Historical truth is an objective reality, existing regardless of the situation that could distort it. It is something that is happening today, or has happened in the past. It is the responsibility of each of us to investigate, learn about, and be faithful to it. Very often historical truth falls victim to politics, is twisted, manipulated and replaced with lies. The generation that knew the facts is dying out. There is only hope that the documents it left behind will help in finding out the truth.

Recently, there has been talk of the martyrdom of one chosen national group during World War II, ignoring other people, as if the suffering of one nation was more important than others. This way of thinking blurs the truth about those who likewise suffered cruelty, and yet their lives were equally important. The distortion of historical facts in order to profit has irreversible consequences. People are getting tired of hearing propaganda. As a result, the guilt of those who have committed crimes against humanity is diminished. The degeneracy of the torturers must be kept in mind so that no more such acts are ever permitted.

The Germans occupying Polish lands during World War II set themselves the goal of liquidating not only the Polish state, but also the nation. They planned that, within 10 to 20 years, the Polish territories would be completely cleared of people of Polish origin and settled by German colonists.

Part of Poland was annexed to the Third Reich, and in the rest, the General Government was established under the rule of the occupant. Poles living in the General Government were to serve only as free labor. Persecution of the population, elimination of the Polish intelligentsia, clergy and people of culture became a daily reality. Round—ups, street executions, and prisons did not satisfy the persecutors. The German torturers looked for new solutions for an even faster extermination of Poles. For this purpose, in 1939, they started to create a system of concentration camps.

One of them was the camp in Oświęcim, called Auschwitz by the Germans. It was established in 1940. Within four years it became the largest genocide site in human history. Until the end of the camp's existence, around 440,000 prisoners were officially registered. In total, over a million people were murdered, often not covered by any records. The immediate cause of the opening of this hell on earth was the increasing number of Poles detained in German prisons.

The camp consisted of several parts. The first was Auschwitz I, established in 1940 on the premises and in the buildings of pre—war Polish military barracks. The second and largest of the entire complex, Auschwitz II—Birkenau, was established in 1941 in the village of Brzezinka, 3 km (2 miles) away from Oświęcim. In Birkenau, the Germans built most of the devices of mass extermination. The third was Auschwitz III, where in the years 1942—1944, in over 40 sub—camps, the slave labor of prisoners was used with incredible cruelty. They were mainly employed in various types of German industrial plants, as well as agricultural and livestock farms. The largest of them, called Buna, was located 6 km from Auschwitz and established in 1942 at the Buna—Werke synthetic rubber and gasoline plant. To the German concern IG Farbenindustrie, which built these plants, the SS supplied prisoners for forced labor.

The entire camp, with an area of over 40 square kilometers, was isolated by the Germans from the outside world and surrounded by a barbed wire fence. The SS crew diligently guarded the perimeter and the surrounding area. Local people living in the vicinity of the created camps were displaced. Their homes were demolished or given to SS cadres and their families. The Germans ruthlessly kept secrets about the crimes they had committed. Camp censorship applied to everyone. For a long time the world did not know — or did not want to know — what was happening in Auschwitz.

The prisoners, numbered 1–30, were German criminals. They were a group of functional prisoners: kapos, block supervisors, etc. They arrived in May 1940. Their psychopathic tendencies and particular cruelty were used to maintain order and discipline in the camp.

The first Polish prisoners, referred to as political, in the number of 728, were brought to Oświȩcim on June 14, 1940 from the camp in Tarnów. In this group, selected for transport, there were, among others, members of the resistance movement, political and social activists, as well as persons detained while attempting to illegally cross the border in order to join the ranks of the Polish Army in France. It was the beginning of the mass extermination of Poles and other nations at Auschwitz.

Three 16–year–olds lived in the General Government, near Warsaw, in the vicinity of Pruszków. They knew each other from school. They went to clay pits in Żbików together, served to mass in their parish, belonged to the scouts. They met in Potulicki Park to talk about literature and politics. The outbreak of the war thwarted their plans for the future. Education in gymnasium was forbidden. In the eyes of the occupant, the role of Poles was limited only to the service of the German Reich as an unskilled labor force. The young people began to think about the fight for the liberation of Poland. In 1940, they joined the underground organization of the Polish Defense Corps (KOP). Some of their colleagues from the KOP have already managed to get to Hungary with the hope of joining the Polish Army. Following their example, they began planning the crossing of the border. Their families were informed about everything. Their older brothers operated in the underground, they were no strangers to conspiracy. The mothers, terrified by their idea, went to the parish priest for advice. Indeed, it was all about their age. They were still children. Two of them were the youngest in the families. They heard from the priest that "the homeland first, and then the family."

Having no other arguments, they agreed. They gathered what they could, money and a little food, and blessed them upon departure. In November of the same year, the boys hid in a freight train going south. In the vicinity of Cisna, they were handed over by the Ukrainians to the hands of the Germans. The denunciators demanded that they be shot to receive the prize. Somehow they managed to escape death. A Jewish family of eight who was shot on the spot was hiding on the same train.

It is not known why they survived, maybe they were dirty with the flour in which they were hiding they amused the Germans with their appearance, or maybe the proverbial German compliance with the regulations saved them from immediate death. As minors, they were taken to a prison in Sanok. On November 7, 1940, their youth ended.

In prison, they were treated like everyone else. They were interrogated and beaten. They were sentenced to five to ten years of forced labor for the German Reich.

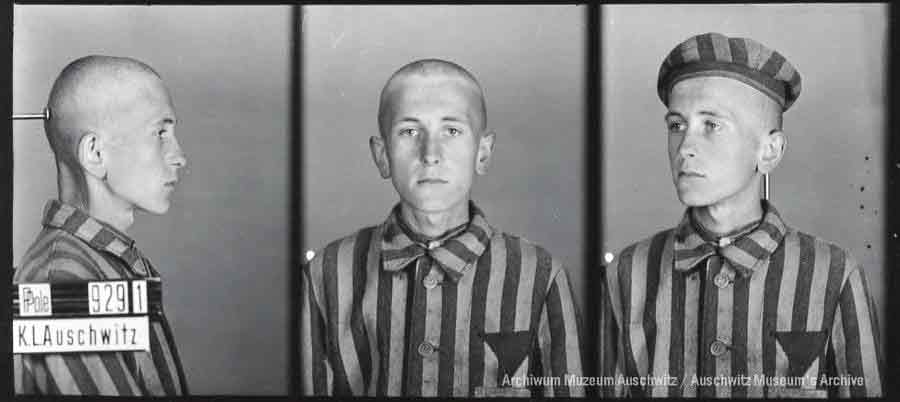

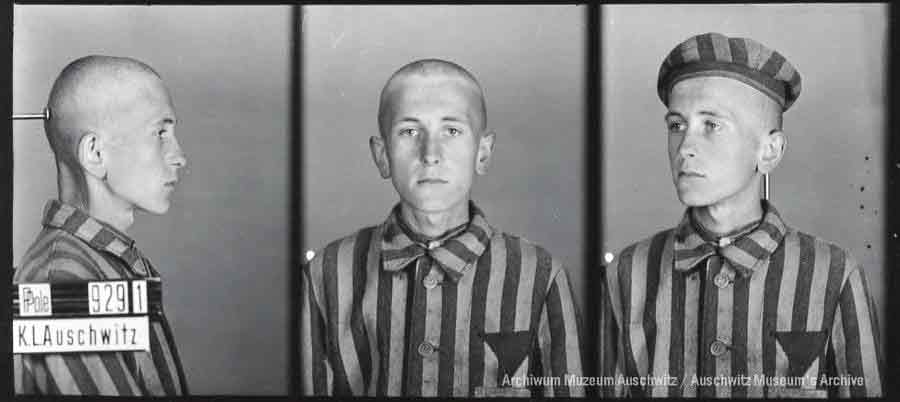

On January 10, 1941, they were transferred to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. The oldest of them, Bolesław Łukasiak, camp number 9290, called Bolek, was 17 years old. The others, Zdzisław Trawiński, camp number 9291, and Romuald Hałaczkiewicz, number 9289, known as Aldek, were sixteen years old. They were in the same barrack for the first half of the year. Then they were separated and transferred to different barracks.

Bolesław Łukasiak, a.k.a. Bolek

Bolesław Łukasiak

Bolek, on the second day of his stay in the camp, sent a letter to his mother. Of course, as ordered by the censors, it was written in German. All three knew a little of the language from school. It was probably his first contact with his family since he left home. The only earlier information concerning their arrest was received by Bolek's mother in a secret message sent by an unknown patriot. From the preserved letters, it can be concluded that some time after they were transferred to separate barracks, they lost contact with Zdzisiek.

Camp life began at 4:30 am. The order of the day was rushing, pushing, beating and continuous work until dusk. The basic board consisted of three meals. In the morning they got only half a liter of, usually unsweetened, coffee, or rather boiled water with grain coffee or tea substitute. At noon, about 1 liter of soup made of potatoes, turnips, and a small amount of millet, rye flour and, "Avo" food extract. For dinner, about 300 grams of black bread was given, to which about 25 grams of sausage or margarine were added, or a tablespoon of marmalade or cheese. The evening portion of bread was to be saved and eaten also in the morning. Of course, they were so hungry that they ate it all at once. The nutritional value of these meals was low. The only relief was brought by parcels from the family. Perhaps one in five sent reached them. Families, suffering from basic food shortages, did what they could to help their loved ones. Mothers traveled around nearby villages buying meat and selling it in the cities. They put their lives at risk, but this was one of the few opportunities to earn money and get products for children's packages.

All inmates lost weight without exception in a short time. Shaved to bald skin, emaciated, shivering from malnutrition, cold and fear, they called themselves "Muslims".

Bolek was, among others, a writer and a medical assistant in Auschwitz. In 1942, while working on railway ramps, he experienced a nightmare that shook his faith in God. A new transport of prisoners was brought by a freight train. They had to travel for a long time, because among them were newborn babies. Drunken SS men made a bet with each other about which one would kill most newborn babies. They smashed their heads by hitting the soles of their shoes. The one who murdered eleven won. Bolek, unable to understand how God could allow such cruelty to happen, threw his pendant into the latrine. Later he regretted that he could have got a piece of sausage for it. In censored letters to his family, in a few words written solely in German, he asked about his brothers. Not getting any specific answers, he was angry at his parents. He did not know that, concerned with his mental health, they kept the death of his older brother, murdered in another concentration camp in May 1943, a secret from him.

During the liquidation of Auschwitz, Bolek was transported to a camp in Germany, probably Neungamme. The Allies liberated him a few kilometers from the sea, on the Death March. Hungry and exhausted after several days' walk without food or drink, he was found near a slain horse. He was immediately sent to hospital in order to save his life. He was in danger of dying after eating a carcass of the horse. After more than four years of starvation, any larger amount of food would endanger his life.

As soon as he regained some strength, he joined the Canadian army. After the war, he wondered what to do next. He realized that his mother and father were waiting for him at home, and that influenced his decision. He returned to Poland in 1946. He brought a Sahara motorcycle with him, which was immediately confiscated. Along the way, he was struck in his remaining seven teeth, as a punishment for a "delayed return to the country." As he once remarked, "what the Germans did not manage to knock out, the representatives of the new people's government finished."

Zdzisław Trawiński, ak.a. Zdziś

Zdzisław Trawiński

Zdzisław Trawiński died in Auschwitz on September 7, 1941 at the age of 17 years and two months, in unknown circumstances. His colleagues did not know his fate for a long time. And the desperate mother waited for a message from him for many months.

Romuald Hałaczkiewicz, a.k.a. Aldek

Romuald Hałaczkiewicz

Aldek had a brother in Auschwitz. Of course, this was not information known to the Germans. He was ten years older than him. He was caught in a street round—up and transported to the camp on August 15, 1940. As a former military officer, he probably had "false" papers. He never provided his real personal details. He had the camp number 2871. From time to time, he would add a note to a letter by Aldek, and sign it with the letter R.

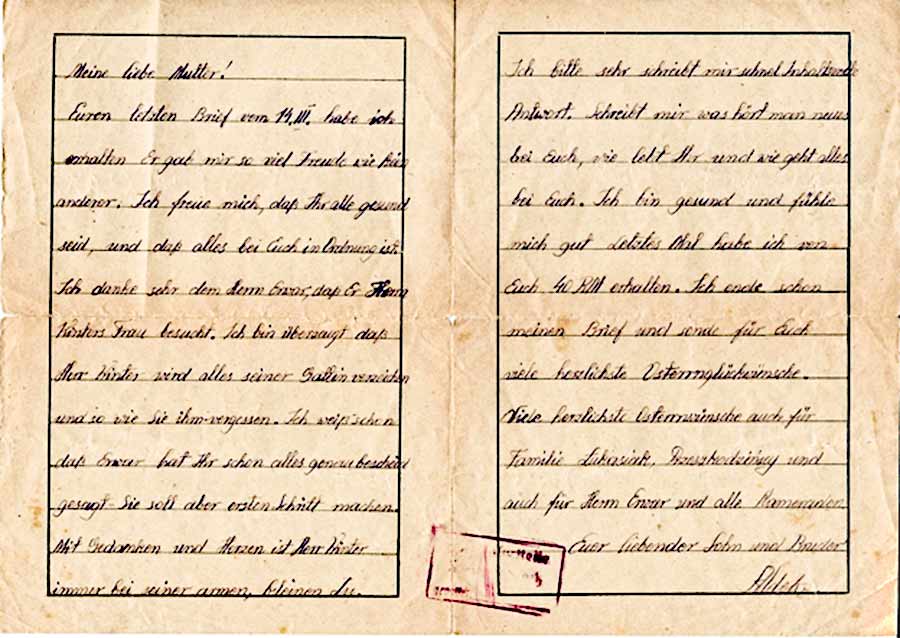

Aldek's life in the camp was similar to that of Bolek. He wrote to his family as often as he could. It gave him a substitute for normalcy. He had been half–orphaned for several years. The mother was no longer young. He knew that his letters, apart from the joy, caused her a lot of trouble. Neither she, nor the mothers of Bolek and Zdziś knew German. And it was the only language allowed by camp censorship. Together they traveled to a friend in Warsaw, who translated their letters. And then he wrote back on behalf of the mothers. As long as he was alive, he helped with correspondence. He died in the Warsaw Uprising.

One of Aldek's letters to his mother

In the camp, Aldek worked as a carpenter's assistant. It was his best "profession". Once, it saved his life. As he was standing in the line designated for death, he heard the SS-man asking, "Who is a carpenter?" Being only a helper, he still raised his hand. Once again, he miraculously saved himself. He was sick often and suffered from typhus. At some point he was so weak, that he found himself under the care of his friends in the camp hospital. They helped him regain his strength a little.

He was fond of animals, especially dogs. One day, an attack dog unleashed by an SS man did not attack him. It did not bite and tear. He attributed this to his love for pets. Shortly thereafter, camp dogs were replaced, in the belief that they were too gentle with the prisoners.

In Auschwitz, he survived two death sentences. Saving him from the third sentence, in the summer of 1943 his friends helped him and organized his transfer to the Neungamme concentration camp (prisoner number 18084). In his later memoirs, he wrote that the years of struggling to survive in Oświęcim taught him how to live in the camp, counting on nothing but the present, the moment being experienced. He was still a prisoner in Ravensbrück (No. 5558) and Sachsenhausen (No. 134985). He was freed by American troops after two weeks of marching in the Death March, 7 km from the town of Schwerin.

Looking at the photos of these three boys from Auschwitz, it is difficult to suppress the overwhelming terror. They were children. They came, at the age of sixteen, to a place created to destroy Poles. They spent all their youth fighting for mere one more minute of life. They were witnesses of genocide, not only of their people, but of humanity.

They've almost never mentioned the past. From time to time one could hear a short mention, story or confirmation of the information read about Auschwitz. They didn't like to plan. They lived day by day. They loved books. They spent every free moment reading.

They were minimalists. They both said that the proverbial table and chair would suffice for them. A few years after his wedding, Bolek gave his wedding rings to a friend. After all, he no longer needed them, and others would need them. When his wife dreamed of a ring for her twentieth wedding anniversary, she heard that "better not to think about such gifts. One day they will come, cut her finger and make 3 or 4 teeth out of her gold ring for Germans.”

One day, Aldek was assigned tables, chairs, and a wardrobe. He handed over the chairs and the table — his family only needed the wardrobe. Visiting his adult sons often, he would say that he could sleep anywhere, even on the floor, and all he needed was a newspaper for cover. In 1982, overcoming his reluctance against prisons and barbed wire, he stood in front of Białołȩka's prison and waited to visit his two sons interned by communists. The first visit was accompanied by reflections, probably unpleasant memories, shaking hands, and many smoked cigarettes. Next, he was getting used to the situation.

All their lives, they suffered from various health problems: stomach, digestive, and heart. Treatment did not help. Their health was destroyed and their psyche distorted.

Two of those who survived the camp nightmare regained their freedom at the age of twenty. But their bodies and souls ended up belonging to old men. Bolek never returned to Oświęcim. Aldek, half a year before his death, took some members of his family and — for the first time, probably sensing that the end was approaching — he crossed the gate of the former camp. It was also then, for the first and last time, that he said something about his experiences.

They tried to live like normal people. You could say that they worked more than they had to. Why? After all, not for money, which was of no great value to them. Probably that was how they kept busy and could forget about their past.

They started families, they had children. The suffering that was imprinted onto their souls had a profound effect on family life. They were not easy to get along with, neither for wives, nor for their children. Both were hypersensitive to noise. The house ought to have been kept quiet and peaceful. Bolek ordered the children to learn German. He knew the value of knowing foreign languages.

Not only they paid with their health. Aldek's children have never been vaccinated against tuberculosis, although this vaccine was mandatory. The tests that are done before vaccination have shown antibodies to tuberculosis in their bodies. It was a consequence of their father's contact with the disease in the camp.

They met occasionally after the war, but only with each other. Their families never knew one another in their lifetime. Bolesław Łukasiak suffered three heart attacks. He died at the age of 60 of lung cancer. Romuald Hałaczkiewicz also died of lung cancer, at the age of 65.

How what they have gone through will affect their grandchildren and great–grandchildren — the future will show. But it can be said that entire generations are already paying the price for what they have experienced. The horror they experienced can be seen on more than one face.

The materials and information used for the article come from the private collections of Jan Łukasiak and Zbigniew Hałaczkiewicz. The photos come from the collection of the museum in Oświęcim.