The village of Polonnoje has been spreading broadly on the steppes on the bank of the Chomora River for several centuries. Currently, it is perceived as a "paradise center" in the Chmielnik region. The population of this town is approximately 22,000. Certainly among them (though not many) are those who remember those tragic events that took place over 80 years ago. Back then, thousands of the region's inhabitants were shipped in freight wagons into the unknown, to the "promised land" by the Soviets. One of the thousands of exiles was my grandfather - Emanuel Oczkowski.

He was born on September 19, 1917 in the village of Tadeuszpol in the Polish region, in the Vinnytsia Oblast (today's Ukraine). He completed 4 years of elementary school, and later life became his university. My great-grandfather was seriously ill and 11-year-old Emanuel was under the obligation to look after his large family. A family of six had to be fed. But that wasn't the worst of it.

In 1936, it was announced to the villagers that in four days all Polish families would be relocated to faraway Kazakhstan. They were told there was a lot of land and work there. They were allowed to take clothes, household utensils, a month's supply of food and one or two animals. They were going to get all the other things at the destination. Later, while studying the history of the resettlement of Poles to Kazakhstan, I came across a shocking historical document: According to the USSR NKVD Instruction about resettlements, it was recommended to tell people that in a new place, Kazakhstan, they would be settled in free lands, where they would receive 25 ha per farm will be exempt from taxes, compulsory delivery of grain and meat to the state for a period of three years. They will be given a convenient loan to settle in their homes.

The people did not really believe the commissioners, but there was no option but to get ready for the long journey. So they packed things, dried biscuits, melted lard, and poured potatoes into sacks. Just after a week, people and their belongings were transported on carts and trucks to the Żużel railway station and under the escort of NKVD troops, and they started to be "loaded" onto the train, into identical freight cars, then the doors were bolted and the train set off. They rode with long stops, during which they unloaded the corpses of the dead from diseases at the stations, fed and milked the cows. They lost track of the days, when the steam engine gave a long whistle and stopped. We have arrived - they whispered in the cars. There was an inscription on the tiny ignition switch building: Taincza Station. Later it grew into the city of Krasnoarmyesk in the former Koksheta, and now in the North Kazakhstan region. The whole square by the station was full of carts and after unloading, a slightly different train headed by a horse-drawn commander set off from the city to the endless steppes. The displaced people expected being brought to some inhabited place, but the command: "Unloading!" was issued in the bare steppe covered with polyps, without any traces of houses or roads. The commander stuck a pin with the sign, Point No. 11, into the ground and said: We will live here. In memory of their distant, flourishing homeland, the displaced people called their new place of residence the Green Grove. At a distance of 50 kilometers, Jasna Polana, Kalinówka, Wiśniówka, and Winogradówka (Vine Grove) appeared, although no grapes were grown in the raw Kazakh steppes.

The people who landed on the bare steppe had to learn to live in the new conditions. Their first occupation was digging a well, then they were extracting clay, which they mixed with grass, formed bricks, dried them in the sun and built clay huts that allowed them to hide from the wind and survive the coming winter. Whoever had not managed to build a hut, would inevitably die. The huts consisted of one room and a hall. Colloquially they were called "Stalinets". In many Polish villages, such "stalinets" survived until the 1980s. And in one of them, in the Green Grove, a museum has now been organized. A few kilometers from Zielony Gaj there was the Kazakh hall (rural commune) Żarkain. Local people immediately came to greet the settlers. Though it was a time of famine, they arrived, as the tradition of the steppe dictated, not empty-handed. They brought pancakes (lepioszki) and kurt (round, dried sheep's milk cheese). For Polish children exhausted by under-eating and a long journey, these steppe gifts were like manna from heaven.

It snowed at the end of October and the winter of that year was extremely severe. In December, snowstorms blew snow up to the roofs. You could only get out after digging a tunnel in the snow. In order not to freeze, bitter weeds were dug out from under the snow and burned in furnaces. In the first period, people ate products from the stocks and gifts of the Kazakhs. Later, a bakery was opened in the village and each family began to receive some rye grains so that the village would not become extinct. The people went to work in the nearby old Ruthenian settlements of Daszka-Nikołajewka and Nowobriłowka. There they also exchanged clothes and household appliances for food.

In the spring it became easier. They began to plow the soil, organized the collective farm "Commune Star". Emanuel Oczkowski graduated from tractor-harvester courses and started working with mechanical equipment in the spring of 1938. He plowed in spring, and in autumn he switched to a combine. The Poles worked diligently and the collective farm was developing. At the beginning of the war, there was already a school, nursery, hospital, shop and club in Zielony Gaj. People gradually moved from the Stalinets to houses made of burnt brick. They established their own farms and planted gardens. In general, life began to normalize.

Then it was June 22, 1941. The people of Zielona Góra were informed of the beginning of the war, and although Poles were considered untrustworthy, some of them were drafted into the active army, and some to work at the front. During the war, out of 1,400 people living in the village, 92 men went to the front. The front of Emanuel Oczkowski was the kolkhoz fields - soldiers had to be fed with bread. Day and night he did not let the combine's rudder or the tractor steering wheel out of his hands. Until the end of his days, he practiced one of the most peaceful jobs in the world - he remained a farmer. In 1955, according to the government order, for almost a month, together with his combine, he took part in the harvest in the Tjulkubassy region, South Kazakhstan oblast, meeting the daily threshing standard of 177%, for which the management of Tjulkubassky POM gave him a written thank you. In 1958 he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor for his dedicated efforts, of which he was very proud.

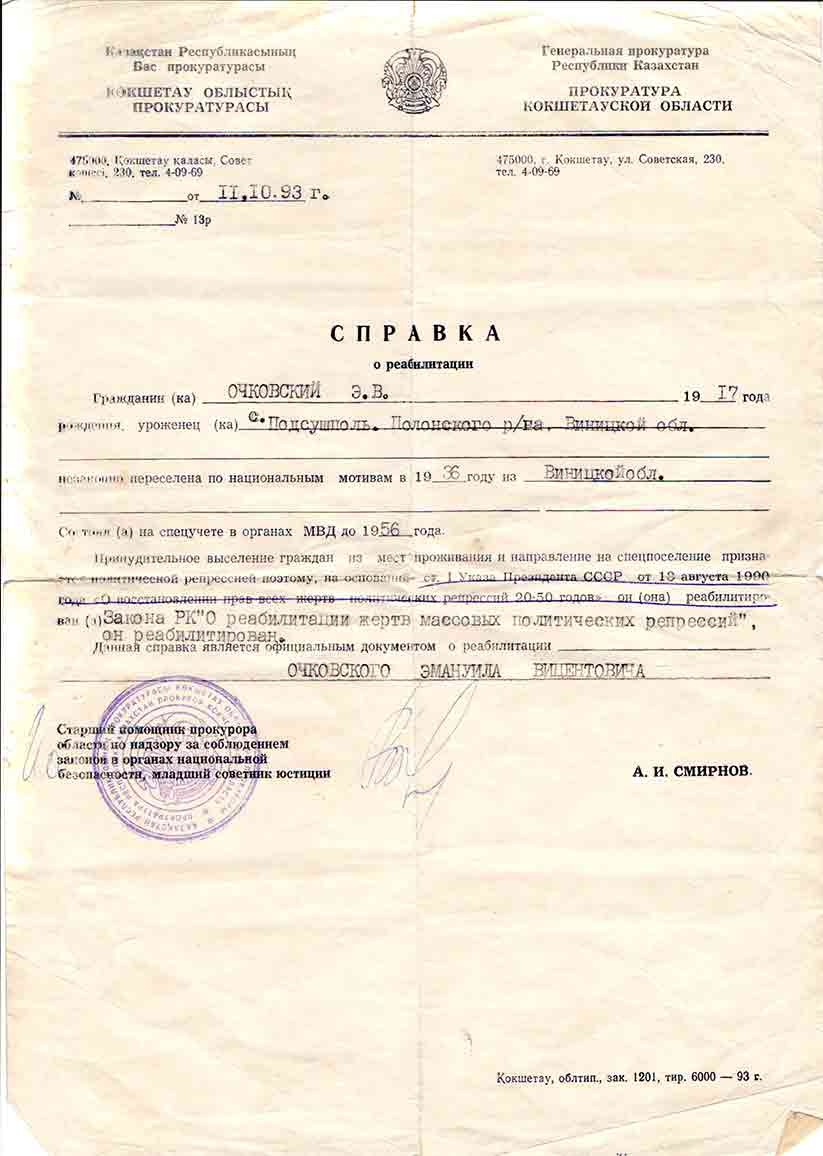

After the end of the war, Poles were again considered untrustworthy. Until Stalin's death, they were under administrative supervision. They were forbidden to leave the village borders. They had to report to the commander regularly. It only improved with the advent of the "Khrushchev thaw". Although the restrictions on Poles were lifted, in 1956 Poles were still under the supervision of administrative bodies and the NKVD. It was not until 1959 that Poles began to be issued passports and they became full citizens.

Emanuel Oczkowski, son of Wincent, has lived a long and dignified life, and passed away in 2002. Together with his wife, Adela Tofiljewna, he raised his daughter, my mother - Ludmila Czerwińska, who received a good education and worked for many years as the head of the school teaching department. Together with my dad, Czesław Czerwiński, she raised us to be Poles.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz, with the assistance of Google Translate.