Polish story, Polish performance, Polish success. The series 'Wielka woda' has delighted Netflix viewers around the world. Other indigenous productions on this platform are not far behind it. A high wave of Polish series is coming.

A quarter of a century after the flood of the millennium that engulfed Lower Silesia in the summer of 1997, two filmmakers, Jan Holoubek (son of Gustaw) and Bartłomiej Ignaciuk, made a series for Netflix that is in no way inferior to the world's best. The series was liked in one hundred and eighty countries. In the first week after its premiere alone, viewers devoted more than four and a half million hours to watching 'Wielka woda' (Great Water). The series thus ranked as high as second — in terms of viewing — worldwide in the category of non-English language productions.

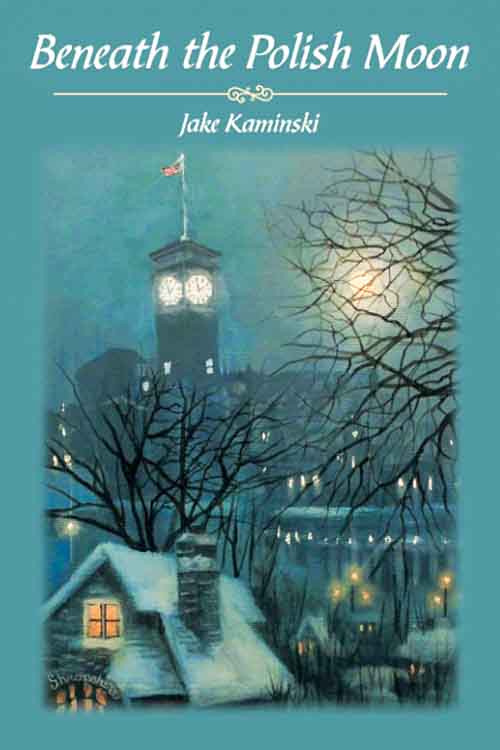

A still from the series "Wielka woda" (Source: Netflix)

The success of 'Wielka woda' lies in three strengths. First and foremost, the big money and global momentum are on display. For the purposes of the film set, Więckowski Street in Wroclaw was copied at a 1-1 scale, submerged in a kind of swimming pool. It was reminiscent of the model of the interior of the 'Titanic' filled with water in James Cameron's Oscar-winning super-production, which, incidentally, was filmed in 1997, when Wroclaw was flooded. The flood was filmed simultaneously with several cameras, including those equipped with drones constantly flying over the action location. Dozens of stuntmen and hundreds of extras performed alongside the actors. The producers took care of every detail, not only in the foreground but also in the background, in the third and tenth sets. There has not been such momentum in a Polish film since the filming of 'Ogniem i mieczem' ['With Fire and Sword'] (1999) by Jerzy Hoffman. But the preparations for the series also took more than four years. All in all, 'Wielka woda’ is the most expensive and expansive, most effective and impressive production in the entire history of Polish cinema.

A still from the series "Wielka woda" (Source: Netflix)

The second strength of the series was to convince viewers that they were not watching a story invented at the scriptwriter's desk but an authentic story firmly rooted in the realities of Poland at the time. A country that was then struggling with the half-century-old legacy of post-communism, where a sense of responsibility for one's affairs was just germinating. Until then, in similar situations, people were bailed out by the 'state', which always failed. This has not changed much. Administrators and the military have maps from several decades ago, long out of date. Floodplains that were supposed to serve as reservoirs have turned into towns, settlements and villages. The embankments, which were not tamped down for a long time, now serve as recreational and walking areas. Lower Silesia is asking for a tragedy. But the film is also fiery praise of human determination, which manifests itself in the piling up of sandbags on the embankments without regard for the time of day or night, one's fatigue, weather or hunger. A determination whose second wave has only come in our days, in spontaneous grassroots aid to the Ukrainians.

And the third asset. The series has all the essential features of a disaster film. So here we have a looming threat that both the authorities and ordinary people seem illusory, distant, improbable, and possible only in cinema. Meanwhile, we hear the warnings of specialists who accurately predict the scale of the threat, although their opinions are ignored. It is simply inconceivable to anyone that Wroclaw, a European city of almost one million inhabitants, could disappear underwater. Especially as this has not happened so far. So when the decision is taken to flood a small village and thus create a reservoir to save the town, its inhabitants instinctively revolt. And local politicians sniff out an opportunity to score some points. And then there are the dramatic scenes in which, for example, hospital staff rush to save patients as the water floods the hospital basement and rises higher and higher. So, like in a good disaster film, we have the heroism of ordinary people, the cynicism of decision-makers and the operativeness of professionals.

A still from the series "Wielka woda" (Source: Netflix)

And then there are the heartrending tragedies as people in a flooded city search for their loved ones, full of the worst premonitions of their fate. This tragedy breaks through in the fates of ordinary people placed in extraordinary situations. Thus, we have a civil servant, Jakub (Tomasz Schuchardt), who is aware of the horror of the situation, and a lady hydrologist named Jaśmina (Agnieszka Żulewska). They are the only ones who understand that saving the city is at stake. They are both very convincing in this because they are looking at the flood from the outside, as it were. Jaśmina studied hydrology in the Netherlands and has previously researched major floods similar to the upcoming one. So she takes a much broader view of the threat than the inhabitants of Lower Silesia. Jakub, on the other hand, is a local government official, the right hand of the governor, but also a former anarchist who has kept his distance from the world of politics, including local politics. Besides, Jaśmina comes from the Netherlands to a country where male decision-makers are very reluctant to listen to the advice and recommendations of women - even experts - because here it is traditionally the man who assesses the situation and makes decisions.

The misfortune that was the 'flood of the century' has, paradoxically, turned out to be very lucky for the Polish series filmed for Netflix. For not only 'Wielka woda' but also an earlier series from 2018 called 'Rojst' was a success in every respect, especially since both films have the same director, Jan Holoubek. Here we watch the story, spread over two seasons, of an investigation into the murder of a teenager whose remains were uncovered by a high flood tide. We also see two different countries, one from the 1980s and one a decade later. Poland of the era of intimidation and Poland of the wild early capitalist momentum. Poland of repression and confusion and Poland of the fulfilment of newly awakened ambitions, Poland of the appetite for power and money; often an unrestrained appetite that goes as far as crime. A superb group of actors, from Andrzej Seweryn to Magdalena Różdżka to Łukasz Simlat, showed off here.

Netflix has also launched one of the most prominent fantasy characters native to Poland, namely the Witcher from the series of that title. He is a character from the fantasy saga by Andrzej Sapkowski, who long ago ceased to be exclusively Polish. The Witcher (the equivalent of a female witch) Geralt of Rivia, created by him, hires himself out as a professional assassin of monsters that threaten the inhabitants of a medieval-style land. Thanks to Netflix, 'The Witcher' has grown into an extensive saga; its universe will probably continue to expand for a long time to come.

In a different direction went a series entitled '1983' from 2018. It is quite a successful political fiction, in which a radical terrorist attack from the year mentioned in the title dashes Polish hopes of independence from the Soviet Union. Ten years have passed, and instead of the expected Third Republic, we still have a country panting under Soviet oppression. Fortunately, there is a group of righteous people who will undertake to reverse the course of history.

A still from the series "Wielka woda", Episode 6 (Source: Netflix)

And the conclusion. In the 'Wielka woda' series, we watch a classic film denouement at the end, i.e. a great relief after the cataclysm. The waters recede and the inhabitants set about cleaning up the damage and rebuilding Wrocław. And, above all, they learn lessons. They already know that in our world — whether of climate change or epidemics — hazards cannot be treated as episodes. They must be studied and, on their example, we must prepare for the next ones. It is not known what these threats will be and when they will come but they will certainly come.

This article was originally published at dlapolonii.pl internet portal.