On September 17, 1939, after the aggression of the Soviet Union against Poland, the Polish government and the commander-in-chief, Edward Rydz Śmigły, evacuated to Romania, with which Poland had friendly relations, in order not to be captured and forced to sign the surrender. Unfortunately, the political circumstances changed and the Polish authorities, along with the president and the commander-in-chief, were interned there.

In order to ensure the legal and international continuity of the Polish state, it was necessary to find new members of the government who were beyond the reach of the aggressor. Such successors could be diplomatic workers in friendly France. One of them was Władysław Raczkiewicz. Although he evacuated together with the government and the president, on September 25 he found himself in Paris. Initially, president Ignacy Mościcki appointed General Wieniawa-Długoszewski as his successor, but after his resignation, he appointed Władysław Raczkiewicz.

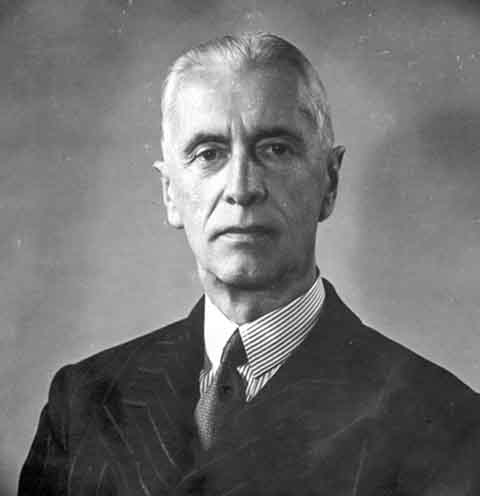

Władysław Raczkiewicz (1885-1947)

Władysław Raczkiewicz (Source: Wikipedia)

The newly appointed president had quite a wealth of political experience. He was born in Georgia in Tsarist Russia. He was a lawyer by education. During World War I, he actively fought for Poland's independence, and after regaining it, he performed various social and state functions, including several times that he served as a voivode, president of the World Union of Poles from Abroad, senator, Speaker of the Senate and Minister of Internal Affairs in four governments of the Second Polish Republic.

On September 30, 1939, he assumed the duties of the first president of the Republic of Poland in exile, and on October 1 in Paris, he appointed a government in exile composed of:

- Władysław Sikorski - Prime Minister, Minister of Military Affairs, Minister of Justice,

- Stanisław Stroński - Minister - Deputy Prime Minister,

- August Zaleski - Minister of Foreign Affairs,

- Adam Koc - Minister of the Treasury, Minister of Industry and Trade.

After the establishment of the Polish government-in-exile, he handed over a large part of his powers to the commander-in-chief of the Polish armed forces, General Władysław Sikorski.

The continuity of Poland's state institutions was, contrary to the declarations of Germany and the USSR, internationally recognized throughout the entire period of World War II.

In November 1939, the seat of government was moved from Paris to Angers. On December 9, 1939, President Raczkiewicz established the National Council of the Republic of Poland, which was to act as parliament. It consisted of 12-24 members. It was headed by Ignacy Paderewski. On December 18, the government issued a declaration outlining the most important goals of activities in exile. It defined the Third Reich as the main enemy of Poland, announced the struggle for liberation and the creation of an Army in the West, and generally defined the shape of post-war Poland.

One of the most important problems was the expansion of the Polish Armed Forces in the West. Agreements were being signed with the British and the French, it was planned to create an army of 100,000. Not all plans were implemented, but in the spring of 1940, the 1st Grenadier Division, the 2nd Foot Rifle Division, the Independent Podhale Rifle Brigade, and the Polish Air Force were established.

After the defeat of France, the Polish government accepted the invitation of Prime Minister Churchill and on June 17, 1940, he evacuated to London, where he continued to act as a representation of the Polish state.

On August 5, 1940, a Polish-British military agreement was signed, thanks to which in 1942 it was possible to create the Independent Parachute Brigade and the 1st Armored Division. The government was also involved in the construction of the Polish Underground State. General Sikorski established the Union for Armed Struggle, later renamed the Home Army, which operated until January 19, 1945, until its dissolution by General Leopold Okulicki.

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the USSR, which was the decisive event for the fate of World War II. Great Britain offered the USSR an alliance. Therefore, Polish-Soviet negotiations were also initiated, restoring (albeit briefly) diplomatic relations between Poland and the USSR.

The consequence of these negotiations was the signing of the Sikorski-Majski Agreement on July 30, 1941. The provisions of the treaty included mutual aid against German forces, permission to establish a Polish army in the USSR, the annulment of the Soviet-German agreements concerning Poland before 1939, and the restoration of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The signed treaty caused a serious crisis in the government. President Raczkiewicz was against its signing. The treaty was accused of unconstitutionality and the lack of a declaration by the USSR regarding the restoration of the border defined in the Treaty of Riga. Foreign Minister August Zaleski resigned, and the crisis led to a split in the foreign coalition.

Władysław Raczkiewicz did not have much influence on the course of political affairs. He made decisions under the influence of the British government or on the suggestion of Prime Minister Churchill.

On July 5, 1945, as a result of the decisions at the Yalta Conference, the Polish Government-in-Exile lost the recognition of Great Britain and the United States. This meant the takeover of Poland's property and representation on the international arena by the Provisional Government of National Unity in Warsaw subordinated to the communists. As a result, the President of the Republic of Poland and the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile lost the status of a subject of international law, although they continued their activities until the first general presidential election in Poland in 1990.

Władysław Raczkiewicz performed his function until his death in 1947.

In his political will (in 1945) he appointed August Zaleski as the successor of the head of state. The rejection of the previously agreed candidate, the former Prime Minister Tomasz Arciszewski from the PPS, led to the party's secession from the government and resulted in a long-lasting disruption of Polish independence emigration in the post-war period.

August Zaleski (1883-1972)

August Zaleski (Source: Facebook, colorized by M. Szponar)

August Zaleski was the President of the Second Polish Republic in the years 1947-1972. He graduated from economics at the University of London and was preparing to work as a scientist.

In 1915, he undertook the mission of convincing the British about the purposefulness of J. Piłsudski's actions. In the interwar period, he was the head of the Polish mission in Switzerland, a member of the Polish delegation to the Paris peace conference, and after the May Coup, until 1932, he was a minister of foreign affairs, a deputy, and a senator.

In 1939, he became the minister of foreign affairs of the Polish government-in-exile. His assumption of the office of president met with great resistance from the opposition. After a seven-year term, he remained in office, which resulted in the refusal of their obedience by many politicians (including Gen. Anders and Gen. Bor-Komorowski) and the establishment of the Council of Three — the collegial head of state in office until the death of President Zaleski. In 1972, the Council of Three was dissolved, and Stanisław Ostrowski was appointed the president by A. Zaleski.

Stanisław Ostrowski (1892–1982)

Stanisław Ostrowski (Source: Wikipedia)

Stanisław Ostrowski was a doctor, political activist, legionnaire, a member of the defense of Lviv in 1918, a participant in the Bolshevik war of 1919-1921, a member of parliament. In the years 1936–1939 he was the president of Lviv. He organized and took an active part in the defense of the city in September 1939.

After the September campaign, he was arrested by the NKVD. Until 1941 he was a prisoner of Soviet labor camps in Siberia. After the amnesty in 1941, he joined the Polish Army in the USSR, commanded by General W. Anders. Evacuated to the Middle East, he followed the combat route of the 2nd Polish Corps. After the war in Great Britain, he was active in numerous émigré organizations, including the Polish government in exile.

In 1971 he was appointed the successor of the president-in-exile. He took office in 1972, after the death of August Zaleski, and held it until 1979. He led to the unification of the Polish emigration, which had been dispersed since 1954, and the self-liquidation of the second political center, which was the Council of Three. His successor was Edward Raczyński.

Edward Raczyński (1891-1993)

Edward Raczyński (Source: Wikipedia)

He came from an aristocratic family related to many noble Polish families.

He studied law in Leipzig, and obtained a doctorate in law at the Jagiellonian University. He also studied at the London School of Political Sciences. In 1919 he started working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He has worked in institutions in Denmark and Geneva. From 1934 he was the Polish ambassador in London. He worked closely with General W. Sikorski and President Raczkiewicz.

In the years 1941-1943 he was the Minister of Foreign Affairs. He signed the Polish-British alliance treaty on behalf of the Polish government. Based on the documents brought in the form of microfilms to London by the courier Jan Karski and confirmed by his testimony, Edward Raczyński prepared and, on December 10, 1942, presented to the Allies a detailed report on the Holocaust, which was issued as an official note of the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile addressed to the governments of the signatory countries of the United Nations Declaration.

Raczyński's Note was the world's first official report on the Holocaust to inform the world public about it. Raczyński also personally edited the government's statement after the discovery of the graves in Katyn in 1943 and sent a request to the International Red Cross for an explanation of the crime.

In the years 1979–1986 he held the office of the President of the Republic of Poland in Exile, and after the end of the 7-year term, he handed over the office to Kazimierz Sabbat.

At the end of 1990, he founded the Raczyński Foundation in Poznań and donated the palace, the park, and the museum collections in Rogalin to it. Rogalin is also his eternal resting place.

Kazimierz Sabbat (1913-1989)

Kazimierz Sabbat (Source: Wikipedia)

In 1939, he graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Warsaw. He was a scout in the Second Polish Republic. After a short service in the Navy, he was assigned to serve in the brigade of General Stanisław Maczek, with which he reached Great Britain. He entered the reserve in 1948.

He continued to work in the scouting and the Association of Polish Combatants. In the years 1976–1986 he was the prime minister of the government, and on April 8, 1986 he took the office of the President of the Republic of Poland in Exile. He visited the Polish Armed Forces in the West scattered around the world. He died suddenly on July 19, 1989 in London.

After his death, the last president of the Second Polish Republic was Ryszard Kaczorowski, about whom we will be writing more.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.