At the joint meeting of the Main Board of the Supreme Council and the Audit Committee of the Union of Poles in Germany (ZPwN, Związek Polaków w Niemczech) on August 24, 2004 in Göttingen, 6 demands were made against the German government. Here they are:

- Polish organizations in Germany do not receive any institutional support from the federal government, federal states or municipalities. To ensure the proper functioning of these organizations, we demand that the issue of institutional financing of Polish organizations in Germany be clearly regulated on the same terms as the Republic of Poland finances the German minority in Poland.

- We demand compensation for the property of the Union of Poles in Germany, stolen in 1940.

- We demand financing of teaching Polish as a mother tongue in public and private schools as well as schools run by associations and other non-governmental organizations wherever a demand is submitted, on the same terms as the Republic of Poland finances teaching German for the German minority in Poland.

- We demand the ratification of the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of 1995 and the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages of 1992 in relation to the Polish minority in Germany and the implementation of the Polish-German Treaty of 1991 by the Federal Republic of Germany.

- We demand that the German state ensure unlimited access to the media for Polish organizations in Germany.

- We demand that Poles in Germany be restored to the status of a national minority.

It must be said that these six postulates are the essence of the spirit, goals and ideas of the Union of Poles in Germany. Particularly painful topics — such as the demand for the return of plundered union property owned by the Federal Republic as a successor to the Third Reich, or the recognition of the status of a national minority lost in 1940 — were expressed very clearly and convincingly here. Unfortunately, to this day, the Union has not received any response to these demands. A comparison to the fate of the letter from Polish bishops to German bishops from 1965 ("We forgive and ask for forgiveness") comes to mind, to which there has been no reaction from German bishops to this day. No reaction — is also a form of response.

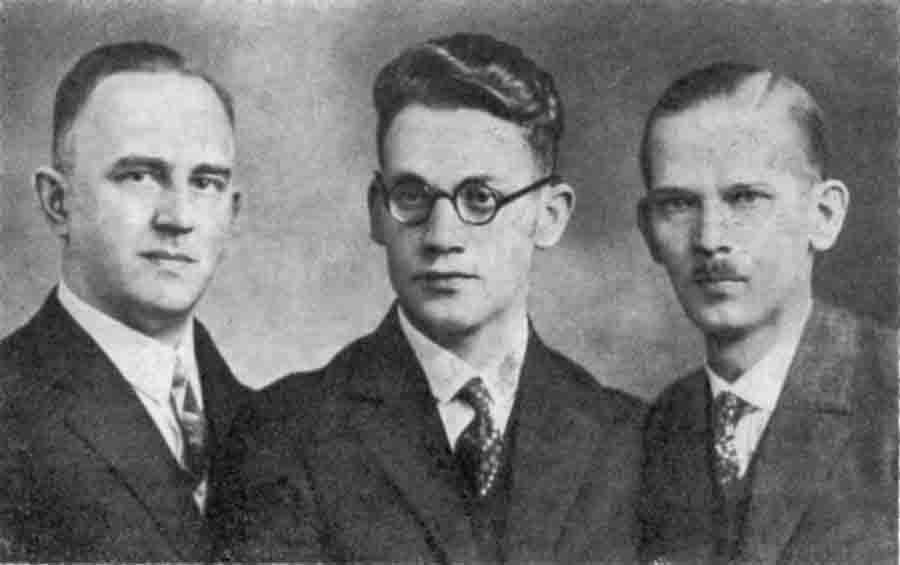

The leaders of ZPwN: Stefan Szczepaniak, Jan Kaczmarek i Józef Michałek, 1938

(Source: ipn.gov.pl)

Even the German side notices that the unsolved problem of minorities, status, seizure of property and other ills of Poles in Germany are an "unhealed wound". You can find out about it by reading the course of the meeting of the German Bundestag on August 13, 2013, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of signing the famous treaty in 1991. (2)

It is amazing that Gregor Gysi, from the parliamentary Party of the European Left, asked questions, one could say, on behalf of Poles and related to the Polish problem. He mentioned almost all the shortcomings of the German government towards Poland. It was, among others, about the "compensation for German citizens of Polish origin for persecution during the period of National Socialism." Gysi asked the government: "Does the Federal Government think that with the creation of the «Center for the Documentation of the History and Culture of Poles in Germany», which the German Bundestag has supported in a resolution «Germany and Poland – Historical Responsibility, the Future in Europe» (Bundestag document 17/6145) is the rehabilitation of the Polish minority complete?" The fact that it is not finished — the Poles and the Union of Poles in Germany are well aware of.

Referring to the lack of full rehabilitation of Poles as victims, Gysi asked: "Does the Federal Government intend to take legal or other measures to provide the above-mentioned group of people and their family members not only with moral rehabilitation, but also material compensation for periods of imprisonment and persecution?" The German Government considers that the creation of a documentation center is already "rehabilitation".

Or: "How does the federal government intend to deal with this property in the future, which was essentially stolen from Polish organizations by the Nazi state?" And these questions — like the demands made by the Union of Poles in Germany — remain unanswered to this day from the German government circles.

So it seems that in order to obtain the status, the Union and, above all, its president, Josef Malinowski, still has to demand, write, fail to miss any opportunity. Knowing his enthusiasm, knowledge of the matter at hand, and – above all – tenacity, you can believe that he will achieve it. After all, he said: "The Union of Poles in Germany is entering a new, historical stage." In an interview for Radio Poznań on June 25, 2021, he said “if we were to receive this statute again, we would have federal funds and we could conduct our activities differently; this has not been resolved to this day, but we will fight for it intently”.

It is good that the government of the United Right is supporting this fight. Josef Malinowski notices the effects of "good change", saying: "We are very grateful that Polish diplomacy helps us and puts out pressure in this regard, because this is an amazing difference, because our social and Polish diaspora organizations do not have any support. It is not only about learning Polish, but also about the very functioning of these organizations."

On October 27, 2017, the Polish Sejm adopted a resolution supporting the postulate of granting national minority rights to Poles living in Germany. This resolution is of a political nature and is an act of support for the Union of Poles in Germany, which fights for the recognition of rights. Actually, it is about restoring this right, which was seized in 1940 by the Third Reich. Documents and law from that time are in force until today, which is actually a strange thing — everyone who touches on this topic knows this.

In the last days of September, it was possible to see that the government of the Republic of Poland does not take its eyes off the unresolved problems in mutual Polish-German relations. Gazeta DoRzeczy, from September 11 this year, quotes the Prime Minister's statement to the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in which M. Morawiecki spoke, among others, on the reform of the judiciary, and also uttered a sentence that is very important for the Union: “We observe shortcomings when it comes to teaching Polish, the status of a minority for Poles living in Germany that was taken away during the Nazi era. We would expect changes in these matters." This raises hopes that the Polish government is not forgetting about Poles in Germany and that the restoration of minority rights is as relevant today as never before.

The issue of teaching Polish is also an unresolved topic. Jozef Malinowski cares not only about teaching Polish in German schools, but most of all about developing a strategy for teaching Polish as a mother tongue. Since July 2012, the Polish-German Committee for Education has been dealing with it, as well as the Working Group established by the German side, which has already held two meetings, whose chairman sits at the Polish-German Round Table.

There are still many obstacles to overcome before the Association and its President. Let the text of September 3 this year in Deutschlandfunk prove it, where you can find a commentary on the topic "Why Poles want the status of a minority" (5). It is not optimistic. Not only does the author (Melanie Longerich) see the ruling PiS party as a "motor" encouraging to fight for the status: "Since the power in Poland was again taken over by the national-conservative party PiS, they are again demanding recognition of Poles in Germany as a national minority" — she also quotes a statement by a young man, a 43-year-old resident of Dortmund (the name known to the author of this text), who was supposed to express himself as follows: "Demanding the status of a minority is an outdated maneuver on the part of the Polish government in order to salt the open wounds of [Polish-German] relations even more". By the way, Ms Longerich does not ignore the position of Józef Malinowski, emphasizing his critical attitude to the Polish-German friendship treaty of 1991 and mentions that Malinowski: "thinks it is good that the government in Warsaw, once again, supports his association more strongly."

In sum, the article in Deutschlandfunk shows how difficult the situation of the Union of Poles in Germany is, what obstacles stand in the way that the Union (and Józef Malinowski) chose, if there are official statements — whether or not from government circles, but still — statements about the lack of legal grounds to recognize Poles as a minority, because: "the Polish-speaking group in Germany does not have the status of a national minority in the light of formal law, because it is not one of the traditional minorities living in Germany, but consists of migrants" (according to Longerich).

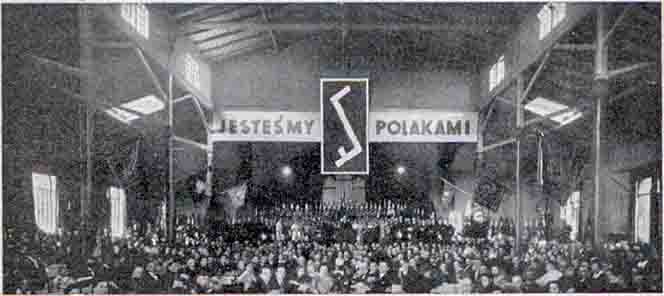

Congres of the Union of Poles in Germany, 1938 (Source: Facebook)

If the German side calls Poles living in Germany "a Polish-speaking group that consists of migrants," it is very easy to stick to the decision of not recognizing them as a national minority. The problem lies in the definition of the word "minority".

In Germany, a group is considered a national minority if it meets the following criteria: their relatives are German citizens, they are distinguished by their own language, culture, and history, they want to keep their own identity, it is traditionally native to Germany, and lives in Germany where their ancestors settled. Poles are excluded under these conditions.

Thus, since there is no generally accepted definition of "minority" under international law, it is up to each country to determine which groups are officially recognized as minorities and which are not. However, if it is assumed that a national minority is a group of people living in the territory of a given country, differing from the majority of society in terms of language, culture, ethnic origin or religion — Poles in Germany meet these conditions.

Former deputy minister of the German Interior Ministry Christian Berger admits (from the film by Andrzej Dziedzic titled In Minority Strength) that "the liquidation of [minority status] by the Nazis was against the law." But it was "a minority living in the territories of the German state, which today no longer exists in the form of that time." There is also no "indigenous, long-lived Polish minority," points out Berger. And further: "The German state has the right to define a national minority."

The secretary of state for Integration and Social Affairs in the German Ministry of Labor (2013-2017), Torsten Klute from the SPD, sees other "obstacles": "From a legal point of view, it will not be possible [to restore the status, -auth.], there are no areas of settlement of Polish ancestors in today's Germany, or if the term «settlement» is extended to «ancestral» and refers to the times of the so-called Poles of the Ruhr, in this case there are very few who would still call themselves Poles." (8)

Andrzej Dziedzic speaks about the restoration of the status in the above-mentioned film. He emphasizes that "in the event of regaining the status of a national minority, Poles would feel even better in Germany, and the German state would benefit from it".

And the German state has been benefitting. There are many positive opinions in the German media about Poles living here and their contribution to the socio-economic development of Germany. Deutsche Welle in the article: "Report on the German Polish Diaspora. The Story of a True Success" writes: "Poles are above average well educated, hardworking and well integrated — according to the latest research." (6).

The already-mentioned Torsten Klute from the SPD (appointed by the German government as the representative of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia for Polonia) said: "The integration of people of Polish origin in North Rhine-Westphalia is a story of real success", and "The level of integration of people of Polish origin (... ) is above average. It indicates the high level of education and professional qualifications of people of Polish origin, both those who came from Poland and those who were already born in Germany”.

Dziennik Berliński (Berlin Daily), the main newspaper of the Polish minority in Germany, 1938

(Source: Facebook)

This was also the goal set by the Association's President, who in an interview with Deutsche Welle (July 16, 2013) drew a contemporary portrait of a Pole, corresponding to the characteristics described by Torsten Klute. Jozef Malinowski uttered the following words: “There is a struggle to change the image of a Pole in Germany. A Pole is no longer a car thief. Now we can also see the diligence, good quality of work of Poles, as well as the political, social and economic successes of our motherland, Poland. This image is therefore better and the Union as an organization wants to perpetuate it."

So the question arises: if the social status of Poles in Germany is ascending, why is the restoration of the minority status faced with such resistance?

Translation from Polish: Andrew Woźniewicz.