Gerhard Schröder, in an interview with The New York Times (NYT) entitled "The Former Chancellor Who Became Putin's Man in Germany," referring to his unsuccessful mediation attempt in Moscow, said: "Putin is interested in ending the war. But that’s not so easy. There are a few points that need to be clarified." [1]

Two issues require clarification here: how to understand the term "ending the war", and what exactly "needs to be clarified". The statement of a German politician, that clearly promotes Putin's plans and attitudes, thus defines Schröder, a significant Western politician, as a kind of propaganda mouthpiece of Putin himself. At the end of the interview, Schröder himself tanks, concluding characteristically: "I have no regrets."

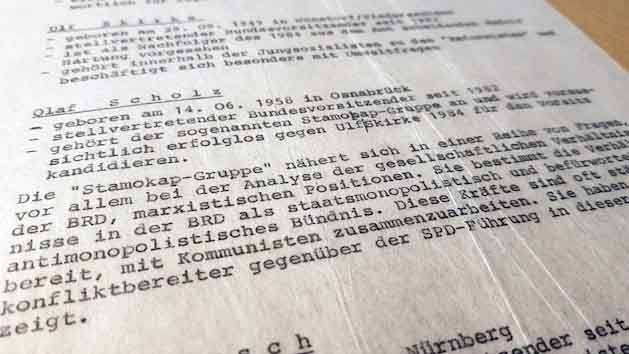

Gerhard Schröder in 2016 (Source: Wikipedia)

This interview is "unusual," to say the least, as the former chancellor and now a lobbyist for Russian companies is once again refusing to break up with his friend Vladimir Putin. On the contrary, Schröder makes it clear: "You can’t isolate a country like Russia in the long run, neither politically nor economically." In this interview, Schröder does not believe Putin is responsible for Russian war crimes in Ukraine. "That has to be investigated." However, "he did not think those orders would have come from Mr. Putin, but from a lower authority." [1]

At the end of the interview, he announces that he will not give up his activities on behalf of Russian energy companies, which has met with severe criticism even from within his own party. He would only be able to resign from his position if Putin really shut off the gas valve to Germany and the European Union. But that's not all: the annual general meeting of the Russian energy giant Gazprom will be held soon in June and Schröder is to be elected to the supervisory board there. In the above-mentioned interview, the former chancellor left the question of whether or not he would run for the position open, while also making it clear, that he did not see any problems with his close relations with the Kremlin: "I don’t do mea culpa, it's not my thing." [1]

Reaction of German circles to an interview in The New York Times

The repercussions after the statements in the NYT did not let themselves to be awaited for too long, especially in political circles.

- The co-chair of the SPD, Saskia Esken, reacted immediately to his interview. She demanded that the former chancellor give up his party membership.

- The local SPD unions in Heilderberg, Waiblingen and Leutenbach have already officially filed a motion to remove the former chancellor and friend of Putin's from the party.

- The Prime Minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Hendrik Wüst, said: "The SPD's procrastination to cut itself off from Schröder may turn out to be a fateful memory from the first phase of Chancellor Scholz's rule." Wüst demanded consistency from the SPD leadership after Schröder's recent statements.

- SPD MP Michelle Münterfering wrote on Twitter: "Gerhard Schröder is damaging our country, our international reputation - and especially the SPD."

- CDU's Schleswig-Holstein lead candidate Thomas Losse-Müller said Gerhard Schröder no longer played any political role. When he speaks, he "acts as a paid lobbyist for Russian entrepreneurs."

Critical words after the appearance of the interview in the NYT were not spared by other politicians who stood in opposition to the SPD, either. Recently, Bundestag vice-president Wolfgang Kubicki (FDP) in an interview with Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland (RND) questioned the equipment of the state-funded Schröder offices by saying. "I think there is a need for a fundamental discussion about the extent to which these past-chancellorships must, in case of doubt, be fully filled for decades."

It has to be said that even before this eventful interview appeared in the American daily, voices of indignation had multiplied at Schröder's opportunistic links with Putin. The mayor of Kiev, Vitaly Klitschko, in an interview with "Bild", suggested that the former German chancellor move to Moscow.

Also in everyday life in Germany, there were more and more expressions of indignation — if only in a symbolic way — against Schröder's opportunism, e.g. the Borussia-Dortmund sports club annulled his honorary membership; in the SPD store in Berlin, cups with his likeness were thrown into the dustbin; and some party comrades the SPD called Putin, whom he himself described as an "flawless democrat" — a war criminal. According to a poll, 75% of Germans are demanding that Schröder's pension be annulled if he does not quit his job in the management of Russian state-owned enterprises. His office employees have already quit.

How did it all start? How is it manifested today?

In the late seventies, when Gerhard Schröder was the chairman of the socialist West German youth organization Juso (1978-80) and editor-in-chief of the magazine with a strong "red" profile, "Sozialistische Tribüne" (The Socialist Tribune), he conveyed his pro-communist convictions, which he expressed in the words: "Yes, I am a Marxist. " In a discussion with the editors of the Göttinger Kreis, which he thought was not "socialist" enough, he put it this way: "If you are a Marxist force in the Young Socialists and in the party — then the class enemy can be calm: revolution will wait."

In May 1980, Gerhard Schröder, still chairman of Juso, received Egon Krenz, the head of the communist youth federation in the GDR, on a visit to the Federal Republic for the first time. It was then agreed that the FDJ — a youth organization with a purely communist profile in the GDR — and Juso would establish official relations.

As Chancellor of the Federal Republic (1998-2005), he maintained very close contacts with the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin. Gerhard Schröder received Vladimir Putin for the first time a few weeks after the latter's election as president, in 2000. He was impressed by Putin, with whom the West had high hopes for reforms in Russia at the time.

In 2001, Putin gave a speech, in German, at the Bundestag. The president of Russia speaks German fluently — after all, he was stationed as a KGB agent in the GDR. So Schröder and Putin "exchange views fluently." Since 2001, contacts have deepened.

Gerhard Schröder feasts with Vladimir Putin in Moscow, in April 2002 (Source: Wikipedia)

At a personal level, they celebrate holidays together (Schröder — Orthodox Christmas) and birthdays (Schröder invited Putin as a guest to his 60th birthday celebration in Hanover; Putin came, bringing the Cossack choir from Russia). There have been many opportunities to establish "mutual relations".

The first results of these relations took place in September 2005, when the then-Chancellor Schröder and Putin formally signed an agreement about the construction of the Baltic pipeline. The Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline was to transport natural gas from Russia to Germany. In 2017, Schröder became chairman of the supervisory board of Nord Stream AG, 51% of which is owned by Russian Gazprom.

When Russia annexed the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in 2014, Gerhard Schröder called for "leniency" for the violation of international law by the Russian side! And the recent speeches, to mention the NYT interview once again, confirm the ex-chancellor's absolute devotion to the cause of his guru - Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.

At the time of Russia's aggression against Ukraine, the former chancellor reacted like this: "Let Ukraine stop rattling sabers" — and he remains loyal to Putin.

Where does this loyalty to the Russian autocrat come from?

Schröder's past is not well known. Already in 1980, as chairman of the socialist youth organization in the German Federal Republic, Juso, he announced his above-mentioned life credo, to which he remains faithful: "Yes, I am a Marxist." Invited to numerous meetings by the East German authorities, he said: “I am going there because I was interested in this country, and also because I know many politicians from the time when I was president of Juso. Besides, I am invited by Erich Honecker, whom I consider to be an extremely interesting man. "

As Chancellor, along with the French President Jacques Chirac, Schröder opposed the 2003 Iraq War and refused military support for the operation. This opposition was in line with the views of the young socialists (Juso), which he headed and caused a cooling down in relations between the US and Germany, and tarnished Germany's reputation as the most important and closest ally of the US. And yet, that was what Schröder's contacts with the German-eastern — read: Moscow-based — rulers of this part of Europe were all about.

Great friendship (Photo: Alexei Druzhinin, Source: Reddit - reddit.com/r/ukraine)

The daily "Bild am Sontag", in 2005, citing American intelligence circles, reported that Schröder's person had become "of interest" to the US intelligence. In the background, there were close contacts with Putin and Schröder's rapid career in the Russian energy industry.

The Süddeutsche Zeitung writes, citing sources in the US administration and the NSA, that Schröder's position on the preparations for the war in Iraq and the Americans' fear of a split in NATO were the reasons for his inclusion on this list. The newspaper quotes the opinion of an anonymous person who knew the circumstances of the wiretapping operation: "We had reason to believe that Schröder was not contributing to the success of the alliance." Schröder refused to join the war with Iraq and strengthened contacts with other countries (Russia and France) rejecting the intervention.

According to the NYT, Gerhard Schröder is being rewarded with one million dollars a year by gas companies controlled by Russia. It became a symbol of German-Russian politics in the 21st century. For how long? Are we dealing with an economic opportunism — or with an adversarial agency?

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.