Poland regained independence in 1918 after 123 years of absence on European political maps and division under Russian, Austro- Hungarian, and German rule for over a century. It was supported by the official U.S. pro-Polish policy dating back to 1915, eventually spelled out in President Wilson's Fourteen Points. Despite the human and material losses from 1914-1918, which are difficult to estimate accurately, the process of shaping the borders and political systems of the reborn Second Polish Republic began on November 1918.

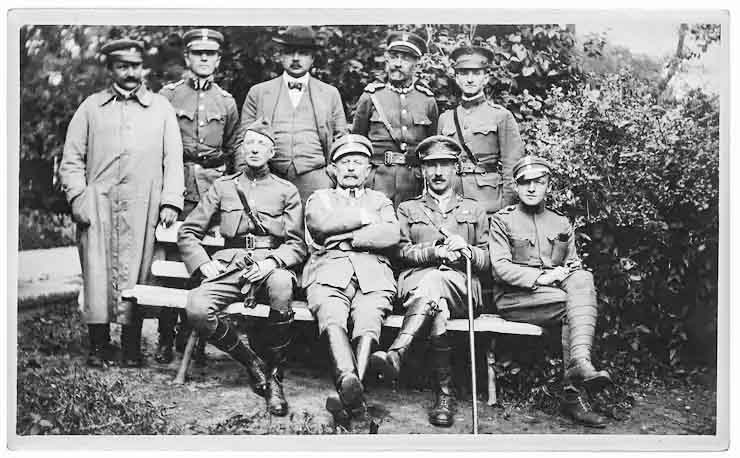

Joe T. Marshall (standing, farthest right) with members of the 1919 Red Cross Inter-Allied Medical Commission, sent to investigate the typhus situation in Poland, and officers of the Polish Army, Poland, 1919. (Źródło: Photo by Joe T. Marshall, courtesy of Harvard University Archives)

The rebuilding process was arduous, both externally and internally, integrating three partitioned territories into one. The ambiguity of the Treaty Versailles on Polish borders led to military conflicts with neighboring countries, compounding the effects of infectious disease epidemics of typhus, Spanish flu (1918-1919) and hunger. There were also other epidemics of smallpox, cholera, STD, and other diseases.

President Woodrow Wilson established the United States Food Administration (USFA) on August 10, 1917. The U.S. had to provide food to its armies and the Allied armies, Allied civilians, and Americans at home. Herbert Hoover was the head of the USFA when that organization was wound down with the November 1918 Armistice. The American Relief Agency succeeded it. In 1919, American Relief Agency (ARA) was formed with an over 100 million USD budget.

Humanitarian workers from the United States traveled after World War I to countries in Europe devastated by military action, whose governments could not care for those most in need. The American relief effort far exceeded that provided by Great Britain, Italy, and France combined. ARA continued efforts helped to stabilize the economy, created jobs, and encouraged product exchange between Central European countries. Polish Government secured loans and credits from American Banks on very favorable terms. Polish Americans were encouraged to support the loan by buying Polish Bonds. With the arrival of the American Red Cross doctors, nurses, and dentists, the aid started flowing with food, medical supplies, and clothing. The first ship arrived in Danzig (Gdansk) in January 1919. A group of Polish Gray Samaritans affiliated with ARA arrived in June 1919. The aid stabilized and sustained the fragile Polish Government.

There was growing concern with the spread of Bolshevism gaining westward ground in Central Europe and the spread of the typhus fever epidemic. Typhus was endemic in Russia well before WWI, but the typhus outbreak started on the Eastern Front in Serbia in 1914. The spread of typhus likely started with the Russian army entering Polish lands in 1915, crisscrossing refugees and armies.

Infected lice transmit typhus, which is especially problematic in vulnerable populations affected by wars, revolutions, imprisonment, crowded encampments, and ships, compounded by famine and sanitary system infrastructure destruction. Typhus was first described in Italy in 1546 by Fracastoro.

It is estimated that by the end of 1919, there were over 200,000 cases and over 18,000 deaths related to typhus in Poland. With the war's end, the retreating Austrian and German armies stripped food and medical facilities of equipment and supplies, making the situation much worse. The assessment of the Red Cross-appointed commission recognized the situation as urgent due to the potential risk of the disease spreading across Europe, but it lacked funding.

Employees of American aid organizations arriving in Europe after World War I sought active cooperation with local associations and representatives of local authorities. Eventually, the U.S. Typhus Relief Expedition delegates, led by Army surgeon Colonel Harry L. Gilchrist, assisted with organizing the response to the typhus epidemic in Poland. Gilchrist worked closely with the Polish Ministry of Public Health and its Central Committee headed by Prof. Emil Godlewski, Dr. Wiktor Hryszkiewicz, and Dr. Ludwik Rajchman. Colonel Gilchrist had experience in similar campaigns in Belgium and France.

The arrival of the U.S. Typhus Relief Expedition to Poland in August 1919 started with an educational campaign about the disease's spread, the role of lice as a vector, and the need for sanitation. "The attack" was executed by the Medical Corps unit entirely funded by the American Army. The American Army sent clothes, hair clippers, soap, portable beds, baths, mobile laundries, vehicles, and steam disinfecting plants to the Polish nation. A historian, Christopher Blackburn, states, "In the years from the end of the First World War after the Polish-Bolshevik War, the U.S. delivered over 750,000 metric tons of supplies to Poland, valued at $200,000,000. "

All residents were ordered to clean themselves thoroughly and clean their homes, farm buildings, settlements, villages, and towns. The refugees from the Ukrainian and Russian territories posed a particular challenge as they were arriving in such numbers that they overwhelmed the system. A quarantine and mandatory delousing were part of the sanitary cordon established along Poland's eastern border. Despite the concerted efforts in 1920, the number of new cases was about 30,000 per month. Many physicians died infected by patients.

Harvard-educated photographer Joe Marshall was tasked with documenting the efforts on behalf of the League of Red Cross Societies. His photographs, along with his journal entries, give witness to the post-WWI devastation from August to September 1919.

The U.S. foreign minister, with whom the commissioners had conferred in Warsaw before venturing into the countryside, had warned that «Belgium is a paradise compared to Poland.» They would find «human sparrows living on grass, bark, and nettle soup.» --Joe Marshall

While the struggles about Polish borders subsided by the summer of 1919, the clashes with the Soviet Bolsheviks did not. The consecutive advancement of the Russian Bolshevik troops into Ukraine and Belarus eventually led to the Polish-Bolshevik War. The military operation of the Polish military was successful, although, in August 1920, the prospect of the utter destruction of Poland was real.

The advance of the Bolshevik army provided a new source of contamination. Winston Churchill believed that spreading the disease helped the Red Army achieve its military objectives. It was estimated that the Soviet invasion wiped out much of the typhus eradication effort, especially in the areas and homes occupied by the Soviet soldiers. The war ended with an armistice in October 1920 and the Treaty of Riga in March 1921.

While the military efforts in the Polish-Bolshevik War were victorious, the fight against typhus was not. The Red Army destroyed much typhus effort, captured the equipment, and damaged medical facilities. While the American Army's mission to entirely eradicate typhus from Poland was unsuccessful, it saved many lives and eased the burden of the epidemic.

Article originally published by the Minnesota Polish Medical Society. Republished with permission.