Gdańsk as a Free City

On March 19, 1919, the Supreme Council of the Versailles Conference decided that Gdańsk would be a Free City under the protection of the League of Nations. The Free City of Gdańsk was established on November 15, 1920. It had its own constitution, anthem, parliament and senate. The official language was German.

In the period from 1920 to 1939, the Polish population comprised between 9 and 13 percent of the city's population. The majority of the German population was very unfavorable towards Poles.

In August 1939, the hostile attitude of the Germans towards the Poles and Jews living there reached a climax.

There were mass searches and arrests among the Polish population, and the persecution of the Jewish population intensified.

Polish customs posts have become the target of constant attacks and even arson. Polish postmen and civilians were attacked and beaten.

In such an atmosphere of increasing tension and constant provocations from the German side, the case of the Free City of Gdańsk became one of the main pretexts for the invasion of Poland by the German Third Reich and the start of World War II. It was the next stage planned by Hitler in the conquest of all Europe.

The Polish Military Transit Depot on the Westerplatte Peninsula was an uncomfortable symbol of the Polish presence at the entrance to the port of Gdańsk.

On December 7, 1925, League of Nations granted independent Poland the right to maintain military guard and store ammunition there.

Major Henryk Sucharski was the commander of the Military Transit Depot and second in charge was captain Franciszek Dąbrowski. The crew as of September 1’st was over 200 soldiers (historical sources indicate between 205 and 210 military trained men).

Hitler's Trojan Horse.

On August 25, 1939, the school battleship "Schleswig-Holstein" came to Gdańsk on a courtesy visit. In fact, it was a well-armed ship, prepared for a previously-planned attack on Westerplatte.

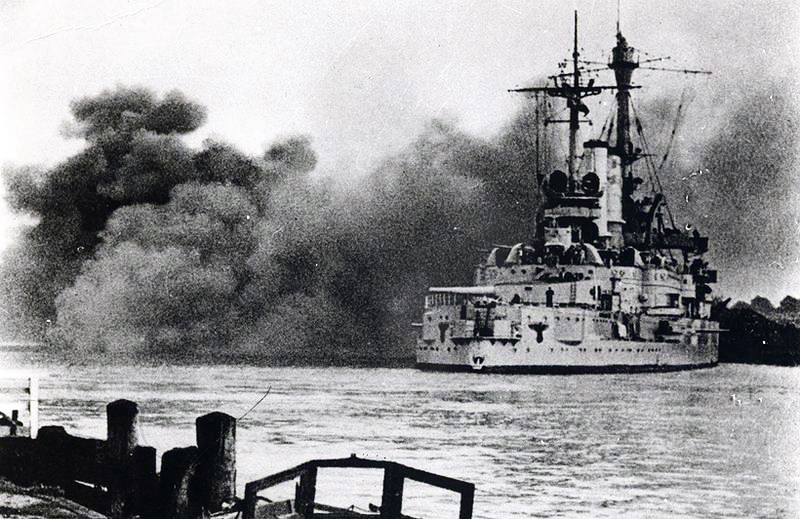

Battleship Schlezwig-Holstein shells Westerplatte in 1939. (public domain) The official purpose of the visit of the battleship, launched in 1908, was to commemorate the sailors of the German cruiser "Magdeburg" sunk by its own crew during the battles of the First World War in the Gulf of Finland. Sixteen sailors who died then were buried in the Garrison Cemetery in Gdańsk.

There were even diplomatic visits and returns aboard the battleship, combined with dinners and champagne toasts. The commander of the battleship Schleswig-Holstein, Commander Gustav Kleikamp, paid a visit to the High Commissioner of the League of Nations, the President of the Senate and even the Commissioner General of the Republic of Poland.

Marian Chodacki, who held this position at the time, remembers the diplomatic visit on board the battleship (whose intentions, despite appearances, were clearly hostile) as one of the most difficult days in his life.

The real, although secret, task of the battleship was to fire at Gdynia and Hel. The task was changed when the commander of the battleship, Gustav Kleikamp, in consultation with the main command, decided that Westerplatte should be taken first.

The Germans thought this task would be easy and quick to perform.

The German intelligence provided information (which turned out to be untrue) that Poles had no more than one hundred infantry soldiers in their barracks. The Germans planned to deal with the "Westerplatte problem" in two or three hours at the most.

Defenders of Westerplatte

As it results from the then secret order of the Department of Infantry of the Ministry of Military Affairs of February 28, 1939 under the reference number I.303.3.103 (L.dz.668 / Tjn.Org. R-112) regarding the staffing, the crew of the Military Transit Depot at Westerplatte consisted of soldiers specially selected for psychophysical conditions.

The professional cadre of the platoon (14 people) was to be appointed from the infantry regiments, and all non-commissioned professional officers - from the line group. Non-commissioned officers and riflemen of basic military service were appointed from soldiers conscripted in the spring of 1938 (born in 1916) to 4 pp. Legions in Kielce. The soldiers of the sentry platoon still belonged to their home regiments in terms of record keeping, and in terms of service, full-time and economic activity - to the Military Transit Depot at Westerplatte. Particular importance was attached to the selection of soldiers for the guard platoon, which determined the combat value. Psychophysical criteria were strictly defined. Designated soldiers: officer, non-commissioned officers and privates had to meet the following conditions:

officer - non married, very good professional and moral qualifications,

non-commissioned officers - bachelors (a certain percentage may be married, provided that the families are not brought to Gdańsk), very good service and moral qualifications, of Polish nationality, not subject to court and disciplinary punishment for offenses against military discipline and service loyalty, no addictions and not indebted,

privates - without court punishments, politically confident, of Polish nationality, height desirable from 170 cm up ”. Due to the nature of the service in the guard platoon in Westerplatte, the assignment to this platoon of officers, non-commissioned officers and privates should be treated as a distinction - according to the order. The soldiers were also informed that they would not be given leaves at Westerplatte. However, they could use the local beach and sea baths.

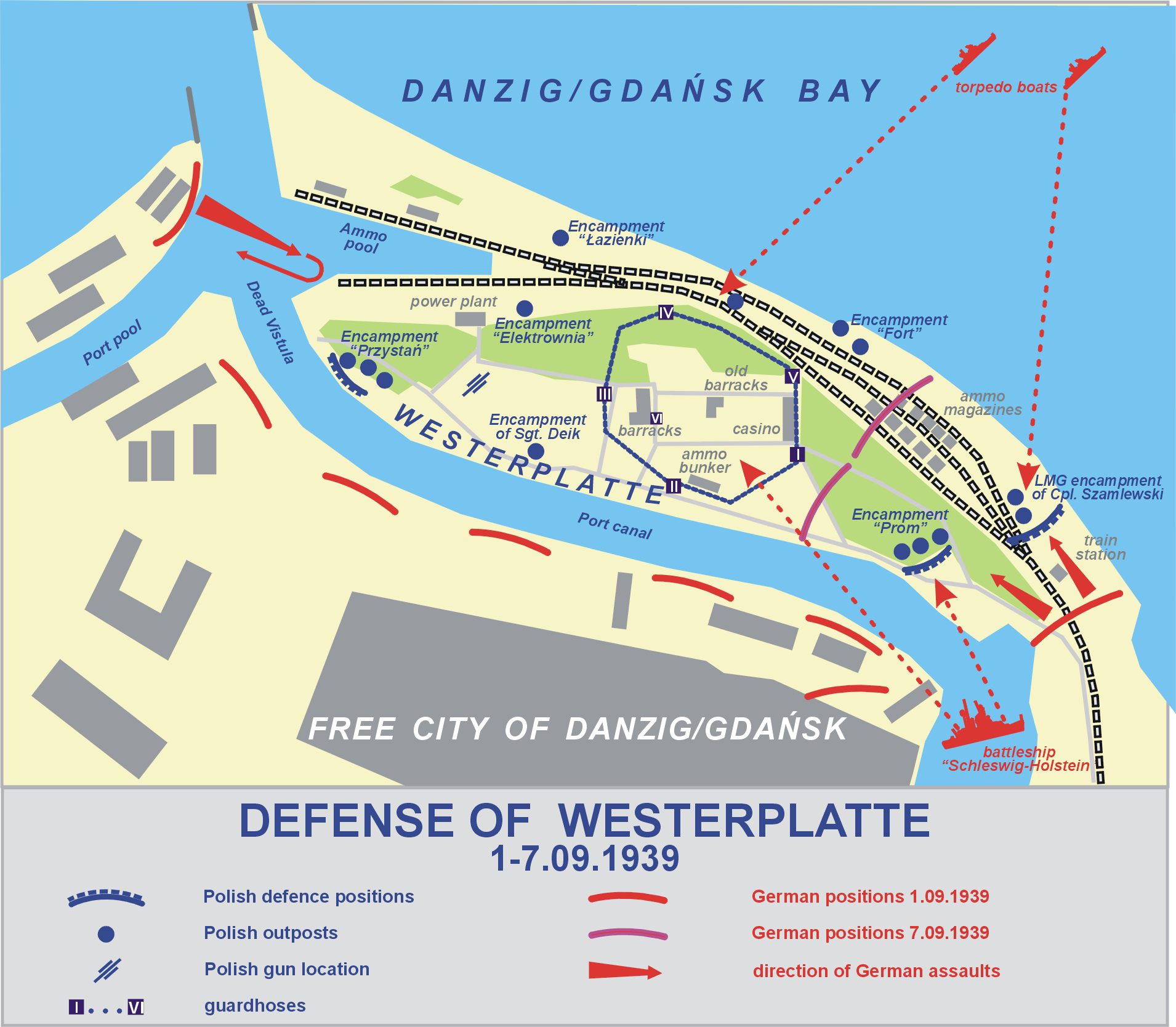

Westerplatte’s defense system. The entire defense system of the peninsula was built in secret from 1933. The German intelligence failed to obtain true information about the location of fortifications and the details of the armament of the Military Transit Depot.

The Defense of Westerplatte

Weapons were secretly brought to Westerplatte, the best that the Polish army had at that time.

The depot crew was replaced, initially periodically and then every six months. The last exchange, which took place in the spring of 1939, was used for the clever, though illegal, increase in the manpower.

Civilian workers employed in the transit depot, dressed in military uniforms, were taken by a Navy tugboat to Gdynia, where they changed into civilian clothes in the barracks of the 2nd Marine Battalion in Redłowo and returned to their homes.

The military uniforms they left behind were put on by Polish soldiers, who then returned by tugboat to Westerplatte, thus increasing the group of trained soldiers without the knowledge of the Germans. The next day, civilian workers arrived to work overland.

Thus, at least 81 people joined the Westerplatte crew.

On the eve of the outbreak of the war (which was to be expected due to the increasing tension), the supply of weapons, ammunition, medicines and first aid became a problem. The transport of weapons and medical supplies prepared by the Polish Commissariat in Gdańsk, which went by rail, was taken over by the Germans.

There was a shortage of ammunition, automatic and heavy duty rifles, drugs and surgical instruments in the Westerplatte finger.

Literally on the last day before the attack, thanks to the courage of two soldiers who went to the mainland dressed in civilian clothes, it was possible to bring to the depot a significant part of the missing equipment, which was prepared by the head of the Military Department at the Polish Commissariat in Gdańsk, Col. infantry, Wincenty Sobociński.

The German attack that started the Second World War.

On September 1, 1939 at 4.45 am (according to the ship's log book at 4.48 am) the attack of the German battleship "Schleswig-Holstein" on Westerplatte took place. To this day, this aggression is considered the beginning of the Second World War.

The Polish staff of the Military Transit Depot, consisting of just over 200 soldiers, heroically defended the facility against enemy attacks from sea, land and air until September 7, 1939.

The main commander of the depot at Westerplatte, responsible for the strategy of the entire defense, was Major Henryk Sucharski, and his deputy and at the same time line commander, Capt. Franciszek Dąbrowski, whose task was to conduct combat operations directly.

The defenders of Westerplatte did not allow themselves to be surprised, but from the very first moments they had to constantly repel massive assaults by the vastly outnumbered Germans. Simultaneously with the launch of the first missiles from the sea from the battleship deck, the Westerplatte facility was attacked by the Kriegsmarine naval assault company and the SS company "Danziger-Heimwehr" mobilized in Gdańsk.

In total, the Germans directed about 3,400 of their soldiers (although these data are not fully accurate) and conducted hurricane artillery fire.

On the second day of the fight, German forces carried out a murderous raid of Ju-87 dive bombers on Westerplatte.

It was then that the orderly of Major Sucharski, Józef Kit, who enjoyed great sympathy of his superior, died, and the major himself suffered a nervous breakdown, as a result of which he was temporarily removed from command by the officers of the facility. The major's beloved pet, the purebred dog Eros, survived the attack and was taken in by one of the German officers after the end of hostilities.

The rescue will not come.

Major Henryk Sucharski was the only one who knew about it. Commander of Westerplatte was informed about the impossibility of rescue from the outside by his superior from the Polish Commissariat in Gdańsk, Lt. Col. Sobociński, in a confidential conversation on August 31, one day before the German attack. It was then that Major Sucharski was tasked with maintaining the defense of the Westerplatte facility for 12 hours.

Perhaps this awareness of the hopelessness of the situation in which the soldiers he commanded and himself found themselves contributed to the major's health indisposition on the second day of defense. According to some witnesses, the nervous breakdown of September 2 was accompanied by an epilepsy attack.

From that moment on, the defense was actually commanded by Capt. Franciszek Dąbrowski. However, he remained loyal to his superior and gave orders as if they had been agreed with the major.

Capt. Dąbrowski was a staunch opponent of premature surrender and, despite increasingly heavy attacks from the German side, did not want to give up. The situation in Westerplatte was getting worse by the day. The defenders, under constant fire from the enemy, exhausted by the fight, lack of sleep, constant threats to life and lack of food, showed remarkable steadfastness and courage. They fought to the last minute with great dedication.

“Westerplatte is still defending itself! The Supreme Commander greets the heroic crew ”- these were the messages coming from the radio speakers from the second day of the struggle until the capitulation. They cheered and cheered all Poles to fight at the beginning of the September campaign.

It was then that the legend of a handful of defenders who relentlessly faced the enemy in extremely difficult conditions, with no hope of rescue, was born.

The Supreme Commander of the Marshal of Poland, Edward Śmigły-Rydz, gave the order on September 4, 1939 to award each of the soldiers defending the facility with the order of Virtuti Militari and to be promoted by one military rank.

Capitulation

Meanwhile, the number of people injured in Westerplatte was increasing day by day, and their condition was deteriorating due to the lack of drugs. The medical chamber was bombed on the second day of the struggle. 14 soldiers were killed and one died from injuries.

Two days after his health indisposition, Major Sucharski recovered, but saw no further sense of the fight and urged the officers' staff to surrender. Perhaps realizing that he could not expect outside support under any circumstances, he wanted to save the lives of his soldiers and felt that they did their best by defending the outpost fiercely for much longer than the recommended 12 hours. The fact that they endured in battle for almost 7 terrible days under constant fire from the sea, land and air became a symbol of their steadfastness, a fully completed military task and dedication to their homeland.

On the seventh day of this unequal fight, Major Henryk Sucharski made the difficult decision to surrender. At the last briefing, he said: "If the defense is broken, we surrender."

It was then that the symbolic white flag was displayed. According to an eminent expert on the subject, Dr. Andrzej Drzycimski, there is no evidence that this happened earlier, on the second day of the fight, as some historians have suggested.

Did Major Sucharski do the right thing? It is not for me to judge, but according to many, the decision was fully justified. In this way, the commander saved his heroic soldiers from complete extermination, who had endured seven long days in this terrible fight.

The Germans appreciated the heroism of the captive defenders of Westerplatte, treating them with military honors, and allowed Major Sucharski to keep his saber symbolically at his side.

Friedrich-Georg Eberhardt and Henryk Sucharski, Westerplatte, 1939 (Source: Wikipedia) The defense of Westerplatte is a special page in the history of the Polish nation. It is a symbol of steadfastness, extraordinary courage and bravery of Polish soldiers.

The memory of the soldiers from Westerplatte.

After the end of World War II, the fate of these heroes varied.

After the defense of Westerplatte ceased, they were held captive as prisoners of war in German soldiers camps (stalags and oflags), but also in concentration camps and Soviet labor camps.

Some managed to escape. Then they continued to fight on the Western Front in the 1st Polish Corps of the Polish Armed Forces or in the ranks of the Home Army.

Those who followed the Polish People's Army took part in the capture of Berlin. Unfortunately, not all of them received deserved glory. In communist-ruled Poland, dependent from the Soviet Union, there were cases where they were deported to distant Siberia as "politically uncertain” or the enemy of the state or imprisoned in communist prisons. Many of them were forgotten and degraded.

Major Henryk Sucharski

He was sent to the POW camp in Stablack and later to Oflag II D Gross-Born. After being liberated by British troops in 1945, he joined the 2nd Polish Corps in Italy. After the end of the war, he became the commander of the 6th Carpathian Rifle Battalion.

A year after the war, Major Sucharski was taken to the British military hospital in Naples, where he died on August 30, 1946 of peritonitis. He was buried at the Polish Military Cemetery in Casamassima, Italy.

In 1971, his remains were exhumed, and the urn with the ashes was transported to Poland and solemnly buried on September 1 in Westerplatte.

Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski

It was he who led his soldiers, leading them to captivity after the announcement of the surrender of Westerplatte. He was in POW camps and then returned to Poland. In 1950, Dąbrowski, recognized as a war vetran, was released from military service. It was a blow to him, as he was not due to military retirement yet. Together with his family, he left Baltic Coast and moved to Kraków, where he took a job as a cashier in a bookstore and for some time sewed slippers for a Kraków cooperative. The stay in prisoner of war camps put a lot of strain on his health.He was sick with tuberculosis. Staying in hospitals saved him from arrest in Stalinist times.

The heroic defender of Westerplatte was recognized in Poland as a "hostile Sanation officer". Only after the temporary easing of the communist regime in October 1956, Lieutenant Commander Franciszek Dąbrowski was rehabilitated. He received compensation and was restored to favor. At the same time, he worked to create a union of soldiers with Westerplatte. He died on April 24, 1962 in Krakow. He was buried at the Rakowicki Cemetery.

All of them, as brave soldiers, deserve to be commemorated, and therefore it seems reasonable to decide that on September 1, 2020, for the first time, the celebration of the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II in Westerplatte will be organized by the Polish Army. The heroic defenders of Westerplatte are to be respected by the entire Polish nation, but the memory of them should first of all be taken care of by soldiers who model themselves in their service on their steadfast attitude.

Honor the defenders of Westerplatte.