The issue of reparations for Poland for losses suffered in World War II is a contemporary topic that is gaining more and more attention of society. The report prepared by the Polish parliamentary team consisting of 30 scientists - historians, economists, property appraisers - estimated the total material losses that Poland suffered as a result of German aggression and occupation at PLN 6 trillion, 220 billion, 609 million (USD 1,532,170 million).

However, they do not include moral losses, the valuation of which is impossible because there is no measure to assess human pain after the loss of loved ones, especially the pain of parents after the loss of children. This category of unaccounted for German crimes against the Polish nation includes the abduction of Polish children, whose number (estimated) is 200,000, of whom just over 30,000 returned to Poland.

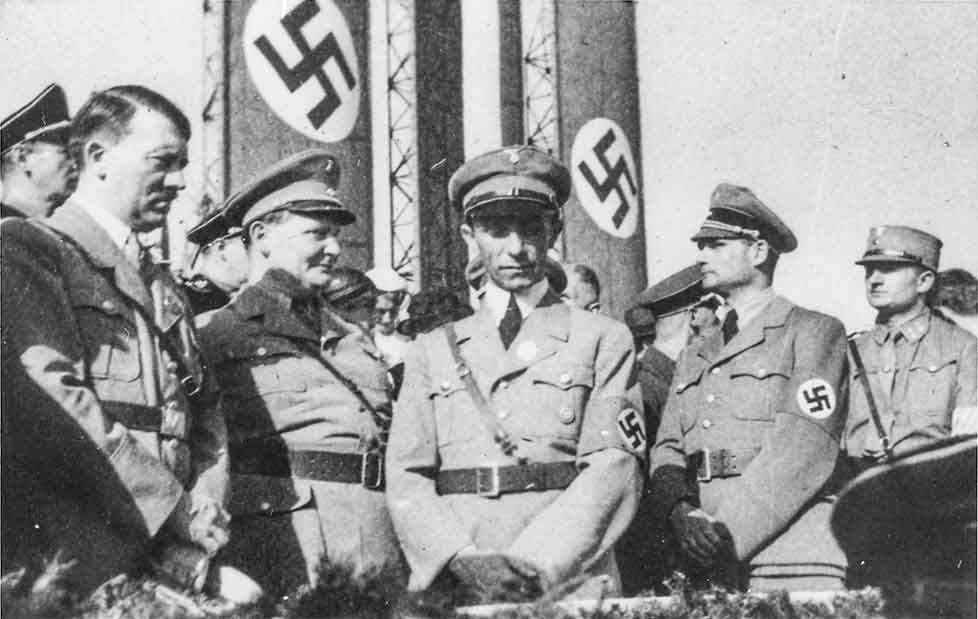

Philosophical and systemic programs of Nazi Germany regarding demography

What happened during World War II in Eastern Europe was planned by the Germans in advance and supported by an appropriate philosophical doctrine. Germans have always felt that they were a better nation than others. This is perfectly expressed in their song "Deutschland uber alles" (Germany above all). They did not come to terms with the defeat suffered in World War I and in the interwar period they developed plans to conquer "living space", conquer the whole of Europe — the lands from Lisbon to the Urals — and develop them economically and socially.

The German General Plan for the East assumed the displacement of most of the local Slavic population, whom Nazi racial policy defined as "lower Slavic races – subhumans", and the settlement of Germans and Germanic people from other parts of Europe in their place. This plan was implemented in parallel based on the Wehrmacht's victories in the east and the assumptions of the main goal of World War II, which was to be German domination of the world. The development of the acquired "living space" required appropriate human potential, both in the form of leaders and labor, and the related appropriate demographic policy. The government was to be managed by "pure-blooded" Germans, and the workforce was to be citizens of the conquered nations.

Appropriate plans to increase the number of German citizens of the pure "Aryan race" began to be developed already in the interwar period. One of the implementers of the plan was the Lebensborn association, established in December 1935 on the initiative of Heinrich Himmler. It was intended to create a system of care for "racially valuable" families and the children of these families (both married and illegitimate). As a result of these actions, children became the property of the state. Lebensborn's activities, however, did not bring about the expected quantitative increase in the number of "racially valuable" German citizens, but became the main executor of the planned abduction of Slavic children, in which the largest number were Polish children.

Kidnapping operations

Resettlement actions on Polish lands began at the end of 1939 and lasted until the summer of 1943. The first ones concerned displacements from the lands occupied by Germany, from Greater Poland. The next ones took place in the Lublin region, because the land was the most fertile there and German families living outside the Reich were being relocated there. The Eastern Plan included the physical liquidation of Jews, Roma and enemies of the Reich, leaving several million Poles as a labor force. The rest of the displaced population was sent to work in the Reich or to concentration camps. In 1940, Heinrich Himmler developed preliminary guidelines for a program of abduction of "racially useful" children suitable for Germanization. "Obtaining" Polish children took place in many ways. Children were abducted by force, often using tricks. Children were kidnapped when their mothers were away from home, children were taken from families convicted of anti-German activities, orphanages were liquidated, and children were separated from their displaced parents.

Abduction of Polish children during the displacement operation in the Zamość region (Source: Wikipedia)

The tragic fate of the children of the Zamość region deserves special memory. In pilot actions in 1939 and mass displacements lasting only a few months (from November 1942 to March 1943), 110,000 people were deprived of their belongings, shelter, health and a large part of their lives, including 30,000 children. A separate action as part of the child abduction program was the Heuaktion special operation carried out in 1944 by the German Army Group "Center" and the 9th Army on the territory of Ukraine and Poland, during which 40,000-50,000 kids were captured. Of all the victims of child abductions, most came from Poland.

The fate of abducted children

The operation of abducting "racially valuable" Polish children included those up to the age of 12. In special transit camps, they were subjected to racial qualification tests (they had to have blue eyes, blond hair, appropriate skull size, etc.), and the further fate of those selected in terms of race depended on the activities of Lebensborn. In accordance with the instructions of the Reich Main Office for the Strengthening of Germany of February 19, 1942, the association carried out a Germanization campaign.

The "baptism" ceremony of a child adopted by a German family from the Lebensborn center (Source: Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv)

After preparing new documents (change of names, personal data, family histories...), children up to the age of 6 were placed in German adoptive families, and from the age of 6-12 they were sent to appropriate schools and subjected to Germanization. Racially unsuitable children were transported to concentration camps in inhumane conditions and killed en masse.

Post-war fate of abducted Polish children

Child abduction was recognized by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg as the crime of genocide. The 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, in Article 2e, classifies as genocide the forced transfer of children of members of a group to another group. The 1948 UNESCO conference, held in Trogen, Switzerland, recognized the abduction and extermination of children as a crime against humanity.

After the war, as a result of investigation, children were found in various places, in Germany, Austria and even Spain. The search was made more difficult by the fact that Lebensborn employees destroyed most of the files and documentation.

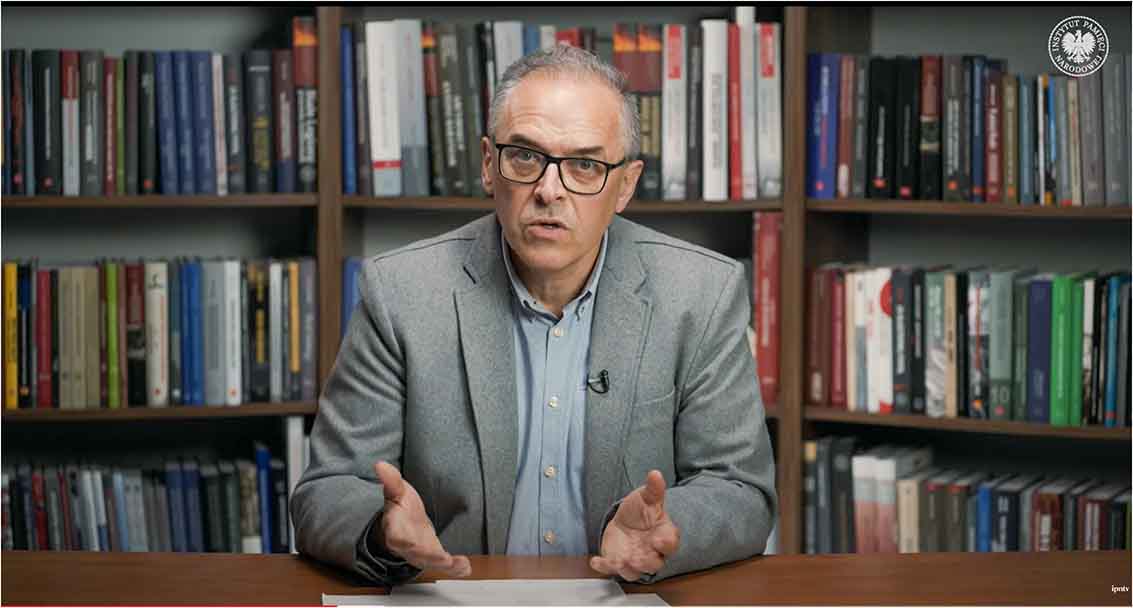

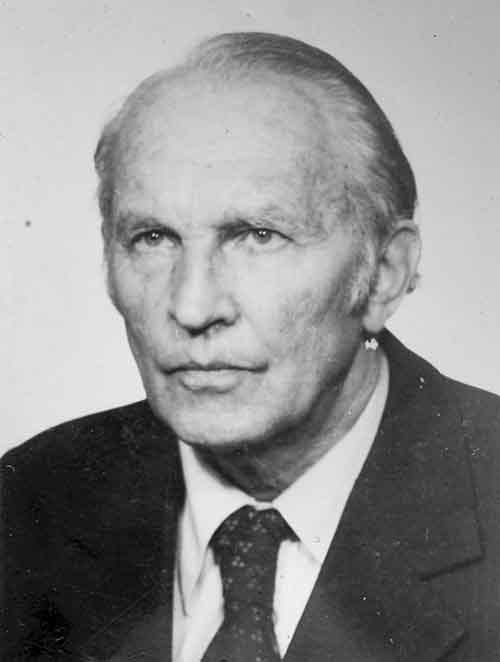

Revindication attempts - Roman Hrabar's team

After the end of the war, great work of the recovery of Polish children was carried out by the Polish lawyer Roman Zbigniew Hrabar (1909 - 1996), born in Kołomyja, and the team he established. While he worked at the Katowice voivodeship office, he was responsible for organizing social welfare for the people of Silesia. One of the forms of his activity was the organization of an information system for those looking for their families. During this work, he encountered the problem of missing Polish children for the first time in post-war Poland. He became more interested in this problem because documents began to appear about the planned abduction and Germanization of Polish children carried out by "Lebensborn" not only in Silesia, but also in all Polish territories occupied by the Germans.

Attorney Roman Hrabar (Source: Polish Bar)

Hrabar became the coordinator of work throughout Poland. In March 1947, he became the Polish Government's Plenipotentiary for the Recovery of Abducted Children. To accomplish this mission, he organized a team with which, in the spring of the same year, he went to Heidelberg, to the UNRRA Headquarters, in the American occupation zone. There he obtained accreditation as a Senior Child Research Officer with the Polish Red Cross (PCK). During his mission, he was lucky to meet Eileen Blackley, a good friend of the US president's wife - Eleanor Roosevelt, and Dr. Edmund Schwenk, one of the prosecutors preparing the so-called The 8th Nuremberg Trial, in which 14 high-ranking SS members and civilian officials were accused of participating in the kidnapping of children from the areas occupied by the Third Reich, not only Polish ones.

Thanks to the testimonies of abducted children found by Hrabar's team — Alina Antczak, Barbara Mikołajczyk and Sławomir Grodomski-Paczesny — at the 8th Nuremberg trial, thirteen defendants were sentenced to long prison terms.

The first place to look for Polish children was Regensburg in Bavaria. At the UNRRA headquarters there, E. Blackley found documentation regarding 4,000 abducted Silesian children. Hrabar's efforts resulted in the first transports with small repatriates reaching Katowice in late spring 1947.

The Polish lawyer, in the process of fighting for stolen Polish children, encountered many formal obstacles from the authorities of the Western occupation zones in Germany. First of all, the Polish side was required to prove that a given child had been "stolen" from Polish territory. The children were found in various places far from Poland, their family documentation was destroyed or falsified, time passed, circumstances changed and the abduction victims were no longer the same children. Children over 16 years of age were also required to submit declarations of their willingness to return to Poland. The victims, abducted in early childhood, did not remember their biological parents, did not know the Polish language, and often acclimatized relatively well to German families who surrounded them with care and love and did not want to return to places and people alien to them. To this day, the victims of the robbery who are still alive struggle to accept their identity. It happens that siblings belong to two nations out of no fault of their own.

In the summer of 1947, as a result of the developing idea of the "Iron Curtain", the US government decided to liquidate the child search department at UNRRA. E. Blackley's intervention with Eleanor Roosevelt and the mayor of New York — Fiorello La Guardia — allowed the operation of this department to be extended for another year.

Despite Hrabar's efforts, cooperation with the authorities of the English occupation zone was deteriorating. In August 1950, the British authorities decided that the abducted Polish children in their territory were to remain with adoptive German families or be given up for adoption in Great Britain, even though Hrabar's team had by then identified the names of 6,500 Polish children.

As a result of the increasingly tense relations between the Allies and the Soviet Union (the so-called "Cold War"), by August 31, 1950, the Polish Red Cross delegations in Germany finally ceased to operate. 70% of the abducted children identified by that time were Poles. R. Hrabar's team managed to bring back only 15-20% of the children (approx. 33,000, including 20,000 from the Soviet zone, 11,000 from the western zones in Germany and approx. 2,000 from Austria; approx. 170,000 remained outside Poland).

After returning from the mission, R. Hrabar practiced law, but as a member of the Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes, he was still one of the few in Poland to provide help to people looking for their children. He also wrote several books on this subject, which are the substantive basis for this topic to this day.

80 years have passed since the height of the abduction of Polish children by Nazi organizations. We need to remember those tragic moments and the heroic activities of attorney Hrabar. No amount of reparations can compensate for those wrongs, even time cannot heal the wounds, but we must prevent that history from repeating itself.