In the 1930s, the Warner Brothers film studio produced films in the spirit of social realism, covering less appealing themes in modern America, such as crime, poverty, and a clumsy legal system. In these films, Poles were presented as criminals and negative characters. In one of those films, The Life of Jimmy Dolan, the evil character was called Pulaski. In another film, How Many More Knights, a gangster and murderer was a man named Kościuszko.

The Polish Ministry of the Interior protested, saying that “the names of Pułaski and Kościuszko are dear to every Pole and American film producers should be aware of this. Since they are not, the Polish government has decided to ban the screening of not only these two films, but any other films produced by Warner Brothers and two other studios. Warsaw believed that Warner Brothers were to blame for tarnishing the honor of the Polish nation and were conducting anti-Polish propaganda." Harry Warner, head of the studio, described the reaction of the Polish government as anti-Semitic. Nevertheless, the studio shot new scenes for the film and later apologized to the Polish government.

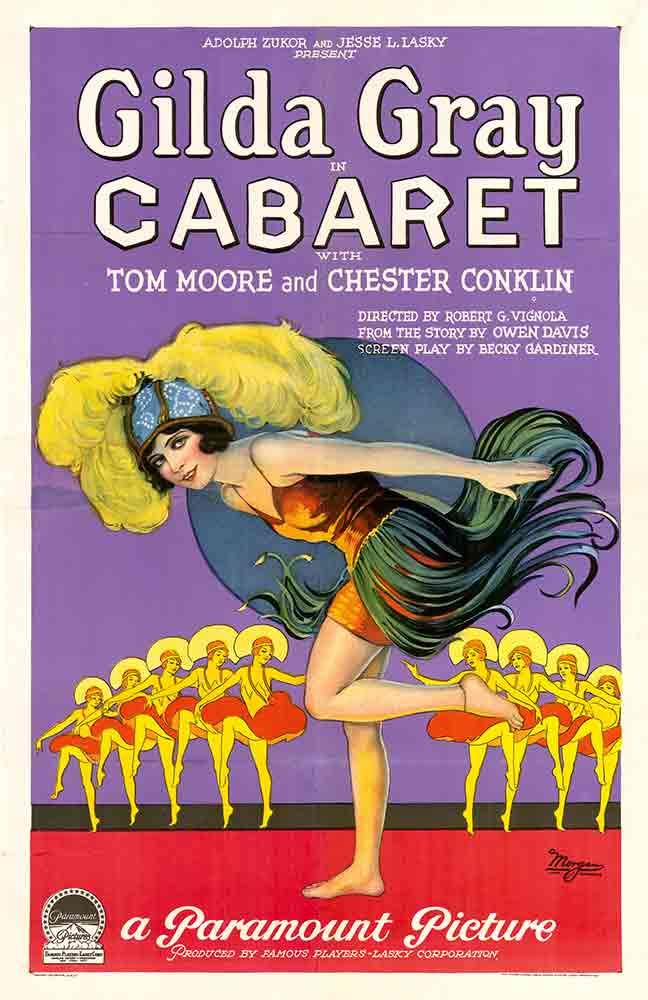

During the silent cinema period, several Polish actors achieved great success in Hollywood, albeit short-lived. Almost none of them revealed their Polish origins. Marianna Michalska and Apolonia Chałupiec, both born in Poland, were stars of silent cinema, appearing under the pseudonyms Gilda Gray and Pola Negri.

Actress Gilda Gray with Chester Dziadulewicz, manager of the Kuryer Publishing Company (Source: Wikipedia)

Gilda Gray starred in several movies in the 1920's. Unfortunately, she suffered a heart attack and made her last film in 1936. During World War II, she devoted herself to the Polish cause and raised funds to help Poles, and often came to Milwaukee, being in close relations with the Polish Kuryer.

The patriot Pola Negri, strongly associated with the Polish community, laid a wreath in 1923, five years after Poland regained independence, at the Kosciuszko monument in Chicago. She then said, “I have not come here to collect applause or fortune, but to bring fame to our people. I want to contribute, albeit slightly, to the glorification of our reborn, beloved homeland”. Later, she was a donor to the Polish Roman Catholic parish in Texas. In the 1930s, she refused to appear in a German film because she thought it would be a disgrace to Poland. For a short time, she was the highest-paid actress in Hollywood. Never before or after has any one in Hollywood gained such popularity and influence, while being devoted to the Polish community. Her career in Hollywood ended in the 1930's.

Estelle Clarke (Stanisława Zwolińska), born in Warsaw, had a short career. She played larger roles in ten films between 1924 and 1928, but her career ended when she was only 29 years old.

Estelle Clarke/Stanisława Zwolińska (Source: Wikipedia)

The opera singer Jan Kiepura also became a film actor in Hollywood. He had a beautiful, tenor voice and undeniable charm, but he was stiff on stage and knew little English. He was mainly portrayed as an Italian. After the outbreak of World War II, he often sang Polish patriotic songs during his performances, wanting to draw the attention of the American audience to the fate of Poland. The American public, however, knew him very little.

Undoubtedly, the greatest success of all American Poles was Tom Tyler, born Wincenty Markowski in a small village near New York. He was a handsome man of titanic strength, a boxer and an Olympic weightlifter. He has starred in over 200 films, often playing cowboy, and was almost always given an Irish name. However, he was poorly paid. Due to illness, he ceased to perform. Ironically, he became very popular shortly before his death. Old films with his participation began to appear on television frequently. Unfortunately, he didn't obtain any financial gain from it, as he didn't buy the rights to his old films. For a short time he was an idol of the audience, but no one knew about his Polish origins.

At the end of the 1930s, Michał Mazurkiewicz from Tarnopol began a long career in Hollywood, playing bandits and criminals. The great professional wrestler played under the name of Mike Mazurki for many companies until his death in 1990. Despite being cast in these kinds of roles, he was a highly educated intellectual. He was never identified as a Pole, which was allegedly related to the territorial changes of Polish borders after the Second World War.

American public opinion generally showed little interest in Poland in the interwar period. The left hated Poles for their victory over communist Russia in the Battle of Warsaw in 1920. Moscow regarded Poland as a reactionary country and a threat. Ignoring and minimizing the importance of Poland was a common goal of various interest groups in America. These were strong forces that tried to prevent creating a good image of Poland. The majority of the Polish community in America was materially poor and relatively powerless. The Catholic Church in America was dominated by the Irish, who saw Poles as rivals in church domination and hierarchy, and at best as naive newcomers who could be easily manipulated in politics and religion. At the same time, Poles felt a strong pressure to assimilate into the American environment,

Before 1939, one almost never heard about Poles, whether among actors, or film directors. The few were practically invisible, used changed names, and avoided any contact with the Polish community. The rule in American film at that time was to avoid Polish topics. Hollywood's brief interest in America's ethnic mosaic declined sharply before 1939, when the emphasis was on national unity in the face of external threats. Poles began to be called Eastern Europeans (Poland is in Central Europe) or Slavs.

On the part of the American government, it was not caused by anti-Polish prejudices, but by the need to protect Soviet interests. The Roosevelt administration considered Poland's participation in World War II to be insignificant, while the promotion of Moscow was very important to it. Close cooperation with Stalin was the basis of the war strategy and the foundation for the creation of the post-war world. Any public discussion of the Soviets' actions towards Poles was not well received. A government agency monitored the film industry and eagerly ensured that Russia be presented in a positive light. In this approach, the subject of Poland was watched particularly closely.

After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the American community sympathized with the Poles, but Poland was far away and was in the sphere of the Americans' marginal interests. Only after 1941, when the Soviet Union entered the war against Germany, the situation changed. Support for the Russians has increased sharply, and also for their political and territorial plans for Poland.

The popular portrait of Poland began to be destroyed. The American historian Richard C. Lucas notes that the most significant phenomenon of the Second World War was the dramatic change in the American approach to the Soviets and Poles. At the end of the war, the Soviets were an admired and respected nation, while Poland was characterized as "an enfant terrible, threatening to destroy the Allied alliance with Russia."

This situation worsened even more in 1943, when the Germans discovered thousands of Polish bodies in Katyn on the Eastern Front. The Russians who perpetrated this crime accused the Germans of having committed them. The American community mostly shared the Russians' view. Poles who knew the truth became isolated in their opinions. For many, the Poles who were not accepting of the German guilt, were perceived as wanting to destroy the US-Soviet friendship. When the Russians severed relations with the Polish government shortly thereafter, American public opinion blamed the Poles for this state of affairs.

Between 1939 and 1945, Hollywood released about 500 films a year. 74% of the country's population went to the cinema at least once a week. The manipulative content of the films shaped the opinion and attitude towards the government's actions. Film has become a means of education for the masses. A huge number of these films were wholly or partly devoted to the war. Almost none of them concerned Poland.

It would seem that it is precisely Poland that should be presented as an example of the barbarity of the Germans who wanted to conquer the whole world, and the Polish military campaign as a testimony of sacrifice and heroism. Hollywood, however, did not pay attention to Poland until 1942, when he produced the single, controversial film To Be or Not to Be. The film was a form of political satire and black humor.

Only two years later, in 1944, two low-budget films about Poland were released. These were In Our Time and None Shall Escape. The first film was about two English women traveling through Poland before the war. One of them marries a Polish count and their story shortly after the outbreak of the war is told. The second film, although it was produced during the war, concerns the trial in Nuremberg over the German Nazi. These were the last "Polish" American films from the war period.

By comparison, Norway, whose military resistance against Germany in 1940 was short, and whose regime under Vidkun Quisling collaborated with Germany, has been the subject of endless attention from Hollywood. Norway has been the subject of a lot of Hollywood-starred movies, and has enjoyed significant financing. France has also been the subject of widespread attention by American film producers. France has become a symbol of freedom in chains. Unlike Poland, the French defense was unexpectedly short. The Vichy government, led by Marshal Petain, collaborated with Germany, and French troops did not fire a single round during the US Torch landing operation in North Africa in November 1942. Czechoslovakia was another country with at least six films. They were all sympathetic to the Czechs, despite the fact that this country did not oppose the German occupation either. The Czech Victor Laszlo in the movie "Casablanca" became the most famous fighter in the history of Hollywood.

In this way, the war was presented to American viewers through the experiences of Norwegians, French and Czechs. Hollywood decided to omit Poland from its films during the war.

The extraordinary growth of popular Russophilia was also expressed in the growth of pro-Soviet films. The 1943 film "Mission to Moscow" caused an enthusiastic mood. Americans became immensely friendly to the Soviet Union during this period, and undoubtedly Hollywood played a part in that. It became a willing helper for Russia in portraying Poland as a reactionary obstacle to Soviet-American cooperation. Communist screenwriters portrayed the anti-fascist march of the Russian army, and Poland as a fascist state that opposed Russian territorial plans and Russian independence.

Part of the Hollywood community, namely directors and screenwriters during the Second World War, were Jewish immigrants or their children. Many Polish Jews were among them. However, they never identified with Poland or revealed their Polish origins. The influence of these directors on the content of the films was very significant. Any complaints from Poles meant very little. At the same time, the vast majority of Americans did not understand the accusations levied by the Poles. The most important thing, however, was that the Hollywood Jewish community classified Poles' complaints as anti-Semitic, so they were being immediately rejected.

The cover of the 2010 book by M. Biskupski (Fair use)

The most relentless source of anti-Polish propaganda during the war in Hollywood was the Warner Brothers Studio. It was responsible for producing such films as In Our Time, Action in the North Atlantic, Air Force, and Edge of Darkness.

The Warner brothers were of Polish origin. Their parents were born at the end of the 19th century in the village of Krasnosielc in Mazovia, about 80 km north of Warsaw, at a time when this part of Poland was under Russian rule. In 1937, Forbes magazine described the head of this family's descendant as a Polish peasant who emigrated in 1883 in search of religious freedom.

In fact, Ben Warner (surname assumed in Canada or USA) was a shoemaker and he and his wife Pearl Eichelbaum first emigrated to Ontario, Canada, where their most famous son Jack was born, and then settled in Youngstown, Ohio. Jack Warner, in his memoirs, described the poverty and primitive living conditions of his parents before his departure.

The Warner brothers were frequent visitors to the White House during the war to meet with Roosevelt. Jack Warner described the production of pro-Soviet films such as Mission to Moscow and Air Force as morally inspiring. The brothers believed that they were contributing to the war effort.

In October 1947, a frightened Jack Warner appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and tried to convince the court of his support for the fight against communism. He stated to the committee that the films produced during the war had virtually no meaning and that he did not know whether their ideological content was correct. He was using the lack of recollection as an excuse when the commission asked him why he made the film Mission to Moscow in 1943, which strongly sympathized with the Stalin regime. He stated that he had never been to Russia so he could not know how to present it correctly.

Today, numerous, detailed documentaries about the Second World War, shown on television around the world, also omit Polish topics. The only narrative in these films about Poland is the information about the outbreak of the war on September 1, 1939 and the subject of the Auschwitz extermination camp.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.