In a few days, we are celebrating the 40th anniversary of the introduction of the so-called Martial Law — the unconstitutional and (even according to the Polish law at the time) illegal military coup, which was supposed to put an end to the operation of "Solidarity" — a political and social freedom movement under the aegis of an independent trade union. The purpose of the imposition of martial law was to restore the existing social system and thus consolidate the pro-Soviet, communist power in Poland for an indefinite period.

A December Snowy Night

On the night of December 12-13, 1981, the weather was cold and it was snowing practically all over the country. Against the immaculately white scenery, among slowly falling large snowflakes, not only the policemen from the regular MO (Milicja Obywatelska, People's Police), but also ZOMO units (Zmilitaryzowane Oddziały Milicji Obywatelskiej, Militarized People's Police), special groups of the Ministry of the Interior, anti-terrorist units, security service officers (Służba Bezpieczeństwa, SB), and above all, units of the Polish army, including tanks and armored vehicles, and even paratroopers/commandos, in full combat gear and with live ammunition, descended on Polish cities.

According to the available data, approx. 70 thousand soldiers took part in the operation, over 30 thousand officers of the Ministry of the Interior, over 40,000 reservists, 1,750 tanks, approx. 1,900 armored vehicles, over 9,000 cars, several squadrons of transport planes and helicopters, and several dozen warships blocking access to ports.

As part of the operation code-named "Azalia" (eng. Azalea), the security forces of the Ministry of the Interior and the Polish Army seized the facilities of the Polish Radio and Television and blocked domestic and foreign connections in telecommunications centers. In turn, groups of policemen and SB functionaries joined, as part of the operation code-named "Fir" (pol. Jodła), to intern "Solidarity" activists and leaders of the political opposition. ZOMO branches seized the premises of the regional offices of "Solidarity", arresting the people there, and securing communication and printing devices. Armored and mechanized units were sent to the cities and located near the most important strategic objects, such as communication junctions, exit routes, main intersections, official buildings, etc.

A column of tanks on the way to Poznań, December 13, 1981 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

I remember watching with trepidation and some fear, from the window of my family's apartment on Marymoncka Street, between the Meteorological Institute (PIHM) and the Academy of Physical Education (AWF), watching a long column of tanks from the north, from Gdańsk or Modlin, to Warsaw. The tanks were moving towards the City Center, and despite the falling snow, which muffled them noticeably, the rumble was so strong, that the windows rattled loudly. It was just after midnight, and the sound woke me up from my first sleep. Observing the tanks, I was consoled a bit with the realization that I did not see any red stars on the turrets of the tanks, so they were "ours" — part of the Poland-against-Jaruzelski war, as it was later humorously described by the author of the book with this title (Wojna polsko-jaruzelska), prof. Andrzej Paczkowski. Little consolation, but something nevertheless. Only in the morning, it became clear what the tanks were really there for.

In Gdańsk, in the cradle of "Solidarity", where the National Commission met on Saturday and where, therefore, many union activists and advisers were present, about 30 members of the Commission and several advisers were detained during the night. That night, many union activists and independent intellectuals were "interned", including the organizers and participants of the Congress of Polish Culture in Warsaw. The word "interned" is such a euphemistic Newspeak typical of the communists: more accurate to say that they were unceremoniously deprived of their liberty, that is, they were simply arrested.

In total, about 5,000 people were interned in the first days of martial law, people who were held in 49 isolation centers across the country. In total, during the martial law, the number of internees reached 10,000. A large proportion of Solidarity's national and regional leaders, advisers, members of factory committees, democratic opposition activists and Solidarity-related intellectuals were imprisoned.

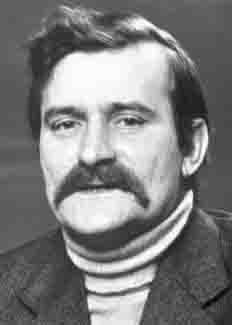

Lech Wałęsa (1943-), the Chairman of the "Solidarity" Union and, later (1983), Nobel Peace Prize laureate (Source: nobelprize.org)

The chairman of the union, the charismatic Lech Wałęsa, a real "man of the people", who was already a world celebrity at that time, was treated in a special way, because the authorities hoped that they would be able to persuade him to cooperate and use him politically. He was interned and isolated from other Solidarity activists in a villa near Warsaw. However, he rejected the offers of cooperation[*] and finally — after detaining him in Chylice and Otwock — the authorities placed him in the government center in Arłamów.

The severity of regulations and orders, and the official declaration of the military usurping power, made Poland, in effect, a "country under siege."

Sunday morning, but no «Teleranek»

«Teleranek» was a public television (the only television at the time) program for small children, normally broadcast every Sunday morning at 9 a.m.

In the morning, all the telephones were dead — deaf, and with no dial tone. No one could be contacted. It was not even possible to call the fire brigade, or an ambulance.

General Jaruzelski announces the martial Law on December 13, 1981 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

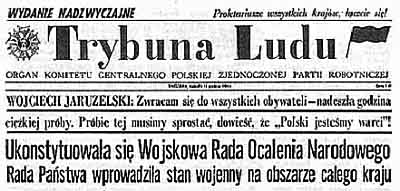

The TV set, switched to the only functioning channel, TVP 1, broadcast gloomy classical music. At 10:00 am, on the hour, the tones of the Dąbrowski Mazurka — the national anthem — began to be heard, and the obligatorily uniformed and well-known figure of General Wojciech Jaruzelski — holding all of the most important government posts in the country — appeared at that time. The figure supposedly familiar, but this time it looked different because, instead of the typical dark glasses, the general looked menacingly and gloomily through the thick reading spectacles. So he began to read the message to the nation, prepared and refined the previous evening:

Citizens of the Polish People's Republic!

Today I am addressing you as a soldier and head of the Polish government. I am addressing you in matters of the highest importance.

Our homeland is on the edge of the abyss. (...)

I announce that today the Military Council of National Salvation has been formed. The Council of the State, in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution, today introduced martial law throughout the country at midnight.

In the name of the national interest, a group of people who threatened the security of the state were interned as a precautionary measure. This group includes extreme activists of "Solidarity" and illegal anti-state organizations.

(...)

This message was also broadcast every hour on the first and only program of the Polish Radio on that day, over the long waves, giving it nationwide coverage, from 6 am onwards.

Nobody could have any doubts: a state of emergency was introduced — called martial law, because formally, the "emergency" could not be legally declared throughout the whole country.

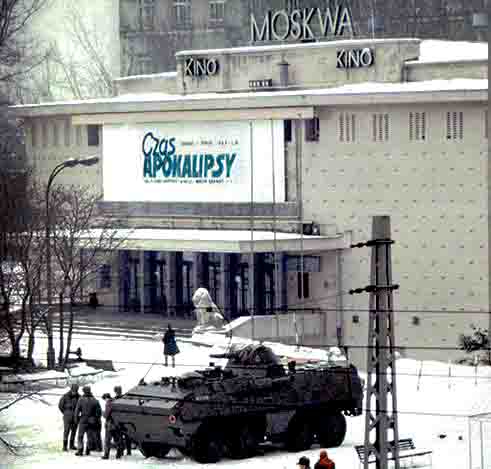

13 December 1981, in front of the movie theater "Moscow" in Warsaw, with the "Apocalypse Now" poster displayed and an armored vehicle in the foreground — an iconic image full of symbolism, by Chris Niedenthal (Source: Pinterest)

Although sooner or later, just about everyone in the country and abroad expected some repressive moves of the authorities in response to the situation and to the actions of Solidarity, the majority, however, along with the National Solidarity Commission who were meeting in the Tri-City, was caught by surprise that very night.

The Preparations

Today we know that preparations for the introduction of martial law lasted over a year. They were conducted with special care and under the veil of absolute secrecy. Very few in Poland were privy to these plans. They ended on September 13, 1981, and a meeting of the National Defense Committee on that day confirmed that all legal and technical issues, except for minor details, had been addressed.

The main problem was timing. The necessary condition was not only a pretext that the public would find convincing, but also a set of circumstances in which at least a significant part of society would accept a radical campaign against Solidarity.

General Jaruzelski was the commander-in-chief and — as it seems today — the author of the idea of pacifying citizens with the help of his own troops. The 4th Plenum of the UPWP (United Polish Workers' Party, pol. Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) on October 16-18 dismissed Stanisław Kania, the successor of Edward Gierek, from the position of First Secretary and replaced him with Jaruzelski. The transfer of power took place not only with the consent of the Soviets, but probably on their initiative.

Jaruzelski then assumed all key positions in the country — that of prime minister, the chairman of the National Defense Committee, and the Minister of National Defense — as well as the leading party position. However, he was in constant contact, under the supervision and control of the Soviet authorities. In his preparations, he was under the control of, among others, the commander-in-chief of the Warsaw Pact troops, Marshal Viktor Kulikov, who visited Poland several times between August 1980 and December 1981, and other people from his staff, as well as Vladimir Kryuchkov, deputy commander of the KGB.

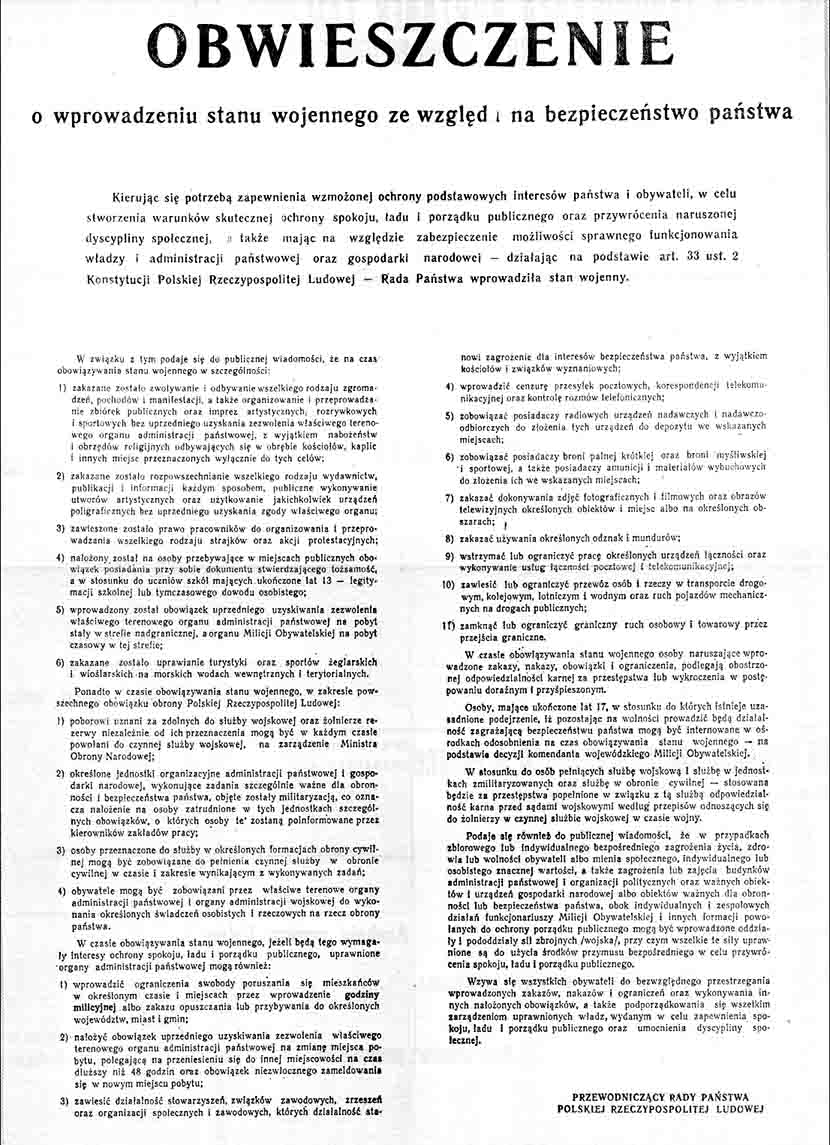

Many months earlier, drafts of various legal acts for the purposes of martial law had been drawn up, 100,000 copies of the announcement of its introduction were printed in the USSR, lists of military commissioners to take control of the state administration and larger workplaces were established, and institutions and enterprises of strategic importance were selected to be militarized, such as railways, power plants, radio and television broadcasting stations, etc.

The (undated!) announcement about the imposition of martial law — among the Poles, such posters conjure the memories of the Nazi occupation (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Since mid-October, more than a thousand Military Field Operational Groups were operating in the area of future action, as they were sent to investigate the situation, although with no knowledge of the true purpose of this operation. Paradoxically, they met with favorable reception from among the general public, because the military uniform in Poland enjoys great respect even to this day.

At the same time, ZOMO units were undergoing intensive training in fighting with and controlling the crowds. I remember the silence that fell on the streetcar that I was traveling in near today's Bank Square (then Dzerzhinsky Square) in early December at the sight of a tight ZOMO column marching around the city in steady steps, shoulder-to-shoulder, clubs in hand ready to strike, with faces protected by plexiglass windows, without any human expression on their faces. At one point, someone on the streetcar commented aloud: "Stoned — capable of anything."

In prisons, places have been prepared for about 5,000 activists of "Solidarity" and the opposition, who were to be arrested on the basis of lists of names drawn up since the beginning of 1981.

The events that led directly to martial law began on December 2, when a strike by students of the Firefighter Academy in Warsaw, taking place since November 24 and supported by Solidarity, was suppressed by special internal security units of ZOMO, which, using helicopters and armored equipment, broke into the school building . I witnessed it personally. The school was supervised by the Ministry of the Interior and the strike was perceived by the authorities as an attack on one of the ministries responsible for national security.

Although "Solidarity" should have treated this event as a "dress rehearsal" before the attack on the Union itself, it was caught by surprise a few days later — it turned out completely unprepared. It must be admitted, however, that as a large, open democratic organization, with over-confident leadership that felt invincible and believed in the inevitability of change in the face of the direct support of 10 million citizens, the Union had no real possibility of preparing for this type of attack.

The Illusion of Legality

At 1 a.m., the members of the Council of State, theoretically the most important office of the People's Republic of Poland, were gathered in the Belweder Palace. Most of them, however, did not know what the purpose of this night meeting was. After an hour and a half of deliberations, the members of the Council adopted the decree about the introduction of martial law, and the accompanying documents. Only the chairman of the PAX organization, Ryszard Reiff, voted against it. All documents adopted were dated December 12, 1981.

The decree about the introduction of martial law was not only pre-dated, but also inconsistent with the law in force at the time. Although the message to the nation referred to the provisions of the Constitution, the Constitution did not give the State Council the right to pass any laws at that time, because the Council could only issue decrees between sessions of the Sejm [the Polish Parliament - ed.]. Meanwhile, such a session was ongoing, and the next meeting of the Chamber was scheduled for December 15 and 16. As anyone knows, authoritarian regimes tend to tailor the law according to their needs and actions, rather than vice-versa, often after the fact, to cover up their tracks. This time, an attempt was made to maintain some semblance of legality, but it was mostly for the benefit of Western public opinion. Anyone familiar with the Polish law has clearly seen how all this was a bit thin.

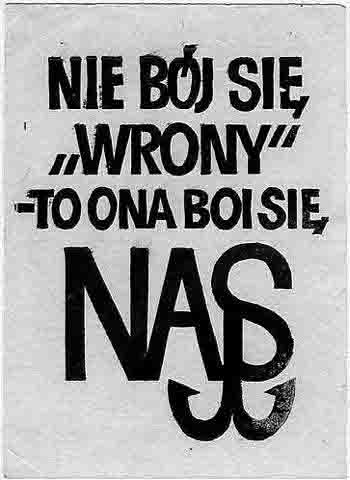

Provisions of the WRON

Officially, the administrator of the martial law was the 21-person Military Council of National Salvation (pol. Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego) — with the rather unfortunate abbreviation WRON [wrona means crow in Polish] — headed by General Jaruzelski. It introduced by its resolution, among others, a curfew from 10 p.m. to 6 am. The freedom of movement was restricted, therefore all gas stations were closed, and a special pass was required for trips outside the place of residence.

All correspondence was officially censored. Telephones were turned off, preventing, among other things, calling an ambulance or the fire brigade. Many of the most important institutions and workplaces were militarized and led by designated military commissioners.

All gatherings were forbidden, and border crossings, including airports, were closed from 6 a.m. Bank disbursement limits and ad-hoc decisions by various judicial bodies have been introduced, along with the extension of the reach of military courts.

A defiantly humorous poster by "Solidarity" stating: «Don't be afraid of WRON [the Crow] - it is afraid of us» (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

It was forbidden to publish in the press, apart from the organ of the communist party, "Trybuna Ludu", the army's newspaper, "Żołnierz Wolności", and selected, "loyal" regional magazines. The activities of all social and cultural organizations were suspended, as well as classes in schools and universities.

"Trybuna Ludu" (The Tribune of the People) headline from December 14, 1981 announcing the imposition of martial law (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

On television, the announcers wore uniform, but without any military insignia. One of the jokes that arose then was the question: "What is the lowest military rank?" Answer: "The television announcer."

In practice, however, the WRON was a façade body. The most important decisions were made by an informal group of military and party members, composed of: General Wojciech Jaruzelski, General Florian Siwicki (Deputy Minister of National Defense), General Czesław Kiszczak (Minister of Internal Affairs), General MO Mirosław Milewski (secretary of the Central Committee of the party ), Mieczysław F. Rakowski (deputy prime minister), Kazimierz Barcikowski (secretary of the Central Committee) and Stefan Olszowski (secretary of the Central Committee).

The Martial Law in Full Swing

The schedule of the meeting of the Solidarity National Commission in the evening of December 12 made it much easier for the authorities to arrest most of the leading national and regional activists, including Lech Wałęsa, in a single operation. The few leaders of "Solidarity" who avoided detention the first night, incl. Zbigniew Bujak, Władysław Frasyniuk, Bogdan Borusewicz, Aleksander Hall, Tadeusz Jedynak, Bogdan Lis and Eugeniusz Szumiejko, immediately started creating underground structures.

On the very next day, December 14, occupation strikes in many large industrial plants were organized independently of one another. Among others, steel mills, including the largest steelworks in the country, "Katowice," and the one named after Lenin, went on strike. Most of the mines, shipyards and ports went on strike, as well as the largest factories, such as: WSK in Świdnik, Dolmel and PaFaWag in Wrocław, or "Ursus" near Warsaw. A total of 199 plants were on strike out of around 7,000 enterprises existing in Poland at that time.

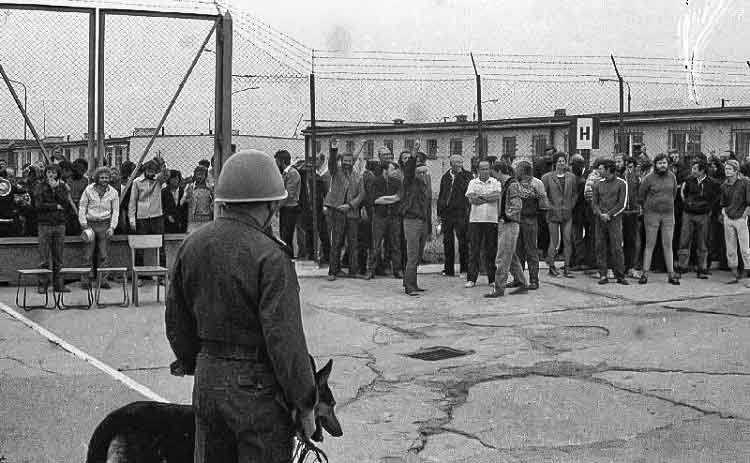

Strikes were brutally pacified in 40 plants, with the use of ZOMO and the army units with heavy equipment. Strikes in mines in Upper Silesia were particularly dramatic, where miners actively resisted. Sometimes, for example, at Katowice steelworks, the police and the army had to "clear the area" many times.

On December 16, 1981, in the "Wujek" Coal Mine, during several hours of fighting, the People's Police used live firearms, killing 9 miners. On December 23, with the support of tanks and helicopter dispatch, the strike at Huta Katowice was suppressed. The longest strikes lasted in the coal mines named "Ziemowit" (until December 24) and "Piast" (until December 28), in which miners were protesting literally underground.

There also erupted street demonstrations, including in Warsaw, Kraków, and Gdańsk, where there were also casualties.

The role of the Catholic Church

One characteristic of the Polish socialism was that, although the Church did not officially engage in political activity, it offered a widely accepted alternative to the communist ideology and worldview. For most Poles, Primate Wyszyński was the highest spiritual authority. Over time, the Church became a player in the growing crisis, and a kind of intermediary between the majority of society and the communist state.

The importance of this institution increased dramatically and permanently in October 1978, when a Pole, Cardinal Karol Wojtyła from Krakow, was elected Pope. In one instant, John Paul II became both a national hero, and a spiritual leader, and the Primate became his messenger.

The papal pilgrimage to Poland in June 1979 is almost universally perceived as a turning point for the country, when millions of Poles welcoming the Pope suddenly realized their strength and understood the relative helplessness of the authorities, who, during the visit, tried to show a good face to the bad game, but practically they had already lost the fight for the hearts of the people.

Pope John Paul II, Primate Card. Stefan Wyszyński, Primate Card. Józef Glemp (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When introducing martial law, the communist authorities decided not to attack the Catholic Church directly. Primate Józef Glemp, successor of Cardinal Wyszyński, appealed from the very beginning for peace and an end to the fighting, at the same time demanding the release of the internees and detainees and a return to dialogue with "Solidarity". On December 13, in his sermon, he appealed to the workers not to risk their lives. Some saw it as a sign of the Church's weakness and submission to the communist authorities.

Lame Reaction from the West

Despite the importance of Poland for the United States and the involvement of American intelligence forces, the crackdown on Solidarity completely surprised both American and Western European elites.

Washington was well aware of the preparations for martial law, mainly thanks to Colonel Ryszard Kukliński, Polish Army officer and a CIA agent with the highest rank in the structures of the Warsaw Pact, a close associate of General Jaruzelski, who not only had full access to information about the coup being prepared, but also participated in the preparations as one of the few insiders, however, the American authorities did not effectively warn "Solidarity" about the planned action.

The CIA — along with many Soviets and even the Poles themselves — did not fully believe that the Polish People's Army was going to be able to carry out this operation on its own. In other words, the United States and its allies were much more afraid of a possible Soviet intervention, and it was precisely for that eventuality that they were preparing, to the extent that they were willing to act at all.

The front page of the British "The Guardian" on December 14, 1981 (Source: "The Guardian" archives)

Officially, the United States acted with a delay and some hesitation against the imposition of martial law, and other Western countries, such as France and the Federal Republic of Germany, were even more delayed and responded with great reserve. The West generally appeared incoherent and unprepared for the way the situation was developing in Poland.

A chasm has opened up among the transatlantic allies. At a time when Washington began to organize a more decisive response, still in essence non-military, the social democratic governments of Germany and France expressed reservations and made it clear that they did not intend to go beyond empty verbal declarations.

On December 23, 1981, US President Ronald Reagan announced economic sanctions against the People's Republic of Poland, and a few days later announced that they would also apply them to the Soviet Union, which, in his opinion, had "serious and direct responsibility for the repression in Poland." Other Western countries also reluctantly joined in the economic sanctions against Poland in the following weeks.

The Reasons for the Creation of "Solidarity"

In order to understand the causes of martial law, one has to go back a few years and, first of all, ask about the reasons for the establishment of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union (pol. Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy, NSZZ) "Solidarity".

The "Solidarity" Union logo (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A critical factor shaping the public mood in Poland in the 1970s was the deepening economic slump and deteriorating material conditions. The rule of Edward Gierek, who took over the position of the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers' Party in December 1970, plunged the country into deep debt to Western countries, but without the accompanying improvement and modernization of the Polish economy. Western money has been largely squandered on shallow propaganda- and politically motivated moves, rather than on systemic reforms.

As a result, the government was faced with the necessity to increase prices, above all for "meat products", first in 1976 — the attempt it immediately canceled in the face of bloodily suppressed, but nevertheless clearly very strong civil protests — but then again on July 1, 1980, which sparked a new wave of opposition that culminated in a wave of strikes that swept industrial plants across the country.

In addition, the relative liberalism of Edward Gierek's policy, a slight opening to the West, in connection with the increasing unlawful and unpopular actions of the authorities, and the amendments to the constitution that outraged the public opinion (for example, the inclusion of a clause about undying love for the USSR), became a source of growing political opposition to the government.

Against this background, on August 31, 1980, the 37-year-old shipbuilding electrician from Gdańsk, Lech Wałęsa, representing the striking Polish workers, sat down to the table with Poland's deputy prime minister, Mieczysław Jagielski, to sign a joint agreement. After many weeks of strikes in many Polish plants, the first free and independent trade union was allowed to be established behind the Iron Curtain. Despite the attempts at delaying it by the authorities, "Solidarity" was officially registered on September 17. It was an unprecedented concession on the part of the communist government. Previous anti-communist protests in Poland in 1956, 1970, and 1976 always ended in failure after bloody clashes with the police.

However, the August Agreements did not succeed in ending either the economic troubles of the country, or the civic protests, which kept growing stronger and more anti-communist. Everyone realized that the signed agreements were a blow to the absolutist power of the communist party and that, sooner or later, the communists would try to regain their influence, at any cost, even with the participation of external forces, i.e. the troops of the Warsaw Pact.

The Reasons for the Dissatisfaction of the Citizens

Supplies and the availability of food and basic items (e.g. toilet paper!) became increasingly limited, and in the early 1980s, a food rationing system was (re)introduced. On April 1, 1981, there were coupons ("cards") for meat and cold cuts, and later for butter and cereal products, sweets and vodka, industrial products — the list of regulated articles continued to grow, along with social dissatisfaction.

The card with coupons (foodstamps) for various groceries (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The fire was further stoked by the widespread belief — at any rate, not completely unfounded — that the lion's share of food and industrial products produced in Poland was sent as part of fraternal socialist "aid" to the Big Brother, that is, to the USSR.

The Soviet Union, already at the end of the 70s, was in a progressive state of collapse. Its leaders (Brezhnev, Gromyko, Andropov) were old people who were unable to undertake radical reforms. The Soviet economy stood on the brink of a collapse, and the Red Army was deeply involved in Afghanistan which, as we know in the USA today, costs lots of money.

This had two significant effects:

- The Soviet Russia needed literally everything, because it lacked everything, and Poland sent in a lot of goods that were desired by the Poles

- The authorities in the Kremlin could not really afford another large-scale political and military involvement, i.e. in Poland.

The latter conclusion was by no means obvious at the time, though. The fear of intervention by Russia and other "allies" was real. Today, it is known that the Polish communist government, on the one hand, assured the Kremlin of its determination to suppress the anti-communist revolution in Poland and began preparations for the imposition of martial law immediately after the signing of the August agreements and, on the other hand, tried to obtain a guarantee from the USSR that — if its own actions should fail — the Soviet bloc will "come to the rescue".

Although it never obtained this assurance — the Soviet Russia was already too weak and deeply entangled in Afghanistan — there was no shortage of pressure from the Kremlin to finally settle the issue of Solidarity and the bottom-up revolution in Poland. This was achieved by the concentration of the forces of the socialist bloc countries around the Polish borders, such as their military exercises "Zapad-81" organized in Poland in early 1981. It is no coincidence that the exercises "Zapad-81" began on the eve of the "Solidarity" congress, and the aircraft carrier "Kiev" anchored off the coast of Poland, from where it was visible from the hotels of some delegates.

Why Did the Soviets Fail to Intervene?

To this day, there is a discussion among historians of that period about the reasons for the lack of military intervention on the part of the Soviet Union and its satellites. We have already mentioned some of the reasons, such as the involvement in Afghanistan and the economic collapse of the USSR.

Apparently, however, the intervention almost came to pass at the end of 1980, after the August agreements. Reportedly, the culminating moment of the crisis was at the meeting of the leaders of the Warsaw Pact in Moscow on December 5, 1980.

The Kremlin was then approaching the end of its patience with Warsaw, and some of the other Pact members were even more impatient. The East German leader, Erich Honecker, in particular, was said to urge Soviets to intervene in fear that Polish events might cause a resonance in East Germany. Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria joined in expressing their concerns. Only Romania warned against intervention at the time — even using that very term, as opposed to euphemisms used by others.

In the end, a decision was made to refrain from intervening, at least for the time being. Although Poland played an important role in the Warsaw Pact and it was crucial to preserve the unity and integrity of the socialist camp — it was precisely for these reasons that Moscow chose to invade in 1956 (Hungary) and 1968 (Czechoslovakia) after all — the Polish population has always been particularly anti-Soviet and difficult to control. The fear of violent resistance and bloodshed was considerable.

It was reportedly on the night of April 3-4, 1981, when the first secretary, Kania, and Jaruzelski held a top-secret meeting in the border town of Brest with Marshal Ustinov and the head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, a member of the Politburo, during which the Soviets agreed that the operation would be carried out by Polish forces, without the participation of allied troops.

However, pressure from Moscow and its satellites persisted. Apparently, Jaruzelski received an "invitation" to the Kremlin for December 14. It is not difficult to imagine the tone of the conversation with Brezhnev if the expected decision had not been made in Warsaw. The introduction of martial law made the meeting unnecessary.

The End of Martial Law

Martial Law was officially suspended only on December 31, 1982, and completely canceled on July 22, 1983, but repressions continued for several years.

Until the autumn of 1982, violent street demonstrations continued, resulting in many people being killed, and in the arrests of thousands of demonstrators and activists from "Solidarity", whose union was officially "banned".

The exact number of people who died as a result of the imposition of martial law is not known. The proposed lists of victims range from several dozen to over a hundred names. The number of people who lost their health during this period as a result of persecution, beatings during the investigations, or during street demonstrations is also unknown.

One thing is certain: as a result of the "Solidarity" revolution, the collapse of the communist system was initiated, and thus contributed to the end of the nearly half-century-long Cold War. The Cold War ended with a bloodless de facto victory for the West, in the form of democracy and liberal economy in the post-communist countries. One could speculate that it would not have ended thus — or perhaps it would not have ended at all — if Polish officials had not first announced the fateful increase in the prices of "meat products" on July 1, 1980, and then had "Solidarity" not been established.

The Anniversary Discussion Panel in Wisconsin

On Monday, December 13, 2021, at 7.00 p.m., on the 40th anniversary of these events, at the Polish Center of Wisconsin in Franklin (941 South 68th Street, Franklin, WI 53132, tel: 414-529-2140), a discussion panel will be held, organized by the Polish American Congress – Wisconsin Division, in which the author of this article, and several other much more distinguished and decorated activists and participants, will present their recollections of the events and answer questions from the audience. We invite all interested to join! Admission is free.

* Note Regarding Lech Wałęsa

Ever since the political transformation in Poland in 1989, there have been accusations that Lech Wałęsa cooperated with the Security Service (Służba Bezpieczeństwa, SB). In 2017, an expert opinion prepared for the purposes of the investigation conducted by the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN) showed, on the basis of a handwriting study, the authenticity of documents in which Lech Wałęsa was to agree to cooperate with the agency (there were also opinions questioning this). Lech Wałęsa himself consistently denies cooperation with the SB. (Source: Wikipedia (pl))

Proceedings concerning the alleged forgery of operational documents of the Security Service from 1970–1976 to the detriment of Lech Wałęsa were initiated on February 25, 2016 in connection with his public statements. In 2018, the Branch Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation in Białystok formally dismissed the proceedings, effectively confirming the authenticity of the documents. On December 8 this year, the IPN announced in a statement that Lech Wałęsa was summoned to the prosecutor's office in order to give explanations in the investigation regarding his false testimony. (Source: IPN (pl))

Corrections and Additions

- December 13, 2021 — Added the bibliography section that was originally omitted.

- December 16, 2021 — Added a footnote about the possible collaboration of Lech Wałęsa with the security apparatus (Służba Bezpieczeństwa, SB)