtrots.

The foreigner women watched the Polish women with interest. With great surprise they saw the women who came out of the demolished houses, dressed elegantly and with great taste. They looked like princesses awakened from sleep. They appeared in silk slippers, after checking in their shoes to the coatroom. They overcame the difficulties of finding good fabrics in an extraordinary way. They made dresses of velvet, lace, and silk and decorated them with colorful beads. At the sight of such elegance, the wives of diplomats looked angrily at their husbands, who ordered them to dress modestly. One foreign woman ran to her room and after a while went down in an elegant evening dress. Full of astonishment, the foreign guests admired the enthusiasm with which Poles danced when the orchestra played mazurkas, obereks, krakowiaks and traditional polonaises.

After the dancing, a hot, tasty bigos (hunter's stew) was served as a surprise.

During the last crazy nights in the "Adria" restaurant before the war, the famous piece lambeth-walk was played and this piece was played by the orchestra as a farewell.

Some diplomats discreetly began visiting antique stores. There were remnants found miraculously under the demolished houses of aristocrats. People got rid of these things to buy food. People who traded in goods attractive to foreigners appeared at the hotel. One delegation, staying briefly in Warsaw, upon return, had trouble taking off in a small plane because it was overloaded with silver antiques.

Every day, long rows of trucks and village wagons bringing new residents entered Warsaw. At that time, the city had a population of over 400,000.

The capital city seemed cleaner and tidier in the spring. With great dedication, the inhabitants of Warsaw cleared the city from rubble. The arteries were cleared of debris and the crosses were removed from the streets. People visited each other among the ruins, and flowers were visible behind the shop windows. The girls and boys began gaze at each other with interest again. Theaters and small scenes gathered poets, writers and singers. Literary cabarets began to operate.

On January 17, the Theater of Poland (Teatr Polski) reopened with the staging of Juliusz Słowacki's drama "Lilla Weneda". The inauguration of the opening of the rebuilt National Museum took place. At the entrance, Nazi flags were placed on the marble steps so that visitors would trample them upon entering.

Diplomats, who were about to end their stay in Poland and who, at first, could not imagine living in a country where you still had to be careful not to trip over a stone from a demolished house, suddenly became sad. They got used to the hardships they had to overcome every day. They were touched by the turbulent fate of Warsaw. They saw the arduous work of the Varsovians, which they were performing in silence while rebuilding the city. They were sent here to inform their countries about the politics and mood of the population, but they could not resist the charm of the Poles. Some of them returned to their countries with Polish wives. Whether they were the ones who knocked on their door with smiling faces and announced that they had come with regards to the ball, it is not known.

Friendly relations forge between the representatives of the East and the West at the Polonia Hotel. The farewell banquets were an occasion for cordial meetings. Gradually, the number of diplomats and journalists in the hotel began to decline. They returned to their countries. The newly arrived young officials did not understand the situation of Poland at all. They brought with them pre-war Bedeckers [tourist guides] and on their basis they searched for streets and monuments. They asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs when the hunt for the capercaillie, lynx, wild white hare and wolves would begin. More and more diplomatic missions moved to other buildings in Warsaw. Valcini and his wife also left the capital at that time. As he wrote later, he felt like a traitor.

In the spring of 1947, strange birds appeared in Warsaw, never seen there before. The townspeople looked at them in disbelief. They had a grayish color of feathers, long tails and rather large beaks, but they did not resemble birds of prey. As they flew from tree to tree, their wings spread wide. The summoned ornithologists could not answer what species they belonged to. Later, these birds mysteriously disappeared and never again re-appeared.

Later, the inhabitants were saying that these were mud birds, which saw Warsaw as a vast swamp while passing by...

The Polonia Palace Hotel is a historic, four-star hotel opened in 1913, located in the heart of Warsaw at Aleje Jerozolimskie. It is the second oldest hotel in the capital, after the Bristol Hotel. Together with the neighboring Hotel Metropol and Hotel MDM, it is managed by Grupa Hotelowa Syrena. It was recognized as a monument of architecture, history and culture of Poland on July 1, 1965.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.